Activity

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleRemarks from the July 2018 global ideas summit: Peace Corps Connect to the Future see more

A host country perspective from Nepal. Remarks from the July 2020 global ideas summit: Peace Corps Connect to the Future.

By Kul Chandra Gautam

On July 18, 2020, National Peace Corps Association hosted Peace Corps Connect to the Future, a global ideas summit. NPCA invited three winners of the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award to share their perspectives. Here are remarks delivered by Kul Chandra Gautam — diplomat, public policy expert, and peace advocate — and former Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF.

I want to thank National Peace Corps Association for this opportunity to share my views on the future of the Peace Corps from the perspective of a host country, in my case, Nepal.

I have had five-decade long and happy association with the Peace Corps, since I was a 7th-grade student in the hills of Nepal. My wonderful Peace Corps teachers were instrumental in helping transform my life. And the 4,000+ Peace Corps Volunteers who have served in Nepal have contributed immensely to my country’s development.

I feel sad that because of the COVID pandemic the Peace Corps had to temporarily withdraw its Volunteers from all countries, including Nepal.

Today I join my fellow panelists from Guatemala and Kenya to address some weighty questions about the future of the Peace Corps from our perspective as global citizens, and that of our home countries.

Watch: Kul Chandra Gautam’s remarks at Peace Corps Connect to the Future

I deeply appreciate the soul-searching motivation for our reflection at this time of historic convulsion in the U.S., triggered by not only the COVID crisis but also the Black Lives Matter movement, and other crises facing America and the world.

Recent events have made all of us introspect deeply about combating systemic racism, and more broadly, promoting social justice, and ending the long legacy of racial, ethnic, religious, and gender-based disparities.

We find these phenomena not just in America, but in all countries where the Peace Corps serve.

Let me try to address these issues in a historic and holistic perspective.

During the past century, the United States has been the world’s greatest super-power. There have been three major sources of America’s super power status in the world — its economic prosperity, its military strength and its cultural vibrancy.

America has been the richest country in the world for nearly two centuries. The U.S. has only 4 percent of the world’s population, but 15 percent of the world’s GDP, and 30 percent of the world’s billionaires.

But we also find in America grotesque inequality, and great poverty in the midst of plenty.

It is the only rich country in the world without universal health coverage. In terms of people’s health & well-being, the U.S. is no longer a world leader.

The fact that the U.S. has more cases and deaths from COVID-19 than any other country in the world is a telling example of how America’s vast wealth fails to protect its people’s health.

The fact that the U.S. has more cases and deaths from COVID-19 than any other country in the world is a telling example of how America’s vast wealth fails to protect its people’s health.

America’s military strength has also been unparalleled in recent history.

Currently, the U.S. spends more than $700 billion annually on defense. That is close to 40 percent of the world’s military spending.

But this is increasingly becoming a burden without proportionate benefits for America. The trillions of dollars America spends on its military is increasingly becoming counter-productive. Instead of winning friends, America’s military might is turning people into enemies and even terrorists.

Look at what the trillions in military spending have produced in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, the Arab world, and even in Latin America — a wave of anti-Americanism.

I believe it is time now to reorient the American economy, drastically reduce military spending, and redirect it to end poverty, to reduce inequality, to provide health care and quality education for all, and to protect the earth from the climate crisis.

This is where America’s third strength comes into play.

America’s educational, scientific, and cultural vibrancy have earned the U.S. tremendous soft power in the world.

Forty percent of the world’s Nobel Prize winners have been Americans. More than 50 percent of the world’s Nobel laureates were trained in America. And 60 of the world’s 100 best universities are in America. The American scientific, technological, and cultural innovations have enveloped the whole world.

That is what gives America a positive soft power for the good of the world.

I consider the Peace Corps as one element of that benevolent American soft power.

I dare say that the less than half a billion dollars that America spends annually on the Peace Corps touches more ordinary people’s hearts, and helps nurture peace and friendship in the world than the many billions the U.S. spends on military aid to developing countries.

I recall that was precisely the vision of President John F Kennedy when he established the Peace Corps.

Kennedy envisioned the Peace Corps as an opportunity for young Americans to better understand the challenges of living in a developing country, to impart their knowledge and skills, and to help overcome poverty and underdevelopment.

Those are precisely the building blocks for peace and prosperity.

It is that spirit of solidarity and empathy that makes America, or Nepal, or any other country truly great.

To paraphrase the late Senator Teddy Kennedy, to make America Great Again: “It is better to send in the Peace Corps than the Marine Corps.”

I so wish that President Trump had been a Peace Corps volunteer. If he had the Peace Corps experience, he would have tried to make “America Great Again” by responding to the greatest challenges of our times — the COVID-19 pandemic, systemic racism, global poverty, and the climate crisis — in a completely different manner.

Our increasingly interconnected world demands global solidarity, not charity, to solve global problems that transcend national borders like the specter of war, terrorism, racism, climate change, and pandemics like COVID-19.

Let me now reflect on two questions that the NPCA asked us:

- How can the Peace Corps be a true partner with host countries in the new post-COVID world?

- And how must the Peace Corps change to be relevant for the 21st century?

Well, even before COVID-19 invaded and destabilized the world, we already had a universally agreed global agenda called the Sustainable Development Goals. Those goals, with dozens of specific and time-bound targets to be achieved by 2030, include ending extreme poverty, promoting prosperity with equity, protecting the environment and safeguarding people’s human rights.

They were endorsed by all countries of the world, including the United States, at the United Nations in 2015. The SDGs comprise a non-partisan agenda, so all of us can support them whether you are a Republican or Democrat or neither.

The Peace Corps Volunteers already promote these goals in their work as teachers, health promoters, agriculture extension workers, and a variety of other vocations.

What is needed now is to refine the skills of the Peace Corps Volunteers to ensure that their services are provided to truly empower local people and communities.

Like all other institutions are doing at this time, the Peace Corps too would benefit from an organizational soul searching to root out any trace of racism, gender discrimination, or a colonial mentality that may occasionally and inadvertently influence its work and mission.

I honestly believe that the Peace Corps can help transform the multiple crises facing the U.S. and the world into opportunity for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

I know from my own personal experience and observation that Peace Corps Volunteers can make a transformational impact on the lives of many ordinary people, and future leaders of host countries.

More than any other group of Americans, I believe that Returned Peace Corps Volunteers can instill a sense of a more enlightened America as part of, not apart from, a more just, peaceful and prosperous world.

Our increasingly interconnected world demands global solidarity, not charity, to solve global problems that transcend national borders like the specter of war, terrorism, racism, climate change, and pandemics like COVID-19.

I sincerely believe that the Peace Corps can be a great organization dedicated to promote such global solidarity at the people to people level.

Let us remember that solidarity, unlike charity, is a two-way street. The Peace Corps experience is just as important for the education and enlightenment of the Peace Corps Volunteers as it is for them to help their host communities.

More than any other group of Americans, I believe that Returned Peace Corps Volunteers can instill a sense of a more enlightened America as part of, not apart from, a more just, peaceful and prosperous world.

So, I hope and count on the Peace Corps to survive and thrive, and help build an enlightened post-COVID America and the world.

Thank you.

Kul Chandra Gautam is the 2018 recipient of the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award. He is a diplomat, public policy expert, peace advocate, and former Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleIn ‘Capote’s Women,’ Laurence Leamer writes a ‘Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era’ see more

Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era

By Laurence Leamer

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

“For years, Truman Capote had been proudly telling anyone within hearing that he was writing ‘the greatest novel of the age,’” begins Laurence Leamer’s latest biography, a tale of the literati and glitterati. Capote’s book “was about a group of the richest, most elegant women in the world. They were fictional, of course … but everyone knew these characters were based on his closest friends, the coterie of gorgeous, witty, and fabulously rich women he called his ‘swans.’”

Following publication of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood, Capote was a writer of renown, feted and admired. Among those he befriended and who took him into their confidence: Barbara “Babe” Paley, Gloria Guinness, Marella Agnelli, Slim Hayward, Pamela Churchill, C.Z. Guest, and Lee Radziwill (Jackie Kennedy’s sister). But Capote also suffered serious writer’s block, never completing his magnum opus, Answered Prayers, that he was sure would deserve a place beside Proust and Wharton. He only managed to complete and publish a few chapters in Esquire in 1975. When Capote’s authorized biographer, Gerald Clark, read the excerpt pre-publication, he was alarmed that the women would recognized themselves immediately. “Naaah, they’re too dumb,” Capote told Clark. “They won’t know who they are.”

