Activity

-

Tiffany James posted an articleUpdates from the Peace Corps community — across the country and around the world see more

News and updates from the Peace Corps community — across the country, around the world, and spanning generations of returned Volunteers and staff.

By Peter V. Deekle (Iran 1968–70)

Gloria Blackwell (pictured), who served as a Volunteer in Cameroon 1986–88, was recently named CEO of the American Association of University Women — a nonprofit organization advancing equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. In April, Colombia bestowed citizenship upon Maureen Orth (Colombia 1964–66) in recognition of her lifetime of work supporting education in the country. Writer Michael Meyer (China 1995–97) recently published Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet, which explores Franklin’s deathbed wager of 2,000 pounds to Boston and Philadelphia with the expectation that the investments be lent out over the following two centuries to tradesmen to jump-start their careers. Plus we share news about fellowships, a new documentary, and poetry in translation from Ukrainian.

Have news to share with the Peace Corps community? Let us know.BELIZE

Eric Scherer (1975–76) was appointed as state executive director for the USDA Rhode Island Farm Service Agency (FSA) by the Biden Administration in late April. He previously worked as a USDA technical service provider and USDA certified conservation planner, providing technical consulting work for the public and private sector on natural resource issues. Prior to his work as a technical consultant, he served as the executive director of the Southern Rhode Island Conservation District, where he provided program leadership for the conservation district programs that focused on conserving and protecting natural resources. Scherer brings to his new role 37 years of federal service experience, including work for the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service in six states in various positions. As state executive director, he will oversee the delivery of FSA programs to agricultural producers in Rhode Island.

CAMEROON

Gloria Blackwell (1986–88) was named chief executive officer of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) last October. She is also AAUW’s main representative to the United Nations. For nearly two decades, Blackwell managed AAUW’s highly esteemed fellowships and grants program — awarding more than $70 million in funding to women scholars and programs in the U.S. and abroad. Before she joined AAUW in 2004, Blackwell’s extensive experience in fellowship and grant management expanded during her time with Institute of International Education as the director of Africa education programs. While in that position, she oversaw girl’s education programs in Africa and mid-career fellowships for global professionals. In addition to serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Cameroon, she served as a Peace Corps staff member in Washington, D.C.

CHINA

The latest book from Michael Meyer (1995–97) is Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet (Mariner Books), which explores Franklin’s deathbed wager of 2,000 pounds to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia with the expectation that the investments be lent out over the following two centuries to tradesmen to jump-start their careers. In an interview on NPR’s Morning Edition, Meyer shared his own surprise at discovering the story behind this wager. “I didn't know that his will was essentially another chapter of his life,” he said, “that he used his will to settle scores with family, with enemies, and he used his will to pass on his legacy and his values and to place a large bet on the survival of the working class in the United States.” Meyer was among the first Peace Corps Volunteers who served in China. Since serving there, he has written three reported books set in China, starting with The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed. His writing has earned him a Whiting Writers’ Award for nonfiction, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Lowell Thomas Award for Best Travel Book from the Society of American Travel Writers. Meyer’s stories have appeared in various publications, including The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Time, the Los Angeles Times, and the Paris Review. He was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to Taiwan in 2021.

COLOMBIA

On April 27, Maureen Orth (1964–66) was honored in a ceremony in which she was sworn in as a citizen of Colombia — in recognition of her lifetime of service to the people of Colombia. That all began with serving in the Peace Corps. By video conference, President of Colombia Iván Duque Márquez administered the oath of citizenship to Orth during an elegant ceremony hosted by Colombian Ambassador to the U.S. Juan Carlos Pinzón at his residence. In 2005, at the request of the Secretary of Education of Medellin who asked her to empower the children in her school to become competitive in the 21st century, Orth founded the Marina Orth Foundation. It has since grown to include 21 public and charter schools offering computers for every child K-5, STEM, English, and leadership training, including robotics and coding. In 2015, then-Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos awarded her the Cruz de San Carlos, Colombia’s highest civilian award for service to the country. She also was awarded the McCall-Pierpaoli Humanitarian of the Year Award from Refugees International.

Elyse Magen (2018–20) assumed a new position in April as program associate for the Udall Foundation — an independent executive branch agency providing programs to promote leadership, education, collaboration, and conflict resolution in the areas of environment, public lands, and natural resources. Magen brings to her new role diverse experience addressing economic, social, and environmental issues by working with diverse communities in the United States and Latin America. While earning her bachelor’s in economics and environmental studies at Tulane University, Magen worked as a peer health educator at the university’s wellness center, and she served as an environmental economics intern at the U.S. Embassy in Ecuador during the summer of 2017. In 2020, Magen was evacuated from her Peace Corps service as a community economic development analyst in Colombia due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Refusing to let that be the end of her Volunteer story, she obtained an NPCA Community Fund grant to complete one of her unfinished secondary projects with “Chicas de Transformación,” a womens’ chocolate cooperative in Santa Marta, Colombia. With the support of a NPCA community fund grant, Magen helped the collective build a new workspace and purchase machinery that would allow the cooperative to start selling a new line of chocolate products they were unable to produce before, increasing their profit margins.

