Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleHonoring global leaders in the Peace Corps community from Senegal, the Philippines, and the U.S. see more

Every five years, Peace Corps presents the John F. Kennedy Service Awards to honor members of the Peace Corps network whose contributions go above and beyond for the agency and America every day. Here are the 2022 Awardees.

By NPCA Staff

Photo: Dr. Mamadou Diaw, Peace Corps staff recipient of the 2022 JFK Service Award. Photos Courtesy of the Peace CorpsOn May 19, at a ceremony at the U.S. Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C., the Peace Corps presented The John F. Kennedy Service Awards for 2022. Every five years, the Peace Corps presents the JFK Service Award to recognize members from the Peace Corps community whose contributions go above and beyond their duties to the agency and the nation. The ceremony as also live-streamed around the world — since this is a truly global award, with honorees from Senegal, the Philippines, and the United States.

Join us in congratulating this year’s awardees for tirelessly embodying the spirit of service to help advance world peace and friendship: Liz Fanning (Morocco 1993–95), Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse (PCV: Guinea 2006–07, Zambia 2007–08; Response: Guyana 2008–09, and Uganda 2015–16), Karla Sierra (PCV: Panama 2010–12; Response: Panama 2012–13), Dr. Mamadou Diaw (Peace Corps Senegal 1993–2019), Roberto M. Yangco (Peace Corps Philippines 2002–Present).

RETURNED PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEER

Liz Fanning | Morocco 1993–95

Liz Fanning is the Founder and Executive Director of CorpsAfrica, which she launched in 2011 to give emerging leaders in Africa the same opportunities she had to learn, grow, and make an impact. Fanning has worked for a wide range of nonprofit organizations during her career, including the American Civil Liberties Union, Schoolhouse Supplies, and the Near East Foundation. She received a bachelor’s in economics and history from Boston University and a master’s in public administration from NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. She received the Sargent Shriver Award for Distinguished Humanitarian Service from National Peace Corps Association in 2019 and a 2021 AARP Purpose Prize Award.

RETURNED PEACE CORPS RESPONSE VOLUNTEERS

Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse, DNP, RN | Guinea 2006–07, Zambia 2007–08, Response: Guyana 2008–09, Response: Uganda 2015–16

Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse grew up in the Philippines, then emigrated to the United States in 1997. She pursued a career at the intersection of nursing, public service, and volunteerism, earning her doctor of nursing practice in 2020 — while continuing to serve as a full-time school nurse for the San Francisco Unified School District. As a compassionate, socially conscious nurse dedicated to providing care and developing nurse education, Evenhouse has a keen affinity for teaching, community service, and cultural exchange that led her to serve in four countries — Guinea, Zambia, Guyana, and Uganda — as a Volunteer and Peace Corps Response Volunteer. She also volunteered at two health offices in the Philippines as a public health nurse as well as the Women’s Community Clinic in San Francisco as a clinician.

Karla Y. Sierra, MBA | Panama 2010–12, Response: Panama 2012–13

Karla Yvette Sierra was born in El Paso, Texas, to Mexican American parents. Sierra graduated from Colorado Christian University with a bachelor’s in business administration and a minor in computer information systems. Elected by her peers and professors, Sierra was appointed to serve as the Chi Beta Sigma president as well as the secretary for the student government association. Sierra volunteered with Westside Ministries as a youth counselor in inner city Denver. Shortly after completing her Master of Business Administration at the University of Texas at El Paso, she started working for Media News Group’s El Paso Times before being promoted to The Gazette in Colorado. Sierra served as a Volunteer in Panama for three years as a community economic development consultant focused on efforts to reduce poverty, increase awareness of HIV and AIDS, and assist in the implementation of sustainable projects that would benefit her Panamanian counterparts. Her Peace Corps experience serving the Hispanic community fuels her on-going work and civic engagement with Hispanic communities in the United States.

PEACE CORPS STAFF

Dr. Mamadou Diaw | Peace Corps Senegal 1993–2019

Dr. Mamadou Diaw — born in Dakar — is a Senegalese citizen. He studied abroad and graduated in forestry sciences and natural resource management from the University of Florence and the Overseas Agronomic Institute of Florence. He joined the Peace Corps in 1983 as Associate Peace Corps Director (APCD) for Natural Resource Management. In that capacity, he managed agroforestry, environmental education, park and wildlife, and ecotourism projects. From 1996 to 2001, he served as the coordinator of the USAID funded Community Training Center Program. In 2008, he switched sectors, becoming Senior APCD Health and Environmental Education. He received a master’s degree in environmental health in 2014 from the University of Versailles, and a doctorate in community health from the University of Paris Saclay, at the age of 62. Dr. Diaw coached more than 1,000 Volunteers and several APCDs from the Africa region, notably supporting Peace Corps initiatives in the field of malaria and maternal and child health. He retired from Peace Corps toward the end of 2019 and is currently working as an independent consultant.

Roberto M. Yangco (“Ambet”) | Peace Corps Philippines 2002–present

Ambet Yangco, a social worker by training, started his career as an HIV/AIDS outreach worker for Children’s Laboratory Foundation. He then served as a street educator in a shelter for street children and worked for World Vision as a community development officer. Twenty years ago, Yangco joined Peace Corps Philippines as a youth sector technical trainer. It wasn’t long before he moved up to regional program manager; then sector manager for Peace Corps’ Community, Youth, and Family Program; and now associate director for programming and training during the pandemic.

READ MORE and SEE PHOTOS from the 2022 JFK Awards ceremony here.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleOne year after evacuation from the Philippines: A Peace Corps Volunteer on the trauma of leaving see more

One year after being evacuated from the Philippines, a Peace Corps Volunteer faces the trauma of leaving, the country he returned to, and a question that’s impossible to answer.

By Rok Locksley

Work and friendship: Rok Locksley, left, with Ban-Ban Nicolas. Photo courtesy Rok Locksley

The last day of my Peace Corps service was Friday, March 13, 2020. Together with my wife, Genevieve, I was serving in the Peace Corps in the Philippines. We had gotten up early to enjoy the sunrise on what we knew would be our last day on the island that had become our home.

My counterpart was Ban-Ban Nicolas, with whom I was collaborating on marine conservation efforts on an island near Cebu. I called him Ban2x. And over the course of service, we developed a deep friendship.

Ban2x arrived at our host family’s house early in the morning in his family car. He would shuttle us to the seaport. Airports had already shuttered. He knew we were on the last boat off the island, and he wanted to make sure we got to the port safely.

