Activity

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe work isn't done yet with Ukraine and returning Volunteers to service. see more

Hopeful work, as Volunteers return to serve alongside communities overseas. And crucial work to ensure Ukraine survives.

By Steven Boyd Saum

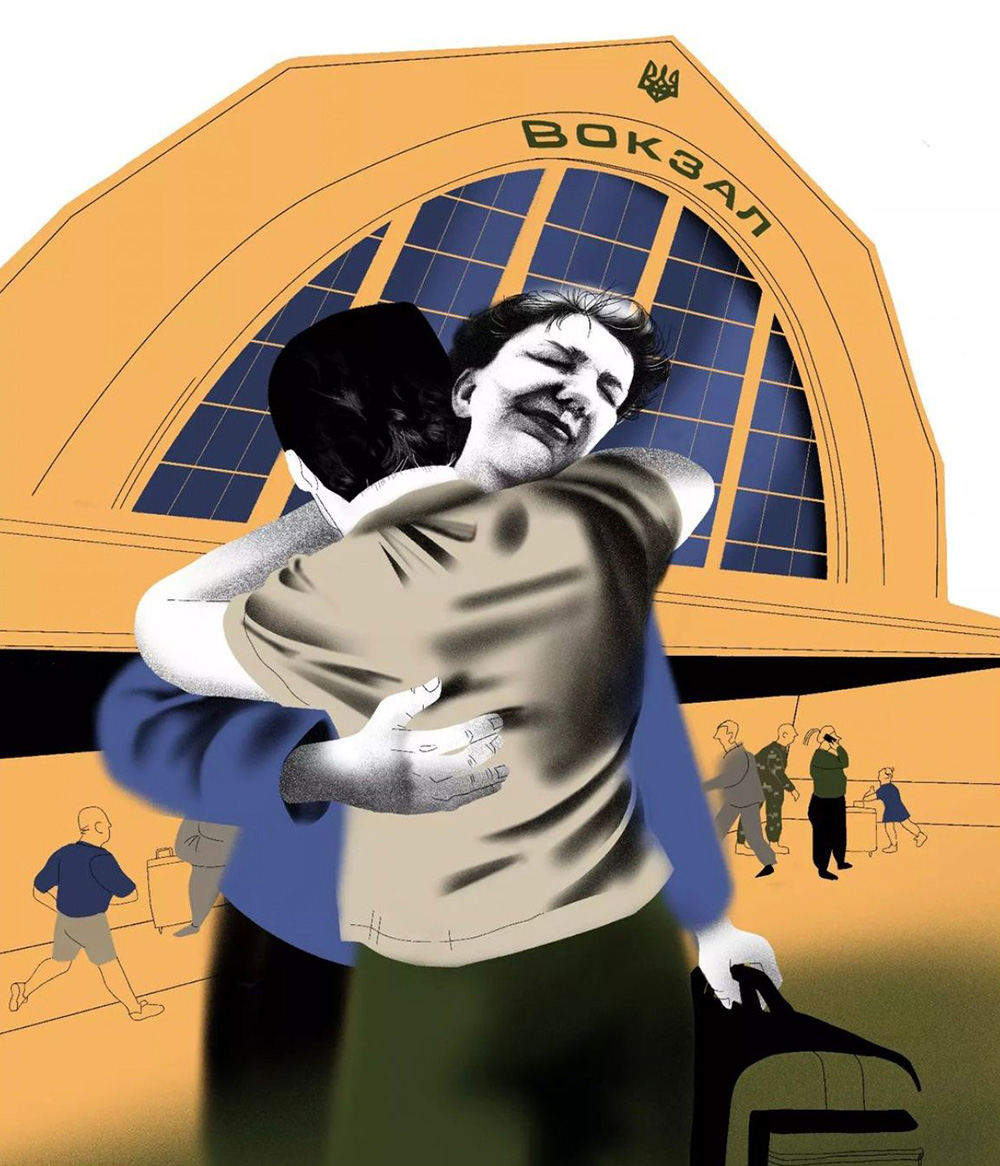

Illustration by Anna Ivanenko

For so much of the Peace Corps community, the months since March have been brimming with optimism, bringing news of Volunteers returning to service in countries and communities across the globe. In Africa, they’ve returned to countries including Zambia and Madagascar, Ghana and The Gambia, Senegal and Sierra Leone. They have returned to the Eastern Caribbean and the Dominican Republic. In Latin America, Volunteers have been welcomed in countries including Paraguay and Peru, Colombia and Costa Rica, Ecuador and Belize. In Asia, Volunteers have returned to the Kyrgyz Republic. In Europe, they’re back in Kosovo. The litany runs to some two dozen countries, and invitations are out for Volunteers to return to twice as many — as well as to launch a new program in Viet Nam.

At the same time, legislation has now been introduced in the Senate as well as the House to reauthorize the Peace Corps — and bring the most sweeping legislative reforms in a generation. That’s thanks in no small part to tremendous efforts by the Peace Corps community. All of those who took part in the Peace Corps Connect to the Future town halls and summit in 2020 played a role. Those who helped shape the community-driven report created a road map for the agency, executive branch, Congress, and the Peace Corps community. I know first-hand how hard colleagues worked as part of those efforts, some of us putting in 80- to 100-hour weeks for months on end to carry this effort forward; we understood that there would be a narrow window in Washington for these reforms to come to fruition in legislation.

That work isn’t done yet. (A familiar refrain, that. It comes with the territory for an institution charged with the mission of building peace and friendship.)

As Volunteers begin serving alongside communities once more, Europe is in the midst of its most horrific land war since 1945. The genocidal campaign launched by Russia against Ukraine continues to unfurl new atrocities day by day: In July, rockets fired on civilian infrastructure in Vinnytsia in central Ukraine — far from any front line — killed two dozen, including a young girl with Down’s syndrome. Grisly stories, photos, and videos of torture and mutilation of Ukrainian captives draw cheers from those backing the invaders.

Lies and disinformation, false accusations meant to obfuscate the truth and distract from misdeeds. As if we needed to say it, when it comes to countering those, the work isn’t done yet.

After apparently staging a mass execution of Ukrainian POWs in Olenivka, Russian disinfo serves up the claim that Ukrainian troops targeted their own. Olenivka lies just southwest of the city of Donets’k. Recall that not far to the northeast of Donets’k is where a Russian Buk missile downed the flight MH-17 in 2014, and the torrent of untruths about what had happened began.

Lies and disinformation, false accusations meant to obfuscate the truth and distract from misdeeds. As if we needed to say it, when it comes to countering those, the work isn’t done yet.

One of the cities under Russian occupation since the beginning of the war is Kherson, a port city in the south, not far from Crimea. In the wake of the 2014 Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine—which showed starkly the power of a democratic uprising as an existential threat to autocracy—I served as an observer in Kherson for the presidential election. When a polling place closes, the doors are supposed to be locked; no one is supposed to come or go until the counting is complete, the ballots wrapped up, and election protocols and ballots have been taken to the district electoral commission. It’s a good idea to come prepared with food and water to get you through a long night. The evening of that election, at the central grocery store in Kherson, just off Freedom Square, I stocked up: piroshki stuffed with cabbage and meat, along with smoked cheese, water, and some chocolate. The woman behind me was buying buckwheat, wrapped up in a clear plastic bag from the bulk foods section. She pointed at the credentials I wore on a lanyard.

“You’re an observer, yes?”

"The young people of Ukraine are smart and they deserve a chance. We need to bring an end to all this —”

I nodded.

“Thank you for being here,” she said. “We’ve been living under bandits for twenty years. They’ve all been bandits. Putin, too. He’s a bandit. It’s like slavery. The young people of Ukraine are smart and they deserve a chance. We need to bring an end to all of this—”

She waved her hands in the air over her head: the flutter and turmoil.

Railway Station: “In recent months, we have said goodbye and hello so many times,” writes illustrator Anna Ivanenko. “I don’t know how many more hugs there will be during this war, but I hope most of them will be greetings.” Illustration by Anna Ivanenko

I have thought of her often in recent months. Then, as now — and there, as well as here — one election does not make a democracy. Instead, though, what we have now is a politics of grievance in Russia that has fueled a war of aggression and lies. And the turmoil includes forced deportation of children and planned sham referenda in an attempt to expropriate yet more land and people from Ukraine.