GUINEA

Jessica Pickering (2019–20) is a 2022 Templeton Fellow within the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Africa Program. In May 2022, she graduated from Tulane University with a master’s degree in homeland security and a certificate in intelligence. From the University of Washington in Seattle, she received her bachelor’s in international affairs, focusing on foreign policy, diplomacy, peace, and security. Her research interests include international security, foreign policy, and the effects of gender equity, climate change, and governance on policy and stability in West Africa.

MOROCCO

Mathew Crichton (2016–17) is now a senior consultant at Deloitte, advising government and public sector clients through critical and complex issues. From 2018–22, Crichton served as an IT and Training Specialist with the Peace Corps Agency and president of its employee union.

MOZAMBIQUE

Charles Vorkas (2002–04) is a faculty member at Stony Brook University’s Renaissance School of Medicine. With a diverse background in research and international patient care, Vorkas is leading efforts in his newly-established lab to better understand disease resistance. It was while serving as a Volunteer in Mozambique that he witnessed the effects of infectious diseases and was often in contact with individuals who were suffering from diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis. “It definitely confirmed that this was a major global health problem that I would like to help to address in my career,” Vorkas said.

ROMANIA

Matt Sarnecki (2004–06), a journalist, producer and film director at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, had a world premiere in May at Hot Docs 2022 in the International Spectrum Section of his documentary film, “The Killing of a Journalist.” It tells the story of a young investigative journalist, Ján Kuciak, and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, who were brutally murdered in their home in Slovakia in February 2018. Their deaths inspired the biggest protests in Slovakia since the fall of communism. The story took an unexpected turn when a source leaked the secret murder case file to the murdered journalist’s colleagues. It included the computers and encrypted communications of the assassination’s alleged mastermind, a businessman closely connected to the country’s ruling party. Trawling these encrypted messages, journalists discovered that their country had been captured by corrupt oligarchs, judges, and law enforcement officials.

UKRAINE

Ali Kinsella (2008–11), together with Dzvinia Orlowsky, is the translator of the poetry collection Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow (Lost Horse Press, 2021) by Ukrainian writer Natalka Bilotserkivets. Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow brings together selected works written over the last four decades. Having established an English language following largely on the merits of a single poem, Bilotserkivets’s larger body of work continues to be relatively unknown. Natalka Bilotserkivets was an active participant in Ukraine’s Renaissance of the late-Soviet and early independence period. Ali Kinsella has been translating from Ukrainian for eight years. Her published works include essays, poetry, monographs, and subtitles to various films. She holds an M.A. from Columbia University, where she wrote a thesis on the intersection of feminism and nationalism in small states. She lived in Ukraine for nearly five years. She is currently in Chicago, where she also sometimes works as a baker. The collection is shortlisted for the 2022 Griffin Poetry Prize.

PEACE CORPS STAFF

Kechi Achebe, who directs Office of Global Health and HIV for the Peace Corps, was recently among those honored as part of a special event recognizing leaders in the Nigerian Diaspora in the United States. Themed “The Pride of Our Ancestry; The Strength of Our Diaspora,” the event was hosted by the Nigerian Physicians Advocacy Group and Constituency for Africa and included special guest Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, director-general at the World Trade Organization. “There is no greater blessing than to be honored by your own community,” Achebe said. “I stand on the shoulders of women and other global health leaders who started the fight for global health equity for all, especially for disadvantaged communities all over the world.” Achebe has served in her role with the Peace Corps since December 2020. She previously led leadership posts with Africare and Save the Children.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleEvacuation, some Peace Corps history, and #apush4peace see more

Evacuation, some Peace Corps history, and #apush4peace

When Coronavirus Unmapped the Peace Corps' Journey

Jeffrey Aubuchon (92252 Press)Reviewed by Jake Arce and Steven Boyd Saum

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the unprecedented global evacuation of Peace Corps Volunteers. Jeffrey Aubuchon brings together stories of some evacuees chronicled in WorldView: Chelsea Bajek, who was working with a women’s group in Vanuatu; Jim Damico, evacuated from teaching in Nepal; Benjamin Rietmann, yanked from his work with farmers and young entrepreneurs in Dominican Republic; and Stacie Scott, who left behind the community she was serving as a health volunteer in Mozambique.