We loaded our bags into his car, and he promised to look after our things, to check in on our dogs and our house. At this point we thought we were just being consolidated: all Volunteers gathered together temporarily. On the drive, Ban2x and I made promises to keep each other updated and what the estimates were for returning after consolidation — we were speaking in that awkward way that you do when you have so much you want to say but lack the words or ability to properly express how much you value the other person.

As I made my way onto the bridge to the boat that would carry me literally and figuratively out to sea, I turned for one last look at my friend and said, “It’s not goodbye, just until we see each other again.”

We got out of the car and I could see tears welling up in his eyes. I could feel them in mine. We lingered until the last possible minute. As I made my way onto the bridge to the boat that would carry me literally and figuratively out to sea, I turned for one last look at my friend and said, “It’s not goodbye, just until we see each other again.”

I got on the boat, found a seat, and sat down gingerly. Everything was moving in a surreal way. At first I thought it was the rocking waves, but then I started to feel my world crashing around me. There was everything we had left behind: our project, our year-old dogs who had cried and tried to squirm under the fence to get in the car as we drove away. My host family, with tears in their eyes. My coworkers, their faces grimaced in shock when I told them the day before that I had to leave.

I began the journey back to the United States, but I would not be returning home. My home was in the Philippines.

Where do we go from here? Photo by Rok Locksley

At sea

The boat carried us to a larger island where we met up with other Peace Corps Volunteers. We managed to catch the last boat off of that island, and we sat there on the top deck of a ferry, rocking in the sea, surrounded by tourists trying to figure out if they should stay or go. As for us 30 Volunteers, we were shell-shocked and broken, leaving through no choice of our own. We didn’t really talk. What was there to say?

About two hours into the five-hour ferry trip, our phones chirped and pinged and vibrated at the same time with an alert. It was an ominous sound, and it carried a message that changed our lives. The director of the Peace Corps had declared the evacuation of all Volunteers. That is how we found out that our service was over: On a boat, rocking in the sea, carrying what random items we had shoved into our backpacks in a state of trauma. Some of us cried. Some tried to call their families. Some stared off across the waves, trying to soak up the last of the Philippines. Most, like me, were simply in shock. And desperately trying to figure out what to do next.

Back in the States, we could not go to my parents’ house or my wife’s parents’ house, because of COVID-19. I knew that the evacuation route would take us through numerous airports, and I was sure I was getting exposed. The risk was not worth it to my family; health and age put them in the at-risk population. My grandparents’ house was out. My uncles and aunts had young kids. We literally had nowhere to go.

I timidly reached out to a few people, inquiring about whether it might perhaps be possible maybe that … They made it clear, gently but firmly, that they did not want to risk the fact that I might be bringing the virus, especially coming from Southeast Asia. I understood.

We had given up ties in the States to join the Peace Corps. We had no house, no car, no job waiting. All that was waiting for us stateside: the terrifying horror of the unknown. Unknown if we had the virus. Unknown where we would sleep when we landed. Unknown where we could get health care or insurance or a job or food or winter clothes. Aside from what we carried, what possessions we owned were in a storage unit. And I was not sure how I was going to make the next payment on that.

As I was making calls from the boat and, later, from a hotel, trying to figure out where exactly we should attempt to fly to in the United States, a fellow Volunteer overheard my struggle. His family had a summer cabin in the Midwest. It wasn’t summer. But he offered it as a place of landing to us and a few other evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers for the mandatory two-week quarantine. We had no option other than the Peace Corps reimbursement for staying in a hotel. We gratefully chose the EPCV cabin.

The Facebook group for evacuated Volunteers was one of the few places we didn’t have to explain to others why this transition was so difficult, why we all felt lost at sea.

We ended up living there in quarantine from March until June. Three months of trying to make sense of what had happened — and was still happening around us. Three months of sleepless nights and tearful mornings. Three months of confusion, loss, and desperation. Three months of writing resumes and filling out applications. Three months of Zoom interviews and those awful hopes that come with searching for a job: of failing again and again. Three months of struggling alongside my fellow evacuees to find our new place in the pandemic world. Three months of every other American dealing with a new world and none of them understanding what had happened to us. The Facebook EPCV group was one of the few places we didn’t have to explain to others why this transition was so difficult, why we all felt lost at sea.

I talked to Ban2x at least once a week. That helped a bit. In the EPCV cabin, we shared our struggles with one another and tried to help others as best we could. Mostly we sat staring into space, thinking about all that had been ripped away — and what we were supposed to do next. I cannot imagine what it was like for Volunteers who had chosen the lonely hotel room for mandatory quarantine.

After three months, with the warmth of summer finally arriving, there was a changing of our seasons, too: We started to get hired or accepted into graduate school. I was fortunate to receive a Peace Corps Fellowship. Some of us got federal jobs, thanks to non-completive eligibility that comes with status as a returned Volunteer. Without the support of the RPCV network, National Peace Corps Association’s meetings and seminars, and Jodi Hammer’s counsel and advice through the Global Reentry Program, I don’t think any of us would have made a good transition out of that cabin.

This is water. Photo courtesy Rok Locksley

The problem with that question

I have recently had a few Returned Peace Corps Volunteers ask me what the hardest part about the evacuation was. The problem with the question is its premise; it makes it seem like the evacuation is over. For me it is not.

I am building a place that is starting to feel like home again in Illinois. And we did manage to get one of our dogs to the States in the fall. (The rest were poisoned, we found out later). I have school to focus on, but the evacuation is not an easily packaged life event. It was trauma and I am still experiencing it, working through it, processing it.

Every time I talk to Ban2x, I am filled with conflict about abandoning my work and my friends. I question whether I should have stayed on my island — which has had fewer cases than my neighborhood here in Illinois. Did we make the right choice to return to the United States? I still find myself trying to discern a morally correct answer to this question.

The reason that we have adopted the signifier EPCVs rather RPCVs is because we all came back at the same time to a nightmare version of America that was nothing like what we had left. This was not the place often dreamed of in our desperate moments of homesickness. This was a foreign land to us. The restaurants closed, the markets eerily empty, wide eyes of fear peeking over new masks — and other faces with self-assured smirks.

There is also this strange aspect to coming back with more than 5,000 other Americans: The people I was competing with for jobs were my friends and fellow EPCVs. The person’s spot I took for my graduate program was a fellow evacuee. For every one of us who got a federal job or fellowship, that meant another EPCV did not. I don’t mean that in the abstract. I mean it literally. We would have Zoom meetings with members of our cohort and find out we were all in the final round for the same job. Only one of us could get it.

