Activity

-

Steven Saum posted an articleCelebrate Peace Corps Day by honoring the 2023 recipients of the Franklin H. Williams Award. see more

Celebrate Peace Corps Day by honoring the 2023 recipients of the Franklin H. Williams Award.

By NPCA Staff

The Franklin H. Williams Award is presented by the Peace Corps agency and honors ethnically diverse Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who have demonstrated a commitment to civic engagement, service, diversity, inclusion, world peace, and to the Peace Corps’ Third Goal — to strengthen Americans’ understanding of the world and its peoples.

An advocate for civil rights and an early architect of the Peace Corps, Franklin Williams also served as ambassador to the U.N. and U.S. ambassador to Ghana.

The award was established in 1999, and past winners include Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative; Ambassador Charles Baquet III; and Sia Barbara Ferguson Kamara, who served as associate commissioner of Health and Human Services.

The ceremony takes place at Planet Word in Washington, D.C. at 7 p.m. Eastern. More information here.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity is only a demographic concept, with an emphasis on numbers see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Hermence Matsotsa-Cross

By Hermence Matsotsa-Cross

Peace Corps Volunteer in Togo 1999–2001 | Founder and CEO of Ubuntu Speaks

Below are edited excerpts. Watch the full program here.

My father was a Volunteer in Gabon in the early ’70s, where he met my mother, a Gabonese woman from one village he worked in. So I’m very much the product of Peace Corps. Growing up, I always heard Peace Corps stories; more important was the idea of volunteerism, how important that was, and working with other people to achieve goals.

I wanted to do Peace Corps after high school. My father reminded me that I had to go to college first. When I got to college, I realized that as a kinesthetic learner, four years of sitting in class was too painful. I took a year off to work with an international development organization as a reforestation volunteer in Ecuador.

My senior year I put in my application. They told me I would be going to Uzbekistan. After speaking to my father and the Peace Corps, I said, “Is there a way that I can go back to Africa?” They sent me to Togo, where I became a girl’s education empowerment Volunteer — one of only three African American volunteers in a group of 40-plus.

Training was painful; I knew I stood out because I was Black. I wanted to stand out because I was passionate about the work and being willing to learn from others. Oftentimes, it was, “You can’t be a Volunteer — you’re Black … You’re African, so you can’t go with them.” On a daily basis, I felt excluded. I felt as though Peace Corps was not supporting me. When one of the three Black Americans decided to leave during training, I was heartbroken.

Peace Corps is very much about bringing Americans to a place where they will be challenged, forced to shed misconceptions and acquire a level of cultural intelligence and cultural communication to work with people who are different.

Black Volunteers and Volunteers who are people of color are forced — to a level that white Peace Corps Volunteers may not feel — to describe the diversity that exists in the United States. Not only Volunteers but also staff did not know the history, diversity, and richness that exists within our country that makes us all Americans; therefore it was difficult for them to support us.

I realized that inclusion was essential for me to be able to do my work. I was embraced for being honest about what I didn’t know, about what I wanted to learn. Peace Corps is very much about bringing Americans to a place where they will be challenged, forced to shed misconceptions and acquire a level of cultural intelligence and cultural communication to work with people who are different.

Some ways Peace Corps can help facilitate that understanding is to be honest about what the experience may be, pre-departure: difficulties, challenges — the fact that Peace Corps staff often don’t know how to treat you or communicate with you. There needs to be mentorship for Volunteers, pre-departure and throughout service. The goal is for you to finish your experience and not come home bitter, but feeling this experience is like no other — and that you left footprints in this world to make it a better place.

Diversity is only a demographic concept — this idea that, the more numbers you have, you can say, “We’re diverse.” The effort starts at belonging.

Peace Corps can be a great model for other international organizations seeking to implement the sense of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging — and showcase to the world that we can be one in the sense that “one” means being able to see each other for who we are, and to love and respect each other for that. Diversity is only a demographic concept — this idea that, the more numbers you have, you can say, “We’re diverse.” The effort starts at belonging. There will be more people of color, more African Americans, willing to be part of Peace Corps, or any institution, if they feel they belong.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated January 19, 2022.

Hermence Matsotsa-Cross leads work incorporating the South African philosophy of Ubuntu human interconnectedness. Her organization has led projects with private and nonprofit organizations, global health and federal, state and community development programs, including the Peace Corps, CDC, and World Health Organization.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity in the Peace Corps: It’s over 50 years and we haven’t moved the needle very far. see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Howard Dodson

By Howard Dodson

Peace Corps Volunteer in Ecuador 1964–67 | Director, Howard University Libraries

I wanted to join the Peace Corps the day Kennedy announced it was going to happen. I was a junior in undergraduate school — first on both sides of my family on the verge of graduating from college. I took the idea home to my parents. My father’s response was: “Let me see if I understand this. You’re going to finish a college degree, go away overseas for $125 a month for two years. What?” I got talked out of it the first time. The second time I decided that’s what I was going to do.

I had read The Ugly American by Lederer and Burdick, about foreign service people working overseas who were, frankly, embarrassing representations of what Americans should be. I knew I could do a better job of representing America than that.

I was offered a job teaching, and I coached a basketball team. I was the only African American in my training group — and one of about three with Peace Corps in Ecuador. But I managed to travel around South America, getting to know people of African descent. It led to my professional training and study of the African diaspora in the world. I hope that there will be opportunities for more African Americans to have meaningful, substantive experiences with peoples of African descent and others around the world, especially in this time when America’s reputation has been somewhat tarnished by our public presence in other parts of the world.

Diversity in the Peace Corps: We haven’t moved the needle very far, both at the level of staffing and Volunteers. So what is wrong with our approach? We continue to do the same things.

Diversity in the Peace Corps: It’s over 50 years that we’ve been in this conversation. We haven’t moved the needle very far, both at the level of staffing and Volunteers. So what is wrong with our approach? We continue to do the same things. I know, from my period as a Volunteer, recruiting officer, director of minority recruitment, and training officer: What we call structural racism was present in Peace Corps from day one. The solution was find three or four more people so we don’t look bad. That doesn’t solve the problem. Because of the transient nature of people’s engagement with Peace Corps as an institution, you spend two years and what you’ve gained is gone; whatever was working has not been re-created in the structure.

There were assumptions about who made good Volunteers, what you look for — and they don’t have anything to do with Black people. The diversity and inclusion framework is at the center of public conversations now. I think it gets in the way of finding real answers, because nine times out of ten they’re looking for racial representation rather than a systemic problem solver. Simply putting some Black faces in places does not change any damn thing.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Howard Dodson is the director emeritus of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which he led for 27 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity is only a demographic concept. The effort starts at belonging. see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

By Sia Barbara Kamara

Peace Corps Volunteer Liberia 1963–65 | Educational Consultant

I live in Washington, D.C. But I grew up in what would be considered public housing in North Carolina. I graduated from Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college. The Peace Corps recruiter came to campus just before graduation. I said, Yes, if I can go to Africa. I graduated with a degree in mathematics and physics, and a minor in economics. My goal was to be a scientist.

