Activity

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleAfghanistan at a Time of Peace traces Robin Varnum’s years as a Peace Corps Volunteer, 1971–73. see more

Afghanistan at a Time of Peace

By Robin Varnum

Peace Corps Writers

Reviewed by Jordan Simmons

Friends en route to a provincial school. Photo courtesy Robin Varnum

Afghanistan at a Time of Peace traces Robin Varnum’s years as a Peace Corps Volunteer, 1971–73. Varnum chronicles her journey into learning the place she came to call home: adapting to the chilly weather in Ghazni, southwest of Kabul, and understanding why she and other foreigners are mocked as “Mister Kachaloo” (literally, “Mr. Potato” in Dari), and traversing the length and breadth of the country — from Jalalabad to Mazar-i-sharif.

As a Volunteer she taught English to girls in grades 8–12 at Lycée Jahan Malika, the only girls school in the province. Friendships are at the center of her story — hosting dinners, trading stories, sharing wine. While navigating the male-dominated Afghan society she also does her best to build confidence in the girls she teaches, so that they might become the leaders of tomorrow. But the tomorrow that arrived was very different than the one Varnum imagined.

On July 17, 1973, near the end of Varnum’s service, her then-husband Mark, with whom she served as a Volunteer, “came home from Lycée Sanai after giving his last exam and told me there had been a coup d’état at 5:00 that morning and Afghanistan was now a republic. Mohammad Daoud Khan, a cousin of King Zahir Shah, had deposed his cousin and taken over as president. Mark said everything seemed normal at school and in the town. Nobody seemed upset.”

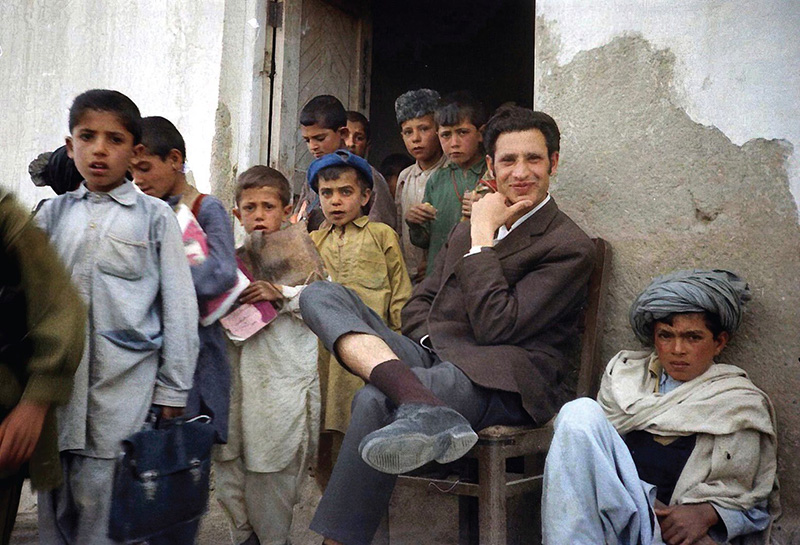

Outside a village school: Anwar, seated, served as a teacher and principal and worked with follow Volunteer Juris Zagarins. Photo by Juris Zagarins

Five years later, Daoud was overthrown and assassinated in the so-called Saur Revolution of April 1978, with factions of the Afghan communist party taking power. The U.S. Ambassador was kidnaped in 1979 and the Peace Corps program shuttered. And a cycle of suffering that has lasted generations began.

Varnum went on to teach at American International College in Springfield, Massachusetts, retiring as professor emerita.

This review appears in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of WorldView magazine.

Jordan Simmons is an intern with WorldView. He is a studying at Washington University in St. Louis.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAn excerpt from Ambika Joshee’s candid memoir, The Life of a Nepali Village Boy see more

For 30 years Ambika Joshee worked for the Peace Corps in Nepal. His memoir, The Life of a Nepali Village Boy, is a candid account of a country being transformed — and traces a personal quest for knowledge, justice, and understanding. Here is an excerpt.