Laurence Leamer has written here a story of betrayal. And it’s a story of failure — a swan song not at all like the one Capote intended — by a great American writer who found “nothing in love was too bizarre for his scrutiny.”

Bestselling author Leamer has indeed written here a story of betrayal. And it’s a story of failure — a swan song not at all like the one Capote intended — by a great American writer who found “nothing in love was too bizarre for his scrutiny.”

Leamer himself served as a Volunteer in Nepal 1965–67, “where I had a remote placement two days walk from a road,” as he told Peace Corps Worldwide. Leamer went on to cover the war in Bangladesh for Harper’s, and his journalism has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, New York, Playboy, and elsewhere. He drew on his knowledge of Nepal for Ascent: The Spiritual and Physical Quest of Legendary Mountaineer Willi Unsoeld. But he has no doubt become best known for tales of the wealthy and powerful in book form that include Make-Believe: The Life of Nancy and Ronald Reagan; a trilogy on the Kennedys; Fantastic, a biography of Arnold Schwarzenegger; and Madness Under the Royal Palms, telling the secrets and scandals of South Florida. A deeper dive into one of that area’s most famous denizens appeared in 2019 — Mar-a-Lago: Inside the Gates of Power at Donald Trump’s Presidential Palace — a book, Leamer says, “written with all I know about Palm Beach after living there for a quarter-century and all I know about politics and human personality after a lifetime as a writer.”

Over the years, Leamer has also turned his sights on projects that have had a profound effect on the wider world. The Lynching: The Epic Courtroom Battle That Brought Down the Klan, earned a place on must-reads lists by Oprah Winfrey and Tavis Smiley. For The Price of Justice, he went undercover to work in a West Virginia coal mine and told the story of two lawyers’ struggle against Don Blankenship, “the most powerful coal baron in American history. Blankenship was indicted and sent to prison,” Leamer notes. “People in West Virginia will tell you it would not have happened without The Price of Justice.”

This review appears in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of WorldView magazine.

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleUpdates from the Peace Corps community — across the country and around the world see more

News and updates from the Peace Corps community — across the country, around the world, and spanning generations of returned Volunteers and staff.

By Peter V. Deekle (Iran 1968–70)

Jamie Hopkins, who served as a Volunteer in Ukraine 1996–98, leads the Eagan Community Foundation in Minnesota and spearheaded a three-day film festival in support of Ukraine in April and May. Krista Kinnard (Ecuador 2010–21) has been named a 2022 finalist for the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medal, for her work spearheading new, efficiency-boosting and cost effective technologies for the Department of Labor (DOL). Rob Schmitz (China 1996–98) had a stint as guest host of NPR’s All Things Considered radio show. Tommy Vinh Bui (Kazakhstan 2011) was nominated as Local Hero of the Week for his good deeds and unwavering commitment to serving his Los Angeles community during the COVID-19 pandemic. We share news about more awards, medals, and director roles.

Have news to share with the Peace Corps community? Let us know.

CHINA

Rob Schmitz (1996–98) became a guest host of NPR’s All Things Considered radio show in late April. As NPR’s Central Europe Correspondent, Schmitz covers the human stories of a vast region, such as Germany’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic, rise of right-wing nationalist politics in Poland and creeping Chinese government influence inside the Czech Republic. Before reporting on Europe, Schmitz worked as a foreign correspondent covering China and its economic rise and increasing global influence for a decade. He also authored the award-winning book Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along a Shanghai Road which profiles the lives of individuals residing along a single street in the heart of Shanghai. During his first week as guest host, Schmitz talked with a Shanghai resident who discussed her experience with Shanghai’s zero-COVID strategy and the recent pandemic restrictions. Listen here.

COSTA RICA

Lane Bunkers (1989–91) took on responsibilities as of Peace Corps Country Director of Costa Rica in March. Bunkers steps into this new position a year before Peace Corps Costa Rica’s 60th anniversary and amidst the first wave of Volunteers returning to service overseas. In his director’s welcome, Bunkers wrote, “In Costa Rica, the pandemic impacted the social, economic, and political environment, as it did throughout the world. The country’s recovery will take time, and Peace Corps is well-positioned to support the communities where our Volunteers serve.” He brings an extensive career in leadership and international development, including three years serving as Peace Corps program and training officer in Romania and in the Eastern Caribbean. Prior to his new role, Bunkers worked for Catholic Relief Services for more than two decades. While there he oversaw a $25 million annual budget invested in initiatives ranging from water and food aid for drought-stricken regions to improving educational outcomes for malnourished children.

ECUADOR

Krista Kinnard (2010–2012) was named a 2022 finalist for the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medal, for her work spearheading new, efficiency-boosting and cost effective technologies for the Department of Labor (DOL). Since starting her role as DOL’s chief of emerging technologies in 2021, Kinnard has focused on ways to use artificial intelligence, automation, and machine learning to reduce the time employees spend on repetitive tasks. She also collaborated with the department to establish a technology incubator, inviting DOL staff to propose ideas that could benefit agencies and the public. Before working at DOL, Kinnard was the director of the U.S. General Service Administration’s Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence. Her data-driven expertise sharpened during her Peace Corps service where she was able to apply her quantitative skills to real-world problems. Afterward, she pursued a master’s in data analytics and public policy before building AI and machine learning tools for federal clients as a data scientist at IBM.

GUYANA

Dr. Nadine Rogers, who serves as country director for Peace Corps Guyana, is a 2022 recipient of the Global Achievement Award from the Johns Hopkins University Alumni Association. “This well-deserved and extraordinary accomplishment highlights her incredible contributions in the international arena," says Peace Corps CEO Carol Spahn. Dr. Rogers has almost 30 years of experience in management, health policy implementation, science administration, and education and communications across the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. She has previously served as a foreign service officer at the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator under the U.S. State Department, and for 10 years she worked at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, handling scientific review of multi-million dollar research grant applications focused on HIV/AIDS prevention and services in populations at risk-for or addicted to drugs, both domestically and internationally. She has served the U.S. government across the globe, including in Vietnam, Cambodia, Uganda, Ethiopia, South Africa, Zambia, and in the Caribbean.

KAZAKHSTAN

Tommy Vinh Bui (2011) was nominated as Local Hero of the Week in April for his good deeds and unwavering commitment to serving his community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bui was working as a Los Angeles Teen and Adult Services Librarian when the pandemic shut down libraries. With a love for his community and a penchant for service, he sprang into action seeking ways to help such as donating blood to the Red Cross to help with the blood shortage; delivering convalescent plasma to hospitals around and outside of Los Angeles; assisting Project Roomkey — an initiative started by the California Department of Social Services, providing shelter for unhoused people recovering from or exposed to COVID-19 — in its efforts to help vulnerable people get off the streets and find resources. As part of the last cohort to serve in Kazakhstan, Bui’s Peace Corps service began in March 2011. He served as a community development and education Volunteer until he was evacuated in November of that same year and credits his experience as a major contributor to his personal and professional growth.

KENYA

Josh Josa (2010–12) is a 2022 finalist for the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medal, an honor reserved for the most innovative and exceptional federal workers. As a member of the Deaf community and a first-generation Hungarian-American, Josa’s commitment to equity and inclusion in education is fueled by his first-hand experience with the stigma, barriers, and lack of resources students with disabilities face in school. While working as an inclusive education specialist at the U.S. Agency for International Development, Josa has sought to design and implement programs delivering quality, equitable, and inclusive education to all children and youth. He has worked tirelessly to advance educational inclusivity for students with disabilities, whether it be in Morocco, Kenya, or the United States.

LESOTHO

Travis Wohlrab (2013–15) received the NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal for developing a livestream production capability and supporting agency communications programs. This medal recognizes those who significantly improve NASA’s day-to-day operations. Wohlrab is the engagement officer at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he has worked since the end of his Peace Corps service. During the onset of COVID-19, Wohlrab used his video production expertise to produce livestream events — such as Town Halls and public outreach events — which were crucial to helping the center continue to disseminate information and operate as it had before the pandemic.

NEPAL

Lowell Hurst (1976–78) received the 2022 Lifetime Achievement Award, along with his wife Wendy, from the Pajaro Valley Chamber Of Commerce and Agriculture. Hurst has dedicated his life to education, public service, and volunteerism starting with his Peace Corps service — followed by the more than three decades he spent teaching science and horticulture at Watsonville High School. In 1989, he was elected to the Watsonville City Council, served on the body for three stints over three decades, and served three mayoral terms, retiring from the political arena after his final term.