When I went to Liberia, my parents were very supportive. They always had African students at my college come home and visit. During my time in Peace Corps, when so many African countries obtained independence, every time a country changed its name, they got a new atlas. They sent Ebony magazines to me. I was way up-country, and there were four African American Volunteers in my group; by the time that magazine reached me, it was all dog-eared, because people along the way would read it.

I was a teacher and worked with young women; we created a track team, and they went on to be national champions. As a Volunteer, I had been treated like an African queen; people welcomed the Black American. But they said, “We don’t let foreigners teach below third grade.” That’s when children learn about their own culture, and they learn it from people around them. Eventually they did allow me to do it.

A life of learning: Sia Barbara Kamara with a student in Liberia, where she served with the Peace Corps. She now advises the Ministry of Education of Liberia. Photo courtesy Friends of Liberia

When I returned to the States, I served as a Peace Corps recruiter in the Northeast. Sargent Shriver would have me lead sometimes, because he thought that it was important for people of color to be seen in leadership positions. Then I served on the team recruiting at historically Black colleges. I left to become an intern in a program organized by the wife of a former Peace Corps country director in Nigeria, helping historically Black colleges obtain resources. I wrote grants to expand an early childhood program. I knew little about what I was doing, but Peace Corps gave me the courage to do almost anything. I worked with a superintendent of schools and helped organize a master’s program for African Americans to obtain degrees in early childhood education. I had the opportunity to visit early childhood programs in every Southern state and document what they were doing. I presented a paper and met the president and dean of Bank Street College in New York. They asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

The president and dean of Bank Street College in New York asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

I went on to work in North Carolina, responsible for an eight-state Head Start training program. Then I went to work for the governor of North Carolina. President Carter asked me to come work as an associate commissioner in the Department of Health and Human Services, responsible for the national Head Start program, the Appalachian Regional Commission child development programs, childcare regulations, and research and demonstration programs. Then I worked for four mayors in Washington, D.C., to help transform the early childhood system. For the last 10 years, I have been a consultant in early childhood to the Ministry of Education in Liberia. I’ve returned to that place where I got my start, working in Africa.

Early childhood educational center: Sia Barbara Kamara, right, and a sign announcing the work of a center named for her. Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

When I think about current and returned Volunteers, many need support — networking opportunities, validation, mentoring. It’s important that we continue to provide these during training and reentry, and as people are in service.

People in Liberia have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

I’m very active in our Friends of Liberia group. However, I’m the only African American in our education work group. We have been able to focus on building human capacity to help groups obtain the resources and background and know-how they need to sustain programs. People there have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

Going forward, Peace Corps needs to understand what Volunteers are experiencing during training or when they go out. I had spent four years going to jail as part of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. When we were undergoing Peace Corps training in Syracuse, New York, they didn’t want us to go and participate in a march. That was a part of my DNA. It went all the way to Washington for Sargent Shriver to have to make a decision. We marched together.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022.

Sia Barbara Ferguson Kamara received the Peace Corps Franklin H. Williams Award for Distinguished Service in 2012. At Head Start, she managed a budget of approximately $1 billion. When she started, there were 100,000 children in the program; it grew to serve 122 million under her watch.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAsian American and Pacific Islander leaders have a conversation on Peace Corps, race, and more. see more

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity. A conversation convened as Part of Peace Corps Connect 2021.

Image by Shutterstock

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are currently the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S., but the story of the U.S. AAPI population dates back decades — and is often overlooked. As the community faces an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes and the widening income gap between the wealthiest and poorest, their role in politics and social justice is increasingly important.

The AAPI story is also complex — 22 million Asian Americans trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent, each with unique histories, cultures, languages, and other characteristics. Their unique perspectives and experiences have also played critical roles in American diplomacy across the globe.

For Peace Corps Connect 2021, we brought together three women who have served or are serving as political leaders to talk with returned Volunteer Mary Owen-Thomas. Below are edited excerpts from their conversation on September 23, 2021. Watch the entire conversation here.

Rep. Grace Meng

Member, U.S. House of Representatives, representing New York’s sixth district — the first Asian American to represent her state in Congress.

Julia Chang Bloch

Former U.S. ambassador to Nepal — the first Asian American to serve as a U.S. ambassador to any country. Founder and president of U.S.-China Education Trust. Peace Corps Volunteer in Malaysia (1964–66).

Elaine Chao

Former Director of the Peace Corps (1991–92). Former Secretary of Labor — the first Asian American to hold a cabinet-level post. Former Secretary of Transportation.

Moderated by Mary Owen-Thomas

Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines (2005–06) and secretary of the NPCA Board of Directors.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. This is not a recent story — and it’s often overlooked. I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines, and I happen to be Filipino American.

During my service, people would say, “Oh, we didn’t get a real American.” I used to think, I’m from Detroit! I’m curious if you’ve ever encountered this in your international work.

Julia Chang Bloch: With the Peace Corps, I was sent to Borneo, in Sabah, Malaysia. I was a teacher at a Chinese middle school that had been a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. The day I arrived on campus, there was a hush in the audience. I don’t speak Cantonese, but I could understand a bit, and I heard: “Why did they send us a Japanese?” I did not know the school had been a prisoner of war camp. They introduced me. I said a few words in English, then a few words in Mandarin. And they said, “Oh, she’s Chinese.”

I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised me I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.”

In Nepal, where I was ambassador, when I arrived and met the Chinese ambassador, he said, “Ah, China now has two of us.” I said, “There’s a twist, however. I am a Chinese American.” He laughed, and we became friends thereafter. On one of my trips into the western regions, where there were a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers and very poor villages, I was welcomed lavishly by one village. I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.” He said to her, “There she is.” “Oh, no,” she said. “She is not the American ambassador. She’s Nepali.”

Those are examples of why AAPI representation in foreign affairs is important. We should look like America, abroad, in our embassies. We can show the world that we are in fact diverse and rich culturally.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Secretary Chao, at the Labor Department you launched the annual Asian Pacific American Federal Career Advancement Summit, and the annual Opportunity Conference. The department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics began reporting the employment data on Asians in America as a distinct category — a first. You ensured that labor law materials were translated into multiple languages, including Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean. Talk about how those came about.

Elaine Chao: Many of us have commented about the lack of diversity in top management, even in the federal government. There seems to be a bamboo ceiling — Asian Americans not breaking into the executive suite. I started the Asian Pacific American Federal Advancement Forum to equip, train, prepare Asian Americans to go into senior ranks of the federal government.

The Opportunity Conference was for communities of color, people who have traditionally been underserved in the federal government, in the federal procurement areas. Thirdly, in 2003 we finally broke out Asians and Asian American unemployment numbers for the first time. That’s how we know Asian Americans have the lowest unemployment rate. Labor laws are complicated, so we started a process translating labor laws into Asian, East Asian, and South Asian languages, so that people would understand their obligations to protect the workforce.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized.

Grace Meng: I am not a Peace Corps Volunteer, but I am honored to be here. My former legislative director, Helen Beaudreau (Georgia 2004–06, The Philippines 2010–11), is a twice-Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. I am incredibly grateful for all of your service to our country, and literally representing America at every corner of the globe.