I had previously met a few people who had lost their homes due to fire or other circumstances beyond their control. People who have walked out of a strange airport in a strange land without any idea of what to do next — but carrying a hope that life would get better. People who have relied on the charity and goodwill of others to survive. A year later these experiences are much less hypothetical and much more real. It helps me to understand their situation and seek out guidance from them.

Today, on the year anniversary of our evacuation, I had a conversation with my counterpart and best friend, Ban2x. Over the past year, we have kept in contact every week, updating each other on our lives, hopes, and dreams — all the while following up on the final steps of our project, which is finally almost at fruition. Ban2x and his wife go for regular rides on the bicycles that we left behind. They send photos over Messenger of their rides and adventures to some of our favorite spots. I get photos of gatherings in the community, and it is awesome to see folks in my community wearing clothes we left behind and using the items that didn’t make it into our suitcases in that frantic final morning packing session. A few months ago, Ban2x tried to send some of the more precious items to us, but international shipping costs during the pandemic made it effectively prohibitive. They were handed out or given away to our friends and co-workers.

The hardest part is that we are still going through it. Some of us are still waiting to return to service.

When we talk, Ban2x and I, each of us is searching for words trying to fill in those things are that are still left unsaid. We wonder when this will end, and what the world will look like when it does. He stays healthy and, because of the island’s precautions, the pandemic is less of a threat there than I feel here with my mandatory in-person classes. We plan for the theoretical reunion that might take place in the next few years. I talk about all the spots and things I want to share with him in America. He tells me about the changes in our community and celebrations I have missed. Ban2x, always the optimist, smiles and says things that would translate to something along the lines of “When the time is right” or “When fortune favors us.”

We laugh a bit more in recent weeks, but sometimes my laughs are a bit hollow. I know that I can’t just jump on a plane and visit anytime I want. And I can’t bring him here for a visit. I know it will be a few years before restrictions are lifted enough to allow us to visit our home again. Until then, despite the temporary roof over my head, my heart still feels homeless. I still feel like I am adrift on the sea, packed in with all the other EPCVs rocking in a boat with no port, and wondering what happens next.

That is what it is like to have been evacuated during the pandemic. Generally, my experience is too much go through just to answer the question “What was the hardest part?” The gap is too wide. The cut is still too deep. And although it is healing, it is a long way from being a faded memory.

Maybe the closest I can come to answering my fellow RPCVs’ questions about evacuation is this: The hardest part is that we are still going through it. Some of us are still waiting to return to service.

SHARE YOUR STORY

Are you a Volunteer who was evacuated because of COVID-19? Are you part of the Peace Corps community with a story to tell? Let us know: worldview@peacecorpsconnect.org.

READ MORE

Rok Locksley’s tribute to Ban2x in WorldView magazine, and evacuation stories of dozens of Peace Corps Volunteers from around the world.

“How can we transform this moment in Peace Corps history?” Rok Locksley takes part in a discussion with other evacuated Volunteers as part of the Global Ideas Summit Peace Corps Connect to the Future.

Rok Locksley served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Republic of Moldova from 2005–08. He then worked as a Recruiter for Peace Corps 2009–16 and went back for a second tour with his partner, Genevieve, in the Philippines 2018–20. Locksley is currently a Peace Corps Fellow at Western Illinois University. He intends to return to his island at the first possible opportunity.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAsian American and Pacific Islander leaders have a conversation on Peace Corps, race, and more. see more

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity. A conversation convened as Part of Peace Corps Connect 2021.

Image by Shutterstock

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are currently the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S., but the story of the U.S. AAPI population dates back decades — and is often overlooked. As the community faces an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes and the widening income gap between the wealthiest and poorest, their role in politics and social justice is increasingly important.

The AAPI story is also complex — 22 million Asian Americans trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent, each with unique histories, cultures, languages, and other characteristics. Their unique perspectives and experiences have also played critical roles in American diplomacy across the globe.

For Peace Corps Connect 2021, we brought together three women who have served or are serving as political leaders to talk with returned Volunteer Mary Owen-Thomas. Below are edited excerpts from their conversation on September 23, 2021. Watch the entire conversation here.

Rep. Grace Meng

Member, U.S. House of Representatives, representing New York’s sixth district — the first Asian American to represent her state in Congress.

Julia Chang Bloch

Former U.S. ambassador to Nepal — the first Asian American to serve as a U.S. ambassador to any country. Founder and president of U.S.-China Education Trust. Peace Corps Volunteer in Malaysia (1964–66).

Elaine Chao

Former Director of the Peace Corps (1991–92). Former Secretary of Labor — the first Asian American to hold a cabinet-level post. Former Secretary of Transportation.

Moderated by Mary Owen-Thomas

Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines (2005–06) and secretary of the NPCA Board of Directors.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. This is not a recent story — and it’s often overlooked. I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines, and I happen to be Filipino American.

During my service, people would say, “Oh, we didn’t get a real American.” I used to think, I’m from Detroit! I’m curious if you’ve ever encountered this in your international work.

Julia Chang Bloch: With the Peace Corps, I was sent to Borneo, in Sabah, Malaysia. I was a teacher at a Chinese middle school that had been a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. The day I arrived on campus, there was a hush in the audience. I don’t speak Cantonese, but I could understand a bit, and I heard: “Why did they send us a Japanese?” I did not know the school had been a prisoner of war camp. They introduced me. I said a few words in English, then a few words in Mandarin. And they said, “Oh, she’s Chinese.”

I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised me I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.”

In Nepal, where I was ambassador, when I arrived and met the Chinese ambassador, he said, “Ah, China now has two of us.” I said, “There’s a twist, however. I am a Chinese American.” He laughed, and we became friends thereafter. On one of my trips into the western regions, where there were a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers and very poor villages, I was welcomed lavishly by one village. I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.” He said to her, “There she is.” “Oh, no,” she said. “She is not the American ambassador. She’s Nepali.”

Those are examples of why AAPI representation in foreign affairs is important. We should look like America, abroad, in our embassies. We can show the world that we are in fact diverse and rich culturally.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Secretary Chao, at the Labor Department you launched the annual Asian Pacific American Federal Career Advancement Summit, and the annual Opportunity Conference. The department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics began reporting the employment data on Asians in America as a distinct category — a first. You ensured that labor law materials were translated into multiple languages, including Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean. Talk about how those came about.