Aubuchon follows in greater depth two Southern California high school sweethearts, Jacqueline Moore-DesLauriers and Dylan Thompson, who served together in Morocco. In Sefrou (pop. 80,000), on the outskirts of Fez, they taught English classes and hosted a STEMpowerment workshop for girls at the local dar chabab (youth center). They established a girls’ volleyball team that played its first game on March 5. Ten days later, Peace Corps announced its global evacuation.

“Never in the last 40 years has the Association’s mission been more vital.”

The book also serves up some context for 2020 — when each week seemed like a year unto itself. And National Peace Corps Association gets more than a passing nod — particularly its crucial work advocating for evacuated Volunteers, which helped secure additional benefits for them and $88 million in supplemental funding for Peace Corps. “Never in the last 40 years has the Association’s mission been more vital,” Aubuchon writes. “Indeed, on March 16, 2020, NPCA President Glenn Blumhorst released a statement not only voicing support for all of the EPCVs, but also outlining a national plan to coordinate support for these evacuees among the Peace Corps, the NPCA, and the RPCV community itself.”

Aubuchon served as a Volunteer in Morocco 2007–09. “I walked my own Peace Corps journey in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the Casablanca bombings of 2003,” he writes. He applied for and received grant funding to help build four libraries. In fall 2019, he was teaching a course in Advanced Placement U.S. History at a high school in central Massachusetts. A lesson in Cold War history led students to do more than merely talk about global problems; they founded a youth venture — and began raising funds to support Peace Corps Volunteers’ projects. Taking the acronym for the class, APUSH, they hasthtagged their effort #apush4peace. They convinced community members to put up $1,000 in seed funding — and then, through fundraising, more than tripled that, “allowing them to help a PCV in Zambia build a hospital clinic ward and help another build a library in Mozambique.”

Paama Custom Arts Festival: Traditional basket weaving on Vanuatu. Chelsea Bajek worked with these women to launch a business project. Photo by Chelsea Bajek

One of those APUSH students, Olivia Wells, takes over the closing chapter of the book. She observes: “Few people know that there are ways to help educate adolescents in Eswatini (Swaziland) about HIV/AIDS, or to help local farmers in Malawi construct an irrigation system to decrease water erosion on their farmland.”

This is a project that’s meant to give back; one dollar from each copy sold goes to Kiva.org to support microfinance projects, and another dollar goes to support National Peace Corps Association.

As for the stories of the Volunteers who were evacuated: Those journeys continue beyond the pages of the book. For example, Jim Damico, a three-time Volunteer, didn’t wait for Peace Corps to return to Nepal. He went back on his own in January 2021 and has been mentoring teachers. Chelsea Bajek, who was serving in Vanuatu, had successfully applied for a Peace Corps Partnership Program grant to purchase equipment and materials for skill-building workshops at the Paama Women’s Handicraft Center. But those funds were cut off when Bajek was evacuated. Thanks to crowdsourcing and NPCA’s Community Fund, in 2021 that project was fully funded and will, Bajek reports, increase opportunities for women’s economic development and empowerment.

-

Communications Intern posted an articlePC counterparts: one person in the community tasked with helping make this endeavor possible see more

Every Volunteer has a counterpart. That’s Peace Corps lingo for one person in the community tasked with helping make this endeavor possible.

Interviews Edited by Steven Boyd Saum and Cynthia Arata

Photo: Sharmae Stringfield (left) Chippie Ngwali. Courtesy Sharmae Stringfield.

Malawi | Sharmae Stringfield, Volunteer

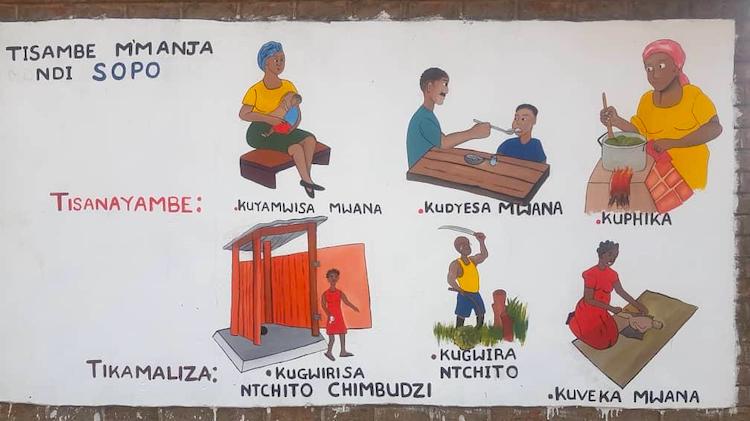

Home: Virginia, United StatesThe day I had to leave my village in the district of Blantyre was the day the painter I hired finished our mural at the health center: a dedication to sanitation and critical times to wash hands. Seeing as the evacuation was due to a virus that spreads rapidly through a lack of both those things, it was a fitting project to have left behind.