I was born and raised here. This past year and a half has been a wake-up call for our community. Asian Americans have been discriminated against long before — starting with legislation that Congress passed, like the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Japanese American citizens being put in internment camps. We have too often been viewed as outsiders or foreigners.

I live in Queens, New York, one of the most diverse counties in the country, and still have experiences where people ask where I learned to speak English so well, or where am I really from. When I was elected to the state legislature, some of us were watching the news — a group of people fighting. One colleague turned to me and said, “Well, Grace knows karate, I’m sure she can save us.”

By the way, I don’t know karate.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized. I didn’t necessarily come to Congress just to represent the AAPI community. But there are many tables we’re sitting at, where if we did not speak up for the AAPI community, no one else would.

At the root of hate

Julia Chang Bloch: I believe at the root of this anti-Asian hate is ignorance about the AAPI community. It’s a consequence of the exclusion, erasure, and invisibility of Asian Americans in K–12 school curricula. We need to increase education about the history of anti-Asian racism, as well as contributions of Asian Americans to society. Representative Meng, you should talk about your legislation.

Grace Meng: My first legislation, when I was in the state legislature, was to work on getting Lunar New Year and Eid on public school holidays in New York City. When I was in elementary school, we got off for Rosh Hashanah; don’t get me wrong, I was thrilled to have two days off. But I had to go to school on Lunar New Year. I thought that was incredibly unfair in a city like New York. Ultimately, it changed through our mayor.

In textbooks, maybe there was a paragraph or two about how Asian Americans fit into our American history. There wasn’t much. One of my goals is to ensure that Asian American students recognize in ways that I didn’t that they are just as American as anyone else. I used to be embarrassed about my parents working in a restaurant, or that they didn’t dress like the other parents.

Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Julia Chang Bloch: I wonder about data collection. We’re categorized as AAPI — all lumped together. And data, I believe, is collected that way at the national, state, and local levels. Is there some way to disaggregate this data collection and recognize the differences?

Elaine Chao: A very good question. Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Two obstacles stand in the way. One is resources. Unless there is thinking about how to do this in a systemic, long-term fashion, getting resources is difficult; these are expensive undertakings. Two, there’s sometimes political resistance. Pew Charitable Trust, in 2012, did an excellent job: the first major demographic study on the Asian American population in the United States. But we’re coming up on 10 years. That needs to be revisited.

Role models vs. stereotypes

Elaine Chao: Ambassador Julia Chang Bloch and Pauline Tsui started the organization Chinese American Women. I remember coming to Washington as a young pup and seeing these fantastic, empowering women. They blazed so many trails. They gave voice to Asian American women.

I come from a family of six daughters. I credit my parents for empowering their daughters from an early age. They told us that if you work hard, you can do whatever you want to do. We’ve got to offer more inspiration and be more supportive.

Julia Chang Bloch: Pauline Tsui has unfortunately passed away. She had a foundation, which gave us support to establish a series on Asian women trailblazers. Our inaugural program featured Secretary Chao and Representative Judy Chu, because it was about government and service. Our next one is focused on higher education. Our third will be on journalism.

I want, however, to leave you with this thought. The Page Act of 1875 barred women from China, Japan, and all other Asian countries from entering the United States. Why? Because the thought was they brought prostitution. The stereotyping of Asian women has been insidious and harmful to our achieving positions of authority and leadership. That’s led also to horrible stereotypes that have exoticized and sexualized Asian women. Think about the women who were killed in Atlanta.

That intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something we need to continue to combat.

Grace Meng: There was the automatic assumption, in the beginning, that they were sex workers — these stereotypes were being circulated. I had the opportunity with some of my colleagues to go to Atlanta and meet some of the victims’ families, to hear their stories. That really gave me a wake-up call. I talked about my own upbringing for the first time.

I remember when my parents, who worked in a restaurant, came to school, and they were dressed like they worked in a restaurant. I was too embarrassed to say hello. Being in Atlanta, talking to those families, made me realize the sacrifices that Asian American women at all levels have faced so that we could have the opportunity to be educated here, to get jobs, to serve our country. And that intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something that we need to continue to combat.

Julia Chang Bloch: We’ve talked about the sexualized, exoticized, and objectified stereotype — the Suzie Wongs and the Madame Butterflys. However, those of us here today, I think would fall into another category: the “dragon lady” stereotype. Any Asian woman of authority is classified as a dragon lady — a derogatory stereotype. Women who are powerful, but also deceitful and manipulating and cruel. Today it’s women who are authoritative and powerful.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Growing up, I was sort of embarrassed of my mom’s thick Filipino accent; she was embarrassed of it, too. I was embarrassed of the food she would send me to school with — rice, mung beans, egg rolls, and fish sauce. And people would ask, “What is that?” Talk about how your self-identity has evolved — and how you view family.

You do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Grace Meng: I don’t know if it’s related to being Asian, but I was super shy as a child. And there weren’t a lot of Asians around me. I was the type who would tremble if a teacher called on me; I would try to disappear into the walls. When I meet people who knew me in school, they say, “I cannot believe you’re in politics.”

What gave me strength was getting involved in the community, seeing as a student in high school, college, and law school that I could help people around me. After law school I started a nonprofit with some friends. We had senior citizens come in with their mail once a week, and we would help them read it. It wasn’t rocket science at all.

I tell that story to young people, because you do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Julia Chang Bloch: At some point, in most Asian American young people’s lives, you ask yourself whether you are Chinese or American — or, Mary, in your case, whether you’re Filipino or American.

I asked myself that question one year after I arrived in San Francisco from China. I was 10. I entered a forensic contest to speak on being a marginalized citizen. I won the contest, but I didn’t have the answer. At university, I found Chinese student associations I thought would be my answer to my identity. But I did not find myself fitting into the American-born Chinese groups — ABCs — or those fresh off the boat, FOBs. Increasingly, my circle of friends became predominantly white. I perceived the powerlessness of the Chinese in America. I realized that only mainstreaming would make me be able to make a difference in America.

After graduation, I joined the Peace Corps, to pursue my roots and to make a difference in the world. Teaching English at a Chinese middle school gave me the opportunity to find out once and for all whether I was Chinese or American. I think you know the answer.

My ambassadorship made me a Chinese American who straddles the East and the West. And having been a Peace Corps Volunteer, I have always believed that it was my obligation to bring China home to America, and vice versa. And that’s what I’ve been doing with the U.S.-China Education Trust since 1998.

We should say representation matters. Peace Corps matters, too.

WATCH THE ENTIRE CONVERSATION here: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity

These edited remarks appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022. -

Orrin Luc posted an articleThe program you may not know that inspired JFK. And how we change what America looks like abroad. see more

The past: The program you may not know about that inspired JFK. The future: How we change what America looks like abroad.

Photo: Rep. Karen Bass, who delivered welcoming remarks for the event, part of the Ronald H. Brown Series, on September 14, 2021.

On September 14, 2021, the Constituency for Africa hosted, and National Peace Corps Association sponsored, a series of conversations on “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers.” Part of the annual Ronald H. Brown Series, the event brought together leaders in government, policy, and education, as well as some key members of the Peace Corps community.