Elaine Chao: Many of us have commented about the lack of diversity in top management, even in the federal government. There seems to be a bamboo ceiling — Asian Americans not breaking into the executive suite. I started the Asian Pacific American Federal Advancement Forum to equip, train, prepare Asian Americans to go into senior ranks of the federal government.

The Opportunity Conference was for communities of color, people who have traditionally been underserved in the federal government, in the federal procurement areas. Thirdly, in 2003 we finally broke out Asians and Asian American unemployment numbers for the first time. That’s how we know Asian Americans have the lowest unemployment rate. Labor laws are complicated, so we started a process translating labor laws into Asian, East Asian, and South Asian languages, so that people would understand their obligations to protect the workforce.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized.

Grace Meng: I am not a Peace Corps Volunteer, but I am honored to be here. My former legislative director, Helen Beaudreau (Georgia 2004–06, The Philippines 2010–11), is a twice-Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. I am incredibly grateful for all of your service to our country, and literally representing America at every corner of the globe.

I was born and raised here. This past year and a half has been a wake-up call for our community. Asian Americans have been discriminated against long before — starting with legislation that Congress passed, like the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Japanese American citizens being put in internment camps. We have too often been viewed as outsiders or foreigners.

I live in Queens, New York, one of the most diverse counties in the country, and still have experiences where people ask where I learned to speak English so well, or where am I really from. When I was elected to the state legislature, some of us were watching the news — a group of people fighting. One colleague turned to me and said, “Well, Grace knows karate, I’m sure she can save us.”

By the way, I don’t know karate.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized. I didn’t necessarily come to Congress just to represent the AAPI community. But there are many tables we’re sitting at, where if we did not speak up for the AAPI community, no one else would.

At the root of hate

Julia Chang Bloch: I believe at the root of this anti-Asian hate is ignorance about the AAPI community. It’s a consequence of the exclusion, erasure, and invisibility of Asian Americans in K–12 school curricula. We need to increase education about the history of anti-Asian racism, as well as contributions of Asian Americans to society. Representative Meng, you should talk about your legislation.

Grace Meng: My first legislation, when I was in the state legislature, was to work on getting Lunar New Year and Eid on public school holidays in New York City. When I was in elementary school, we got off for Rosh Hashanah; don’t get me wrong, I was thrilled to have two days off. But I had to go to school on Lunar New Year. I thought that was incredibly unfair in a city like New York. Ultimately, it changed through our mayor.

In textbooks, maybe there was a paragraph or two about how Asian Americans fit into our American history. There wasn’t much. One of my goals is to ensure that Asian American students recognize in ways that I didn’t that they are just as American as anyone else. I used to be embarrassed about my parents working in a restaurant, or that they didn’t dress like the other parents.

Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Julia Chang Bloch: I wonder about data collection. We’re categorized as AAPI — all lumped together. And data, I believe, is collected that way at the national, state, and local levels. Is there some way to disaggregate this data collection and recognize the differences?

Elaine Chao: A very good question. Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Two obstacles stand in the way. One is resources. Unless there is thinking about how to do this in a systemic, long-term fashion, getting resources is difficult; these are expensive undertakings. Two, there’s sometimes political resistance. Pew Charitable Trust, in 2012, did an excellent job: the first major demographic study on the Asian American population in the United States. But we’re coming up on 10 years. That needs to be revisited.

Role models vs. stereotypes

Elaine Chao: Ambassador Julia Chang Bloch and Pauline Tsui started the organization Chinese American Women. I remember coming to Washington as a young pup and seeing these fantastic, empowering women. They blazed so many trails. They gave voice to Asian American women.

I come from a family of six daughters. I credit my parents for empowering their daughters from an early age. They told us that if you work hard, you can do whatever you want to do. We’ve got to offer more inspiration and be more supportive.

Julia Chang Bloch: Pauline Tsui has unfortunately passed away. She had a foundation, which gave us support to establish a series on Asian women trailblazers. Our inaugural program featured Secretary Chao and Representative Judy Chu, because it was about government and service. Our next one is focused on higher education. Our third will be on journalism.

I want, however, to leave you with this thought. The Page Act of 1875 barred women from China, Japan, and all other Asian countries from entering the United States. Why? Because the thought was they brought prostitution. The stereotyping of Asian women has been insidious and harmful to our achieving positions of authority and leadership. That’s led also to horrible stereotypes that have exoticized and sexualized Asian women. Think about the women who were killed in Atlanta.

That intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something we need to continue to combat.

Grace Meng: There was the automatic assumption, in the beginning, that they were sex workers — these stereotypes were being circulated. I had the opportunity with some of my colleagues to go to Atlanta and meet some of the victims’ families, to hear their stories. That really gave me a wake-up call. I talked about my own upbringing for the first time.

I remember when my parents, who worked in a restaurant, came to school, and they were dressed like they worked in a restaurant. I was too embarrassed to say hello. Being in Atlanta, talking to those families, made me realize the sacrifices that Asian American women at all levels have faced so that we could have the opportunity to be educated here, to get jobs, to serve our country. And that intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something that we need to continue to combat.

Julia Chang Bloch: We’ve talked about the sexualized, exoticized, and objectified stereotype — the Suzie Wongs and the Madame Butterflys. However, those of us here today, I think would fall into another category: the “dragon lady” stereotype. Any Asian woman of authority is classified as a dragon lady — a derogatory stereotype. Women who are powerful, but also deceitful and manipulating and cruel. Today it’s women who are authoritative and powerful.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Growing up, I was sort of embarrassed of my mom’s thick Filipino accent; she was embarrassed of it, too. I was embarrassed of the food she would send me to school with — rice, mung beans, egg rolls, and fish sauce. And people would ask, “What is that?” Talk about how your self-identity has evolved — and how you view family.

You do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Grace Meng: I don’t know if it’s related to being Asian, but I was super shy as a child. And there weren’t a lot of Asians around me. I was the type who would tremble if a teacher called on me; I would try to disappear into the walls. When I meet people who knew me in school, they say, “I cannot believe you’re in politics.”

What gave me strength was getting involved in the community, seeing as a student in high school, college, and law school that I could help people around me. After law school I started a nonprofit with some friends. We had senior citizens come in with their mail once a week, and we would help them read it. It wasn’t rocket science at all.

I tell that story to young people, because you do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Julia Chang Bloch: At some point, in most Asian American young people’s lives, you ask yourself whether you are Chinese or American — or, Mary, in your case, whether you’re Filipino or American.