An Audience with the King

By Ambika Mohan Joshee

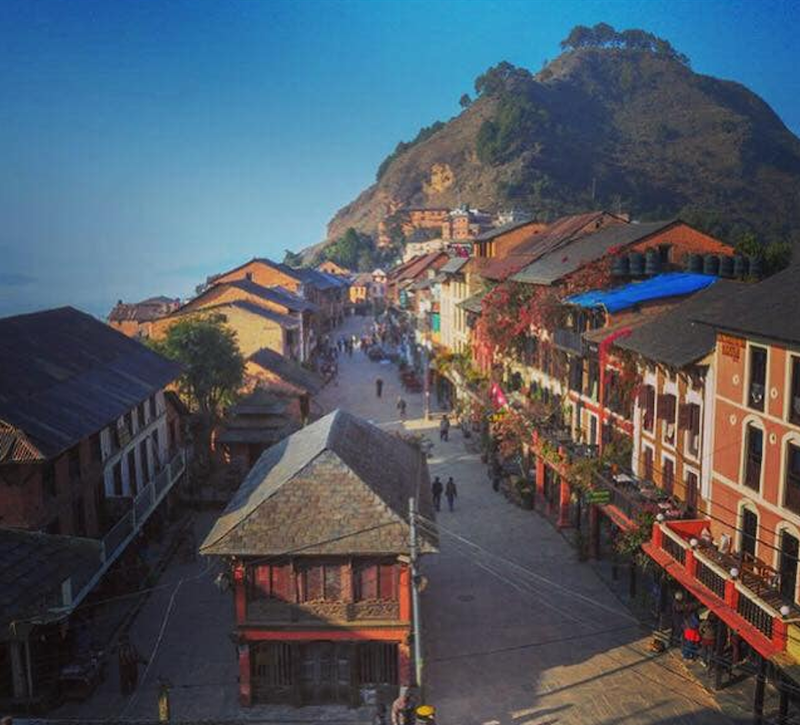

Bandipur is seven kilometers south of Dumre Bazar, which is on the Kathmandu-Pokhara highway. It is a small hilltop settlement with a population of about 16,000. About 1,030 meters above sea level, on a saddle of the Mahabharat range, it is a beautiful town with old Newari architecture. Houses have slate roofs, and the bazaar has been paved with slate. Motorized vehicles are not allowed into the town center. It is a living museum of Newari culture. The Bandipur bazaar used to be a trade center supplying merchandise to the villages of Tanahu, Lamjung, Mustang, and Manang, and the Kaski, Palpa, and Shyangja districts of western Nepal. The massive flood of 1954 forced many people from those districts, and businessmen from Bandipur settled in the flatlands of Chitawan.

The government’s transfer of the district center from Bandipur to Damauli played a vital role in encouraging the migration of Bandipures to Dumre and Damauli. The then prime minister, Surya Bahadur Thapa, took political revenge on the Bandipures by transferring the district headquarters from Bandipur to Damauli. Another blow was in building the Prithvi Highway, not through Bandipur but instead around the hill below, making it a deserted town.

Bandipur in the 1970s — a town being abandoned as it faced economic hardship and the aftermath of political revenge. Photo courtesy Ambika Joshee

Now the town is slowly developing as a hub for nearby tourist spots and as an education center with a college, two high schools, one middle school, and several elementary schools. Small agricultural and other home-based industries have begun popping up, improving the economy of the area.

While we were performing for the king, someone came onstage and told us we were being rounded up by the army — just like prisoners.

If I remember correctly, I was in sixth grade. It was just before the beginning of the Panchayat system in 1961. King Mahendra was making tours around the country. The rumor came that the king planned a visit to Bandipur; youths and schoolteachers planned a drama to show him. I was an actor in the drama — about the Revolution of 2007 BS (1951 AD) — and we used firecrackers to replicate gunfire. While we were performing for the king, someone came onstage and told us we were being rounded up by the army — just like prisoners. We had no idea that we had to ask their permission to use firecrackers because we were showing the drama to the king. The army commander came onstage and asked us many questions that we could not answer. He then realized our ignorance and let us continue. It was a new and strange experience for us.