Constituency for Africa was founded and is led by Melvin Foote, who served as a Volunteer in Eritrea and Ethiopia 1973–76. In hosting the program, he noted how the Peace Corps has played an instrumental role in training members of the U.S. diplomatic community. “Unfortunately, the number of African Americans serving in the Peace Corps has always been extremely low,” he wrote. By organizing this forum, he noted that CFA is attempting to build a community of Black Americans “who served in the Peace Corps in order to have impact on U.S. policies in Africa, in the Caribbean, and elsewhere around the world, and to form a support base for African Americans who are serving, and to encourage other young people to consider going into the Peace Corps.”

Representative Karen Bass (D-CA), Chair of the House Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health, delivered opening remarks. “I have traveled all around Africa, as I know so many of you have,” she said. “And we would love to see the Peace Corps be far more diverse than it is now. Launching this effort now, diversity and inclusion has to be a priority for all of us, including us in Congress. And we have to continue to try and reflect all of society in every facet of our lives … I am working to pass legislation to diversify even further the State Department, and looking not just on an entry level, but on a mid-career level. This effort that you’re doing today is just another aspect of the same struggle. So let me thank you for the work that you’re doing. And of course, Mel Foote as a former Peace Corps alum, and I know his daughter is in the Peace Corps. You’re just continuing a legacy and ensuring the future that the Peace Corps looks like the United States.”

“You’re continuing a legacy and making sure that in the future the Peace Corps looks like the United States.”

— Karen Bass, Member, U.S. House of Representatives

Read and Explore

The 2021 Anniversary Edition of WorldView magazine includes some keynote remarks and discussions that were part of the event.

Operation Crossroads Africa and the “Progenitors of the Peace Corps”

Reverend Dr. Jonathan Weaver | Pastor at Greater Mt. Nebo African Methodist Episcopal Church; Founder and President, Pan African Collective

An Inclusive State Department Is a National Security Imperative

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley | Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, U.S. Department of State

Diversity and Global Credibility

Aaron Williams | Peace Corps Director 2009–12

“First Comes Belonging”

Remarks and discussion with Returned Peace Corps Volunteers Howard Dodson, Sia Barbara Kamara, and Hermence Matsotsa-Cross. Discussion moderated by Dr. Anthony Pinder.

Watch the Program

Remarks were also delivered by Melvin Foote, founder and CEO of Constituency for Africa; Glenn Blumhorst, President and CEO of National Peace Corps Association; Dr. Darlene Grant, Senior Advisor to National Peace Corps Director; and Kimberly Bassett, Secretary of State for Washington, D.C., who welcomed participants on behalf of Mayor Muriel Bowser. Watch the entire event here.

Learn More

The Constituency for Africa was founded in 1990 in Washington, D.C., when a group of concerned Africanists, interested citizens, and Africa-focused organizations developed a strategy to build organized support for Africa in the United States. CFA was charged with educating the U.S. public about Africa and U.S. policy on Africa; mobilizing an activist Constituency for Africa; and fostering cooperation among a broad-based coalition of American, African, and international organizations, as well as individuals committed to the progress and empowerment of Africa and African people.

CFA also founded and sponsors the annual Ronald H. Brown African Affairs Series, which is held in conjunction with the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) Legislative Week each September. The series honors the late U.S. Commerce Secretary for his exemplary accomplishments in building strategic political, economic, and cultural linkages between the United States and Africa. More than 1,000 concerned individuals and organizational representatives attend each year, in order to gain valuable information and build strategic connections to tackle African and American challenges, issues, and concerns.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWe need a Peace Corps and a diplomatic corps that truly represents all of America. see more

Our public service institutions, whether it’s Peace Corps or the Department of State, must do better. And your work is how we change that.

Photo by Freddie Everett / State Department

By Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley

Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, U.S. Department of State

I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Oman nearly four decades ago, and Peace Corps is where I met my husband. Like many of you, Peace Corps changed the trajectory of my life. For me and many colleagues at the Department of State, Peace Corps also launched my career in diplomacy. When I joined the Peace Corps in Oman, I was the only African American in my cohort of about 15 people. Four decades later, I am still one of the only African American women at policymaking tables. I was one of a handful of African American women to rise to the level of ambassador in the Department of State.

My story is backed up by the data. These racial disparities are deep and go back decades. The Government Accountability Office released data that in 2002 the number of African American women in the foreign service was a shockingly low 2 percent. Almost 20 years later, that only went up to 3 percent. Our public service institutions, whether it’s Peace Corps or the Department of State, must do better. I am tired of being alone. And your work is how we change that.

The Peace Corps is a critical pipeline to the civil and foreign service. An African American colleague in my office said she had no idea that Peace Corps was for people who looked like her. She assumed it was a leisure activity for people who come from privilege. Another RPCV in my office, also a woman of color, said of the 50 members of her cohort in Jordan, fewer than 10 were people of color; almost all the other people of color left within a year. She and another PCV of color were the only two to stay the full two years. Another colleague who works at the U.S. mission in the United Nations said that her dream was to join the Peace Corps. But because she was in a wheelchair, she was denied entry. When the Peace Corps said no, she took the foreign service exam; she passed with flying colors, both the oral and written exams. Yet once again, she was barred from joining because of worldwide availability.

My road map for building a State Department that looks more like America is grounded in three core values: intentionality, transparency, and accountability. And past practice has shown any organization focused on these three will be able to make systemic change.

The real question we’re grappling with today is how do we both recruit and retain diverse cohorts, as well as make our respective institutions more equitable, inclusive, and accessible? When Secretary Blinken appointed me as chief diversity officer, he made clear that my mandate is to change the part of the State Department’s culture — the norms and behaviors and biases — that stifle diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA). My road map for building a State Department that looks more like America is grounded in three core values: intentionality, transparency, and accountability. And past practice has shown any organization focused on these three will be able to make systemic change.

First, we need to be intentional. This means changing the culture of the State Department so that every single employee feels invested in advancing the DEIA work. Secretary Blinken has stated many times that an inclusive workforce is not just a “nice to have,” it is a national security imperative. This goes for Peace Corps exactly the same way as it does for the State Department. The United States is the most diverse and powerful nation in the world. Other countries are watching us, and when we fail to live up to our ideals, our adversaries are standing in wait to exploit our shortcomings. That is why it’s critical that we integrate the DEIA work as a lens not only to reform our institutions on the inside, but to guide how we conduct our foreign policy. Our team is also finalizing the department’s five-year diversity and inclusion strategic plan. My office will oversee the implementation of it. We have had countless listening sessions over the last few years; some who have worked on it would say endless listening sessions. But we need concrete action. And we need to accelerate movement on issues that have been ignored for far too long.

Secondly, we need to be transparent. If we are serious about addressing systemic inequities, then we need to be transparent about what we are dismantling. This means collecting disaggregated demographic data on hiring, assignments, promotions, attrition, and other key milestones in one’s professional career. This will help us better understand who is at the table and why we see fewer underrepresented groups rising through the ranks. When we have access to analyze disaggregated diversity data, we are better equipped to make the case for resources and policies we need to make our institutions more equitable, inclusive, and accessible for all.