I asked myself that question one year after I arrived in San Francisco from China. I was 10. I entered a forensic contest to speak on being a marginalized citizen. I won the contest, but I didn’t have the answer. At university, I found Chinese student associations I thought would be my answer to my identity. But I did not find myself fitting into the American-born Chinese groups — ABCs — or those fresh off the boat, FOBs. Increasingly, my circle of friends became predominantly white. I perceived the powerlessness of the Chinese in America. I realized that only mainstreaming would make me be able to make a difference in America.

After graduation, I joined the Peace Corps, to pursue my roots and to make a difference in the world. Teaching English at a Chinese middle school gave me the opportunity to find out once and for all whether I was Chinese or American. I think you know the answer.

My ambassadorship made me a Chinese American who straddles the East and the West. And having been a Peace Corps Volunteer, I have always believed that it was my obligation to bring China home to America, and vice versa. And that’s what I’ve been doing with the U.S.-China Education Trust since 1998.

We should say representation matters. Peace Corps matters, too.

WATCH THE ENTIRE CONVERSATION here: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity

These edited remarks appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022. -

Steven Saum posted an articleFounder and U.S. executive director of Global Seed Savers see more

Global Seed Savers has trained more than 5,000 Filipino farmers in seed saving, established three seed libraries, and is building a movement across the country to restore the traditional practice of saving seed and building seed sovereignty.

By NPCA Staff

National Peace Corps Association (NPCA) is pleased to announce the winner of the 2021 Sargent Shriver Award for Distinguished Humanitarian Service: Sherry Manning.

The Shriver Award is presented annually by NPCA to Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who continue to make a sustained and distinguished contribution to humanitarian causes at home or abroad, or who are innovative social entrepreneurs who bring about significant long-term change. The award is named in honor of the first Peace Corps Director, Sargent Shriver, whose energy and commitment were instrumental in the launch of the Peace Corps.

Sherry Manning is the founder and U.S. executive director of Global Seed Savers, an international nongovernmental organization committed to building hunger free and healthy communities with access to farmer produced seeds and food. Global Seed Savers has trained more than 5,000 Filipino farmers in seed saving, established three seed libraries, and is building a movement across the country to restore the traditional practice of saving seed and building seed sovereignty.

Sherry Manning’s work in the Philippines began 15 years ago, in 2006, when she served as Peace Corps Volunteer in the town of Tublay in Benguet Province. Global Seed Savers’ work has grown exponentially since this time; however the foundation of her story in the Philippines and continued work will always be about deep relationships to the land, people, and places of her second home, the Philippines.

Photo courtesy Global Seed Savers

The award was presented on September 24 at Peace Corps Connect, a 60th anniversary conference for the Peace Corps community. Announcing the award was Teddy Shriver, who served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Peru 2011–13 and is deputy director of Best Buddies International — and grandson of Sargent Shriver.

Connections and relationships: people, the land, seeds

“So much has happened, evolved, and grown since my days as a PCV 15 years ago in Tublay, Benguet,” Sherry Manning says. “But one thing has remained the center point of our on-going work at Global Seed Savers: authentic, deep, and meaningful connections and relationships to people, the land, seed, and our collective sustenance!”

In her acceptance speech, Manning noted: “It takes many hands and hearts for our work to flourish and it is an honor to be building this organization with our dedicated and growing team of local Filipino leadership, our boards, our community partners, and most importantly the resilient and passionate FARMERS we learn from and work side by side with to build a more food and seed sovereign world! This Award is for them and their tireless work to feed their families and communities despite tremendous struggles!”

Photo courtesy Global Seed Savers

Sherry Manning holds a master’s in environmental and natural resource law from the University of Denver Sturm College of Law and a B.A. in government from the University of Redlands in Southern California. Sherry is also a daughter, sister, and very proud auntie or Anta (as her nearly 6-year-old nephew calls her)! She has always been passionate about ending injustices, spending quality time in the natural places she advocates for, and building deep and meaningful relationships within her community. When not working for Global Seed Savers and serving on various nonprofit boards, Sherry can be found playing in the beautiful Colorado Mountains hiking, fly fishing, camping, and more.

Nominations for the Sargent Shriver Award for Distinguished Humanitarian Service are accepted year-round. To nominate an individual, please download the Shriver Award nomination packet, and submit all nomination materials to vp@peacecorpsconnect.org.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleBuilding environmentally and economically sustainable projects see more

Hilliard Hicks

Peace Corps Volunteer in South Africa (2014–16) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in the Philippines (2019–20)