When it comes to stopping that, the work isn’t done yet.

This essay appears in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of WorldView magazine.

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView and director of strategic communications for National Peace Corps Association. He served as a Volunteer in Ukraine 1994–96.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleVolunteers have begun to return to service. Yet millions in Ukraine are now in harm’s way. see more

Volunteers have begun to return to service. Yet millions in Ukraine are now in harm’s way.

By Glenn Blumhorst

This is a hopeful time for the Peace Corps: On March 14, a group of Volunteers arrived in Lusaka, Zambia. Just over a week later, on March 23, Volunteers arrived in the Dominican Republic. They are the first to return to service overseas since March 2020, when Volunteers were evacuated from around the globe because of COVID-19. The contributions of Volunteers serving in Zambia will include partnering with communities to focus on food security and education, along with partnering on efforts to disseminate COVID-19 mitigation information and promote access to vaccinations.

We’re thankful for the Volunteers who are helping lead the way, with the support of the Peace Corps community. And we’re deeply grateful for the work that Peace Corps Zambia staff have continued to do during the pandemic — work emblematic of the commitment Peace Corps staff around the world have shown during this unprecedented time.

Returning to Zambia: Two years after all Peace Corps Volunteers were evacuated from around the world because of COVID-19, in March the first cohort returned to begin service overseas. Photo courtesy U.S. Embassy Lusaka

Invitations are out for Volunteers to return to some 30 countries in 2022. Among those who will be serving are Volunteers who were evacuated in 2020, trainees who never had the chance to serve, and new Volunteers. Crucially, they are all returning as part of an agency that has listened to — and acted on — ideas and recommendations from the Peace Corps community for how to ensure that we’re shaping a Peace Corps that better meets the needs of a changed world. Those recommendations came out of conversations that National Peace Corps Association convened and drew together in the community-driven report “Peace Corps Connect to the Future.” We’re seeing big steps in the Peace Corps being more intentional in fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion; working with a deeper awareness of what makes for ethical storytelling; and better ensuring Volunteer safety and security.

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, NPCA has shared information and links to other ways you can help. One of the most important: Do not turn away.

At the same time, while we are buoyed by the fact that Volunteers are returning to work around the world building the person-to-person relationships in communities where they serve, we must not diminish the scale of the tragedy we are witnessing in Ukraine. More than 10 million people have fled their homes in the face of an invasion and war they did not provoke and did not want. Across this country and in Europe, thousands of returned Volunteers are working to help Ukrainians in harm’s way.

Thank you to all of you who are doing what you can in this moment of crisis: from the Friends of Moldova working to provide food, shelter, and transportation to refugees — to the RPCV Alliance for Ukraine putting together first-aid kits, leading advocacy efforts to support Ukraine, and so much more. Since the beginning of the war, NPCA has shared information and links to other ways you can help. One of the most important: Do not turn away.

Donate to the Friends of Moldova Ukraine Refugee Effort.

At a time like this it’s important to underscore a truth we know: The mission of building peace and friendship is the work of a lifetime.

That’s a message we need to drive home to Congress right now. With your support, let’s get Congress to pass the Peace Corps Reauthorization Act this year. It’s the most sweeping Peace Corps legislation in 20 years. Along with instituting further necessary reforms, it will ensure that as Volunteers return to the field it is with the support of a better and stronger Peace Corps.

President Biden will formally nominate Carol Spahn to lead the Peace Corps at a critical time.

It is becoming increasingly clear that we are entering a new era — one that desperately needs those committed to Peace Corps ideals. With that in mind, I am heartened by the news we received in early April that President Biden intends to nominate Carol Spahn to serve as the 21st Director of the Peace Corps. A returned Volunteer herself (Romania 1994–96), she began serving as acting director in January 2021 and has led the agency for the past 14 months, one of the most challenging periods in Peace Corps history.

We have been honored to work with Carol and her strong leadership team over the past year on collaborative efforts to navigate this difficult period of planning for the Peace Corps’ new future. We have full confidence in her commitment to return Volunteers to the field in a responsible manner and offer the next generation of Volunteers a better, stronger Peace Corps ready to meet the global challenges we confront. The continuity of this work is key. We are calling on the Senate to swiftly bring forth this nomination for consideration and bipartisan confirmation.

Glenn Blumhorst is president and CEO of National Peace Corps Association. He served as a Volunteer in Guatemala 1988–91. Write him: president@peacecorpsconnect.org

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe Friends of Moldova is currently spending $20,000 weekly to provide for Ukrainian families. see more

With the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Friends of Moldova has stepped in to provide crucial support to thousands of refugees.

by David Jarmul

Logo by Friends of Moldova

Until this past February, Friends of Moldova was like many “Friends of” groups within the Peace Corps community: a loose organization of returned Volunteers sharing news and supporting small grant programs in the country where they served. Then Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and everything changed.

As millions of Ukrainians fled the fighting, nearly half a million refugees came to Moldova — a small, crescent-shaped country with a population of about 3 million, bordered by Ukraine on the east and Romania on the west. Formerly occupied by the Soviet regime, Moldova itself has dealt with the reality of a breakaway enclave backed by Russian forces since the 1990s.

Within a matter of weeks of Russia’s invasion, most of the refugees who had crossed into Moldova had moved on—but more than 90,000 remained. They needed food, shelter, clothing, and more. And they needed support immediately. The Friends of Moldova raced to help. They supported the work of RPCV David Smith, who still lives in Moldova’s capital, Chişinău, and his local partner to convert their American-style barbecue restaurant, Smokehouse, into a refugee assistance center. Within days, Ukrainians lined up daily to receive free supplies.

Food and shelter: In the city of Bălți, Friends of Moldova responded quickly to help Ukrainian refugees in need. Photo courtesy Friends of Moldova

Local Peace Corps staff and others volunteered at the center. Peace Corps CEO Carol Spahn, who has since been nominated to serve as agency director, flew there from Washington, D.C., to help prepare meals. President of Moldova Maia Sandu and others also came to show their support. The PBS NewsHour and others covered this critical work. During its six weeks of operation, the center served 38,198 Ukrainians, including 7,847 individual or family walk-ins. During its last day alone it served 1,863 people.

Friends of Moldova also provided flexible funding to help Moldova for Peace, a national organization based in Chişinău, get its own operations off the ground. It assisted 175 community centers, nonprofit organizations, and shelters across the country. Funds enabled a team of volunteers to transport hundreds of Ukrainians daily from freezing conditions at the southern border to shelters around the country.

As other organizations ramped up their work in Chişinău, Friends of Moldova pivoted to open a new assistance center and programs in northern Moldova. The group’s president, RPCV Bartosz Gawarecki, left his business in Michigan to oversee the effort there. Other RPCVs joined him. Friends of Moldova members across the United States assisted as well, drawing attention to Moldova’s situation and raising more than $700,000 — an extraordinary outpouring of support. All team members with Friends of Moldova worked for free, serving the country they came to love as Peace Corps Volunteers.

The Friends of Moldova is currently spending $20,000 weekly to provide food and hygiene products to Ukrainian families and individuals across northern Moldova. Since the war began, it has assisted nearly 60,000 refugees. It cannot sustain this life-saving work without more support from fellow RPCVs and others—so it welcomes your support in this crucial work.

Learn more and donate to the Friends of Moldova on social media and at thefriendsofmoldova.com.

This story appears in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of WorldView magazine.

David Jarmul served in Moldova 2016–18 with his wife, Champa, whom he met during his initial Peace Corps service in Nepal, where he served 1977–79.

- See 1 more comment...