Lastly — and perhaps most importantly, from my view — we need to be accountable. While the State Department and many institutions have excellent accountability policies on paper, there is sometimes an informal culture that hardwires many of us — including from underrepresented groups — to keep our heads down, to not rock the boat. I’m intent on changing this dynamic by strengthening accountability mechanisms that we have in place and activating the courage that is inside of all of us. We all need to do our part. Speak up, even when it’s uncomfortable. This is how we will retain and increase the presence and promotion of underrepresented groups.

To address the challenges of the 21st century, we need a Peace Corps and a diplomatic corps that truly represents all of America.

The fact that we’re talking about diversity isn’t new. There have been, for many decades, many efforts to diversify the Department of State. What is new is that we are now taking action, speaking forthrightly and honestly about where we have failed and where we need to go. We are in a moment of historic alignment. It’s not just the State Department or Peace Corps that is committed to advancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility. It is at all levels of government, including the White House and our partners on Capitol Hill. We are living in extraordinarily complex times: a once-in-a-generation pandemic to a reckoning on race and daily threats to democracy at home and abroad. To address the challenges of the 21st century, we need a Peace Corps and a diplomatic corps that truly represents all of America. And if we’re going to succeed in doing this, it is going to take all of us. And we can do this. We can get it done.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 2021 Anniversary Edition of WorldView magazine.

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley is the first person to serve as chief diversity and inclusion officer in the history of the U.S. State Department. She was the first woman to lead a diplomatic mission in Saudi Arabia, advised U.S. Cyber Forces on diplomatic priorities, and served as U.S. ambassador to Malta.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWe need to have a diverse and talented corps of professionals in our foreign affairs agencies see more

We need to have a diverse and talented corps of professionals in our foreign affairs agencies — and in the wider development community. That matters when it comes to leadership and credibility alike.

By Aaron Williams

Peace Corps Director 2009–12

The beauty and inherent value of the Peace Corps is that it provides a different approach to America’s overseas engagement. Volunteers live in local communities, speak the national and local languages, and have great respect for the culture of the host country. Working at the grassroots level for two or more years, Peace Corps Volunteers have a unique platform for acquiring cultural agility. They have the opportunity to build relationships, to understand the priorities of the communities and organizations where they work, and to play a role in assisting these communities in reaching their goals. This connection to the people they serve is the essence of Peace Corps service, where mutual learning and understanding occurs. And the Volunteer gains the ability to be engaged in a hands-on development process.

If an individual’s career goal is to become a global citizen, then this is precisely the type of experience that will challenge you. And the Peace Corps has historically been a pathway to a career in diplomacy and development. My career certainly is an example of that. I served in the Agency for International Development USAID as a foreign service officer for 22 years as both a mission director and a senior official at headquarters. Then during the Obama administration, I had the distinct honor of serving as the Director of the Peace Corps. And I've always considered it to be a sacred trust to lead this iconic American agency. And of course, it's always been a distinct honor to represent the United States of America.

As has been well documented in congressional hearings, through extensive media coverage, and in substantial reports by foreign policy think tanks and other organizations, one thing is crystal clear: The failure to diversify senior positions in our foreign service agencies undermines U.S. credibility abroad.

As an African American, I am a direct beneficiary of the civil rights movement and stand on the shoulders of those giants who sacrificed their blood, sweat, and tears fighting for the monumental changes that opened up opportunities for Black and brown people across our country, including in the U.S. Foreign Service. Now, as has been well documented in congressional hearings, through extensive media coverage, and in substantial reports by foreign policy think tanks and other organizations, one thing is crystal clear: The failure to diversify senior positions in our foreign service agencies undermines U.S. credibility abroad. In my view, in order to pursue a robust and effective foreign policy in this ever more challenging world, we need to have a diverse and talented corps of professionals in our foreign affairs agencies.

And that’s why diversity is so important to our nation. We need to portray the true face of America, the rich diversity of our citizens. This diversity will continue to be the foundation for our nation’s progress in all aspects of our society, and a pillar of America’s role in global leadership.

Black Americans are so unrepresented historically in terms of diplomacy and international affairs that we must build a core of leaders to present the true face of America as we interact with the rest of the globe. The more diversity you bring into the C-suite of the foreign policy halls, where the highest ranking senior executives work, the bigger the cadre of people who will have a different perspective of the world and how we should interact with it.

I’ve been involved in the pursuit of diversity from the very beginning of my career, after serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Dominican Republic. I was very fortunate that my first job back in the U.S. was to serve as a minority recruiter in the first such initiative in Peace Corps history. Ever since that first job, I have been an advocate and fighter for diversity in every organization where I’ve worked. And I’ve had a career in three sectors — in government, business, and in the nonprofit world. Based on my experience, and as widely articulated by diversity and inclusion experts, the most important components for promoting diversity are to focus on several areas encompassing access, broad opportunity, retention, and career advancement.

The development community plays a prominent role as principal partners with the U.S. government in the country’s global leadership. They should invest in the diverse human capital of the future that will mirror the true face of our nation.

In my view, the principal foreign affairs agencies — the State Department, USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the Peace Corps — should focus on three areas. First, to gain a better understanding of diverse groups in our country. Second, to build effective tools and programs that include mentorships internships, sponsoring viable candidates, and the creation of a pipeline of candidates. And then thirdly, to provide opportunities for growth and promotion within these agencies.

I would hope to see, going forward, that both U.S. government agencies and, more broadly, the numerous foreign affairs organizations for the development community, as we often call it, will seize this moment to demonstrate leadership in pursuing broad-based policies and programs that will promote diversity in both the U.S. and overseas offices. The development community plays a prominent role as principal partners with the U.S. government in the country’s global leadership. And thus, they should invest in the diverse human capital of the future that will mirror the true face of our nation.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. Edited excerpts appear in the 2021 anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Aaron Williams served as a Volunteer in Dominican Republic 1967–70. He was the first African American to serve as USAID’s executive secretary, and the first African American man to direct the Peace Corps.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleWe need diverse and experienced leadership at Peace Corps — and a commitment to reimagine the agency see more

With our allies in Congress, we’re working to ensure that the administration understands this is no time to return to the status quo. We need diverse and experienced leadership at Peace Corps — and a commitment to reimagine, reshape, and retool for a changed world.

By Glenn Blumhorst

Many of us in the Peace Corps community took note of the pledge in President Biden’s inaugural address to “engage with the world once again. Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s challenges. And, we’ll lead, not merely by the example of our power, but by the power of our example.”

Those words resonate with the Peace Corps mission, not with a sense of “be like us!” but with a sense of solidarity and commitment to working and learning alongside one another, wherever we serve. One of the messages we’re driving home to members of Congress and the Executive Branch: If we’re reengaging with the world, let’s do it with ideals that are supposed to represent what’s best about this country — even as we work in our communities and at the national level to build a more perfect union.

That said, if we value the role of the Peace Corps, we have to be serious about reimagining, retooling, and reshaping the agency for a changed world. As the administration appoints new leadership for the agency, it is critical that it brings on board not only a director but top staff who reflect a commitment to equity and racial justice, and that these leaders come equipped with global experience and a deep understanding of — and commitment to — the Peace Corps community.