I left my neighbor and best friend, Vincent Zitha. I had less than 24 hours to say goodbyes. My co-workers were health care workers, teachers, community leaders. One of my favorite responsibilities was supervising the local youth club that I helped re-establish. We were able to have two community service projects, and we invited health workers to give talks. The youth absorbed these health messages and turned them into song and plays. After I left, they created a play about coronavirus and performed it at the health center.

We were going to tackle tough issues troubling girls in the community — including dropping out of school due to early pregnancies and young marriages.

I co-facilitated an after-school girls’ club with the chair of their mothers’ group, using the Go Girls curriculum. The day I got the email to evacuate would have been my last day to facilitate. Schools then closed to take precautions against COVID-19. The work I was doing came to a halt; the program was only half complete. The head teacher and I have remained in contact to ensure its completion. Shortly before evacuation, I began a partnership with a local NGO, FACT Malawi. We were going to tackle tough issues troubling girls in the community — including dropping out of school due to early pregnancies and young marriages. Youth of Malawi need programs that cater to teaching young boys how to be gentlemen and teaching young girls how to assert and protect themselves. Communities can benefit from the Peace Corps approach to both community health and environment issues. Our fellow Malawians valued our presence in their country, and they welcomed us with both hands.

Sharmae Stringfield and Mdeka Youth Club. Photo courtesy Sharmae Stringfield.

Malawi | Chipiliro Ngwali, Counterpart

Home: Phalula village in Balaka districtI am married and I have a son, and I am now working under the Ministry of Health as a health surveillance assistant at Mdeka Health Center. We do field work in hard to reach areas: monitoring health of community members, engaging in health talks, and providing immunizations and other preventative medication. Malawi has few health workers in rural centers, so people have limited access. We work in collaboration with Peace Corps; they help fill the gap — and bring volunteers like Sharmae. This made me excited.

In the last few months, there have been so many changes due to coronavirus. Health workers’ efforts have diminished; they are afraid of contracting the virus, since there’s little personal protective equipment. Society discriminates against health workers because of that risk. Many health centers close early to avoid overcrowding. Projects initiated by Sharmae have been affected. Groups she brought together have stopped receiving education she used to provide. Safety measures have prevented the other programs from continuing.

Americans need to understand that the work we did was important … The work that was started doesn’t have to end.

People are still eager to know more and acquire skills Sharmae was teaching. As for the mural Sharmae was working on at the health center: With people being afraid of getting coronavirus, we have been avoiding large gatherings. Instead, we let people view the mural to self-educate. People see the times when it’s critical to wash hands. They see how waterborne illnesses happen. Americans need to understand that the work we did was important. There are skills that were taught and prevention techniques that can be practiced.

The work that was started doesn’t have to end. Peace Corps Volunteers should continue to pass along information on COVID-19 to counterparts who can reach remote areas. They can teach ways of ensuring food security in this time of pandemic. And PCVs can stay in communication with counterparts to try to preserve any work that can continue after the coronavirus is less of a threat.

Malawi: Health mural, Mdeka Health Center. Photo by Sharmae Stringfield.

Panama | Bill Lariviere, Volunteer and José María Barrios, Counterpart

Panama: Volunteer Bill Lariviere (left) and counterpart José María Barrios, admiring the work they organized for a reforestation event in Nuario, Los Santos. Photo by Eli Wittum.

Morocco | Omar Lhamyani, Counterpart

Home: Zagora ProvinceI was born and raised in a village called Tazarine in southeast Morocco. It was once a green oasis with an economy centered on agriculture; years of drought and desertification have changed the region into more of a commercial area.

I was introduced to Peace Corps in 2010. I have worked with three cohorts of Volunteers as a language and cross-cultural facilitator, counterpart, and language tutor, and as member of the multimedia committee creating and translating content that showcases the amazing work Volunteers and community youth are doing.

This work is life-changing for the youth in my community, just as it was for me.

We focus on youth in development. This work is life-changing for the youth in my community, just as it was for me. As a young high school student I participated in a linguistics camp in my town where I felt the influence of PCVs. They were role models for me.