By Hilliard Hicks

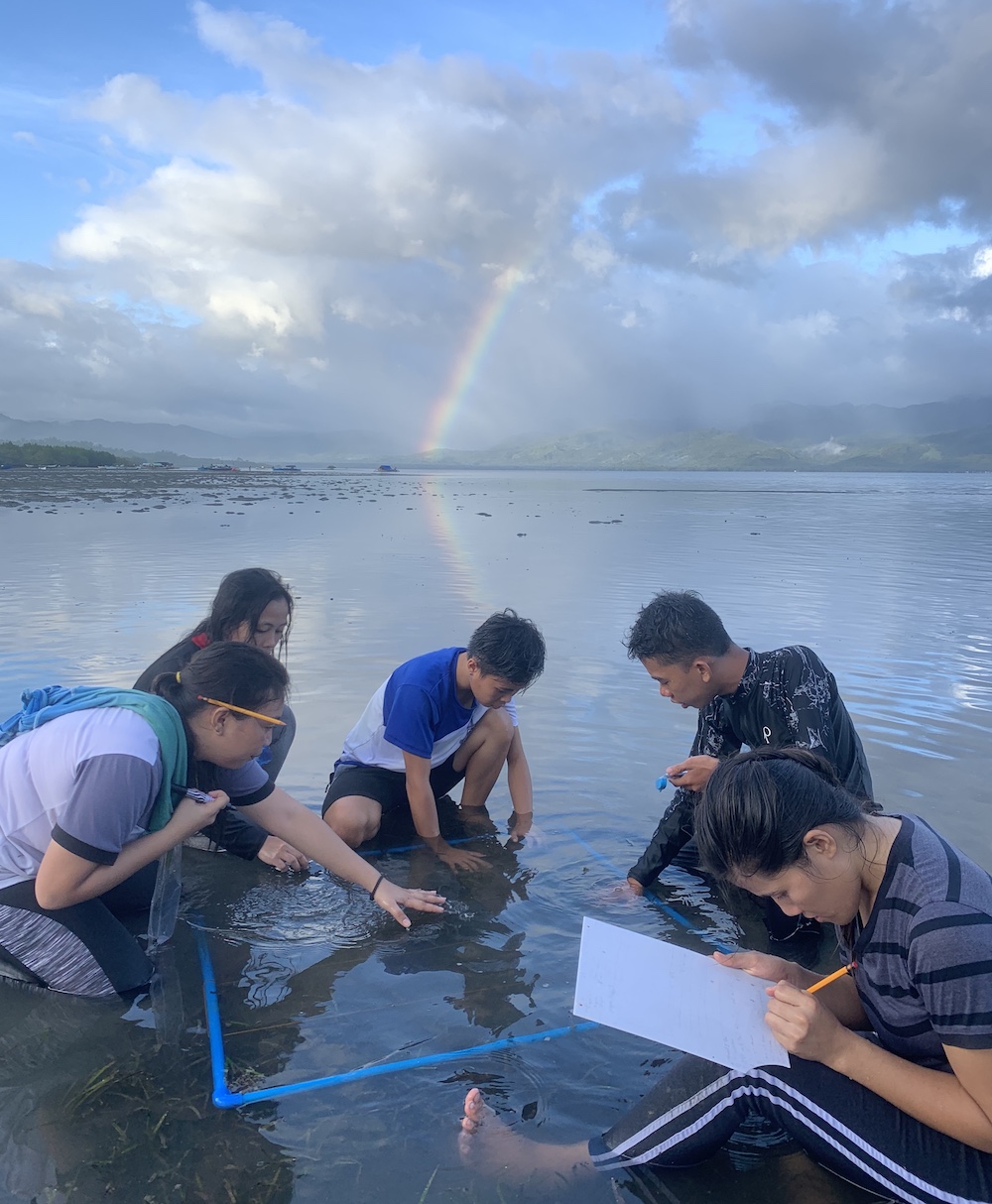

Photo: Marine biology students conduct quadrat seagrass surveys in the Philippines. Courtesy Hillard Hicks

In 2020 the world was thrust into a pandemic, which caused more than 7,000 Peace Corps Volunteers to suddenly return home from their adopted communities around the world. I was one of them.

During my first Peace Corps assignment, I served as an education Volunteer in South Africa. After service, I went to graduate school at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, studying marine biodiversity and conservation, and earned a master’s degree in June 2019. I boarded a plane to the Philippines later that year for a Peace Corps Response assignment: an aquatic resource management specialist, eager to be a champion of the marine environment in a community interested in sharing ideas about conservation. It was exciting — and it felt like the right time to venture out of my comfort zone; I was sure I’d stick out as the sole African American ecologist.

My assigned site was Leyte, on a bay frequently visited by whale sharks. I was tasked with teaching at a small technical university with a few hundred students. This remote campus focuses academic curriculum on marine biology, life sciences, and agriculture. It also provides the community with organic vegetables, compost, seaweed — and, previously, fish, at a discounted rate. The campus boasts nine fish ponds, which range in size from a football field to a basketball court. The ponds are sprinkled with nipa palms, one type of mangrove, and some other species of red mangroves. Egrets line the banks, hungrily looking for mussels or small fish to eat.

The ponds were certainly beautiful, but had deteriorated after years of neglect. At a marine science school, it’s critical that students get their hands dirty and learn about aquaculture, an important part of the economy in the Philippines. We decided it was necessary to rehabilitate the ponds to improve hands-on learning for the students and to increase the number of fish available for the community to buy.

Marine biology students in Southern Leyte, Philippines, are helping remove debris from milkfish ponds. This was part of a rehabilitation project to restore the ponds for aquaculture. Photo by Hilliard Hicks

The first problem we ran into was a need to install a submersible pump that would allow ponds to fill when the tide was too low. We received a Peace Corps Partnership Program grant from a generous donor and were able to purchase the parts and equipment we needed. In the Peace Corps, nothing gets done without the help of counterparts we work with. I don’t think my counterpart anticipated labor-intensive work when this project was proposed, but we ended up carrying about 400 feet of PVC pipe to the ponds, which were about 100 yards from the delivery site. Digging out trenches to lay pipes in 80 percent humidity and stifling temperatures was exhausting, but we got it done.

One of the biggest challenges was that high tide would cause the adjacent canal to fill partially, causing garbage to clog the channel. After building screened gates at each entrance, we were able to prevent new debris from entering the ponds. Then we had to clean the remaining garbage from the area. We enlisted the marine biology students to help, beginning work before dawn to avoid the midday heat. Every step we took, our feet sunk about a foot in the mud, so we laid boards and stiff palm leaves to make impromptu bridges and serve as handholds.

Marine biology students conduct quadrat seagrass surveys in Southern Leyte, Philippines. Photo by Hilliard Hicks

Once we cleared the ponds, built the gates, and laid the pipe, it was time to test the system. It was attached to a pump that had been sitting for five years. My counterpart was adamant that our pump worked. But one of the battery capacitors was defective. The entire pump had to be taken apart and rebuilt. Retrofitting a submersible pump and building a cage around it was no easy feat, but we had to prevent trash from being sucked in.

After months of hard work, everything was in order and we finally filled the ponds. About a week later, I was evacuated.

After months of hard work, everything was in order and we finally filled the ponds. We stocked the ponds with milkfish, locally called bangus. This bony fish lives in brackish water and is a popular fish eaten in the Philippines. Bangus is usually farmed in ponds, but can be grown in open water. In our ponds, it did extremely well. About a week after we stocked the ponds, I was evacuated.

Back in the United States, I began seeing posts on Facebook about the university selling fish from our hard-won fish pond. Knowing the pond we rehabilitated during my service was increasing their bangus productivity for the community — especially during the pandemic — was a gift. My counterpart and I, along with the hardworking marine biology students, helped the people in the community.

Even though the pandemic cut my service short, Peace Corps Response allowed me to make a long-term impact during a short-term assignment. I’m grateful for that. And, when the world returns to normal, I’ll do it again.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

Hilliard Hicks works with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fisheries, increasing awareness of coral reef ecosystems. His story originally appeared at peacecorps.gov.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe globe in 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers see more

In 1961, nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers.

THE GLOBE IN 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers — and the year after 17 nations in Africa gained independence. For the first Peace Corps programs, demand is strongest for teachers and agricultural workers. Volunteers are urged to embark on their journey in the spirit of learning rather than teaching. To lay the groundwork, Sargent Shriver, the first Director of the Peace Corps, undertakes a round-the-world trip to eight nations from April to May.