Equity, experience, and community

At the Peace Corps agency, January 20 marked the departure of Director Jody Olsen, who led the agency during unprecedented times, including the global evacuation of Volunteers in spring 2020. Last fall she was optimistic about Volunteers returning to the field as early as January 2021. But by December it was clear that was no longer a possibility. Plans are now for Volunteers to return in the second half of 2021. The health and safety of communities and Volunteers is paramount.

Carol Spahn has been named Acting Director of the Peace Corps. The Biden Administration has also begun to announce new political appointments. We’re meeting with Spahn and the leadership team as it takes form to ensure that we keep moving forward with the big ideas the Peace Corps community has outlined to meet the needs of a world as it is, not as it was. For Peace Corps, as with so much in this country, now is not the time to return to the status quo. Now is the time for historic changes.

When many hundreds of members of the Peace Corps community came together in summer 2020 for a series of town hall meetings and a global ideas summit, it was with a sense of an agency, a nation, and a world facing multiple crises. From those meetings came “Peace Corps Connect to the Future,” a community-driven report that brings together big ideas and targeted, actionable recommendations for the agency and the Executive Branch, Congress, and the wider Peace Corps community — particularly NPCA.

Past directors of the Peace Corps who served under Democratic and Republican administrations alike have underscored to us that the big ideas put forward here are absolutely essential.

Past directors of the Peace Corps who served under Democratic and Republican administrations alike have underscored to us that the big ideas put forward here are absolutely essential: that many of them address longstanding issues and sorely needed changes, but there never had been the opportunity to undertake them on a major scale. Now is that time.

Whom the Biden Administration appoints to top posts at the agency sends a powerful signal to the community. Will the leaders reflect a commitment to equity and racial justice — and a serious commitment to the quarter million strong Returned Peace Corps Volunteer community? Members of Congress who have been champions for Peace Corps funding are watching as well.

A roadmap for change

The report “Peace Corps Connect to the Future” provides a roadmap for change. While the report is far-ranging in point-by-point recommendations that are grouped into eight separate chapters, here are three overriding themes that emerged. We’re working to ensure that the administration and new staff at the agency take these to heart:

1. The Peace Corps community must be a leader in addressing systemic racism.

The Peace Corps agency, like American society as a whole, is grappling with how to evolve so that its work fulfills the promise of our ideals. This means tackling agency hiring and recruitment, and greater support for Volunteers who are people of color, to ensure an equitable Peace Corps experience. It also means ensuring that perceptions of a “white savior complex” and neocolonialism are not reinforced. These are criticisms leveled at much work in international development, where not all actors are bound by the kinds of ideals that are meant to guide the Peace Corps. Conversely, many in the U.S. bristle when hearing these terms; but it’s important to both recognize the context and address them head-on to enable a more effective and welcome return for Volunteers.

2. The Peace Corps agency needs to stand by its community — and leverage it for impact.

The agency’s work is only as good as the contributions of the people who make it run. This does not mean only staff but includes, in particular, the broader community of Volunteers and returned Volunteers. In programs around the world, it absolutely includes the colleagues and communities that host Volunteers. NPCA has demonstrated that it is both possible and beneficial to become community-driven to promote the goals of the Peace Corps. Community-driven programming will keep the work both current and relevant to the world around us, ensuring that the agency succeeds in its mission in a changed world.

3. Now is the moment for the Peace Corps agency to make dramatic change.

The opportunity for a reimagined and re-booted Peace Corps now exists and it should be taken.

Who is there to lead the change matters. From the Peace Corps community, this message came through clearly: When it comes to the permanent director, they should be an individual of national stature, preferably a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer, who is committed to transformational change at the agency. They must have the gravitas to advance the Peace Corps’ interests with both Congress and the White House while also making the case to the American people about the value of a renewed Peace Corps for the United States — and communities throughout the world.

In an unprecedented time, the Peace Corps community has come together with an unparalleled response. With the new administration, there are Returned Peace Corps Volunteers with years of experience already taking on key roles in the U.S. Department of State, Department of Labor, and National Security Council. These appointments show a value placed on experience and racial equity — and a commitment to leading with the best. Let’s ensure that commitment carries over to Peace Corps as well.

Glenn Blumhorst is President & CEO of National Peace Corps Association

- Dan Baker likes this.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleMeet Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, Janelle Jones, and Jalina Porter see more

First Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer for the State Department. Chief Economist for U.S. Department of Labor. And Principal Deputy Spokesperson for the State Department.

Photo: Janelle Jones

“We are at a particular time in America, and the world is watching us,” Gina Abercrombie- Winstanley said after being appointed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken to her new role. That would be the first-ever chief diversity and inclusion officer for the State Department.

In January at State, Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Jalina Porter also set precedent — when she became the first Black woman appointed as principal deputy spokesperson. Returned Volunteer Janelle Jones is breaking ground, too: She's the first Black woman to serve as chief economist for the Department of Labor.

Here's an introduction to all three.

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley

First Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer for the State Department

Oman | 1980–82

A new post and a new leader for a decades-old problem: Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley was appointed in April as the first-ever chief diversity and inclusion officer for the State Department. She is tasked with leading efforts to ensure that we nurture a diplomatic corps that truly represents this country — and looks like this country — and sheds once and for all the cliche of “pale, male, and Yale.”

This is not the first time that Abercrombie-Winstanley has led the way — and been tested. After serving with the Peace Corps in Oman, she went on to become the first woman to lead a diplomatic mission in Saudi Arabia; she was serving as consul general in Jeddah in 2004 when a suicide bomber detonated a bomb near the consulate, killing nine.

She advised U.S. Cyber Command on diplomatic priorities, and she served as U.S. ambassador to Malta. In December 2020 she gave the keynote address for Peace Corps’ Franklin Williams Awards ceremony. “We are the messengers of what Peace Corps is and can be,” she said, recounting both the opportunities she helped create and the resistance she faced as a Black woman serving in the Peace Corps and in the U.S. Foreign Service. Read more: bit.ly/we-are-peace-corps

Photo of Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley by Mandel Ngan/AP

Janelle Jones

Chief Economist for U.S. Department of Labor

Peru | 2009–11

Appointed in January, Jones is the first Black woman to serve as chief economist for the Labor Department. Her top goals: create jobs, address inequality — like the fact that the unemployment rate for Black individuals is often double that of whites — and pursue economic recovery that truly benefits everyone. One way to do that is, she says, to pursue economic policies fueled by the sensibility of “Black Women Best” — that is, those that focus on pulling Black women out of recession and into prosperity, because that will mean we’re building an economy that benefits everyone.

Previously, Jones served as an economic analyst at the Economic Policy Institute. Her research has been cited in The Washington Post, The New Yorker, The Economist, Harper’s, and The Review of Black Political Economy. She holds degrees from Spelman College and Illinois State University.

As a Peace Corps Volunteer she worked on small business development; she also served as an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer in Sacramento with a grassroots nonprofit focused on community health.