NICARAGUA

Heather Laird was appointed the new medical director of Volunteers in Medicine Clinic of the Cascades (VIM) in April. She first got involved with VIM by serving as a volunteer nurse practitioner in 2013, while working at her full-time job in telemedicine. Laird shifted away from telemedicine to work with patients in person at Mosaic Medical — a community-founded health center focused on making high-quality healthcare available to Central Oregonians, regardless of life circumstances. Inspired by her Peace Corps experience, which allowed her to learn technical skills that would help her community, Laird pursued a master’s in environmental and occupational health sciences at University of Washington before attending University of California, San Francisco, and obtaining a degree to become an adult nurse practitioner. “I am looking forward to harnessing my experience and education to help the underserved in Central Oregon through my role at Volunteers in Medicine,” Laird said.

UKRAINE

In April and May, Jamie Hopkins (1996–98), who serves as executive director of the Eagan Community Foundation, spearheaded the Twin Cities Ukrainian Film Series. “It’s important for me to tell people about Ukraine,” Hopkins said. “I’ve been trying to do that for 25 years, and for the first time people are really anxious to learn.” Together with the Emagine Theaters, the foundation put on a three-day film fundraiser to benefit a variety of needs in Ukraine, including funding for filmmakers documenting the current war and community foundations in the areas hardest hit. “I want to make sure that opportunity exists today to do that (make Ukrainian films) in the future,” Hopkins said. As a Peace Corps Volunteer, Hopkins served as a teacher trainer in the town of Ukrainka in the Kyiv Region — something she describes as “most rewarding experience of my life.” Hopkins has served as the Eagan Community Foundation’s executive director since 2016. She originally joined the foundation as a board member in 2013.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAn excerpt from Ambika Joshee’s candid memoir, The Life of a Nepali Village Boy see more

For 30 years Ambika Joshee worked for the Peace Corps in Nepal. His memoir, The Life of a Nepali Village Boy, is a candid account of a country being transformed — and traces a personal quest for knowledge, justice, and understanding. Here is an excerpt.

An Audience with the King

By Ambika Mohan Joshee

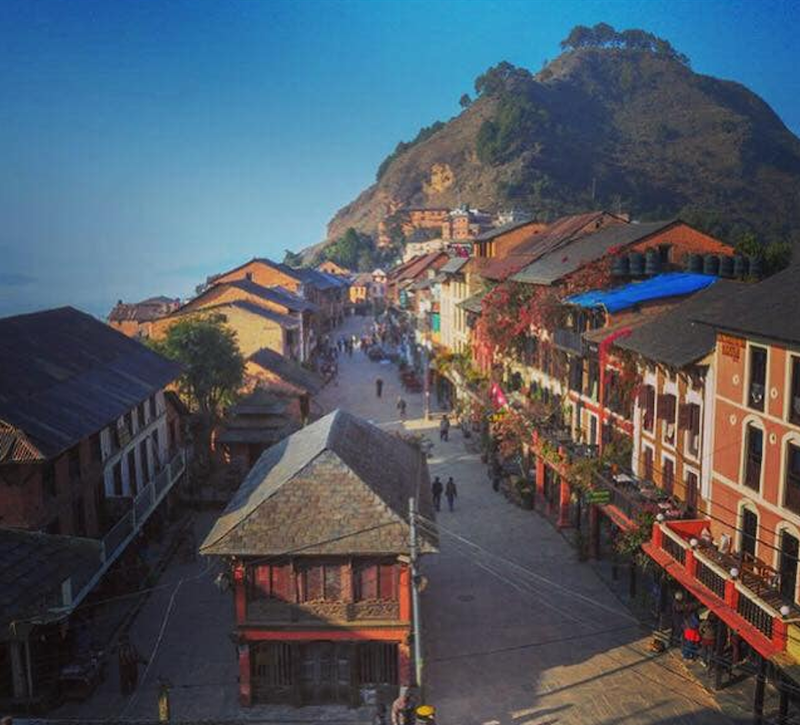

Bandipur is seven kilometers south of Dumre Bazar, which is on the Kathmandu-Pokhara highway. It is a small hilltop settlement with a population of about 16,000. About 1,030 meters above sea level, on a saddle of the Mahabharat range, it is a beautiful town with old Newari architecture. Houses have slate roofs, and the bazaar has been paved with slate. Motorized vehicles are not allowed into the town center. It is a living museum of Newari culture. The Bandipur bazaar used to be a trade center supplying merchandise to the villages of Tanahu, Lamjung, Mustang, and Manang, and the Kaski, Palpa, and Shyangja districts of western Nepal. The massive flood of 1954 forced many people from those districts, and businessmen from Bandipur settled in the flatlands of Chitawan.

The government’s transfer of the district center from Bandipur to Damauli played a vital role in encouraging the migration of Bandipures to Dumre and Damauli. The then prime minister, Surya Bahadur Thapa, took political revenge on the Bandipures by transferring the district headquarters from Bandipur to Damauli. Another blow was in building the Prithvi Highway, not through Bandipur but instead around the hill below, making it a deserted town.

Bandipur in the 1970s — a town being abandoned as it faced economic hardship and the aftermath of political revenge. Photo courtesy Ambika Joshee

Now the town is slowly developing as a hub for nearby tourist spots and as an education center with a college, two high schools, one middle school, and several elementary schools. Small agricultural and other home-based industries have begun popping up, improving the economy of the area.

While we were performing for the king, someone came onstage and told us we were being rounded up by the army — just like prisoners.

If I remember correctly, I was in sixth grade. It was just before the beginning of the Panchayat system in 1961. King Mahendra was making tours around the country. The rumor came that the king planned a visit to Bandipur; youths and schoolteachers planned a drama to show him. I was an actor in the drama — about the Revolution of 2007 BS (1951 AD) — and we used firecrackers to replicate gunfire. While we were performing for the king, someone came onstage and told us we were being rounded up by the army — just like prisoners. We had no idea that we had to ask their permission to use firecrackers because we were showing the drama to the king. The army commander came onstage and asked us many questions that we could not answer. He then realized our ignorance and let us continue. It was a new and strange experience for us.

Bandipures were and still are very much interested in and enthusiastic about education. The affluent and elite often sent their male offspring to Kathmandu; others had to depend on whatever was available there. Existing facilities were very crowded, the building dilapidated. The people realized the need for new facilities.

Hira Lall and Shyam Krishna Pradhan donated a plot of land at the foot of Gurungche danda, and construction funds were collected from local residents. The managing committee requested the king lay the foundation stone while in Bandipur for his visit.

Bandipur today — restored as a place of architectural beauty after decades of economic hardship. Photo courtesy Ambika Joshee

Around noon, the king went to the new school ground with his entourage. A fine stage was made. The place was decorated with flowers, and colored triangular flags made of paper were attached to strings. The whole town gathered. The kings were seen as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and people had the belief that one look at the king would open their door to heaven.

My hands started shaking, and I was having a problem even getting the scarf around his neck.

We had a small Nepal Scouts team at the school. The scout committee assigned me to tie a scout scarf around the king’s neck on the stage. I had never been in front of any dignitaries before. I was sweating even before I approached the stage. I had the scout scarf in my hand, and I presented the scout salute as soon as I climbed the small ladder to the stage. Then I slowly marched forward and stopped when I was just about a foot or two from the king. Everything was going as I had been taught by my teachers until I started tying the scout knot. My hands started shaking, and I was having a problem even getting the scarf around his neck. I spent about five minutes trying to make the knots, but I had no luck. He was smiling and kept quiet. He did not say a single word. He was just looking at me, which also made me nervous. After about five minutes, when the aide-de-camp general saw that I had not succeeded in tying the knot, he told me, “Just leave it. It is all right. You don’t have to tie the knot.”

Adapted from The Life of a Nepali Village Boy by Ambika Mohan Joshee © 2021, published by Peace Corps Writers.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAsian American and Pacific Islander leaders have a conversation on Peace Corps, race, and more. see more

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity. A conversation convened as Part of Peace Corps Connect 2021.

Image by Shutterstock

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are currently the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S., but the story of the U.S. AAPI population dates back decades — and is often overlooked. As the community faces an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes and the widening income gap between the wealthiest and poorest, their role in politics and social justice is increasingly important.

The AAPI story is also complex — 22 million Asian Americans trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent, each with unique histories, cultures, languages, and other characteristics. Their unique perspectives and experiences have also played critical roles in American diplomacy across the globe.