Bandipures were and still are very much interested in and enthusiastic about education. The affluent and elite often sent their male offspring to Kathmandu; others had to depend on whatever was available there. Existing facilities were very crowded, the building dilapidated. The people realized the need for new facilities.

Hira Lall and Shyam Krishna Pradhan donated a plot of land at the foot of Gurungche danda, and construction funds were collected from local residents. The managing committee requested the king lay the foundation stone while in Bandipur for his visit.

Bandipur today — restored as a place of architectural beauty after decades of economic hardship. Photo courtesy Ambika Joshee

Around noon, the king went to the new school ground with his entourage. A fine stage was made. The place was decorated with flowers, and colored triangular flags made of paper were attached to strings. The whole town gathered. The kings were seen as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and people had the belief that one look at the king would open their door to heaven.

My hands started shaking, and I was having a problem even getting the scarf around his neck.

We had a small Nepal Scouts team at the school. The scout committee assigned me to tie a scout scarf around the king’s neck on the stage. I had never been in front of any dignitaries before. I was sweating even before I approached the stage. I had the scout scarf in my hand, and I presented the scout salute as soon as I climbed the small ladder to the stage. Then I slowly marched forward and stopped when I was just about a foot or two from the king. Everything was going as I had been taught by my teachers until I started tying the scout knot. My hands started shaking, and I was having a problem even getting the scarf around his neck. I spent about five minutes trying to make the knots, but I had no luck. He was smiling and kept quiet. He did not say a single word. He was just looking at me, which also made me nervous. After about five minutes, when the aide-de-camp general saw that I had not succeeded in tying the knot, he told me, “Just leave it. It is all right. You don’t have to tie the knot.”

Adapted from The Life of a Nepali Village Boy by Ambika Mohan Joshee © 2021, published by Peace Corps Writers.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleMeredith Pike-Baky writes on her time teaching English and living in Togo in the early 1970s. see more

Tales of Togo

A Young Woman’s Search for Home in West Africa

By Meredith Pike-Baky

Peace Corps Writers

Reviewed by Bill Preston

This candid and heartfelt memoir chronicles the twists and turns, the ups and downs, and the sometimes sideways arc of Meredith Pike-Baky’s time teaching English and living in Togo in the early 1970s. Eager to escape political turmoil in the U.S., she finds in Togo a nation “in the beginning stages of delayed independence, having declared an end to French rule a decade earlier ... on the threshold of a new era, a heady, hopeful time for both of us.”

During training in Lomé, she aspires to get “so good at French and the local languages that people wouldn’t know I was American.” She learns some humility, too — and discovers one can never completely adopt another culture as one’s own, certainly not in the short space of two years. Teaching at Collège Adèle, a Catholic secondary school for girls in the north of Togo, she enriches the curriculum with songs, games, visual aids, projects, and field trips, making English come alive for her students.

“My Togolese friends taught me the magic of storytelling in order to teach, to learn, to share."

One insight she gains: “I’d seen the universe in my small West African community. Differences were not obstacles to respect and affection.” Another, she says, is recognizing that “home wasn’t a place, a certain kind of family, a fixed professional role, or an established and protective ring of friends. It had to be a gentle urgency and quiet confidence in my seeking — trusting that each choice, despite the inevitable waves of distress, anxiety, and exclusion, would carry me forward to a sense, no matter how fleeting, of home.” And perhaps most important of all: “My Togolese friends taught me the magic of storytelling in order to teach, to learn, to share."

This review appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine.

Bill Preston served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Thailand 1977–80. This review is adapted from one originally published by Peace Corps Worldwide.

- Lynn Armstrong likes this.