Most recently I worked with Gio Giraldo. She worked with community members and focused on girls’ empowerment with the Dar Chabab Youth Club. She is an accomplished soccer player and trained withcollegiate and professional athletes in the U.S. That was new and fascinating, especially for the girls in Tazarine. It is rare to see boys and girls playing sports together in rural villages. Gio wanted to create a space for girls to feel welcome to play soccer. Now I see boys and girls playing competitive soccer games together.

We are lucky in Tazarine to have had PCVs for more than 10 years. They help students improve their English skills and connect us to resources, such as scholarships. Ideas and perspectives that Volunteers have brought have influenced and inspired us.

When I first heard of the evacuation, I couldn’t believe it. But I knew the situation could become more difficult. The community understands why Gio had to leave; her family must want her near in this time. We hope the sadness we feel seeing Gio go will be temporary — but her impact on our community will continue to thrive.

Community members ask about Gio all the time—and if she will come back. Mostly the girls from the community ask me if they will continue their soccer project with Gio. Her kindness, and the way she carried out her service, made the community trust and respect her.

Omar Lhamyani. Photo by Giovana Giraldo.

Morocco | Giovana Giraldo, Volunteer

Home: Miami metropolitan area, United StatesThey called the region the gateway—the entrance to big cities from Sahara country. Doors open up to the desert. There are beautiful canyons and a blend of cultures. I arrived last year. We were excited about a grant proposal from the U.S. Embassy to organize a summer leadership program for youth. I was coaching a girls soccer team that started off as pick-up soccer; the dream was to develop it into an organized association. Soccer can be great for integration. I’ve played all my life. Opportunities I’ve had are due to people coming together to make things happen. That was my goal in Morocco. There was amazing talent. Traveling has shown me that talent is equally distributed but not necessarily opportunity.

Omar is a selfless and motivated person. He is incredible. Peace Corps influenced him when he was younger; he has repaid that tenfold.

Omar is a selfless and motivated person. He is incredible. Peace Corps influenced him when he was younger; he has repaid that tenfold. Anyone who reached out — he would connect and help.

Other counterparts I worked with were also focused on providing opportunities. I like to think the work will go on without me being there. Though evacuation has thrown all my emotions into a washing machine. I’m disappointed because of the timing. Sad because of what it all meant to me. For Moroccan staff, Peace Corps means livelihoods, careers. They were nothing but supportive and positive. I feel like I’ve lost a little family.

Girls hiking expedition. Photo by Giovana Giraldo.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleFive country directors tell the stories of Peace Corps evacuation. see more

When times are good, being a country director for Peace Corps may be the best job in foreign affairs. This has not been such a time.

As told to Steven Boyd Saum

Photo: Vyshyvanka Day, when schoolchildren don the traditional Ukrainian shirt — and here, pose as one. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Kim Mansaray | Country Director, Mongolia

JANUARY AND NEWS OF THE VIRUS came out in China. Mongolia says we’re not sending kids back to school. Our winter break became endless winter break. Then the virus exploded in China, and Mongolia went on hardcore lockdown — borders and flights.

From time to time in Mongolia, there’s an outbreak of something, then a quarantine — fairly routine. That was on our minds: Watch how this plays out. The clincher was when flights from Seoul were canceled. I talked to the embassy and said, If people need to be medically evacuated, we’re not gonna be able to get them out.

The farthest part of the country is normally a 40-hour bus ride. It took five days with help from embassy cars to caravan all Volunteers back in. And of course, because it’s Mongolia, there was a blizzard.

Volunteers just a few months in were put on administrative hold. Then, in mid-March, Washington moved everybody to Close of Service. My Volunteers were giving me grief. I said, I get your frustration and your anger. But this is unchartered territory for Peace Corps.

Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the volunteers back as soon as possible.”

Mongolia on horseback. Photo by Antonio Mercatante

Fast forward to June: Our staff in Mongolia have been out and about and in the countryside, visiting potential sites, picking up luggage that Volunteers left behind. And making honest assessments: Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the Volunteers back as soon as possible.” There’s a real connection. Volunteers are staying in touch with communities. Mongolia is incredibly wired; they use Facebook for everything.

Here, they see what’s happening in the U.S. Three, four days a week, people come in my office and ask: “What is going on?” Diplomatically I say, “Our democracy is right out there for you to see. It’s messy and it’s ugly, and it’s been tough.” But they know what the Volunteers have been doing in communities. That resonates here. Mongolia has an incredible commitment to not allowing community spread of COVID-19. They understand why the Volunteers left. And they’re uniformly asking, “When are they coming back?”

Ukraine: The winter walk to school. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Michael Ketover | Country Director, Ukraine

FRIDAY THE 13TH of March, still only three cases confirmed in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government acts quickly: bans foreigners from entering, effective in 48 hours; 170 border checkpoints closed. We go to alert stage. Overnight a nationwide lockdown is imposed. We activate standfast. Saturday morning, airports close. Time to evacuate.