Janelle Jones photo courtesy Economic Policy Institute

Jalina Porter

Principal Deputy Spokesperson for the State Department

Cambodia | 2009–11

Appointed in January 2021 to serve as deputy spokesperson for the U.S. State Department, Porter is the first Black woman in history to serve in that role. She was formerly communications director for Congressman Cedric Richmond (D-LA), who was appointed a senior advisor to the Biden administration.

Porter is also a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a 2020 recipient of Peace Corps’ Franklin Williams Award. In her work as a strategic communications advisor, she has focused on peace and security, and diversity, equity, and inclusion. Throughout her career, she has advised and trained over 3,000 public and foreign policy professionals, veterans, artists, athletes, politicians, and leading corporate executives. She was named a 2018 top 35 Black American National Security and Foreign Policy Next Generation Leader by New America and a 2019 Foreign Policy Influencer by the Women’s Foreign Policy Group.

She is a member of the inaugural cohort of NPCA's “40 under 40” and previously served on the board of the Returned Peace Corps Volunteers of Washington, D.C. as development director. Immediatly prior to her new post, she also served on the advisory council for the community-driven report “Peace Corps Connect to the Future.” She is a proud graduate of Howard University, where she received her bachelor’s degree, and Georgetown University, where she earned her master’s. A former professional dancer, Porter is passionate about the arts, living with intention, and unique storytelling through movement and writing.

Read Jalina Porter’s interview with civil rights attorney Elaine Jones in our Winter 2021 edition. Follow her official account on Twitter at @StateDeputySpox.

Jalina Porter photo courtesy Department of State

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA global approach to community building — at home and around the world see more

Take a community-based approach to service at home and around the world. And learn from Black Americans making their mark abroad.

By Jerome Moore [as told to Jake Arce]

My interest in community development started while I was growing up in Nashville, Tennessee. It began with a volunteering organization called The Contributor, which helps homeless neighbors establish their own microbusiness and work their way into housing through selling an award-winning street paper. The work really inspired me to continue volunteering in college and discover how I can better benefit my community — especially to make an impact working against systemic oppression.

I later became interested in ways that community development and community-based projects can make an impact in the global sphere. This ambition, combined with my desire to learn a new language, is part of what motivated me to submit an application for the Peace Corps. I served in Paraguay 2015–17. It was the first time I had been outside of the country, and I can truly say that the Peace Corps has shaped my life for the better and inspired me to do the projects that I am doing today.

Peace Corps gives you a completely different perspective on what it means to be an American — and how our identity can be viewed through a global lens. And it provides a new perspective on global development and making a difference in the communities you serve.

The Peace Corps brings out a sense of vulnerability, in terms of learning a new language and being immersed in a different culture. It gives you a completely different perspective on what it means to be an American — and how our identity can be viewed through a global lens. And it provides a new perspective on global development and making a difference in the communities you serve.

I came from a lower middle class community, with many people who weren’t aware of what was going on outside of their state and did not know about opportunities related to public service. There weren’t any advertisements I saw on television, or within my community; that made it difficult to discover opportunities with Peace Corps — and public service in general. There are also so many things to worry about financially that traveling outside of the country isn’t something many would typically consider. One of the few opportunities would be the military — and that’s not something everyone would want to pursue.

It’s important to spread the message so communities across the globe know how they can contribute with public service initiatives, including the Peace Corps, to promote cohesion and character development. This is something that I’m really passionate about, and I want to spread the word about the impact you can make and the connections you can form.

I like to utilize a needs assessment to develop goals; what the community needs differs depending on the setting. Needs may be completely different in Nashville, Tennessee, in comparison to Iturbe, Paraguay. Along with the projects I’ve already undertaken, this summer I’m launching a Black Youth Abroad Curriculum that introduces Black youth to opportunities outside the United States.

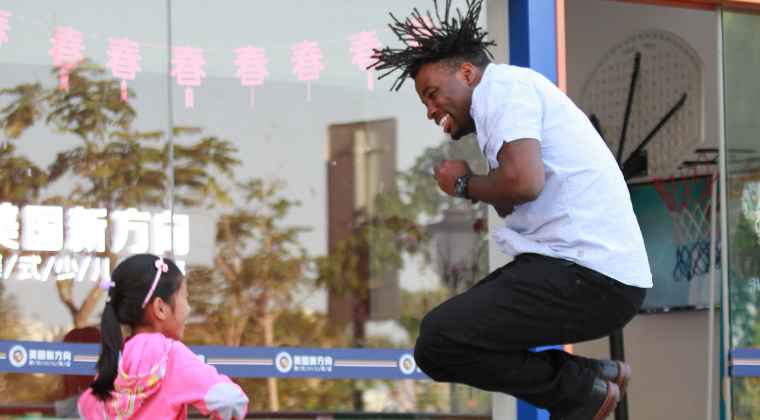

Attitude and altitude: visiting the Birds Nest project, in Xiamen, China. Photo courtesy Jerome Moore

Community Changers

Making an impact both globally and domestically has motivated me to pursue work in community building on a large scale. Several years ago I founded Community Changers, an organization to bring youth to partake in community-based initiatives—and discuss lifestyles of Black people living in the United States and abroad. We have three separate projects to fulfill our community-based goals.

COMMUNITY PROJECTS cover hands-on development work in areas around the world: Birds Nest, in Xiamen, China; The Contributor, in Nashville, Tennessee; and All African People’s Development and Empowerment Project in Huntsville, Alabama. The purpose is to add a more cool and flavorful approach to community-based projects.

DEEP DISH CONVERSATIONS is a laid-back, discussion-based video series: I sit down with people at Gino’s East Pizza to discuss social issues and how those impact their life—all over a slice of pizza. We look for relatable ways to further community development.

“BLACK AMERICANS MAKING THEIR MARK: STORIES ABROAD” is a podcast and video series where Black Americans discuss their personal experience in global settings. This has given me an opportunity to highlight serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Paraguay, and traveling to Costa Rica and China. There is often a sense that all Black people around the world deal with the same issues, but this is not true. We are the majority skin color around the world, but we all have different experiences, whether you are Black in the United States or the U.K., you’re Black in the Caribbean or on the continent of Africa. We look to highlight our specific experiences as Black Americans and address the rare cases Black Americans are shown traveling outside the United States. We hope to provide advice and motivate other Black Americans to travel abroad—through Peace Corps or through personal exploration. You can’t get that knowledge unless you leave the United States and immerse yourself in another community.

Photo courtesy of Jerome Moore

Global Black Voices: Peace Corps Edition

Jerome Moore’s podcast “Black Americans Making Their Mark: Stories Abroad” seeks to inform, inspire, and fill a void in media representation. Exploring the diversity of Black experiences around the world also means tackling misperceptions and stereotypes — and the role all of us have in reversing those. Big in the mix: Black Returned Peace Corps Volunteers. Here are pieces of three conversations.

ROB WATSON

Director of Student Programs, Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School

Peace Corps Volunteer in Paraguay 2010–13

Beginnings: “My story around service starts with my parents doing service work in different ways: my mom in a faith-based community, my stepfather as a corrections officer, and my dad went from being a community organizer to a principal to a superintendent in schools, and he worked in group homes … Peace Corps was the chance to take my conception of justice, service, education, antipoverty, and civic engagement to the international context.”