Photos by Brett Simison. Words by Jake Arce and Steven Boyd Saum

St. Lucia, an island in the Eastern Caribbean, is the third program to host Volunteers: 16 train at Iowa State University and arrive in September. The island will gain independence from the British Commonwealth in 1979.

Volunteers arrive in Colombia on September 8: All are men, ages 19 to 31. The endeavor involves a partnership with CARE. Some work in community development with the Federation of Coffee Growers, some in the Cauca River Valley in the southwest.

In Chile, 42 Volunteers train to provide assistance in community development and education as part of the Chilean Institute of Rural Education, a nonsectarian private organization. They're in service by October, working with Chilean educators in developing programs in hygiene, recreation, and farming.

Shriver tours Latin America in October. Four countries sign agreements to host Volunteers in 1962. In Brazil Volunteers will work in rural education, sanitation, and health, and in poor urban areas in the northeast. In Peru they will work in indigenous highlands and impoverished urban areas. In Venezuela, work will include teaching at a university and as county agricultural agents. Bolivia asks for engineers, nurses, dental hygienists, and food educators.

Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah speaks at the U.N. and meets JFK in March. Shriver visits him in April — not long after the Ghanaian Times denounces the nascent Peace Corps as an “agency of neo-colonialism.” But after hearing Shriver, Nkrumah says, “The Peace Corps sounds good. We are ready to try it and will invite a small number of volunteers ... Can you get them here by August?” They arrive August 30, the first Volunteers in service.

President of the Philippines Carlos B. Garcia has pursued a Filipino First policy, noting, “Politically we became independent since 1946, but economically we are still semi-colonial.” The final stop on Shriver's spring round-the-world tour, the country welcomes 128 Volunteers in October to supplement teaching in rural areas, focusing on English and science.

Nigeria gained independence from Britain on October 1, 1960. Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa asks Shriver to send teachers; the country has only 14,000 classroom slots for more than 2 million school-age children. First Volunteers arrive by end of September.

India, a country of half a billion people, is led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru — de facto leader of the nonaligned nations, those allied with neither the United States nor USSR. When Shriver visits in spring 1961, Nehru is skeptical but allows, “In matters of the spirit, I am sure young Americans would learn a good deal in this country and it could be an important experience for them.” He agrees to host a small number of Volunteers in Punjab. A cohort of 26 arrives December 20. After India agrees to host Volunteers, so do Pakistan, Thailand, and Malaya.

Pakistan’s President Mohammad Ayub Khan came to power in a coup in 1958 and was elected by a referendum in 1960. Addressing the U.S. Congress in July 1961, he calls for more financial assistance. The first group of Volunteers arrives in West Pakistan in the fall to serve are junior instructors at colleges, as well as teachers of farming methods and staff at hospitals.

First Volunteers arrive in Tanganyika on September 30: civil engineers, geologists, and surveyors, there to build roads and create geological maps. The country is a U.N. trusteeship that achieves full independence in December. Also note: in October, 26 Volunteers begin training for service in Sierra Leone in 1962.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe skateboarding project and learning to paddle together. see more

Nobody wanted it to happen this way. Evacuation stories and the unfinished business of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world.

The Philippines | Diane Glover

Home: Valdosta, Georgia

When Diane Glover arrived in the Philippines in July 2018, it was a sort of homecoming — to the country where she was born and left at age 11. She was raised by her older sister in Washington state and Georgia. “So many people invested in my success,” she says. Returning that investment seemed natural; empowering girls is something she cares about deeply — especially survivors of sexual violence.

She was a youth development Volunteer in Tacloban City on the island of Leyte. She worked with dozens of street children. One effort was the “skateboarding project,” which rented out skateboards — but not for money. The goal was to get kids into the community office and help them learn. Every minute they participated in reading, writing, or gardening bought a minute of skateboarding. The work taught Glover patience: “I can’t necessarily say, ‘I transformed six lives today.’ Most of the time our success — we don’t see that until down the road.”

“I can’t necessarily say, ‘I transformed six lives today.’ Most of the time our success — we don’t see that until down the road.”

Investing in their success: Diane Glover, left, with kids in Tacloban City. Photo by Diane Glover

With six months left, she was worried about cutting it close with the terms of a grant. There was another project proposal — and wouldn’t it be good to extend for a third year? Then came the email.The islands of the Philippines are scattered over hundreds of miles; evacuation was decentralized. Peace Corps staff flew from Manila to Cebu City to ensure that Volunteers consolidating there got home safely. “They just wanted to support their Volunteers till the very end.”

Crisis brought home a new lesson: Stop worrying about grants and project deadlines. “The evacuation has given us a snap of realization: Your relationship is your success—the relationship that you create in your community.” Yet suddenly that was gone.

The Philippines | Rok Locksley

Home: Chicago, Illinois

Volunteer Rok Locksley, left, supported Nibarie Nicolas in his projects focused on marine resources. Photo courtesy Rok LocksleyI met Nibarie Nicolas just before our swearing-in ceremony in Manila. I knew him as Ban2x (Ban-Ban). He’s mid-twenties, full of energy, curiosity, and infectious joy. He had recently been hired as fisheries technician for the Municipal Office of San Jose in the Visayas region. He was responsible for local marine resources, programs, and events. He was passionate about working with local fisherfolk. And he was assigned to be my counterpart.

I served as a Volunteer in Moldova (2005–08) and worked as a recruiter for Peace Corps before my wife, Genevieve, and I went back as Volunteers in Philippines. I supported Ban2x in his projects: developing a guardhouse for our marine sanctuary, programs for fisherfolk, agro-tourism events, and education about marine resources.

Within minutes of us meeting, Ban2x asked if I liked dragonboating. I had a vague familiarity; I’m an avid whitewater kayaker. He had assembled a dragonboat team from the fisherfolk communities; he was drummer and captain. They had never paddled before as a team, but they spent days and nights on the water in canoes they call sakayans, fishing the Tañon Strait. They borrowed a boat for their first race and blew the competition out of the water.

Dragonboating became a major part of my life. After a day in the office working on marine policies or presentations, Ban2x and I headed to practice. We paddled until sunset, then sat on the beach and watched stars reclaim the sky. We shared thoughts and dreams and life lessons. We ended each night with traditional goodbyes in Binisayan: “Kitakits”—which isn’t so much “goodbye” as “Until we see each other again.”