I was in Kryvyi Rih at a training with Volunteers and Ukrainian partners; took the 7-hour train back to Kyiv Saturday morning. Peace Corps in DC agrees on evacuation, finds a charter plane from Jordan, to arrive Monday. PC Ukraine, largest post globally, had 274 Volunteers serving; a large group completed service earlier that winter. Imagine doing this with the full 350 PCVs, I thought. We tell all Volunteers to get to Kyiv by Sunday night; they do. We get them to the airport — which is closed, skeleton staff. Still only seven cases in Ukraine. We wait. Flight delayed several times, then, about midnight, canceled. Hotels were closing. We found rooms in three; staff bought PCVs water and food, since restaurants were closing.

Tuesday’s charter: delayed then canceled. The company hadn’t arranged landing fee payment, secured a ground crew, etc. Wednesday: flight delayed several times, then canceled last minute. Despite support from the U.S. Embassy in Amman, the government of Jordan wouldn’t let the plane leave because of new COVID restrictions. Wednesday night I propose asking the U.S. military if we can fly Volunteers out on a military aircraft. And I talk to the CEO of a small startup airline in Ukraine interested in making its first flights to the States.

Thursday, 19 cases. We’re getting inquiries from congressional offices about concerned Volunteers’ parents: What’s going on? Thursday: delays, cancellation. Peace Corps HQ locates a different charter company from Spain. I insist on being put directly in touch with them. Thursday night 10:30 p.m., wheels up Madrid. We move PCVs in six different buses, with police and Regional Security Officer escort since it is now illegal to gather more than 10 people. At Kyiv airport, there’s a technical issue: They can’t issue or print boarding passes. So airport staff write them out by hand. Check-in took 10 hours. Friday morning, 6:20 a.m., plane departs. Kyiv to Madrid to Dulles to homes of record.

The real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter.

When I say we it’s the incredible PC local staff. Many had been through evacuation before, in 2014. I managed an evacuation in Papua New Guinea years ago but much less hectic and with only 22 PCVs. This time I was managing it from my Kyiv apartment — Friday I received notice that I had to self-quarantine because I had returned from Europe within the past two weeks. So I’m calling every Volunteer I could to say goodbye during that overnight check-in. During all this we’re posting on social media every day. This was time for gratitude: to counterparts and local staff, host families and government ministry partners, superstar volunteer wardens and our dear Volunteers. I encouraged the Volunteers to stay in touch with counterparts, work remotely if they could — on grant proposals, civic education with youth, English clubs on Zoom, anything; 100 evacuated PCVs have put in nearly 2,000 hours of virtual volunteering already.

Staff here have restarted programs before. They are working hard even without PCVs in country to maintain meaningful contact with counterparts. They know how to do it.

As for unfinished business, there’s goal one for Peace Corps — work Volunteers do in teaching, youth and organizational development. That’s important, but the real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter. When I talk to counterparts, local staff , and Volunteers, I emphasize this. Counterparts love it: Work, yes, but also inviting Volunteers to birthday celebrations, funerals, and weddings, berry picking in the forest — that makes this experience unique and awesome. The Third Goal, that’s unfinished: making America less insular — helping Americans appreciate the realities of life in different places. Those three goals, equally important, are the beauty of our wonderful organization.

Ghana: Gathering for a baby-naming ceremony. Photo by Meg Holladay

Gordon Brown | Country Director, GhanaIT HAD ALREADY BEEN A TOUGH YEAR for us in Ghana. In October, one of our Volunteers, Chidinma Ezeani, died after a tragic gas accident in her home. Thirty-nine Volunteers had to be relocated out of the northern part of the country because of security concerns across the border. Peace Corps Niger is closed because of security; Burkina Faso, too.

Then the virus: by March, regular emergency meetings at the embassy. Countries started closing, restricting airspace. It looked like Ghana was going to close — within the span of probably half a day. Sunday night, they said, Go in tomorrow and tell all 80 Volunteers to move. How fast can you do it? Now, our organizational culture in Peace Corps is not like the military: Here are your orders, execute. But in a moment like this, it has to be: Do this now — like now now.