-

Steven Saum Read a moving essay by Sonia Scherr in this edition of WorldView as well. In "Bucha Was Home," she writes of a place where she lived and taught — with colleagues and students and a family, people... see more Read a moving essay by Sonia Scherr in this edition of WorldView as well. In "Bucha Was Home," she writes of a place where she lived and taught — with colleagues and students and a family, people who cared about her and she about them. Then the war came. www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articl...1 year ago

-

Steven Saum Raisa Alstodt and Natalia Joseph help lead the RPCV Alliance for Ukraine. In "Everything Will Be Ukraine!" they note that more than 3,400 Peace Corps Volunteers have served in Ukraine. And they... see more Raisa Alstodt and Natalia Joseph help lead the RPCV Alliance for Ukraine. In "Everything Will Be Ukraine!" they note that more than 3,400 Peace Corps Volunteers have served in Ukraine. And they offer a few ways they have sought to help the communities they served as Russian rockets fly and bombs fall across the country. www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articl...1 year ago

-

Steven Saum "Ukraine Stories" is a platform for citizen journalists, volunteers, and those working to deepen understanding of the war and efforts to help refugees. Read more about it in this story by Clary... see more "Ukraine Stories" is a platform for citizen journalists, volunteers, and those working to deepen understanding of the war and efforts to help refugees. Read more about it in this story by Clary Estes.

www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articl...1 year ago -

Steven Saum As I write in my essay for this edition of WorldView, this is a time of unfinished business for the Peace Corps community: hopeful work, as Volunteers return to serve alongside communities... see more As I write in my essay for this edition of WorldView, this is a time of unfinished business for the Peace Corps community: hopeful work, as Volunteers return to serve alongside communities overseas. And crucial work to ensure Ukraine survives. www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articl...1 year ago

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleSonja Krause Goodwin's extraordinary time in the early years of the Peace Corps see more

My Years in the Early Peace Corps

Nigeria, 1964–1965 (Volume 1)

Ethiopia, 1965–1966 (Volume 2)By Sonja Krause Goodwin

Hamilton Books

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Sonja Krause Goodwin had already traveled far from home, earned a doctorate in chemistry, and worked for six years as a physical chemist when she joined the Peace Corps. Born in St. Gall, Switzerland, in August 1933, she had fled Nazi Germany with her family and resettled in Manhattan, where her parents opened a German bookstore. Sonja entered elementary school without speaking a word of English.

Science is where she found her calling. She earned her bachelor’s in chemistry at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and her Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1957. After working six years in industry, she joined the Peace Corps and headed for Nigeria. She led the physics department at the University of Lagos until she and the other Volunteers had to leave the country in 1965 due to a politically motivated “university crisis.”

She was reassigned to teach chemistry at the Gondar Health College in Ethiopia 1965–66, a college that also served as the local hospital. On her return to the U.S., she accepted a position at RPI and taught there for 37 years, advancing through the positions of associate professor and professor, and retiring in 2004. These memoirs were published in fall 2021, shortly before Goodwin’s death on December 1, 2021.

Story updated May 2, 2022.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleMichael E. O’Hanlon’s most recent volume of strategy recommendations emphasizes restraint. see more

The Art of War in an Age of Peace

U.S. Grand Strategy and Resolute Restraint

By Michael E. O’Hanlon

Yale University Press

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Published last year, Michael E. O’Hanlon’s most recent volume of strategy recommendations for U.S. global engagement has a title that’s been overtaken by events: In this “age of peace,” Russia has launched the largest invasion of another country since World War II. The gist of O’Hanlon’s counsel is “resolute restraint” with “an equal emphasis on both words.” That means avoiding overextension without retrenchment; either would make the world less stable and more dangerous. How does that counsel square with the current U.S. grand strategy? Essentially, there hasn’t been a consensus on one since the end of the Cold War, O’Hanlon argues. That’s the problem.

“Restraint should characterize the nation’s decisions on the use of force, including whether to go to war and whether to escalate once involved in combat,” he writes. Resoluteness, in addition to defining commitments to the security interests of allies, “should also characterize the country’s commitment to a global rules-based order that promotes interdependence among nations while strongly opposing interstate conflict or the pursuit of territorial aggrandizement by other powers. We can be more patient, and accept incremental progress, on building a more liberal order (featuring more democracies and greater universal respect for human rights). The liberal or progressive agenda can and should be pursued but largely through diplomatic and other soft-power instruments of statecraft.”

But as 2022 has made clear, the Putin regime explicitly intends to upend that rules-based order.

The U.S. has a responsibility to provide leadership, O’Hanlon notes, “guided by moral principles, strong institutions in Washington and throughout the country, a supportive citizenry, and good judgment on the part of leaders.” Yet he acknowledges that governments — including that of the United States — “can still make major mistakes ... in situations characterized by sycophantic aides, groupthink, or narcissistic leaders.”

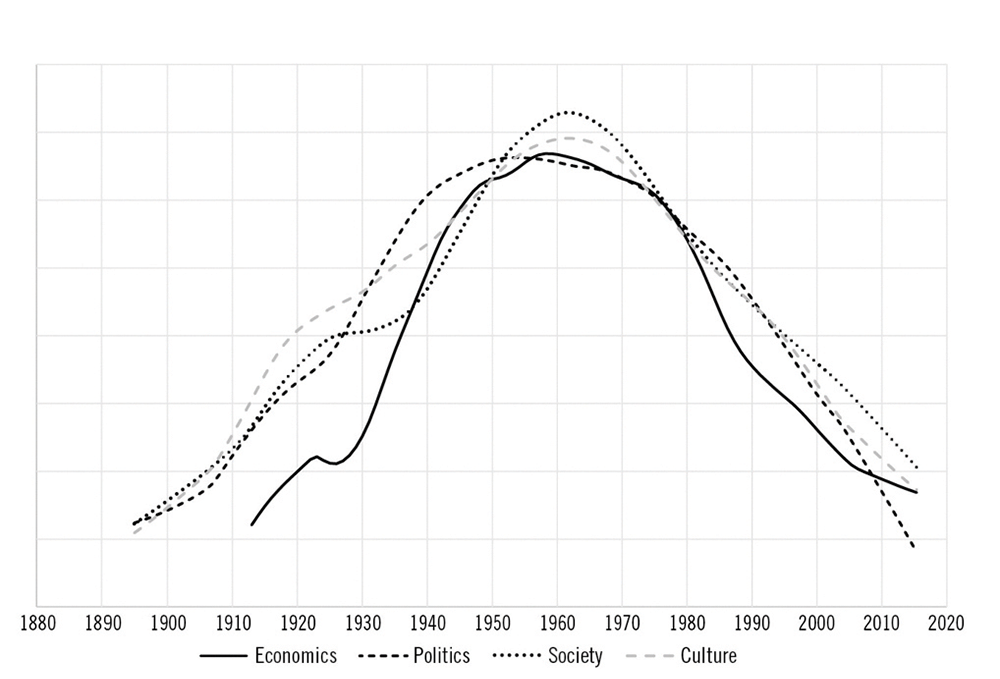

Michael O’Hanlon adds “a second dimension of 4+1 threats,” which are “nuclear, biological and pandemic, digital, climactic, and internal-societal dangers ... The last on the list is America’s own social and economic and political cohesion.”

O’Hanlon is a fellow at the Brookings Institution and served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the former Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1982–84. Writing in Foreign Affairs, Lawrence D. Freedman suggests this book “could serve as a guide for U.S. President Joe Biden’s national security team as they prepare for the challenges of the next few years.” Those challenges, as O’Hanlon outlines, include the “4+1” list the Pentagon has identified: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, and transnational violent extremism. O’Hanlon adds “a second dimension of 4+1 threats,” which are “nuclear, biological and pandemic, digital, climactic, and internal-societal dangers ... The last on the list is America’s own social and economic and political cohesion.”

That last one is the wild card in dealing with everything else on both lists. And perhaps it holds the key to whether peace can again define this new era we’re entering. Months before Putin amassed 130,00-plus troops on the borders of Ukraine, O’Hanlon assessed, “The world is becoming more dangerous again today.” Indeed, O’Hanlon has more than a little to say about Russia, and where a policy of resolute restraint might guide actions taken by the United States, NATO, and the European Union. “A strategy of deterrence by punishment can still work,” he argued, notiing, “So far at least, there are no brazen invasions of huge landmasses.”

But now there have been exactly such a brazen invasion — one that has wrought destruction unlike anything Europe has seen since the Second World War. And we have already seen atrocities that give lie to the mantra “never again.”

In the opening pages of his book, O’Hanlon cites President Kennedy’s estimation that “there could be 20 nuclear-weapons states by the mid-1960s and perhaps as many as 25 by the 1970s.” But, Hanlon notes, “Two decades into the 21st century, there are only nine countries in possession of the bomb.” One of them is of course Russia, which makes great power conflict particularly fraught. One of them used to be Ukraine — which gave up its nuclear arsenal in the mid-1990s in exchange for security and territorial assurances by the U.S. and Russia. That’s one reason, O’Hanlon and many others note, we owe a debt of gratitude — and responsibility — to Ukraine.

A shorter version of this review appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. This story was updated April 30, 2022.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity is only a demographic concept, with an emphasis on numbers see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Hermence Matsotsa-Cross

By Hermence Matsotsa-Cross

Peace Corps Volunteer in Togo 1999–2001 | Founder and CEO of Ubuntu Speaks

Below are edited excerpts. Watch the full program here.

My father was a Volunteer in Gabon in the early ’70s, where he met my mother, a Gabonese woman from one village he worked in. So I’m very much the product of Peace Corps. Growing up, I always heard Peace Corps stories; more important was the idea of volunteerism, how important that was, and working with other people to achieve goals.

I wanted to do Peace Corps after high school. My father reminded me that I had to go to college first. When I got to college, I realized that as a kinesthetic learner, four years of sitting in class was too painful. I took a year off to work with an international development organization as a reforestation volunteer in Ecuador.

My senior year I put in my application. They told me I would be going to Uzbekistan. After speaking to my father and the Peace Corps, I said, “Is there a way that I can go back to Africa?” They sent me to Togo, where I became a girl’s education empowerment Volunteer — one of only three African American volunteers in a group of 40-plus.

Training was painful; I knew I stood out because I was Black. I wanted to stand out because I was passionate about the work and being willing to learn from others. Oftentimes, it was, “You can’t be a Volunteer — you’re Black … You’re African, so you can’t go with them.” On a daily basis, I felt excluded. I felt as though Peace Corps was not supporting me. When one of the three Black Americans decided to leave during training, I was heartbroken.

Peace Corps is very much about bringing Americans to a place where they will be challenged, forced to shed misconceptions and acquire a level of cultural intelligence and cultural communication to work with people who are different.

Black Volunteers and Volunteers who are people of color are forced — to a level that white Peace Corps Volunteers may not feel — to describe the diversity that exists in the United States. Not only Volunteers but also staff did not know the history, diversity, and richness that exists within our country that makes us all Americans; therefore it was difficult for them to support us.

I realized that inclusion was essential for me to be able to do my work. I was embraced for being honest about what I didn’t know, about what I wanted to learn. Peace Corps is very much about bringing Americans to a place where they will be challenged, forced to shed misconceptions and acquire a level of cultural intelligence and cultural communication to work with people who are different.

Some ways Peace Corps can help facilitate that understanding is to be honest about what the experience may be, pre-departure: difficulties, challenges — the fact that Peace Corps staff often don’t know how to treat you or communicate with you. There needs to be mentorship for Volunteers, pre-departure and throughout service. The goal is for you to finish your experience and not come home bitter, but feeling this experience is like no other — and that you left footprints in this world to make it a better place.

Diversity is only a demographic concept — this idea that, the more numbers you have, you can say, “We’re diverse.” The effort starts at belonging.

Peace Corps can be a great model for other international organizations seeking to implement the sense of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging — and showcase to the world that we can be one in the sense that “one” means being able to see each other for who we are, and to love and respect each other for that. Diversity is only a demographic concept — this idea that, the more numbers you have, you can say, “We’re diverse.” The effort starts at belonging. There will be more people of color, more African Americans, willing to be part of Peace Corps, or any institution, if they feel they belong.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated January 19, 2022.

Hermence Matsotsa-Cross leads work incorporating the South African philosophy of Ubuntu human interconnectedness. Her organization has led projects with private and nonprofit organizations, global health and federal, state and community development programs, including the Peace Corps, CDC, and World Health Organization.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleProgress, failures, and what’s on the horizon: a conversation convened for Peace Corps Connect 2021 see more

Progress, failures, and what’s on the horizon: a conversation convened for Peace Corps Connect 2021

Illustration by Anna + Elena = Balbusso

On September 26, 2011, as the Peace Corps community marked 50 years of Volunteers serving in communities around the world, the U.S. Senate passed the Kate Puzey Peace Corps Volunteer Protection Act, which was signed into law later that year. Three years ago, Congress completed work on the Sam Farr and Nick Castle Peace Corps Reform Act. These two pieces of legislation were designed to bring about improvements and reforms pertaining to the health, safety, and security of Volunteers. What made them necessary were two tragedies: Volunteer Kate Puzey was murdered after she reported a Peace Corps employee for sexually abusing children; Volunteer Nick Castle died when he did not receive appropriate medical care in time.

National Peace Corps Association brought together this panel on September 25, 2021, to discuss progress, shortcomings, and future steps needed to further support and protect Volunteers as Peace Corps prepares for global redeployment. Below are edited excerpts.

Watch the entire discussion here: Peace Corps Safety and Security: A Decade of Legislation for Change

Susan Smith Howley, J.D.

Project Director, Center for Victim Research at Justice Research and Statistics Association

Sue Castle

Mother of fallen Volunteer Nick Castle

Casey Frazee Katz

Volunteer in South Africa 2009

Founder of First Response Action

Moderated by Maricarmen Smith-Martinez

Volunteer in Costa Rica 2006–08

Chair of the NPCA Board 2018–21

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: Issues relating to sexual assault and violence against women, and to inadequate healthcare, span the globe. Peace Corps is not immune to these challenges. We want to review the passage of laws aimed at improving and addressing challenges in Volunteer safety and health; consider how successful those laws have been in bringing about progress and change; explore where those efforts have fallen short; and consider steps to take moving forward — and identify opportunities in this unique moment.

My first foray into advocacy for Volunteer health and safety began as a member of Atlanta Area Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, after hearing Kate Puzey’s mother speak at Peace Corps 50th anniversary events in 2011. One activist who led the charge in securing the passage of the Kate Puzey Act is Casey Frazee Katz; she created First Response Action and built a grassroots movement to push this legislation forward. What did you hope to achieve?

Casey Frazee Katz: During my service as a Volunteer in South Africa, I was sexually assaulted. I found quickly that there were other Volunteers in South Africa and across the African continent and the globe who had also been sexually assaulted or harassed. What I couldn’t find were rules, laws, information, resources for someone who had been sexually assaulted as a Volunteer. So I founded First Response Action to work toward getting protections, support resources, and information codified for Volunteers.

We initially started working with Peace Corps administration. Quickly it became obvious that we needed to take a step up. We began working with legislators and pulled in other returned Volunteers and families, including Kate Puzey’s family. We drafted the initial legislation, which went through many rounds before that was signed in 2011 to codify some supports for Volunteers—and to establish victim advocacy. I’m grateful that 10 years later, victim advocacy exists within the Peace Corps. This is an issue that is ongoing. So I’m grateful NPCA is keeping this issue top of mind.

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: One outcome of that legislation was creation of the Sexual Assault Advisory Council.

Susan Howley: I was a victim advocate at the national policy level for more than 25 years, working with people around the country as they passed their first victims rights laws: the first Violence Against Women Act, then the second, then the third. Now there’s a fourth. I worked with people who helped name and develop a response to stalking and human trafficking; worked to address the DNA backlog; worked with those raising awareness and calling for change in the military, on college campuses, in churches, in youth organizations, about sexual assault. I now work in the Center for Victim Research, trying to build an evidence base for how we can better support victims and survivors. In 2012, I was part of the first Sexual Assault Advisory Council and served during its first four years.

By the time that council first met, the Peace Corps had already taken steps to stand up an office for victim advocacy; they developed and piloted their first training; there was already a risk reduction in response programming beginning to be put in place; and there were plans to research and monitor impacts. We were asked to advise on certain things; one was creation of a restricted reporting process, where Volunteers could report confidentially and access services and supports.

What struck me were the complexities involved. There’s no uniform justice system around the world. Peace Corps has no criminal jurisdiction over foreign actors. The recognition of sexual assault was far from universal.

What struck me were the complexities involved. There’s no uniform justice system around the world. Peace Corps has no criminal jurisdiction over foreign actors. The recognition of sexual assault was far from universal, especially for crimes that don’t involve penetration; certainly no uniform understanding of what sexual harassment is, or that it’s wrong. Mental health response wasn’t consistently available in countries. Unlike the military, there was no universal authority over anyone who might be involved in an assault — or response. Even where one Volunteer assaulted another, the Peace Corps didn’t have the same ability to hold someone accountable that you might have in the military. Unlike on a college campus, there are only one or two opportunities to reach the bulk of Volunteers for training. Peace Corps wanted to do a survey of RPCVs to find out more about the extent of sexual assault and harassment; that was a heavy lift, because RPCVs are no longer affiliated with the Peace Corps. You had to go through a whole process with the Office of Management and Budget before you could even think about having a survey.

How do you train in-country staff? How often do they get together? Now we’re used to doing trainings by Zoom. It was a different world 10 years ago. There were a lot of issues that came up when Peace Corps was developing things like restrictive reporting; the Inspector General didn’t understand why they didn’t automatically get all reports — even confidential. It took time for country directors to understand they could not automatically get all information about confidential or restricted reports.

With the Sexual Assault Advisory Council, each year we would come together and get a briefing on new adjustments, progress, evolutions in trainings or policies. We would hear what happened to the previous year’s recommendations: Which ones had the Peace Corps agreed with and were adopting? Which ones did the Peace Corps partially agree with? Which ones did they disagree with — and why? Then we would meet to review everything new and make recommendations.

We would help identify best practices and adapt them. But the term “best practices” is really “best that we know right now.” Often you’re pointing to a program that worked for that group in that context. Does it work here with these people? Where there were no best practices, the Peace Corps and the Sexual Assault Advisory Council relied on key principles of trying to be as transparent as possible and trying to give victims options wherever possible. You create the best trainings and policies that you can at the moment; you implement them and monitor them. Then see where things aren’t working and adjust.

I can’t think of a single area of crime victim response where advocates have been able to say, “Now we’re done. We have a system where every crime victim gets a just and compassionate response.” The most we can say in any arena is: “This is an improvement. What’s next?”

I mentioned Zoom. There are new opportunities for virtual response and training. There’s new understanding of what it means to be trauma-informed, victim-centered. You can’t have a system of continual improvement without hearing from those for whom the system is not working. There have to be systems to identify and learn from cases where risk reduction failed, or response was harmful. We have to support victims who come forward after being failed, recognize their courage, and advocate for them.

Improvements in our system of response to victims and survivors of crime in all kinds of settings, including the Peace Corps, have largely occurred because someone who was harmed or was close to someone who was harmed said, “This has to change.” Even where we make major improvements, the struggle for all of us is to recognize that “this has to change” is a repeated theme. There’s always more to do to ensure a victim-centered response and working support system. I can’t think of a single area of crime victim response where advocates have been able to say, “Now we’re done. We have a system where every crime victim gets a just and compassionate response.” The most we can say in any arena is: “This is an improvement. What’s next?”

Illustration by Anna + Elena = Balbusso

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: In addition to safety, we want to discuss healthcare for Volunteers. I first met Sue Castle several years ago through NPCA advocacy efforts; she and her husband, Dave, were working closely with members of Congress to draft and advance legislation that is now named after their son. They have been fully engaged with NPCA efforts to support it. I’ve seen firsthand the powerful impact of their story when shared with members of Congress. I’ve also seen how difficult it can be to repeat this story over and over again.

Sue Castle: I must thank everyone who has dedicated their time and effort in supporting reform efforts. Yet it’s pretty disheartening, because it is 10 years after the Kate Puzey Protection Act was signed into law, and we’re still trying to see it followed.

A month after graduating from U.C. Berkeley, in 2012, my son Nick was sent to China as a Peace Corps Volunteer. He became quite ill while serving, and he died in February 2013. Medical care he received by a Peace Corps medical officer (PCMO) was poor and contributed to his death. My primary goal in being involved in advocacy was to make sure what happened to Nick could never happen to another Volunteer. Sadly, that did not happen.

No one wants to have to share some of the worst moments of their life.

In 2018, another Volunteer, Bernice Heiderman, died due to poor medical care. Policies were not being followed. It’s heartbreaking to see this. Peace Corps is supposed to be about what is best about American service: to learn about the cultures, values, and traditions of other countries. But the Peace Corps fails when it comes to taking care of Volunteers who have had a difficult service. Volunteers who return home ill or disabled have difficulty receiving healthcare. Volunteers who are a victim of a crime or sexual assault have difficulty seeing any resolution to their case, and in receiving proper mental health services to move forward in processing their trauma. Many times these Volunteers take their case public, hoping to get help. No one wants to have to share some of the worst moments of their life.

In 2018, the Sam Farr and Nick Castle Peace Corps Reform Act was signed into law. It extends some provisions in the Kate Puzey Act. Yet some of these provisions remain vague. I’ve talked to members in Congress about that. Some issues remain confidential and are unable to be discussed — such as performance reviews of PCMOs. I want to see better healthcare in training before any growth or expansion of the Peace Corps. I want to see professional PCMOs; less encouragement to tough it out or be ignored; and a more thorough examination of the patient. I want to see medical training that reflects current standards, and reviews that accurately reflect the competency of the PCMO.

Cultural bias can be difficult to overcome. There needs to be more training in regard to that. Voices with more recent experience in regard to safety and sexual assault need to be acknowledged and not dismissed. The approach that the Peace Corps has taken has not translated into long-standing change. New ways of dealing with these issues need to be explored. The cost of advocacy is high when you have to retell your story over and over again. Peace Corps shouldn’t have to wait for a response because of a story in The Daily Beast or The New York Times or USA Today. They need to do better.

Where’s the data?

Casey Frazee Katz: When I started talking to people in my group about being assaulted, some shared that they knew of other people who had come through South Africa who had also been assaulted, or had been in other countries and medevaced to South Africa. But we didn’t have data. So I created a basic survey where I asked Volunteers to share as widely as they could, to get better data: Who had been assaulted? Which countries had hot spots or particular issues? What was the response? Do they feel supported or not? The vast majority — three-quarters of people — felt they were not supported. We were hopeful to go in the direction of the quarter of people who did feel supported: What happened there, and how are they connected? How are they resourced? Then we know what to do next.

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: Do you think that the efforts the council is taking are setting the stage for an evidence-based approach?

We were hopeful to go in the direction of the quarter of people who did feel supported: What happened there, and how are they connected? How are they resourced? Then we know what to do next.

Susan Howley: There’s always more to be done. There’s now a fully functioning RPCV survey, which will be very helpful. There’s about to be a new database that will make it easier to keep victims’ information confidential but allow pulling out more data about what happened, the kinds of responses people are getting. You still need a system that makes it comfortable for people who feel that they were failed to come forward and report — whether that’s anonymously or identifying themselves.

Just like there’s no best practice in response, there’s also no best practice in gathering this kind of data. We’ve tried national victimization surveys, local victimization surveys, college victimization surveys. There’s always a better way to improve response rates, accuracy, and understanding. The Peace Corps is about to undertake a more formal evaluation of its programs. That’s important, because one step is to try to articulate: What are the outcomes we are looking for? What are the indicators we’ll be able to gather that will show whether we are getting those outcomes? The outcomes are typically: We want people who have been victimized to thrive in the future. What is it that they might tell us is happening in the short term that is an indicator they’ll thrive in the future? You have to keep working at it and refining it.

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: If things are not documented appropriately, we are liable to repeat mistakes.

Sue Castle: What they need to do is hold people accountable for when they aren’t documenting. It tends to come out later that they did not document a safety and security or healthcare incident. There’s no accountability for not documenting. We’re going to have a new security management system. Training is critical. But I think there’s a cultural bias to dismissing some health or security concerns; that’s why they’re not documented. They need to document everything and make it clear: You’re not going to be punished for documenting, but you are going to be held accountable if you’re not documenting.

Is this a matter of needing more legislation — for example, for the Peace Corps Reauthorization Act? Or is it a matter of better implementing legislation we have passed — the Kate Puzey Act, the Farr-Castle Act? What types of measures would help support improved implementation?

The Peace Corps Reauthorization Act is a great piece of legislation. It covers a lot: increase in the workers’ compensation rate from GS 7 to 11 for RPCVs who come home and are unable to work because of a service-related illness or injury; it extends whistleblower protection; it includes the Respect for Peace Corps Act. As far as prior legislation: That shouldn’t take this long to implement.

Maricarmen Smith-Martinez: The Peace Corps Reauthorization Act would also increase the period in which Peace Corps would pay for post-service insurance from one month to three months. We saw that post-evacuation — so trying to make that permanent. The legislation proposes further reporting on post-service mental healthcare provided to returned Volunteers. What might the gradual reintroduction of Volunteers into the field mean when it comes to improving the safety and security and piloting measures?

Sue Castle: They’re already working on improving behavioral health resources for Volunteers — a good first step.

Casey Frazee Katz: What comes to my mind, especially thinking of the council working on risk reduction, is evaluating sites. I wouldn’t say that Peace Corps is inherently unsafe for anyone. Sexual assault, sadly, and sexual harassment, are issues that tend to have several commonalities. One is sometimes just opportunity. If Volunteers are in a rural area with limited cellphone reception, no independent way to get out of their site, that makes someone a little bit of a sitting duck to someone who knows that. As no Volunteers are in the field now, that gives a unique opportunity to evaluate how safe a site is, how many risk factors exist, what resources someone has access to — safety or support.

There ought to be a law. Implemented.

Casey Frazee Katz: Ten years ago, it surprised me that people we thought would be natural allies in Congress were not necessarily immediate supporters of our efforts. People were afraid that maybe we wanted, in bringing up this issue, to dismantle the Peace Corps. None of us wanted that. We believe in Peace Corps as an institution. We believe that Peace Corps does good work. We just wanted to make sure that Peace Corps was also accountable and supportive. These are reasonable measures. What Sue is talking about in terms of PCMO training is very reasonable. However, there is a pandemic and the current political climate, which can make things more challenging. In the best-case scenario, Peace Corps can be a model for supporting survivors, infrastructure, sustainability, and economy. Legislation is one part; implementation, follow-through, training, and assessment matter, too.

We just wanted to make sure that Peace Corps was also accountable and supportive. These are reasonable measures.

Sue Castle: My point has always been to make the Peace Corps better for Volunteers. I’ve done recruiting events and shared my story. I want people to be aware, but I also want people to be involved. Everybody’s voice needs to be acknowledged, whether you agree with it or not. They’re painful conversations — but necessary, and it’s only going to make the Peace Corps better.

Casey Frazee Katz: Pushing the Peace Corps Reauthorization Act forward is certainly critical. With the advocacy work we did 10 years ago, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that, in addition to the Volunteers and returned Volunteers, we were supported by a legal team who helped us prepare for the hearing and get affidavits from survivors. These are complex issues and sometimes require complex solutions.

Susan Howley: The voice of the individual is key in advocacy efforts. Legislators and policymakers tell you that they want data, facts; they want to see the logic. But it’s the real story that brings it home, that really makes that data and research come alive for a legislator and their staff — and makes them care.

WATCH THE ENTIRE DISCUSSION here: Peace Corps Safety and Security: A Decade of Legislation for Change

This story appears in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022. -

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity in the Peace Corps: It’s over 50 years and we haven’t moved the needle very far. see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Howard Dodson

By Howard Dodson

Peace Corps Volunteer in Ecuador 1964–67 | Director, Howard University Libraries

I wanted to join the Peace Corps the day Kennedy announced it was going to happen. I was a junior in undergraduate school — first on both sides of my family on the verge of graduating from college. I took the idea home to my parents. My father’s response was: “Let me see if I understand this. You’re going to finish a college degree, go away overseas for $125 a month for two years. What?” I got talked out of it the first time. The second time I decided that’s what I was going to do.

I had read The Ugly American by Lederer and Burdick, about foreign service people working overseas who were, frankly, embarrassing representations of what Americans should be. I knew I could do a better job of representing America than that.

I was offered a job teaching, and I coached a basketball team. I was the only African American in my training group — and one of about three with Peace Corps in Ecuador. But I managed to travel around South America, getting to know people of African descent. It led to my professional training and study of the African diaspora in the world. I hope that there will be opportunities for more African Americans to have meaningful, substantive experiences with peoples of African descent and others around the world, especially in this time when America’s reputation has been somewhat tarnished by our public presence in other parts of the world.

Diversity in the Peace Corps: We haven’t moved the needle very far, both at the level of staffing and Volunteers. So what is wrong with our approach? We continue to do the same things.

Diversity in the Peace Corps: It’s over 50 years that we’ve been in this conversation. We haven’t moved the needle very far, both at the level of staffing and Volunteers. So what is wrong with our approach? We continue to do the same things. I know, from my period as a Volunteer, recruiting officer, director of minority recruitment, and training officer: What we call structural racism was present in Peace Corps from day one. The solution was find three or four more people so we don’t look bad. That doesn’t solve the problem. Because of the transient nature of people’s engagement with Peace Corps as an institution, you spend two years and what you’ve gained is gone; whatever was working has not been re-created in the structure.

There were assumptions about who made good Volunteers, what you look for — and they don’t have anything to do with Black people. The diversity and inclusion framework is at the center of public conversations now. I think it gets in the way of finding real answers, because nine times out of ten they’re looking for racial representation rather than a systemic problem solver. Simply putting some Black faces in places does not change any damn thing.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Howard Dodson is the director emeritus of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which he led for 27 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity is only a demographic concept. The effort starts at belonging. see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

By Sia Barbara Kamara

Peace Corps Volunteer Liberia 1963–65 | Educational Consultant

I live in Washington, D.C. But I grew up in what would be considered public housing in North Carolina. I graduated from Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college. The Peace Corps recruiter came to campus just before graduation. I said, Yes, if I can go to Africa. I graduated with a degree in mathematics and physics, and a minor in economics. My goal was to be a scientist.

When I went to Liberia, my parents were very supportive. They always had African students at my college come home and visit. During my time in Peace Corps, when so many African countries obtained independence, every time a country changed its name, they got a new atlas. They sent Ebony magazines to me. I was way up-country, and there were four African American Volunteers in my group; by the time that magazine reached me, it was all dog-eared, because people along the way would read it.

I was a teacher and worked with young women; we created a track team, and they went on to be national champions. As a Volunteer, I had been treated like an African queen; people welcomed the Black American. But they said, “We don’t let foreigners teach below third grade.” That’s when children learn about their own culture, and they learn it from people around them. Eventually they did allow me to do it.

A life of learning: Sia Barbara Kamara with a student in Liberia, where she served with the Peace Corps. She now advises the Ministry of Education of Liberia. Photo courtesy Friends of Liberia

When I returned to the States, I served as a Peace Corps recruiter in the Northeast. Sargent Shriver would have me lead sometimes, because he thought that it was important for people of color to be seen in leadership positions. Then I served on the team recruiting at historically Black colleges. I left to become an intern in a program organized by the wife of a former Peace Corps country director in Nigeria, helping historically Black colleges obtain resources. I wrote grants to expand an early childhood program. I knew little about what I was doing, but Peace Corps gave me the courage to do almost anything. I worked with a superintendent of schools and helped organize a master’s program for African Americans to obtain degrees in early childhood education. I had the opportunity to visit early childhood programs in every Southern state and document what they were doing. I presented a paper and met the president and dean of Bank Street College in New York. They asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

The president and dean of Bank Street College in New York asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

I went on to work in North Carolina, responsible for an eight-state Head Start training program. Then I went to work for the governor of North Carolina. President Carter asked me to come work as an associate commissioner in the Department of Health and Human Services, responsible for the national Head Start program, the Appalachian Regional Commission child development programs, childcare regulations, and research and demonstration programs. Then I worked for four mayors in Washington, D.C., to help transform the early childhood system. For the last 10 years, I have been a consultant in early childhood to the Ministry of Education in Liberia. I’ve returned to that place where I got my start, working in Africa.

Early childhood educational center: Sia Barbara Kamara, right, and a sign announcing the work of a center named for her. Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

When I think about current and returned Volunteers, many need support — networking opportunities, validation, mentoring. It’s important that we continue to provide these during training and reentry, and as people are in service.

People in Liberia have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

I’m very active in our Friends of Liberia group. However, I’m the only African American in our education work group. We have been able to focus on building human capacity to help groups obtain the resources and background and know-how they need to sustain programs. People there have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

Going forward, Peace Corps needs to understand what Volunteers are experiencing during training or when they go out. I had spent four years going to jail as part of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. When we were undergoing Peace Corps training in Syracuse, New York, they didn’t want us to go and participate in a march. That was a part of my DNA. It went all the way to Washington for Sargent Shriver to have to make a decision. We marched together.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022.

Sia Barbara Ferguson Kamara received the Peace Corps Franklin H. Williams Award for Distinguished Service in 2012. At Head Start, she managed a budget of approximately $1 billion. When she started, there were 100,000 children in the program; it grew to serve 122 million under her watch.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleAsian American and Pacific Islander leaders have a conversation on Peace Corps, race, and more. see more

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity. A conversation convened as Part of Peace Corps Connect 2021.

Image by Shutterstock

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are currently the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S., but the story of the U.S. AAPI population dates back decades — and is often overlooked. As the community faces an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes and the widening income gap between the wealthiest and poorest, their role in politics and social justice is increasingly important.

The AAPI story is also complex — 22 million Asian Americans trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent, each with unique histories, cultures, languages, and other characteristics. Their unique perspectives and experiences have also played critical roles in American diplomacy across the globe.

For Peace Corps Connect 2021, we brought together three women who have served or are serving as political leaders to talk with returned Volunteer Mary Owen-Thomas. Below are edited excerpts from their conversation on September 23, 2021. Watch the entire conversation here.

Rep. Grace Meng

Member, U.S. House of Representatives, representing New York’s sixth district — the first Asian American to represent her state in Congress.

Julia Chang Bloch

Former U.S. ambassador to Nepal — the first Asian American to serve as a U.S. ambassador to any country. Founder and president of U.S.-China Education Trust. Peace Corps Volunteer in Malaysia (1964–66).

Elaine Chao

Former Director of the Peace Corps (1991–92). Former Secretary of Labor — the first Asian American to hold a cabinet-level post. Former Secretary of Transportation.

Moderated by Mary Owen-Thomas

Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines (2005–06) and secretary of the NPCA Board of Directors.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. This is not a recent story — and it’s often overlooked. I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines, and I happen to be Filipino American.

During my service, people would say, “Oh, we didn’t get a real American.” I used to think, I’m from Detroit! I’m curious if you’ve ever encountered this in your international work.

Julia Chang Bloch: With the Peace Corps, I was sent to Borneo, in Sabah, Malaysia. I was a teacher at a Chinese middle school that had been a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. The day I arrived on campus, there was a hush in the audience. I don’t speak Cantonese, but I could understand a bit, and I heard: “Why did they send us a Japanese?” I did not know the school had been a prisoner of war camp. They introduced me. I said a few words in English, then a few words in Mandarin. And they said, “Oh, she’s Chinese.”

I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised me I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.”

In Nepal, where I was ambassador, when I arrived and met the Chinese ambassador, he said, “Ah, China now has two of us.” I said, “There’s a twist, however. I am a Chinese American.” He laughed, and we became friends thereafter. On one of my trips into the western regions, where there were a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers and very poor villages, I was welcomed lavishly by one village. I heard a little girl say to her father, “You promised I could meet the American ambassador. I don’t see him.” He said to her, “There she is.” “Oh, no,” she said. “She is not the American ambassador. She’s Nepali.”

Those are examples of why AAPI representation in foreign affairs is important. We should look like America, abroad, in our embassies. We can show the world that we are in fact diverse and rich culturally.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Secretary Chao, at the Labor Department you launched the annual Asian Pacific American Federal Career Advancement Summit, and the annual Opportunity Conference. The department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics began reporting the employment data on Asians in America as a distinct category — a first. You ensured that labor law materials were translated into multiple languages, including Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean. Talk about how those came about.

Elaine Chao: Many of us have commented about the lack of diversity in top management, even in the federal government. There seems to be a bamboo ceiling — Asian Americans not breaking into the executive suite. I started the Asian Pacific American Federal Advancement Forum to equip, train, prepare Asian Americans to go into senior ranks of the federal government.

The Opportunity Conference was for communities of color, people who have traditionally been underserved in the federal government, in the federal procurement areas. Thirdly, in 2003 we finally broke out Asians and Asian American unemployment numbers for the first time. That’s how we know Asian Americans have the lowest unemployment rate. Labor laws are complicated, so we started a process translating labor laws into Asian, East Asian, and South Asian languages, so that people would understand their obligations to protect the workforce.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized.

Grace Meng: I am not a Peace Corps Volunteer, but I am honored to be here. My former legislative director, Helen Beaudreau (Georgia 2004–06, The Philippines 2010–11), is a twice-Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. I am incredibly grateful for all of your service to our country, and literally representing America at every corner of the globe.

I was born and raised here. This past year and a half has been a wake-up call for our community. Asian Americans have been discriminated against long before — starting with legislation that Congress passed, like the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Japanese American citizens being put in internment camps. We have too often been viewed as outsiders or foreigners.

I live in Queens, New York, one of the most diverse counties in the country, and still have experiences where people ask where I learned to speak English so well, or where am I really from. When I was elected to the state legislature, some of us were watching the news — a group of people fighting. One colleague turned to me and said, “Well, Grace knows karate, I’m sure she can save us.”

By the way, I don’t know karate.

We are often seen as invisible. In Congress, there are many times I’ll be in a room — and this is bipartisan, unfortunately — where people will be talking about different communities, and they literally leave AAPIs out. We are not mentioned, acknowledged, or recognized. I didn’t necessarily come to Congress just to represent the AAPI community. But there are many tables we’re sitting at, where if we did not speak up for the AAPI community, no one else would.

At the root of hate

Julia Chang Bloch: I believe at the root of this anti-Asian hate is ignorance about the AAPI community. It’s a consequence of the exclusion, erasure, and invisibility of Asian Americans in K–12 school curricula. We need to increase education about the history of anti-Asian racism, as well as contributions of Asian Americans to society. Representative Meng, you should talk about your legislation.

Grace Meng: My first legislation, when I was in the state legislature, was to work on getting Lunar New Year and Eid on public school holidays in New York City. When I was in elementary school, we got off for Rosh Hashanah; don’t get me wrong, I was thrilled to have two days off. But I had to go to school on Lunar New Year. I thought that was incredibly unfair in a city like New York. Ultimately, it changed through our mayor.

In textbooks, maybe there was a paragraph or two about how Asian Americans fit into our American history. There wasn’t much. One of my goals is to ensure that Asian American students recognize in ways that I didn’t that they are just as American as anyone else. I used to be embarrassed about my parents working in a restaurant, or that they didn’t dress like the other parents.

Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Julia Chang Bloch: I wonder about data collection. We’re categorized as AAPI — all lumped together. And data, I believe, is collected that way at the national, state, and local levels. Is there some way to disaggregate this data collection and recognize the differences?

Elaine Chao: A very good question. Data is empowering. We can’t administer government programs without understanding where they go, who receives them, how many resources are devoted to what groups.

Two obstacles stand in the way. One is resources. Unless there is thinking about how to do this in a systemic, long-term fashion, getting resources is difficult; these are expensive undertakings. Two, there’s sometimes political resistance. Pew Charitable Trust, in 2012, did an excellent job: the first major demographic study on the Asian American population in the United States. But we’re coming up on 10 years. That needs to be revisited.

Role models vs. stereotypes

Elaine Chao: Ambassador Julia Chang Bloch and Pauline Tsui started the organization Chinese American Women. I remember coming to Washington as a young pup and seeing these fantastic, empowering women. They blazed so many trails. They gave voice to Asian American women.

I come from a family of six daughters. I credit my parents for empowering their daughters from an early age. They told us that if you work hard, you can do whatever you want to do. We’ve got to offer more inspiration and be more supportive.

Julia Chang Bloch: Pauline Tsui has unfortunately passed away. She had a foundation, which gave us support to establish a series on Asian women trailblazers. Our inaugural program featured Secretary Chao and Representative Judy Chu, because it was about government and service. Our next one is focused on higher education. Our third will be on journalism.

I want, however, to leave you with this thought. The Page Act of 1875 barred women from China, Japan, and all other Asian countries from entering the United States. Why? Because the thought was they brought prostitution. The stereotyping of Asian women has been insidious and harmful to our achieving positions of authority and leadership. That’s led also to horrible stereotypes that have exoticized and sexualized Asian women. Think about the women who were killed in Atlanta.

That intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something we need to continue to combat.

Grace Meng: There was the automatic assumption, in the beginning, that they were sex workers — these stereotypes were being circulated. I had the opportunity with some of my colleagues to go to Atlanta and meet some of the victims’ families, to hear their stories. That really gave me a wake-up call. I talked about my own upbringing for the first time.

I remember when my parents, who worked in a restaurant, came to school, and they were dressed like they worked in a restaurant. I was too embarrassed to say hello. Being in Atlanta, talking to those families, made me realize the sacrifices that Asian American women at all levels have faced so that we could have the opportunity to be educated here, to get jobs, to serve our country. And that intersection of racism and misogyny that has existed for way too long is something that we need to continue to combat.

Julia Chang Bloch: We’ve talked about the sexualized, exoticized, and objectified stereotype — the Suzie Wongs and the Madame Butterflys. However, those of us here today, I think would fall into another category: the “dragon lady” stereotype. Any Asian woman of authority is classified as a dragon lady — a derogatory stereotype. Women who are powerful, but also deceitful and manipulating and cruel. Today it’s women who are authoritative and powerful.

Mary Owen-Thomas: Growing up, I was sort of embarrassed of my mom’s thick Filipino accent; she was embarrassed of it, too. I was embarrassed of the food she would send me to school with — rice, mung beans, egg rolls, and fish sauce. And people would ask, “What is that?” Talk about how your self-identity has evolved — and how you view family.

You do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Grace Meng: I don’t know if it’s related to being Asian, but I was super shy as a child. And there weren’t a lot of Asians around me. I was the type who would tremble if a teacher called on me; I would try to disappear into the walls. When I meet people who knew me in school, they say, “I cannot believe you’re in politics.”

What gave me strength was getting involved in the community, seeing as a student in high school, college, and law school that I could help people around me. After law school I started a nonprofit with some friends. We had senior citizens come in with their mail once a week, and we would help them read it. It wasn’t rocket science at all.

I tell that story to young people, because you do not need to have a fancy title to improve the lives of people around you. I became stronger myself and realized that it was my duty, my responsibility, as a daughter of immigrants, to give back to this country and to give back to this community.

Julia Chang Bloch: At some point, in most Asian American young people’s lives, you ask yourself whether you are Chinese or American — or, Mary, in your case, whether you’re Filipino or American.

I asked myself that question one year after I arrived in San Francisco from China. I was 10. I entered a forensic contest to speak on being a marginalized citizen. I won the contest, but I didn’t have the answer. At university, I found Chinese student associations I thought would be my answer to my identity. But I did not find myself fitting into the American-born Chinese groups — ABCs — or those fresh off the boat, FOBs. Increasingly, my circle of friends became predominantly white. I perceived the powerlessness of the Chinese in America. I realized that only mainstreaming would make me be able to make a difference in America.

After graduation, I joined the Peace Corps, to pursue my roots and to make a difference in the world. Teaching English at a Chinese middle school gave me the opportunity to find out once and for all whether I was Chinese or American. I think you know the answer.

My ambassadorship made me a Chinese American who straddles the East and the West. And having been a Peace Corps Volunteer, I have always believed that it was my obligation to bring China home to America, and vice versa. And that’s what I’ve been doing with the U.S.-China Education Trust since 1998.

We should say representation matters. Peace Corps matters, too.

WATCH THE ENTIRE CONVERSATION here: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Leading in a Time of Adversity

These edited remarks appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022. -

Orrin Luc posted an articleThe program you may not know that inspired JFK. And how we change what America looks like abroad. see more

The past: The program you may not know about that inspired JFK. The future: How we change what America looks like abroad.

Photo: Rep. Karen Bass, who delivered welcoming remarks for the event, part of the Ronald H. Brown Series, on September 14, 2021.

On September 14, 2021, the Constituency for Africa hosted, and National Peace Corps Association sponsored, a series of conversations on “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers.” Part of the annual Ronald H. Brown Series, the event brought together leaders in government, policy, and education, as well as some key members of the Peace Corps community.

Constituency for Africa was founded and is led by Melvin Foote, who served as a Volunteer in Eritrea and Ethiopia 1973–76. In hosting the program, he noted how the Peace Corps has played an instrumental role in training members of the U.S. diplomatic community. “Unfortunately, the number of African Americans serving in the Peace Corps has always been extremely low,” he wrote. By organizing this forum, he noted that CFA is attempting to build a community of Black Americans “who served in the Peace Corps in order to have impact on U.S. policies in Africa, in the Caribbean, and elsewhere around the world, and to form a support base for African Americans who are serving, and to encourage other young people to consider going into the Peace Corps.”

Representative Karen Bass (D-CA), Chair of the House Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health, delivered opening remarks. “I have traveled all around Africa, as I know so many of you have,” she said. “And we would love to see the Peace Corps be far more diverse than it is now. Launching this effort now, diversity and inclusion has to be a priority for all of us, including us in Congress. And we have to continue to try and reflect all of society in every facet of our lives … I am working to pass legislation to diversify even further the State Department, and looking not just on an entry level, but on a mid-career level. This effort that you’re doing today is just another aspect of the same struggle. So let me thank you for the work that you’re doing. And of course, Mel Foote as a former Peace Corps alum, and I know his daughter is in the Peace Corps. You’re just continuing a legacy and ensuring the future that the Peace Corps looks like the United States.”

“You’re continuing a legacy and making sure that in the future the Peace Corps looks like the United States.”

— Karen Bass, Member, U.S. House of Representatives

Read and Explore

The 2021 Anniversary Edition of WorldView magazine includes some keynote remarks and discussions that were part of the event.

Operation Crossroads Africa and the “Progenitors of the Peace Corps”

Reverend Dr. Jonathan Weaver | Pastor at Greater Mt. Nebo African Methodist Episcopal Church; Founder and President, Pan African Collective

An Inclusive State Department Is a National Security Imperative

Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley | Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, U.S. Department of State

Diversity and Global Credibility

Aaron Williams | Peace Corps Director 2009–12

“First Comes Belonging”

Remarks and discussion with Returned Peace Corps Volunteers Howard Dodson, Sia Barbara Kamara, and Hermence Matsotsa-Cross. Discussion moderated by Dr. Anthony Pinder.

Watch the Program

Remarks were also delivered by Melvin Foote, founder and CEO of Constituency for Africa; Glenn Blumhorst, President and CEO of National Peace Corps Association; Dr. Darlene Grant, Senior Advisor to National Peace Corps Director; and Kimberly Bassett, Secretary of State for Washington, D.C., who welcomed participants on behalf of Mayor Muriel Bowser. Watch the entire event here.

Learn More