For Peace Corps Connect 2021, we brought together three women who have served or are serving as political leaders to talk with returned Volunteer Mary Owen-Thomas. Below are edited excerpts from their conversation on September 23, 2021. Watch the entire conversation here.

Rep. Grace Meng

Member, U.S. House of Representatives, representing New York’s sixth district — the first Asian American to represent her state in Congress.

Julia Chang Bloch

Former U.S. ambassador to Nepal — the first Asian American to serve as a U.S. ambassador to any country. Founder and president of U.S.-China Education Trust. Peace Corps Volunteer in Malaysia (1964–66).

Elaine Chao

Former Director of the Peace Corps (1991–92). Former Secretary of Labor — the first Asian American to hold a cabinet-level post. Former Secretary of Transportation.

Moderated by Mary Owen-Thomas

Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines (2005–06) and secretary of the NPCA Board of Directors.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. This is not a recent story — and it’s often overlooked. I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines, and I happen to be Filipino American.

During my service, people would say, “Oh, we didn’t get a real American.” I used to think, I’m from Detroit! I’m curious if you’ve ever encountered this in your international work.

Julia Chang Bloch: With the Peace Corps, I was sent to Borneo, in Sabah, Malaysia. I was a teacher at a Chinese middle school that had been a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. The day I arrived on campus, there was a hush in the audience. I don’t speak Cantonese, but I could understand a bit, and I heard: “Why did they send us a Japanese?” I did not know the school had been a prisoner of war camp. They introduced me. I said a few words in English, then a few words in Mandarin. And they said, “Oh, she’s Chinese.”

I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised me I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.”

In Nepal, where I was ambassador, when I arrived and met the Chinese ambassador, he said, “Ah, China now has two of us.” I said, “There’s a twist, however. I am a Chinese American.” He laughed, and we became friends thereafter. On one of my trips into the western regions, where there were a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers and very poor villages, I was welcomed lavishly by one village. I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.” He said to her, “There she is.” “Oh, no,” she said. “She is not the American ambassador. She’s Nepali.”

Those are examples of why AAPI representation in foreign affairs is important. We should look like America, abroad, in our embassies. We can show the world that we are in fact diverse and rich culturally.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Secretary Chao, at the Labor Department you launched the annual Asian Pacific American Federal Career Advancement Summit, and the annual Opportunity Conference. The department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics began reporting the employment data on Asians in America as a distinct category — a first. You ensured that labor law materials were translated into multiple languages, including Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean. Talk about how those came about.

Elaine Chao: Many of us have commented about the lack of diversity in top management, even in the federal government. There seems to be a bamboo ceiling — Asian Americans not breaking into the executive suite. I started the Asian Pacific American Federal Advancement Forum to equip, train, prepare Asian Americans to go into senior ranks of the federal government.

The Opportunity Conference was for communities of color, people who have traditionally been underserved in the federal government, in the federal procurement areas. Thirdly, in 2003 we finally broke out Asians and Asian American unemployment numbers for the first time. That’s how we know Asian Americans have the lowest unemployment rate. Labor laws are complicated, so we started a process translating labor laws into Asian, East Asian, and South Asian languages, so that people would understand their obligations to protect the workforce.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized.

Grace Meng: I am not a Peace Corps Volunteer, but I am honored to be here. My former legislative director, Helen Beaudreau (Georgia 2004–06, The Philippines 2010–11), is a twice-Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. I am incredibly grateful for all of your service to our country, and literally representing America at every corner of the globe.

I was born and raised here. This past year and a half has been a wake-up call for our community. Asian Americans have been discriminated against long before — starting with legislation that Congress passed, like the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Japanese American citizens being put in internment camps. We have too often been viewed as outsiders or foreigners.

I live in Queens, New York, one of the most diverse counties in the country, and still have experiences where people ask where I learned to speak English so well, or where am I really from. When I was elected to the state legislature, some of us were watching the news — a group of people fighting. One colleague turned to me and said, “Well, Grace knows karate, I’m sure she can save us.”

By the way, I don’t know karate.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized. I didn’t necessarily come to Congress just to represent the AAPI community. But there are many tables we’re sitting at, where if we did not speak up for the AAPI community, no one else would.

At the root of hate

Julia Chang Bloch: I believe at the root of this anti-Asian hate is ignorance about the AAPI community. It’s a consequence of the exclusion, erasure, and invisibility of Asian Americans in K–12 school curricula. We need to increase education about the history of anti-Asian racism, as well as contributions of Asian Americans to society. Representative Meng, you should talk about your legislation.

Grace Meng: My first legislation, when I was in the state legislature, was to work on getting Lunar New Year and Eid on public school holidays in New York City. When I was in elementary school, we got off for Rosh Hashanah; don’t get me wrong, I was thrilled to have two days off. But I had to go to school on Lunar New Year. I thought that was incredibly unfair in a city like New York. Ultimately, it changed through our mayor.

In textbooks, maybe there was a paragraph or two about how Asian Americans fit into our American history. There wasn’t much. One of my goals is to ensure that Asian American students recognize in ways that I didn’t that they are just as American as anyone else. I used to be embarrassed about my parents working in a restaurant, or that they didn’t dress like the other parents.

Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Julia Chang Bloch: I wonder about data collection. We’re categorized as AAPI — all lumped together. And data, I believe, is collected that way at the national, state, and local levels. Is there some way to disaggregate this data collection and recognize the differences?

Elaine Chao: A very good question. Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Two obstacles stand in the way. One is resources. Unless there is thinking about how to do this in a systemic, long-term fashion, getting resources is difficult; these are expensive undertakings. Two, there’s sometimes political resistance. Pew Charitable Trust, in 2012, did an excellent job: the first major demographic study on the Asian American population in the United States. But we’re coming up on 10 years. That needs to be revisited.

Role models vs. stereotypes

Elaine Chao: Ambassador Julia Chang Bloch and Pauline Tsui started the organization Chinese American Women. I remember coming to Washington as a young pup and seeing these fantastic, empowering women. They blazed so many trails. They gave voice to Asian American women.

I come from a family of six daughters. I credit my parents for empowering their daughters from an early age. They told us that if you work hard, you can do whatever you want to do. We’ve got to offer more inspiration and be more supportive.

Julia Chang Bloch: Pauline Tsui has unfortunately passed away. She had a foundation, which gave us support to establish a series on Asian women trailblazers. Our inaugural program featured Secretary Chao and Representative Judy Chu, because it was about government and service. Our next one is focused on higher education. Our third will be on journalism.

I want, however, to leave you with this thought. The Page Act of 1875 barred women from China, Japan, and all other Asian countries from entering the United States. Why? Because the thought was they brought prostitution. The stereotyping of Asian women has been insidious and harmful to our achieving positions of authority and leadership. That’s led also to horrible stereotypes that have exoticized and sexualized Asian women. Think about the women who were killed in Atlanta.

That intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something we need to continue to combat.

Grace Meng: There was the automatic assumption, in the beginning, that they were sex workers — these stereotypes were being circulated. I had the opportunity with some of my colleagues to go to Atlanta and meet some of the victims’ families, to hear their stories. That really gave me a wake-up call. I talked about my own upbringing for the first time.

I remember when my parents, who worked in a restaurant, came to school, and they were dressed like they worked in a restaurant. I was too embarrassed to say hello. Being in Atlanta, talking to those families, made me realize the sacrifices that Asian American women at all levels have faced so that we could have the opportunity to be educated here, to get jobs, to serve our country. And that intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something that we need to continue to combat.

Julia Chang Bloch: We’ve talked about the sexualized, exoticized, and objectified stereotype — the Suzie Wongs and the Madame Butterflys. However, those of us here today, I think would fall into another category: the “dragon lady” stereotype. Any Asian woman of authority is classified as a dragon lady — a derogatory stereotype. Women who are powerful, but also deceitful and manipulating and cruel. Today it’s women who are authoritative and powerful.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Growing up, I was sort of embarrassed of my mom’s thick Filipino accent; she was embarrassed of it, too. I was embarrassed of the food she would send me to school with — rice, mung beans, egg rolls, and fish sauce. And people would ask, “What is that?” Talk about how your self-identity has evolved — and how you view family.

You do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Grace Meng: I don’t know if it’s related to being Asian, but I was super shy as a child. And there weren’t a lot of Asians around me. I was the type who would tremble if a teacher called on me; I would try to disappear into the walls. When I meet people who knew me in school, they say, “I cannot believe you’re in politics.”

What gave me strength was getting involved in the community, seeing as a student in high school, college, and law school that I could help people around me. After law school I started a nonprofit with some friends. We had senior citizens come in with their mail once a week, and we would help them read it. It wasn’t rocket science at all.