Connections: “Leaders from Afro-Paraguayan communities came in to do artistic interventions in my community in Encarnacion, in the south of Paraguay—and it was really cool: We were having exchanges with Afro-Paraguayan communities and Paraguayan communities who weren’t [Afro-Paraguayan]. Sometimes we as Volunteers facilitated exchange around Black realities to Paraguayans who weren’t familiar with it.”

Realities: “Especially in recent times, I’m seeing the Peace Corps take more of a deliberate role in thinking about issues of racial justice in the United States, the realities of Volunteers of different races — but also sexual orientations and everything in between.”

NYASSA KOLLIE

Regional Recruiter for Peace Corps

Peace Corps Volunteer in Malawi 2015–18

In Liberia, Nyassa Kollie’s parents were taught by a Peace Corps Volunteer. Now she helps others understand what service might mean for their lives.

Foundations: “My parents are Liberian immigrants and have always pushed education. That Volunteer instilled this love of education — but also the sense, ‘Hey, I can do what I set my mind to.’ What makes Peace Corps so different is that we’re an agency about relationships and people.”

Represent: “I’m a regional recruiter for the Chicagoland area, so I have the pleasure to talk about the Peace Corps all the time — with people who could be interested and people who never thought about Peace Corps … They say every recruiter is a diversity recruiter. On top of that, we have nationwide diversity recruiters who specifically target HBCUs or predominantly Asian institutions … We want our Volunteers to reflect the United States. Returned Volunteers need to feel more emboldened to share their story, because you go back to your hometown and talk to people you know, who can say, ‘Jerome graduated from here and this is something I want to do.’”

TIM CAMPBELL

Graduate Student, University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service; Member, Task Force to Advance the State of Law Enforcement in Arkansas

Peace Corps Volunteer in The Gambia 2016–18

A native of Little Rock, Campbell was the first person in his family to graduate from college. In summer 2020 he led peaceful protests against the killing of George Floyd and other Black Americans and convened meetings with the governor to discuss community policing and training manuals. In June he was appointed to a task force to reform policing.

Why Commit: “[Peace Corps] is not something you’re doing just for some benefit, this is something you do because you want to … I would tell anybody to be a product of your decisions and not your circumstances, be a product of your wisdom and not your ignorance, be a part of your positivity and not your proximity.”

Read, listen, explore: jeromelmoore.com

Jake Arce is a graduate student in the School of International Service at American University. He picked up work on this story begun by Del Wood, who studies at University of Southern California.

-

Jonathan Pearson posted an articleAddressing systemic racism begins with us see more

Work with NPCA on this crucial issue — and have an impact on the wider Peace Corps community.

In our work to lead a vibrant Peace Corps community, National Peace Corps Association is looking for a partner with expertise in providing training on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Our society needs to tackle systemic racism as it has shaped institutions and communities — including the Peace Corps community. And addressing systemic racism begins with us.

Here is a request for proposals to work with NPCA in this crucial area — and, through the work we do with the broader Peace Corps community, make a valuable contribution in this area more broadly.

Those specializing in building an anti-racism environment within member-based nonprofit organizations are particularly encouraged to submit proposals. For questions please contact NPCA by email.

Please review our Frequently Asked Questions regarding this request for proposals.

Submissions will be accepted through Friday, February 26, 2021 at 6 p.m. EST.

SPECIAL NOTE: Submission deadline has been extended to Friday, March 5, 2021 at 6 p.m. EST.

-

Ana Victoria Cruz posted an articleKeynote address by Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley at the Franklin H. Williams Award Ceremony see more

In a keynote address for the Franklin H. Williams Award ceremony, Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley recounts the opportunities she helped create — and the resistances she faced — as an African American woman serving in the Peace Corps and in the U.S. Foreign Service.

By Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley

On December 15, 2020, the Peace Corps recognized six leaders in the Peace Corps community — and a civic leader with a shared commitment to Peace Corps values — with the Franklin H. Williams Award. The keynote address was delivered by Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, whose pathbreaking career in the Foreign Service has created new opportunities and possibilities for women and minorities. Abercrombie-Winstanley served with the Peace Corps in Oman, was the first woman to lead a diplomatic mission in Saudi Arabia, advised U.S. Cyber Forces on diplomatic priorities, and served as U.S. ambassador to Malta. Meet this year’s winners and read Ambassador's Abercrombie-Winstanley remarks below.

I am so jazzed to be here with you. I asked what I should be aiming to leave you with today, but having seen the backgrounds of these nominees, I know we all will be leaving here today brimming with awe and inspiration.

I’m often asked how I got interested in public service and foreign policy, and I suspect my beginnings are similar to yours. I had parents, teachers and mentors, like you, who opened my eyes to the wider world. And they helped me understand that I could have a meaningful role in it. They advocated volunteerism and servant leadership — and they practiced what they preached. These people, and more, instilled in me a commitment to service. A commitment to what we now call “paying it forward.” That commitment is what Peace Corps stands for.

Now, I raised eyebrows when I said I wanted to join Peace Corps. My mother was a little nervous about me going “over there.” My father asked me if I was going off to learn how to be poor, instead of getting a job to pay off my school loans. Our family’s international experience, until then, was largely confined to stints in the military. It’s a unique experience for many Americans — and especially so for Volunteers of color.

I remember the excitement about leaving home, the worry about fitting in, of learning how to do the job properly so I could accomplish what we all want to do — make lives better. Asked to describe what came to my mind when I remember my Peace Corps experience, I said a combination of frustration and pride. Frustration because some of my trainers wondered whether I was a good “fit.” Pride because I got the highest language score of my entire group. Frustration because of the occasional chauvinism from my host-country boss, and pride when a health worker confidently displayed the new vaccine storage techniques I had taught the previous month. As we all wait for a COVID vaccine, that is an especially strong memory.

I know what it feels like to be far from home and have people look at you quizzically when you explain you’re the American Peace Corps Volunteer. And we all know that feeling when interest starts fading in the eyes of your auntie ’cause you talked about your village experience just a little too long.

Many Volunteers can tell horror stories about the “stomach bug” diet, while others like me, bring back the local cuisine attached to our bodies! But what we also bring back are experiences that will serve us well in every aspect of life. My Peace Corps experiences have been a part of everything I have accomplished since.

Peace Corps provided the solid foundation that allowed me to work my way up in the U. S. diplomatic corps to serve our nation as President Obama’s personal representative. Our nominees used their own experiences to become shining examples of servant leadership.

Peace Corps provided the solid foundation that allowed me to work my way up in the U.S. diplomatic corps to serve our nation as President Obama’s personal representative. Our nominees used their own experiences to become shining examples of servant leadership.

Peace Corps teaches resilience. In your personal relationships, in your work, and in yourself. So today, as I share a bit of my journey, I hope that I remind you of the possibilities of your own.

Peace Corps honed my language skills, and improved my interpersonal skills. Presented with the etiquette demands of communal eating, an uncomfortable style of restroom, or a wedding that begins at 2:00 AM? No problem. I had been there and done that as a Volunteer — and navigated all of these challenges smoothly as a diplomat. The little victories are sweet and lead the way to larger personal connections.