My former boss used to say, “Being Peace Corps country director is the best job in foreign affairs.” I started as country director in Benin in 2015, then in Ghana in 2018. Along with the joy of the work also sometimes comes tragedy. So how do you be the best when times are the worst? Executing an evacuation takes massive logistical effort and focus. It was us all together — the Volunteers and the agency — that were able to make that happen. We had planes that were supposed to show up that didn’t. When we did get a plane — well, it had been a tough week for me personally, too. My wife had injured a muscle in her leg. So it’s 80 Volunteers, my wife in a wheelchair, our 3-year-old, our 7-year-old, all of our luggage — you can’t make up that level of difficulty. It was level 10.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

As hard as this has been, here’s something that I think has become clear to a lot of the Volunteers: You don’t stop being a Volunteer just because you’re no longer at your site in a country. We’ve got the technology now that allows many Volunteers to be connected all the time. But that doesn’t change the fact that you need to be able to communicate with people in front of you. You need to be able to read people’s emotions and speak with them in a way that is that being empathetic to what they’re going through.

We have to wrestle with what Peace Corps means in the modern world. How does it remain relevant? Ghana is the oldest Peace Corps operation in the world. It started in another era; 1961 was the year of Africa, when some 20 nations became independent. In 1960, the Prime Minister of England, Harold Macmillan gave a speech about “the wind of change” blowing through the continent.

In Ghana, one question is: How do we keep Peace Corps from seeming like a piece of old furniture? It has always been there. Kwame Nkrumah is always a big hero. John F. Kennedy is a big hero. America and Ghana have always had a close relationship. But how do we renew excitement among the government and people of Ghana — to understand that these Volunteers who are capable and tech-savvy, involved and committed, have something to offer? It’s a welcome challenge.

For the agency this is a massive undertaking in terms of charting the way forward: what the focus areas are going to be, what the footprint is going to be — what sectors, sizes, countries? All of that is going to have to be decided on an individual basis. As I like to tell Volunteers: Any victory lies in the organization of the non-obvious.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

Morocco: Girls’ hiking expedition. Photo by Gio Giraldo

Sue Dwyer | Country Director, Morocco

WHEN WE STARTED an in-service training there were maybe two cases in Morocco — a country of 35 million. But come Friday morning, March 13, I don’t like where this is going. They shut down flights to Italy, are talking about shutting down flights to France — our primary means of getting out. We cancel the last few days of training. We send Volunteers back to their sites, put them on standfast.

Saturday morning, I call the Deputy Chief of Mission at the embassy and tell him I think I have to get Volunteers out; if we have to med-evac someone, we’re in trouble. We’ve got 183 Volunteers and Morocco is the size of California. For some Volunteers it takes two days to get back to site; they get a day to pack, say goodbye. In Rabat I figure we’ll have three days for a program to wrap things up. The embassy says you’ve got until next Saturday … then Thursday … then Wednesday. OK, here we go. The Moroccan government keeps moving the time when we can fly. I realize, as this is happening, that I still have some muscles working from my humanitarian aid days; I evacuated NGOs out of Liberia in 1999 during the civil war.

A lot of Volunteers email me saying, “Please don’t send us home, we want to be here in solidarity with the Moroccans.” But they come. Some have problems getting back to Rabat — harassment on buses, people saying foreigners brought in COVID. So our Moroccan staff charter buses and send them out to consolidation points.

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh.

At the airport we have a charter flight with maybe 225 seats for Volunteers only. They start calling: “My grandmother and my mother are here — and the airport’s closed.” So we say yes. Then: My parents, my aunt , my brother. So we have to finish what we started. Thursday at 2 a.m., the plane takes off. Second-year Volunteers knew they were being COS’d. First-year Volunteers were told they were on administrative hold. While they were flying that changed. They got off the plane, they got a different message. That was soul-crushing.

Peace Corps Morocco is one of the oldest programs, and currently the only one in the Arab world. We’re the largest youth development program; it’s our sole area of focus. The evacuation was a huge earthquake with all the aftershocks. And it’s not just for Volunteers. We’ve got host families calling and saying, “I can’t reach my volunteer daughter, son” — because their number changed. “When we see what’s happening in the United States, we’re really worried. Are they OK?”

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh. If we were to do training in a completely different way, what would that look like? So this is an important time for innovation and rethinking our models

.

Paraguay: Scenes from an Instagram feed before evacuation

Howard Lyon | Country Director, Paraguay

WE KNEW THE VIRUS was on its way, burning across the world. It was going to hit Paraguay sooner or later. Infections had begun in Brazil. At the time we thought maybe we could ride out the storm. But the world was getting stormier. Then with the infections in the United States, we began getting inquiries from parents: “Where’s my daughter?” “What’s your plan?” I had traveled to the region called the Chaco — very isolated and hot, and there was the theory that the virus doesn’t like heat. That was my last trip to the field.