I tell that story to young people, because you do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Julia Chang Bloch: At some point, in most Asian American young people’s lives, you ask yourself whether you are Chinese or American — or, Mary, in your case, whether you’re Filipino or American.

I asked myself that question one year after I arrived in San Francisco from China. I was 10. I entered a forensic contest to speak on being a marginalized citizen. I won the contest, but I didn’t have the answer. At university, I found Chinese student associations I thought would be my answer to my identity. But I did not find myself fitting into the American-born Chinese groups — ABCs — or those fresh off the boat, FOBs. Increasingly, my circle of friends became predominantly white. I perceived the powerlessness of the Chinese in America. I realized that only mainstreaming would make me be able to make a difference in America.

After graduation, I joined the Peace Corps, to pursue my roots and to make a difference in the world. Teaching English at a Chinese middle school gave me the opportunity to find out once and for all whether I was Chinese or American. I think you know the answer.

My ambassadorship made me a Chinese American who straddles the East and the West. And having been a Peace Corps Volunteer, I have always believed that it was my obligation to bring China home to America, and vice versa. And that’s what I’ve been doing with the U.S.-China Education Trust since 1998.

We should say representation matters. Peace Corps matters, too.

WATCH THE ENTIRE CONVERSATION here: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity

These edited remarks appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022. -

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleFrom being taught by Peace Corps Volunteers to becoming a Volunteer see more

In Moldova, my work partners and our host family weren’t expecting someone like me. Instead of being young and white, I was older and Asian. And born near Mount Everest.

By Champa Jarmul

When I was a girl growing up in Nepal, two of my teachers were Peace Corps Volunteers. After I became a teacher myself, I attended a training workshop with another Volunteer. Most important to me was the PCV who taught at our school a few years later. David and I fell in love and got married.

More than 35 years later, after our two sons had grown, we signed up to serve as Volunteers together in Moldova. David worked in the local library and I taught English at a school. I wasn’t sure I would be a good Volunteer, but I was ready to be open-hearted and nonjudgmental, and to accept all of the challenges.

Moldovan students with their Peace Corps teacher, Champa Jarmul, at far end of table. Photo courtesy of Champa and David Jarmul

My work partners and our host family weren’t expecting someone like me. Instead of being young and white, I was older and Asian. Few Moldovans had ever heard of Nepal. When I told them I was born near Mount Everest, they were amazed. But they weren’t sure I was a “real American.” As we lived and worked together, though, they came to know me.

When I told them I was born near Mount Everest, they were amazed. But they weren’t sure I was a “real American.”

We cooked each other our traditional foods — curried chicken and rice from Nepal, stuffed cabbage and pork from Moldova, and an American apple pie. We shared photos of our grandchildren. We celebrated each others’ birthdays and holidays, including a big turkey dinner on Thanksgiving.

Peace Corps family: Champa and David Jarmul with their grandchildren. Photo courtesy of Champa and David Jarmul

Our Peace Corps group included Americans born in other countries as well, from Panamá, Colombia, the Philippines, Myanmar, and Vietnam. We had American-born Volunteers of different ethnicities, ages, and sexual orientations. Many of us were not what Moldovans expected a Volunteer would look like. Together, we showed them that “American” includes many kinds of people.

As Peace Corps looks to its future, its Volunteers need to fully reflect our country’s diversity. We are the faces of America. Our stories are America’s stories.

READ MORE: “Returning to Serve as a Peace Corps Volunteer a Second Time — 35 years Later” by David Jarmul

-

Communications Intern posted an articleEvacuation, some Peace Corps history, and #apush4peace see more

Evacuation, some Peace Corps history, and #apush4peace

When Coronavirus Unmapped the Peace Corps' Journey

Jeffrey Aubuchon (92252 Press)Reviewed by Jake Arce and Steven Boyd Saum

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the unprecedented global evacuation of Peace Corps Volunteers. Jeffrey Aubuchon brings together stories of some evacuees chronicled in WorldView: Chelsea Bajek, who was working with a women’s group in Vanuatu; Jim Damico, evacuated from teaching in Nepal; Benjamin Rietmann, yanked from his work with farmers and young entrepreneurs in Dominican Republic; and Stacie Scott, who left behind the community she was serving as a health volunteer in Mozambique.

Aubuchon follows in greater depth two Southern California high school sweethearts, Jacqueline Moore-DesLauriers and Dylan Thompson, who served together in Morocco. In Sefrou (pop. 80,000), on the outskirts of Fez, they taught English classes and hosted a STEMpowerment workshop for girls at the local dar chabab (youth center). They established a girls’ volleyball team that played its first game on March 5. Ten days later, Peace Corps announced its global evacuation.

“Never in the last 40 years has the Association’s mission been more vital.”

The book also serves up some context for 2020 — when each week seemed like a year unto itself. And National Peace Corps Association gets more than a passing nod — particularly its crucial work advocating for evacuated Volunteers, which helped secure additional benefits for them and $88 million in supplemental funding for Peace Corps. “Never in the last 40 years has the Association’s mission been more vital,” Aubuchon writes. “Indeed, on March 16, 2020, NPCA President Glenn Blumhorst released a statement not only voicing support for all of the EPCVs, but also outlining a national plan to coordinate support for these evacuees among the Peace Corps, the NPCA, and the RPCV community itself.”

Aubuchon served as a Volunteer in Morocco 2007–09. “I walked my own Peace Corps journey in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the Casablanca bombings of 2003,” he writes. He applied for and received grant funding to help build four libraries. In fall 2019, he was teaching a course in Advanced Placement U.S. History at a high school in central Massachusetts. A lesson in Cold War history led students to do more than merely talk about global problems; they founded a youth venture — and began raising funds to support Peace Corps Volunteers’ projects. Taking the acronym for the class, APUSH, they hasthtagged their effort #apush4peace. They convinced community members to put up $1,000 in seed funding — and then, through fundraising, more than tripled that, “allowing them to help a PCV in Zambia build a hospital clinic ward and help another build a library in Mozambique.”

Paama Custom Arts Festival: Traditional basket weaving on Vanuatu. Chelsea Bajek worked with these women to launch a business project. Photo by Chelsea Bajek

One of those APUSH students, Olivia Wells, takes over the closing chapter of the book. She observes: “Few people know that there are ways to help educate adolescents in Eswatini (Swaziland) about HIV/AIDS, or to help local farmers in Malawi construct an irrigation system to decrease water erosion on their farmland.”

This is a project that’s meant to give back; one dollar from each copy sold goes to Kiva.org to support microfinance projects, and another dollar goes to support National Peace Corps Association.

As for the stories of the Volunteers who were evacuated: Those journeys continue beyond the pages of the book. For example, Jim Damico, a three-time Volunteer, didn’t wait for Peace Corps to return to Nepal. He went back on his own in January 2021 and has been mentoring teachers. Chelsea Bajek, who was serving in Vanuatu, had successfully applied for a Peace Corps Partnership Program grant to purchase equipment and materials for skill-building workshops at the Paama Women’s Handicraft Center. But those funds were cut off when Bajek was evacuated. Thanks to crowdsourcing and NPCA’s Community Fund, in 2021 that project was fully funded and will, Bajek reports, increase opportunities for women’s economic development and empowerment.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleIn the 1970s he served in Nepal. More than three decades later, he returned to serve in Moldova. see more

In the 1970s, David Jarmul served as a Volunteer in Nepal. More than three decades later, he and his wife, Champa, returned to serve in Moldova. Lessons and advice for experienced would-be Volunteers — and how they can make an impact.

By David Jarmul

Photos courtesy David Jarmul

What’s it like to serve as a Peace Corps Volunteer in your twenties and then again decades later? David Jarmul takes a deep dive into that topic his recent book, Not Exactly Retired: A Life-Changing Journey on the Road and in the Peace Corps. He “teases out a striking contrast between his service in Nepal 35 years ago and in Moldova in the age of Trump,” says Marco Werman, host of The World on public radio.

Here’s a taste of Jarmul’s book — shaped by a particular place and time, before the global evacuation of Volunteers in March 2020. But as Peace Corps continues recruiting Volunteers, with hopes of them returning to the field in the second half of 2021, there’s plenty to chew on here.

David Jarmul served in Moldova from 2016 to 2018 with his wife, Champa, whom he met during his initial Peace Corps stint in Nepal, where he served from 1977 to 1979. David and Champa live in Durham, North Carolina, where David worked previously as the head of news and communications for Duke University.