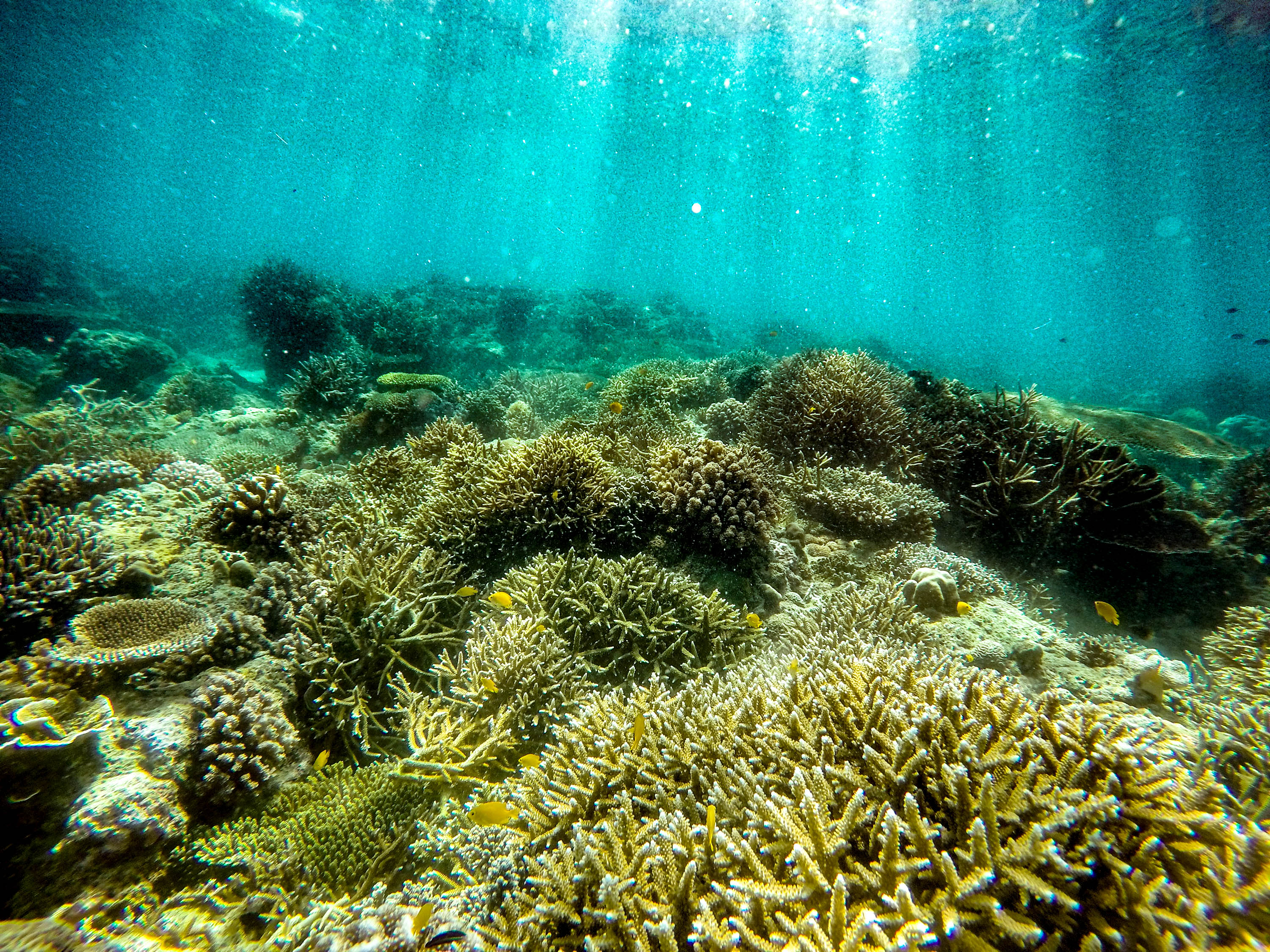

Genevieve became fast friends with Ban2x’s grandmother. We attended birthday parties and fiestas with his family. He took time to walk me through basic introductions, made sure I knew how to dress for various occasions, who to thank. While he was tasked with protection of the park, he had never donned SCUBA gear to see it underwater. So I arranged for him to get his diving certifications. Our first dive we saw lobsters, turtles, sharks, and stunning coral formations. When we surfaced, I saw the wonder in his eyes.

We created plans for coastal resource management and a marine protected area. We had big ideas for 2020. As January ended and news of the virus spread, we intensified our work. February rolled in fast. March, I could see the writing on the wall. I tried to wrap up projects and spoke with Ban2x at length about what needed to happen professionally if Genevieve and I left.

“When we surfaced, I saw the wonder in his eyes.” Photo by Rok Locksley

The first week in March we went on lockdown. I talked with Ban2x about evacuation. He wasn’t worried. Peace Corps evacuated us in 2019 to Manila when a typhoon came close. We returned a week later. When we got the call for consolidation in mid-March, I knew it would be the end of my service. I asked Ban2x to come over.

He arrived in his usual chipper demeanor. We talked on the porch, then I brought him into the house and started pointing out things he could take, what to give to the fisherfolk. After I showed him our bicycles, it registered on his face that we were truly leaving.

I firmly believe that one-to-one relationships built at a grassroots level between people who are fundamentally different is the best pathway to world peace. But I forgot how much it hurts to leave your friends.

When people talk about Peace Corps, they are quick to mention Volunteers and service. Maybe they get around to speaking about the three goals or cultural exchange. Most people forget about the actual mission of the agency: world peace and friendship. I firmly believe that one-to-one relationships built at a grassroots level between people who are fundamentally different is the best pathway to world peace. But I forgot how much it hurts to leave your friends.

Ban2x showed up at our house early the next day. He brought his family car to shuttle us to the seaport. We were on the last boat out. We loaded our bags. He pledged to look after our dog. We hung around the port until the last possible minute. Then I grabbed my dragonboat paddle and turned for one last look at my best friend. “It’s not goodbye,” I said, “just until we see each other again.”

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Another idea: Support the work we’re doing to help evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleWe’ve got some learning and some work to do. see more

We’ve got some learning and some work to do.

That’s true for the Peace Corps community. For this nation. For this planet.We’re facing hard questions and grappling with systemic injustices that have been centuries in the making. We envision a vibrant and united community, here at home and around the world.

What we do know: Working together as partners is essential. Rok Locksley is the Volunteer who took this photo in the Philippines. He supported Nibarie Nicolas in work developing sustainable projects for communities and protecting marine areas. They quickly learned to paddle together, learned new ways of seeing.

Our work is just starting.

Support Volunteers back in the States and their ongoing work around the globe.