By March 15 it was very serious. A strange morning, overcast, leaves beginning to fall; autumn was just beginning. Walking to our office I was the only person on the street — a major thoroughfare in Asunción. People were beginning to stay at home; the government was making noises about curfews. We started preparing for lockdown. This happens to be my second evacuation in two years; in 2018 we evacuated Nicaragua — though under very different circumstances. But it’s heartbreaking to take Volunteers from their communities.

Sunday night we got the call. We had a week to get 180 Volunteers out. Paraguay is an inland island, surrounded by Brazil, Argentina, and Bolivia. Politically it was isolated for years. You fly to North America through São Paulo, Buenos Aires, or Santiago, and then another connection. We got word that Panama, a central hub to get people to the U.S., was going to close. By Wednesday word was the airport in Asunción might close. We even had a group on a bus to the airport when our travel agency canceled our tickets. So we brought people back to their hotel. Saturday, we got a chartered flight, our last large group. Lockdown began the night before; we weren’t even allowed to leave our homes to say goodbye to them. So it’s all WhatsApp, and we’re calling, we’re saying goodbye in other ways.

THREE MONTHS LATER, Latin America is being harder hit. Volunteers I speak to express gratitude to the country, sadness for leaving their communities here, but also gratitude for being close to their families in the U.S. during this time. In Paraguay, we were on strict lockdown the first month, and that helped. In Peru and Ecuador, it’s a terrible situation. Brazil is horrific. Here the population is about 7 million. We’re around 1,300 cases now; there have been 12 fatalities.

Our staff have been talking to community members and counterparts. They want everybody back. But it’s going to be a different world. In Paraguay, kissing and hugging are a big part of the culture; so is sharing food, or drinking tereré out of the same gourd or straw. That will change. If the opportunity presents itself to return Volunteers, they will be well received by their communities. But we’re going to have to think about how you go in as the foreigner who has been in a country with such high infection rates.

Another crucial factor: New and returning Volunteers alike have not only lived through an extraordinary world health catastrophe, but the recent murders of Black Americans, which are a consequence of centuries of racism, have brought another time of protest and a time of reckoning. All of us as individuals and as organizations have to look within ourselves and truly recognize that this situation — the mistreatment of people because of race — is the heritage of our country. We have to deal with it. It doesn’t mean everybody’s bad, doesn’t mean everybody’s good. It just means we’ve got to live together.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class.

When the Black Lives Matter movement began a few years ago, there were repercussions in the Peace Corps. Some wanted the agency to answer hard questions. This is now even stronger and more tragic. The economy and unemployment, the illness and who it affects most, and the reckoning with justice: It’s an extraordinary time. So our staff need to be compassionate and understanding.

I haven’t been to every country in the world, but I’ve seen a bunch. And I don’t know of any non-racist country, especially in this part of the world. Africa was colonized by Europeans who, to do what they did, dehumanized native populations. That curse has been with us ever since. In this part of the world, when we talk of Europeans — the Spanish and the Portuguese — this conquest was very violent. These nations were born in violence, but they’re trying to reckon with it.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class. Every one of us is facing uncertainties — and we’re social distancing, losing human contact. I hope compassion is what we learn out of all this. It’s not just, OK, lights are on again.

As I said to the last group flying out, when I called and they put me on speakerphone: We truly love you guys. We love you Volunteers.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thank you for reading: We try to bring you stories that matter to our community. We welcome any support you can give for the work we’re doing.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleA departure too quick — from the only Peace Corps program in the Arab world. see more

Morocco | Joshua Warzecha

Home: Clayton, California

Joshua Warzecha was an Arabic studies and linguistics major at Dartmouth College before joining Peace Corps in September 2018. He was on vacation with his family in the northern part of Morocco when he got the evacuation message and had to race back to his post in Tata, a province in the southwestern part of the country. He worked in the youth development sector, spending much of his time teaching English to teens and young adults.Back at his parents’ home in the San Francisco Bay Area, in the weeks under self-quarantine he was texting with his former students. They were sad and angry, telling him Tata is too hot for the coronavirus to survive. “A lot of ‘We miss you,’ a lot of ‘Why did you have to leave?’” he says. “We agreed the anger is more frustration.”

—Lisa Kocian for Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

Master craftsman Hamid began learning his trade 50 years ago, at age 8. Photographer and Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Dylan Thompson met him at Seffarine Square in Fez.

Read more from Morocco here:

Morocco Country Director Sue Dwyer in “This is Not a Drill.”

Volunteer Giovana Giraldo and Counterpart Omar Lyamyani in “Shoulder to Shoulder.”

This story was first published as part of “Mission, Interrupted” in Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. It also appears in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 print edition.

Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thanks for reading. And here’s how you can support the work we’re doing to help evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers.

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate... see more

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate what a herculean effort was made by PC staff to evacuate all Volunteers, safely.