Not Exactly Retired is published by the Peace Corps Writers imprint. Learn more and follow Jarmul’s blog at notexactlyretiredbook.com.

Moldova Bound

Before Champa and I joined the Peace Corps at the age of 63, we knew most of the other Volunteers would be younger than our two sons. We were surprised to discover that one in four of those in our M31 group were fifty or older. Worldwide, Americans over the age of 50 comprised about 7 percent of Peace Corps Volunteers then. With better medical facilities and programs in fields such as business development, Moldova attracted people with lots of real-world experience, particularly with our group.

Whatever their reasons for choosing Moldova, our fellow older Volunteers were impressive. They’d worked as professors, attorneys, IT managers, nonprofit leaders, teachers, city administrators, and management consultants. Coming from Harlem to California, they were single, widowed, divorced, or married. Like the other Volunteers, they were also diverse ethnically, reflecting the country we represented.

Arts in Class: Peace Corps Volunteer Champa Jarmul and her students in Moldova

We differed from our younger counterparts in some ways. Champa and I weren’t the only ones who found it challenging to learn Romanian. We ran slower at group soccer games if we played at all. When our younger friends went to get tattoos, they knew better than to invite the two of us, although some of the older volunteers joined in. Some of our younger peers also partied harder than us and made surprising cultural references. When I was in the Peace Corps office one day, a Carole King song started playing, and the young woman next to me said, “Hey, it’s that song from the Gilmore Girls!” On the other hand, they were usually polite when we made our own references to people and events from before they were born, so it tended to even out.

There were advantages to being an older Volunteer in Moldova, just as there were in other Peace Corps countries. People in our host communities generally showed respect towards people our age. Having children and grandchildren provided us with an instant bond with older members of those communities, including the folks running the schools and other institutions. Our experience enhanced our credibility in our workplaces. My future colleagues wasted little time in checking me out online, so they knew I’d held positions of responsibility back home. This led them to treat me more like a peer or mentor even before I’d proven myself. As older Volunteers, we could also share our longstanding hobbies, which included art and gardening for Champa.

The medical clearance process was especially tedious for older applicants, with our own taking several months even though we were in good health. Given all of the medical problems that arose with some of our older friends, I understood why the Peace Corps reviewed its applicants so carefully. It did accept some who were considerably older than us. A woman who joined the group two years behind us, just before we left, was well into her 70s and starting on her third Peace Corps tour.

Many older Americans have family obligations, medical problems, and other constraints that make the Peace Corps unrealistic. Nonetheless, it is a proven program through which many Americans of all ages have served their country and the world. It isn’t as strange or exotic as some people back home suggest, and it can’t just be dismissed with, “Oh, I could never do that at my age.”

If you think Americans sign up to become Peace Corps Volunteers because they’re altruistic and want to help people around the world, you’re right, but not completely right.

If you think Americans sign up to become Peace Corps Volunteers because they’re altruistic and want to help people around the world, you’re right, but not completely right. A national survey of more than 11,000 returned Peace Corps Volunteers found their top three reasons for joining were “wanting to live in another culture,” “wanting a better understanding of the world,” and “wanting to help people build a better life.”

Simultaneously, the survey reported “a significant generational shift” in the importance Volunteers placed on acquiring job skills and experience during their service. Volunteers who served more recently placed “a greater emphasis on career development as a motivation for joining the Peace Corps,” it said. Just 30 percent of Volunteers who served in the 1960s identified “wanting to develop career and leadership skills” as an important motivation.” Among Volunteers who served in the 2000s, 68 percent cited this motivation.

A Volunteer who returned from Guatemala wrote: “I’m sure that my Peace Corps service helped me gain acceptance to a selective master’s degree program (because my grades as an undergraduate were disappointing, at best). Over the years, many people have told me that having the words ‘Peace Corps’ on my resume would only help me.” Indeed, the Peace Corps touts the career benefits of service. Its recruitment materials emphasize the importance of selfless service and cultural outreach, but they also highlight medical benefits, student loan deferrals, tuition reductions, and career networking opportunities.

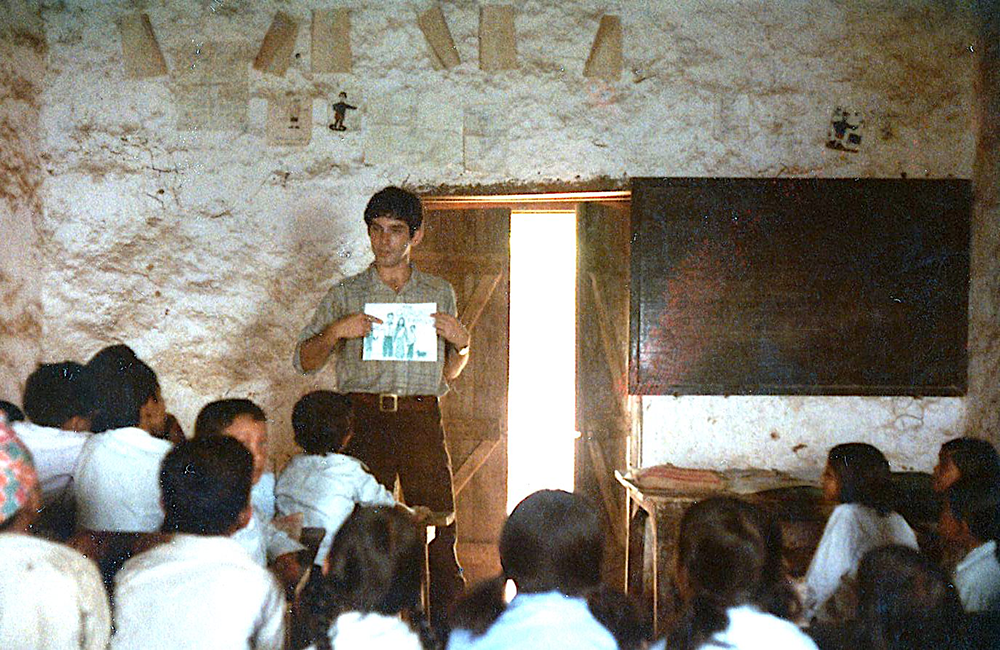

BACK WHEN I SERVED as a Volunteer in Nepal, we barely discussed resumes, grad school applications, and job prospects. America was the world’s dominant economic power; jobs were plentiful. Years later, when I first started talking with Duke students considering the Peace Corps, I was taken aback by how many of their questions were about career paths. Would serving in the Peace Corps help them get into law school, a public health program, or the Foreign Service? I always responded with encouragement and eventually came to see how their questions reflected new economic realities, not a diminishment in sincerity.

I developed an even greater admiration for today’s generation of Volunteers as I served beside them. They faced a more challenging economy but still chose to devote more than two years of their lives to serving others. No doubt, doing so enhanced their resumes and career prospects, but that was also true for young people who chose to serve in Teach for America or, for that matter, in the Marines. Life was complicated, just as it was for Champa and me, who joined the Peace Corps in Moldova mainly to serve others but also to pursue adventure and jump start our transition away from our workaday lives.

The most common question my American friends asked me after I moved to Moldova was whether I found being a Peace Corps Volunteer different from when I served in Nepal four decades earlier. My short answer was “Yes, of course,” but the experience still felt familiar. As before, I’d left my family and country to serve people in another country, learning their language and sharing their daily lives. After I’d been in Moldova for a while, though, several differences did stand out to me.

For starters, I was much more connected to the outside world than I was the first time. I had a smartphone, a laptop, and a Kindle, all linked to Wi-Fi. I regularly talked to my family. I could follow the U.S. election campaign and other news. I interacted online with my Moldovan partners and Peace Corps colleagues. In contrast, when I served in Nepal, I was cut off.

Pre-PowerPoint: David Jarmul on his first volunteer service with Peace Corps in Nepal, teaching his students using print photos in the classroom

Another change was that safety and security had become a much bigger deal for Volunteers worldwide. Neither terrorism nor street crime were serious problems in Moldova, yet our training was filled with security briefings. We were given detailed emergency action plans. I couldn’t leave my post overnight without notifying the staff. I couldn’t even enter the Peace Corps office without passing through a locked gate, a guard, and a metal detector — again, in a country with a low terror threat. In Nepal, I used to ride my bicycle past a front gate nominally staffed by a guard, and then stroll inside.

This new emphasis on security reflected a broader expansion in the Peace Corps infrastructure. There was so much more bureaucracy and physical stuff. My desk was piled with Romanian language workbooks, brochures on Moldovan culture, a “volunteerism action guide,” and more. I had dozens of resources on a computer thumb drive the Peace Corps gave me. There were detailed protocols for everything from paying a language tutor to taking a trip. In Nepal, our training was also excellent, but we had fewer resources and a lot less red tape.

When I joined the Peace Corps in Nepal, I was two years out of college, single, and eager to save the world. Now I was a father and grandfather and serving with my wife, whom I met in Nepal.

I was also serving in a different country this second time around. Moldova is in Eastern Europe, with an agricultural economy best known for its wine. Its population is almost entirely white and Orthodox Christian. Nepal is in the Himalayas and mainly Hindu, but mixed with Buddhists, Christians, and Muslims. Both countries have delicious food and fascinating customs, but they are as different as can be, except for both being landlocked.

Inevitably, the Peace Corps experience was different, too. What’s more, the world had changed over four decades. When I served in Nepal, the United States was still in a Cold War with the Soviet Union, which included Moldova. China was poor. Personal computers were new. Gay people could not get married. The idea of an African American president was almost unimaginable. After four decades, the Peace Corps had evolved to reflect this changed reality, such as with programs to combat HIV/AIDS or to “let girls learn.”

Most importantly, I had changed, too. When I joined the Peace Corps in Nepal, I was two years out of college, single, and eager to save the world. Now I was a father and grandfather and serving with my wife, whom I met in Nepal. I was much older and hopefully a bit wiser. In any case, I was in a different place in my life and not just geographically.

Festivities in Moldova: David celebrating his 65th birthday with his host family’s beloved grandmother, Bunica

In other words, I could watch Jimmy Kimmel or a YouTube video instead of fiddling with a shortwave radio to find a signal from the BBC, but the Peace Corps still had the same beating heart. Once again, I was working alongside a wonderful group of Americans to serve others and represent our country. I felt privileged to be among them. Who knows? Perhaps there was even a new form I was supposed to fill out to confirm this.

The Peace Corps has three goals, established by President Kennedy. The first is to build the local capacity of people in interested countries and help meet their needs for trained men and women. The second is to promote a better understanding of Americans among people in other countries. The third is to increase America’s awareness and knowledge of other cultures and global issues.

Our group of Volunteers met together many times but never had a session devoted to the Second Goal and Third Goal of Peace Corps. Not even once.

When it comes to changing the attitudes Americans have about people in developing countries, Peace Corps Volunteers are well-situated to provide facts, stories, and perspectives. Indeed, their mandate to promote cultural understanding in both directions became even more important after Trump’s election.

Almost all of our training and programmatic support, however, was focused on the first goal. My “community and organizational development” (COD) group spent countless hours learning about community needs assessment, community mapping, and community surveys. Champa’s English education group studied teaching techniques and pedagogy. Our overall group met together many times but never had a session devoted to the other two goals. Not even once.

Peace Corps Family: All smiles as David and Champa Jarmul pose for a photo with their granddaughters in Peace Corps attire.

When I was invited with other COD Volunteers to participate in a detailed review of our program, these goals never came up until I asked about them at the end. Peace Corps Moldova did add a session on communications for incoming Volunteers after I suggested it, and the training paid off with increased Volunteer blogging and other activity to promote cultural understanding. But it was one session and was never followed up.

A management rule is that the amount of time people and organizations spend on a topic reflects its importance to them. The tiny amount of time Peace Corps Moldova devoted to cross-cultural communications spoke for itself, although it did back Liuba’s innovations and encouraged Volunteers to get involved in activities such as Peace Corps Week.

My fellow Volunteers did amazing things at their job sites and in their communities, just like their counterparts around the world. Yet, they could have accomplished even more if the Peace Corps had made communications a real priority in its recruiting, training, program development, and assessment.

Worldwide, the Peace Corps has taken some steps to give its second and third goals more prominence, such as with international contests that encourage volunteers to produce videos or blogs. It has beefed up its online and social media activities and provided training for local staff around the world. It created a “Third Goal” office that maintains a media library and assists outreach activities. Some returned Volunteers also share their experiences and perspectives in various ways. All of this is good, but it was at the margins of what I saw discussed and supported while serving with Peace Corps Moldova.

To be sure, many of my fellow Volunteers did amazing things at their job sites and in their communities, just like their counterparts around the world. Yet, they could have accomplished even more if the Peace Corps had made communications a real priority in its recruiting, training, program development, and assessment. I was frustrated during my service to know the Peace Corps could have been more impactful in teaching our families and friends back home about distant places they may have regarded as mysterious or dangerous. At a time when President Kennedy’s latest successor was referring to developing countries as “shitholes,” their voices and experiences needed to be heard more widely.

Not Exactly Retired: More on David Jarmul’s life-changing journey and a link to ordering the book are here.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA first season as a wildland firefighter. It was one for the record books. see more

My first season as a wildland firefighter

By Colin McLaren

as told to Steven Boyd SaumPhoto by Colin McLaren

By October 2020, wildfires in the western U.S. burned an area larger than the state of New Jersey. A story from the front lines.

Typically when we’re out on a fire, we work 16 hour days: up before six and finishing with a pretty late dinner — whenever the work is really done. But recently two of the fires we worked overnight, to 9 a.m. the next morning.

We were on the Cold Creek Fire in Wenatchee, Washington. We went there directly from the Pearl Hill fire, a little east of Lake Chelan. Before that, the Chikamin fire, close to Leavenworth, the district we're based out of in Washington. Earlier in the summer I was down in Arizona on the Magnum fire, on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Then the Bighorn Fire, on Mount Lemmon outside Tucson. In between I went to Modoc National Forest in Northern California, and to the fire at Lava Beds National Monument.

The Bighorn Fire, near Tucson. Photo by Preshit Ambade

The California fires we were working around the clock. Everyone's a little fatigued. Basically all of September we had maybe three days off. But it’s valuable work.

This is my first year on a hand crew. I’m part of what’s referred to as the dig, typically using a tool called a scrape. Chainsaw teams cut the big stuff out of the way. The dig follows behind, scraping a perimeter in the dirt and trying to establish a line that fire will not cross.

The fire we were on most recently was pretty intense. We did a backburn, where you burn off of an established fire line to remove the excess fuels in between the main fire and the area you absolutely don't want the fire getting to. While we’re doing that, embers get sucked up from the heat and convection currents and can be spit out as far as a mile away. We had spot fires from embers, and we really had to rush around.

“One we ran from, it looked like a volcano erupting. Kind of a scary moment.” Photo by Colin McLaren

We’ve had to run from fires a couple times — which happens when it’s gotten too hot or winds have changed, and the fire could overtake you if you don’t hightail it out of there. A couple times people had to deploy fire shelters. One we ran from, it looked like a volcano erupting. Kind of a scary moment. Then we got in a safe place, organized, and went in and did direct suppression and some background stuff to protect the houses and nearby agriculture. We worked all night. In the morning, the fire basically put itself out because of the work we had done.

Wildland crew heads toward the fire. Photo by Colin McLaren

This is work I wanted to do after Peace Corps. It can be extremely difficult. There’s a refrain that you’re not a hero until you die. In terms of paychecks, most of us are the lowest level employees — technically “forestry aide” or “forestry technician.” After a disaster it’s: “Wildland firefighter died.” So there’s a discrepancy in how we’re treated as employees versus the reporting that goes on.

If we’re able to stop the fire, on an environmental level that's a lot of carbon not being released into the atmosphere. As wildfires get really bad, they get attention. Now the weather’s hotter and drier in September; historically, the West Coast should be getting rain sooner. This is one result of climate change — and it will get worse as the environment gets hotter. Some people don’t want to hear the the direct connection between climate change and how it has made the fire season longer. We’ve certainly been seeing it in California, making the extremes more extreme. In Seattle, the past weekend was the smokiest that it has ever been.

Cold Creek Fire in Wenatchee, Washington. Photo by Krista Williams

I lived for two years in Nepal as a Peace Corps Volunteer, 2017–19. I remember talking with older people in my village—which, by the way was not in the mountains; most of Nepal is actually in the subtropics. The pre-monsoon season has gotten hotter and drier; their whole agriculture calendar is changing. And communities have basically no safety buffer. Will they be able to adapt to a more intense climate? They’re not climate refugees yet, but whole corn crops might be at risk.

American society is not set up to combat climate change. We’re some of the worst perpetrators on the global level. The Peace Corps experience I had showed me the importance of community: how a strong, extended family structure is very capable of dealing with shortages and other bigger scale problems that might cripple individual households. Helping each other out.

This story appears in the Fall 2020 edition of WorldView magazine. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleGlobal evacuation — and friends and communities left behind see more

Photos from Nepal, Timor Lesté, Guinea, and Jamaica

Along with the dozens of stories we’ve shared from Peace Corps Volunteers evacuated from around the world, here are snapshots from more Volunteers. They capture the friendships and communities left behind. And they capture the heartbreak of leaving.

Nepal | Eddie De La Fuente

When Peace Corps announced the global evacuation, we were actually en route to visit our permanent sites a month early. I, and many of the other agriculture volunteers, never made it to our sites given the distance; I had just finished two all-day bus trips and was still another day-and-a-half away when we got the order to get back to Kathmandu ASAP.

We gathered at the Nepal Peace Corps headquarters and effectively had a close of service conference after only two months in the country, and only about four to five days away from being able to swear in as full Volunteers.

The Nepal Peace Corps staff was very compassionate though all of this; our Country Director and her partner even brought their brand new puppy and American candy to help comfort us.

We are, in my opinion, an extraordinarily cohesive and supportive group of people and I believe that these sentiments — as well as our continued, steady communication and mutual support — is truly exemplified in these photos.

Nepal welcomed us so readily and so fully that we were all absolutely heartbroken when we were told we were going home. I even had the good fortune to sit next to a gentleman on the final flight from Qatar to Nepal that served as an language instructor for Peace Corps back in the ‘70s!

This photo of the gentleman greeting was actually from our first night in Nepal. He was far from the only person that was unabashedly eager to meet us and get to know us — and for us to know them.

Nepal farewell: Training to become Volunteers, Rachel Ramsey, left, and Elyse Paré had to evacuate instead.

Timor Lesté | Andre De Mello

Andre De Mello arrived in Timor-Lesté in late 2019 in the country’s tenth group of Peace Corps volunteers. After training, he settled in with a host family and started teaching. But his two-year commitment was not to be. Read more about his story here.

“This picture was taken after Sunday mass in the Grotto located by the church in Railaco. The person to my left, wearing the white-dotted blue shirt, is my host brother Adi Carvalho. The person to my right is the son of the Chefe de Suco (sort of like a community leader).”

Guinea | Colt Bradley

Home: Mooresville, North Carolina

He served as a Volunteer in Kankan, Guinea, where he taught math and chemistry and served as the head of the Peace Corps Guinea Media Team.

Walk on: Colt Bradley heading home during the dry season in Guinea, West Africa.

Transport for Volunteer Colt Bradley and other visitors to the islands from Conakry.

Jamaica | Kate Rapp

Students at Spring Garden Infant and Primary School, where Volunteer Kate Rapp worked with counterpart Lorraine Clarke.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleJim Damico: lessons from and for the teacher see more

Nobody wanted it to happen this way. Evacuation stories and the unfinished business of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world.

Nepal | Jim Damico

Home: Kansas City, Missouri

I am a three time Volunteer. I previously served in Thailand (2014–18) and Mongolia (2018). In Nepal I had just finished my first school year. When I sat down to tell this story, I was in a hotel in Kansas City in my 14-day quarantine.

After a year you have made connections; you see where you can go. I had an awesome host family that I miss dearly. I miss the little mud-floor kitchen where we ate our meals — and where my host sister makes selroti, a kind of donut made for special occasions. I miss the view from my school: a stunning vista of the Himalayas. After the monsoon season, when the skies are clear, you can see white-capped mountains from horizon to horizon.

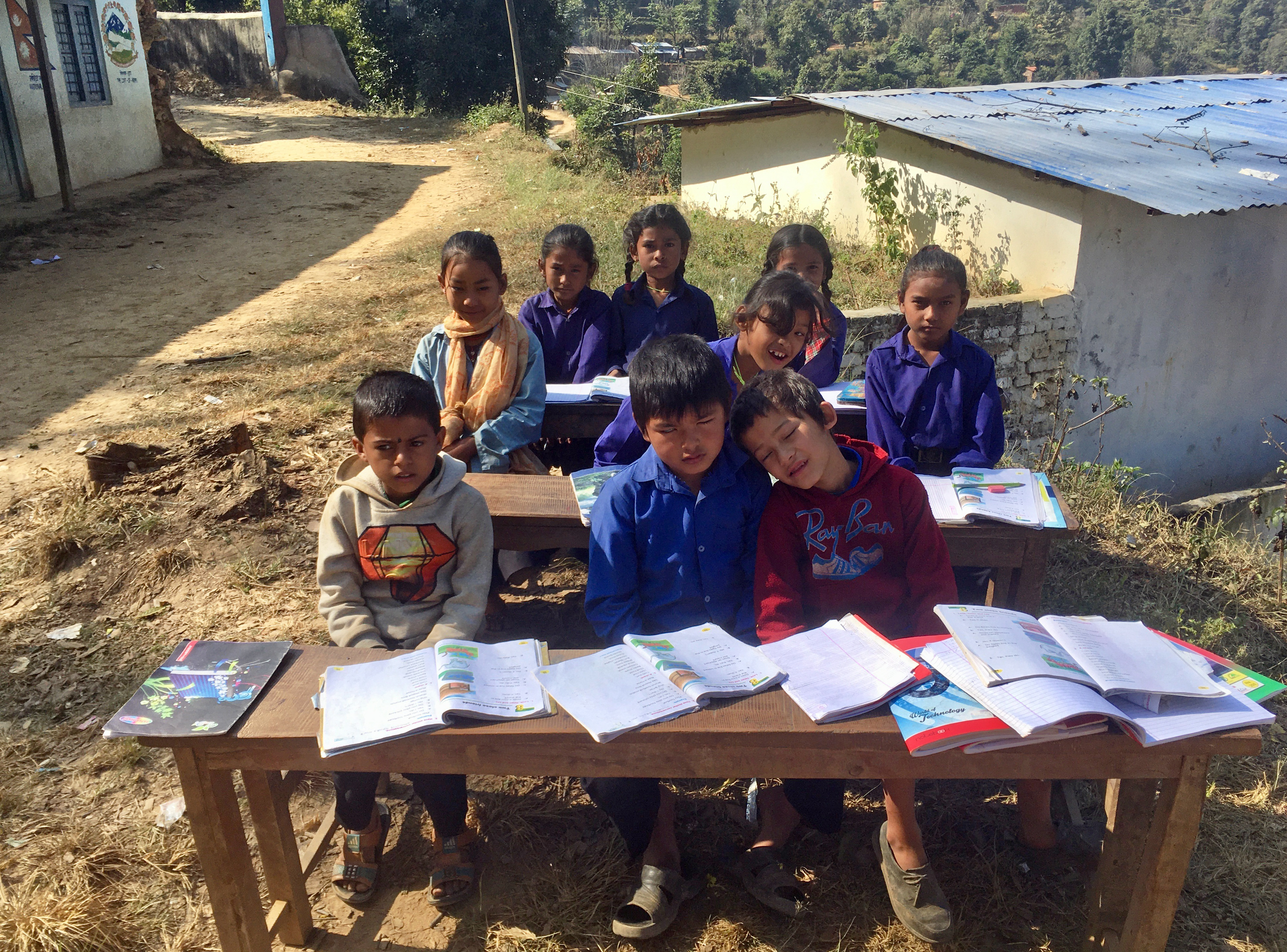

The teacher is in: My fourth-grade students were always joking and playing. And one day they wanted to wear my topi, a traditional Nepali hat. But once they had it on, they decided that they were the teacher and got up to teach the class.

I left students behind — many of whom teachers had written off. When I began teaching, more than half of my fifth graders couldn’t read or write English, though they had studied it since kindergarten. Besides low academics, they had behavioral issues. It was tough teaching them, but over the year they became better students. I loved them. Many of them have started to be excited about learning English. Hopefully that will continue in their other courses, too.

We want meaningful work, we want a good education for our children, and we all genuinely want peace and prosperity.

Schools is out: In the winter months, some of the classrooms were dark, damp and downright freezing. So we carried the student benches outside and had class in the warm sunshine. We must have done this for several weeks.

I turned 61 when I was in Nepal. For decades I had a career as a mechanical engineer. Back in the 1970s I’d looked into Peace Corps, but the only engineers they were looking for at the time were civil engineers. One thing I’ve learned working internationally over my life: On a lot of levels, we’re all the same, no matter what country. We want meaningful work, we want a good education for our children, and we all genuinely want peace and prosperity.

See more from Jim's service here

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how: