Activity

-

Tiffany James posted an articleRecognition for three members of the Peace Corps Community. Plus a new legislator. see more

Recognition for three members of the Peace Corps community. And an RPCV appointed to the North Carolina Legislature.

By NPCA Staff

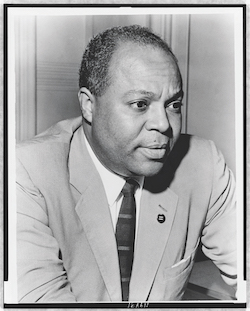

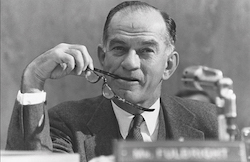

Photo: Shelton Johnson, recipient of the 2022 American Park Experience Award. Courtesy National Park Service

Shelton Johnson | Liberia 1982–83

Shelton Johnson received the 2022 American Park Experience Award for his years of advocating for diversity in national parks and helping families and youth feel welcome by seeing their stories told there. Johnson has worked for the past 35 years as a ranger with the National Park Service at Yellowstone and now Yosemite National Park. His storytelling talents landed him a prominent role in Ken Burns’ The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. In 2010, Johnson hosted Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King on a multi-day camping trip that was captured on national television and broadcast around the globe. He credits his work with Oprah as a significant breakthrough in introducing Black Americans to the wonders of America’s national parks.

Lawson Scott Glasergreen | Guatemala 1994–96

Peace Corps Volunteers have never served in Antarctica — but Lawson Scott Glasergreen, currently a FEMA contractor, celebrated what he believes to be the first Peace Corps Week there in 2015. Last year he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal by the Secretary of Defense for his work at the South Pole in 2014 and 2015, during the continent’s summer months. Glasergreen worked as a preventative maintenance coordinator and supervisor for on-site infrastructure and operation management practice and program management leadership on a Pacific Architects and Engineers contract with Lockheed Martin.

Inspired by his experience in Antarctica, Glasergreen is publishing a volume of writings and photographs. That follows on a previous book of journal entries and artworks, SPIRITO America, about the gifts of personal and social service. Glasergreen is also a visual artist and has Cherokee roots. He was among a dozen Indigenous artists featured in Native Reflections: Visual Art by American Indians of Kentucky, a traveling exhibition that completed a two-year tour of the state in Louisville in March 2022.

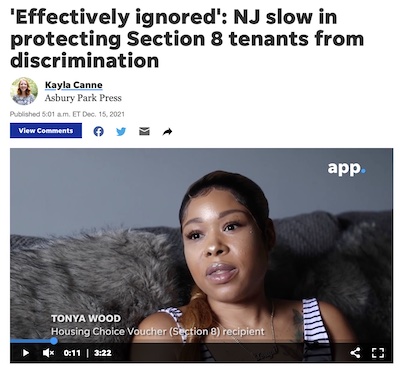

Kayla Canne | Ghana 2018–20

Journalist Kayla Canne won a National Press Foundation award for her work with the Asbury Park Press investigating deplorable living conditions and discrimination in taxpayer-funded rental housing in New Jersey. In the series “We Don’t Take That,” Canne exposed the barriers that exist for low-income tenants in their search for clean, safe, and affordable housing.

Caleb Rudow | Zambia 2012–14

Caleb Rudow was appointed by North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper to the state legislature on February 1. He is serving out the remainder of the term for Rep. Susan Fisher, who represented District 114 and stepped down December 31. The term Rudow now serves ends in January 2023. Redrawn electoral maps were unveiled February 23. The new boundaries have Rudow running for reelection next year in neighboring District 116 — in the Asheville area, like his current district. Prior to this role, Rudow worked as a research and data analyst at Open Data Watch in Washington, D.C., where he conducted research on open data funding, patterns of data use, and technical issues around open data policy.

This story appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated May 3, 2022.

-

Orrin Luc posted an article8/28/61 Peace Corps Director R. Sargent Shriver leads 80 Ghana and Tanganyika Peace Corps Volunteers see more

The legislation that permanently created the Peace Corps had yet to pass the Senate. But the Peace Corps had been launched by an executive order issued in March. And the first Volunteers were about to embark on service in Ghana and Tanganyika.

A moment in time: August 28, 1961. Founding Peace Corps Director R. Sargent Shriver leads 80 Volunteers who are headed for Ghana and Tanganyika, now Tanzania, to the White House, where President John F. Kennedy will give them a personal send-off.

JFK thanks them for embarking on their service, “on behalf of our country and, in the larger sense, as the name suggests, for the cause of peace and understanding.”

Two days later, on August 30, after a 23-hour flight from Washington, 51 Volunteers will land in Accra, Ghana, to begin their service as teachers. We’re grateful to them and the communities that have worked together with Volunteers over the past six decades. The mission of the Peace Corps, then as now, is to build peace and friendship. As if we needed reminding, that’s work far from finished.

Photograph by Rowland Scherman, Peace Corps. Courtesy the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

- Shelley Cruz likes this.

-

Brian Sekelsky posted an articleA look at the year in which the Peace Corps was founded — and the world into which it emerged see more

A look at the year in which the Peace Corps was founded with great aspirations — and the troubled world into which it emerged.

Research and editing by Jake Arce, Orrin Luc, and Steven Boyd Saum

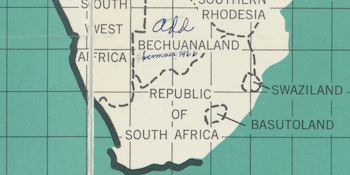

Map images throughout from 1966 map of Peace Corps in the World. Courtesy Library of Congress.

For the Peace Corps community, 1961 is a year that holds singular significance. It is the year in which the agency was created by executive order; legislation was signed creating congressional authorization and funding for the Peace Corps; and, most important, that the first Volunteers trained and began to serve in communities around the world.

But the Peace Corps did not emerge in a vacuum. The year before, 1960, became known as the Year of Africa — with 17 nations on that continent alone achieving independence. Winds of change and freedom were blowing.

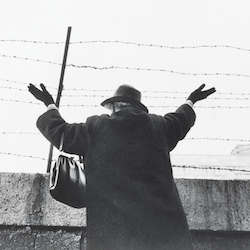

So were ominous gales of the Cold War — roaring loud with nuclear tests performed by the United States and Soviet Union. Or howling through a divided Europe, when in the middle of one August night East German soldiers began to deploy concrete barriers and miles of razor wire to make the Berlin Wall.

In May 1961, as the first Peace Corps Volunteers were preparing to begin training, across the southern United States the Freedom Riders embarked on a series of courageous efforts to end segregation on interstate transport. This effort in the epic struggle for a more just and equitable society was often met with cruelty and violence.

—SBS

January 3

Outgoing President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces that the United States has severed diplomatic relations with Cuba.

January 8

France holds referendum on independence of Algeria: 70% vote in favor.

January 9

Charlayne Hunter, left, and Hamilton Holmes become the first Black students to enroll at University of Georgia. Hunter aspires to be a journalist, Holmes a doctor. White students riot, trying to drive out Hunter and Holmes. A decade before, Horace Ward, who is also Black, unsuccessfully sought admission to the law school.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault indeed goes on to become a journalist and foreign correspondent for National Public Radio, CNN, and the Public Broadcasting Service.

Hamilton Holmes goes on to become the first African-American student to attend the Emory University School of Medicine, where he earns an M.D. in 1967, and later serves as a professor of orthopedics and associate dean.

January 17

President Eisenhower’s farewell address. Warns of the increasing power of a “military-industrial complex.”

January 17

REPUBLIC OF CONGO: Patrice Lumumba, who had led his nationalist party to victory in 1960 and was assessed by the CIA to be “another Castro,” is assassinated — though this won’t be known for weeks.

January 20

JFK’s inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you ...”

Read annotations on the address 60 years later in our winter 2021 edition.

January 21

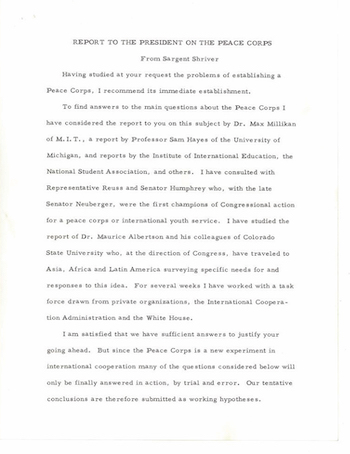

JFK asks Sargent Shriver to form a presidential task force “to report how the Peace Corps should be organized and then to organize it.”

Shriver taps Harris Wofford to coordinate plans.

February

ANGOLA: Start of fighting to gain independence from Portuguese colonial rule. February 4 will come to be marked as liberation day.

February 5

State Department colleagues Bill Josephson and Warren Wiggins deliver a paper to Shriver they call “The Towering Task.”

It lays out ideas for establishing a Peace Corps on a big, bold scale. Within three weeks, Shriver lands a report on JFK’s desk, saying with go-ahead, “We can be in business Monday morning.”

February 9

Debut appearance by the Beatles at the Cavern Club in Liverpool

February 12

USSR launches Venera 1 — first craft to fly past Venus.

February 27

Aretha Franklin releases first studio album: “Aretha with the Ray Bryant Combo.”

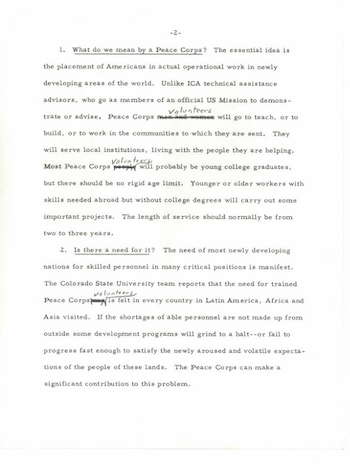

March 1

Executive Order 10924: JFK establishes the Peace Corps on a temporary pilot basis.

He says, “It is designed to permit our people to exercise more fully their responsibilities in the great common cause of world development.”

March 4

JFK announces Sargent Shriver will serve as first Director of the Peace Corps.

March 6

Executive order 10925: creates President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. Government contractors must “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” First use of phrase “affirmative action” in executive order.

March 14

Bill Moyers, a 26-year-old legislative assistant to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, takes on responsibilities as special consultant to the Peace Corps. The project, Moyers believes, shows “America as a social enterprise ... of caring and cooperative people.”

March 18

ALGERIA: Cease-fire takes effect in War of Independence from France.

March 29

23rd Amendment ratified. Allows residents of Washington, D.C. to vote in presidential elections for the first time.

April 11

Trial of the century — of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, architect of Hitler’s “Final Solution of the Jewish question” — begins in Jerusalem.

April 12

Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes first human being to travel into space. In Vostok I, he completes an orbit of the Earth.

April 17

CUBA: U.S.-backed invasion at Bay of Pigs attempts to overthrow Fidel Castro. Invading troops surrender in less than 24 hours after being pinned down and outnumbered.

April 22

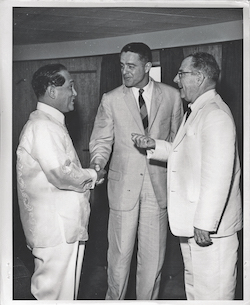

Sargent Shriver embarks on a “Round the World” trip to pitch the Peace Corps to global leaders. With him: Harris Wofford, Franklin Williams, and Ed Bayley.

They visit Ghana, Nigeria, India, Pakistan, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

April 27

SIERRA LEONE gains independence following over 150 years’ British colonial rule. Milton Margai serves as prime minister until his death in 1964.

April 29

World Wildlife Fund for Nature established in Europe. Focuses on environmental preservation and protection of endangered species worldwide.

May 4

Freedom Riders: Civil rights activist James Farmer organizes series of protests against segregation policies on interstate transportation in southern U.S. Buses carrying the Freedom Riders are firebombed, riders attacked by KKK and police, and riders arrested.

Four hundred federal marshals are then sent out to enforce desegregation.

May 5

First U.S. astronaut flies into space: Alan Shepard Jr. on Freedom 7.

May 11

VIETNAM: JFK approves orders to send 400 special forces and 100 other military advisers to train groups to fight Viet Cong guerrillas in South Vietnam.

May 15

First Peace Corps placement test administered

May 21

Senate Foreign Relations Committee confirms Shriver as Director of the Peace Corps.

May 22

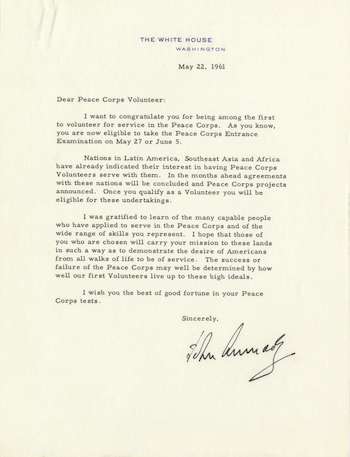

Dear Peace Corps Volunteer: First Volunteers receive letters from President Kennedy inviting them to join the new Peace Corps.

May 25

Space race: Addressing joint session of Congress, JFK says: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

May 25

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC: Dictator Rafael Trujillo, who has ruled since 1930, is assassinated following internal armed resistance against his oppressive regime.

May 31

SOUTH AFRICA: Following a white-only referendum, the government of the Union of South Africa leaves the British Commonwealth and becomes an independent republic.

June 4

JFK meets Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev over two days in Vienna. “Worst thing in my life,” JFK tells a New York Times reporter. “He savaged me.”

June 6

ETHIOPIA: In the Karakore region, a magnitude 6.5 earth-quake strikes. Thirty people die.

June 22

Peace Corps has received “11,000 completed applications” in the first few months, Shriver tells Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

June 25

Training begins for Peace Corps Volunteers for Tanganyika I and Colombia I at universities and private agencies in New Jersey, Texas, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere.

July

Amnesty International founded in the United Kingdom to support human rights and promote global justice and freedom.

August 3

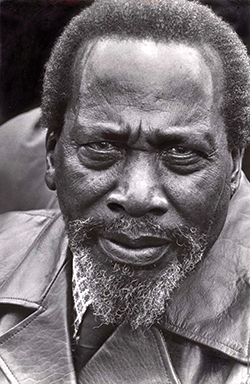

Arkansas Democrat Sen. William Fulbright, skeptical of Peace Corps’ effectiveness, is cited in The New York Times as calling for a budget one-fourth the amount requested.

August 4

Sargent Shriver testifies in the House of Representatives and faces hostile GOP questioning. Meanwhile, in the Senate, the Fulbright-led Foreign Relations Committee votes 14–0 to authorize the Peace Corps with the full $40 million in funding requested.

August 4

Barack Obama born in Honolulu, Hawaii. In 2008 he becomes first African American president and 44th president of the United States.

August 6

Vostok 2: Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov becomes second human to orbit the Earth — and first in space for more than one day.

August 10

JFK press conference: “We have an opportunity if the amount requested by the Peace Corps is approved by Congress, of having 2,700 Volunteers serving the cause of peace in fiscal year 1962.” By the end of 1962, there will be 2,940 Volunteers serving.

August 13

Berlin Wall: In the middle of the night, East German soldiers begin stringing up some 30 miles ofbarbed wire and start enforcing the separation between East and West Berlin.

August 17

Charter for the Alliance for Progress signed in Uruguay, to bolster U.S. ties with Latin America. JFK compares it to the Marshall Plan, but the funding is nowhere near that scale.

August 21

KENYA: Anti-colonial activist Jomo Kenyatta released from prison after serving nearly nine years. In 1964 he becomes president of Kenya.

August 25

Senate passes the Peace Corps Act.

August 28

Rose Garden send-off: President Kennedy hosts a ceremony for the first groups of Volunteers departing for service in Ghana and Tanganyika.

August 30

After a 23-hour charter Pan Am flight from Washington, 51 Volunteers land in Accra, Ghana, to begin their service as teachers.

August 30

In Atlanta, Georgia, nine Black children begin classes at four previously all-white high schools. The city’s public schools had been segregated for more than a century.

September 1

ERITREA: War of Independence begins with Battle of Adal, when Hamid Idris Awate and companions fire shots against the occupying Ethiopian army and police.

September 4

Foreign Assistance Act enacted, reorganizing U.S. programs to create the new U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which officially comes into being in November.

September 6

Drawing a bright line, official policy declares Peace Corps will not be affiliated in any way with intelligence or espionage.

September 8

First group of 62 Volunteers arrive in Bogotá, Colombia, aboard a chartered Avianca flight. They are referred to as “los hijos de Kennedy”—Kennedy’s children.

September 14

House passes the Peace Corps Act 288–97.

September 18

United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld dies in a plane crash en route to a peacekeeping mission in the Congo. He is posthumously awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

September 22

House and Senate bills reconciled: JFK signs the Peace Corps Act into law. The mandate: “promote world peace and friendship.”

September 30

First group of 44 Volunteers arrive in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika. They include surveyors, geologists, and civil engineers to work with local technicians to build roads.

October 14

Postcard from Nigeria: Volunteer Margery Michelmore sends a postcard to her boyfriend describing her first impressions of the city of Ibadan, calling conditions “primitive.” The card doesn’t make it stateside. Nigerian students mimeograph and distribute it widely on campus; it is front-page news in Nigeria and beyond. Michelmore cables Shriver that it would be best if she were removed from Nigeria. She is.

October 18

Jets vs. Sharks: Premiere of film adaptation of musical “West Side Story.” A hit at the box office, it will win 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

October 30

Doomsday Device: Soviet Union tests the Tsar Bomba, largest explosion ever created by humankind. Its destructive capabilities make it too catastrophic for wartime use. International condemnation ensues. U.S. has begun its own underground testing.

November 9

GHANA: U.K.’s Queen Elizabeth visits to meet with President Kwame Nkrumah.

November 24

World Food Programme is established as a temporary United Nations effort. The first major crisis it meets: Iran’s 1962 earthquake. In 2020 its work is recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize.

November 28

Postcard postscript: Nigerian Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa gives a warm welcome to the second group of Peace Corps Volunteers.

December 6

Ernie Davis of Syracuse University becomes the first Black player to win college football’s Heisman Trophy. Leukemia will tragically cut his life short 18 months later.

December 9

TANGANYIKA declares independence from the British Commonwealth. In 1964 country name becomes Tanzania.

December 14

Executive Order 10980: JFK establishes Commission on the Status of Women, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, to examine discrimination against women and how to eliminate it. Issues addressed include equal pay, jury service, business ownership, and access to education.

December 31

500+ Peace Corps Volunteers are serving in nine host countries: Chile, Colombia, Ghana, India, Nigeria, the Philippines, St. Lucia, Tanganyika, and Pakistan. An additional 200+ Americans are in training in the United States.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe globe in 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers see more

In 1961, nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers.

THE GLOBE IN 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers — and the year after 17 nations in Africa gained independence. For the first Peace Corps programs, demand is strongest for teachers and agricultural workers. Volunteers are urged to embark on their journey in the spirit of learning rather than teaching. To lay the groundwork, Sargent Shriver, the first Director of the Peace Corps, undertakes a round-the-world trip to eight nations from April to May.

Photos by Brett Simison. Words by Jake Arce and Steven Boyd Saum

St. Lucia, an island in the Eastern Caribbean, is the third program to host Volunteers: 16 train at Iowa State University and arrive in September. The island will gain independence from the British Commonwealth in 1979.

Volunteers arrive in Colombia on September 8: All are men, ages 19 to 31. The endeavor involves a partnership with CARE. Some work in community development with the Federation of Coffee Growers, some in the Cauca River Valley in the southwest.

In Chile, 42 Volunteers train to provide assistance in community development and education as part of the Chilean Institute of Rural Education, a nonsectarian private organization. They're in service by October, working with Chilean educators in developing programs in hygiene, recreation, and farming.

Shriver tours Latin America in October. Four countries sign agreements to host Volunteers in 1962. In Brazil Volunteers will work in rural education, sanitation, and health, and in poor urban areas in the northeast. In Peru they will work in indigenous highlands and impoverished urban areas. In Venezuela, work will include teaching at a university and as county agricultural agents. Bolivia asks for engineers, nurses, dental hygienists, and food educators.

Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah speaks at the U.N. and meets JFK in March. Shriver visits him in April — not long after the Ghanaian Times denounces the nascent Peace Corps as an “agency of neo-colonialism.” But after hearing Shriver, Nkrumah says, “The Peace Corps sounds good. We are ready to try it and will invite a small number of volunteers ... Can you get them here by August?” They arrive August 30, the first Volunteers in service.

President of the Philippines Carlos B. Garcia has pursued a Filipino First policy, noting, “Politically we became independent since 1946, but economically we are still semi-colonial.” The final stop on Shriver's spring round-the-world tour, the country welcomes 128 Volunteers in October to supplement teaching in rural areas, focusing on English and science.

Nigeria gained independence from Britain on October 1, 1960. Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa asks Shriver to send teachers; the country has only 14,000 classroom slots for more than 2 million school-age children. First Volunteers arrive by end of September.

India, a country of half a billion people, is led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru — de facto leader of the nonaligned nations, those allied with neither the United States nor USSR. When Shriver visits in spring 1961, Nehru is skeptical but allows, “In matters of the spirit, I am sure young Americans would learn a good deal in this country and it could be an important experience for them.” He agrees to host a small number of Volunteers in Punjab. A cohort of 26 arrives December 20. After India agrees to host Volunteers, so do Pakistan, Thailand, and Malaya.

Pakistan’s President Mohammad Ayub Khan came to power in a coup in 1958 and was elected by a referendum in 1960. Addressing the U.S. Congress in July 1961, he calls for more financial assistance. The first group of Volunteers arrives in West Pakistan in the fall to serve are junior instructors at colleges, as well as teachers of farming methods and staff at hospitals.

First Volunteers arrive in Tanganyika on September 30: civil engineers, geologists, and surveyors, there to build roads and create geological maps. The country is a U.N. trusteeship that achieves full independence in December. Also note: in October, 26 Volunteers begin training for service in Sierra Leone in 1962.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleAnd a conversation on Peace Corps ideals in today’s world see more

Williams issues a clarion call for building a more inclusive network for global development. And he explores the arc of Peace Corps history in an interview about the documentary A Towering Task.

By Del Wood and Steven Boyd Saum

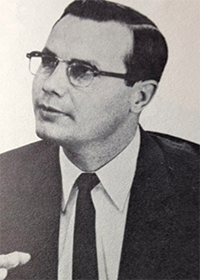

We are in an historic moment. The protests against racial injustice that have swept the United States and scores of other countries since the end of May were sparked by the killing of George Floyd — one of so many Black women and men killed by police. The protests erupted with anger and frustration — and not only among Blacks. They have also ushered in the possibility of the United States coming to terms with systemic racism. That transformation needs to be carried over into global development work, writes former Peace Corps Director Aaron Williams.

“The diversity of the demonstrators gives me great hope that this could be the pivotal moment in our nation,” Williams observes in an essay published by Devex in June. “They are demanding that we live up to the American dream, and the ideals of democracy, civil rights, liberty, opportunity, and equality that the country was founded on two centuries ago.”

Williams also argues that international organizations have a responsibility to transform how they do their work:

“U.S. international and foreign affairs organizations should rise to this challenge, and seize this moment to demonstrate leadership in pursuing broad-based policies and programs that will promote diversity and social justice in both their U.S. and overseas offices. They play a prominent role — as principal partners with the U.S. government — in the country’s global leadership, and thus should invest in the diverse human capital of the future that will mirror the true face of our country.”

Williams served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Dominican Republic from 1967 to 1970 and as Director of the Peace Corps from 2009 to 2012. Read the full essay here.

‘Transformed my life’: Aaron Williams on Peace Corps history and A Towering Task

With the screening of A Towering Task: The Story of the Peace Corps in Florida recently, Aaron Williams sat down for a conversation about the film. He supplements the sweeping history of the Peace Corps in the documentary with personal stories. How he, as a young Black man from the South Side of Chicago, headed into Peace Corps with a nearly all-white cohort of Volunteers. Of the powerful impact Peace Corps had in Ghana — teaching a young man and inspiring him to become a scientist, then later vice president and president. And he makes the case for Peace Corps ideals as offering a way forward: with understanding what it means to be engaged with the world, and to live out those ideals at home.Here are clips from the conversation with film exhibitor Nat Chediak.

“My entire career … whether I've been in business, I’ve been in government, I’ve been in the nonprofit world — Peace Corps was the trigger for that.”

WILLIAMS: Well, first of all, so I grew up in a working-class family on the South Side of Chicago. I was the first person in my family to graduate from college, and people expected me to settle down, become a teacher and, you know, have a normal life. Well, I had become intrigued by the Peace Corps by listening to Sargent Shriver’s speeches. And I heard a couple of Kennedy’s speeches. I was still pretty young when Kennedy was president. But I decided, this is something that I should look into. It sounded like something that would be structured, would give me a chance to learn something about outside of the United States, and it turned out to be the adventure of a lifetime. I mean, truly, truly transformed my life. Everything that I’ve done, Nat, has emanated from the Peace Corps. My entire career … whether I've been in business, I’ve been in government, I’ve been in the nonprofit world — Peace Corps was the trigger for that.

The other thing about the Peace Corps is that when I arrived out in California, the San Diego State College where I was trained, I was in a group of about 80 or 90 people. I was the only Black person in the group. And I was wondering to myself, those first couple of days, what have I parachuted myself into? I quickly found out, within a week or two weeks there, that I was in the presence of some very special people. People who had self-selected to join in this wonderful enterprise called the Peace Corps, who were interested in making the world a better place, and were open to ideas, to people, to thoughts, and philosophies. That was just amazing. So it was an amazing time. And I trained with some amazing people. Part of our group went to El Salvador, part went to Honduras, the other part went to the Dominican Republic, and we were teacher trainers. So that's how it all emanated. That’s how I ended up in the Peace Corps.

“And that’s when this young man who became vice president, and ultimately president of Ghana, decided he wanted to become a scientist.”

WILLIAMS: There’s also a great commonality. And that’s what you really learn in the Peace Corps, right? You learn about the commonality and things that we worry about: our children, the future, good healthcare, aspirations for our children and our family. And you learn that those are the basic common elements that we all share, no matter where you might be born or live on the globe.

Let me tell you a story. I was in Ghana to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Peace Corps. And I went to an event with the then-vice president of Ghana. He had been taught by a Peace Corps Volunteer when he was a young man in elementary school in a remote part of Ghana. Ghana was one of the first countries where Sargent Shriver established the Peace Corps in 1961. So when we arrived at this event, it was to celebrate the Year of the Teacher in Ghana. And a Peace Corps Volunteer was one of the ten top teachers that was being honored, as a matter of fact. And that Peace Corps Volunteer, by the way, her parents had served as Peace Corps Volunteers in Latin America, you know, years before — so what a marvelous confluence of events. As I was waiting in the government house in this regional city to go out to the event with the vice president, I had a couple of talking points I wanted to share with him about the future of the Peace Corps in Ghana and some things that the ambassador had asked me to share with the vice president. And instead, he wanted to tell me a story about how he met this Peace Corps Volunteer.

So he’s a young man in this classroom. They had never seen a white person before in the village, and they were worried about this new teacher they had heard about. They wondered, would this man even speak English? Could they understand him? What was this gonna be all about? He comes in and he says: How many people here in this room know how far the sun is from the Earth? And they’re thinking, why is he asking us this? Who knows the answer to this question? Everybody put their heads down, nobody answered. He went up to the board and he wrote on the board: “93.” Then he went around this one-room classroom — with these chalk balls — and he kept circling with chalk until he came back around to the front. He says, “Ninety-three million miles. Don’t you ever forget that.”

“And that’s when this young man who became vice president, and ultimately president of Ghana, decided he wanted to become a scientist.”

WILLIAMS: He could have told me anything that day, but that’s the story that he shared with me, which I have never forgotten. It was such a stunning, amazing — and it tells you a lot about the impact of the Peace Corps. Now, lastly, when I got back to the States I did everything I could see if we could find this volunteer who had taught him. And we did!

CHEDIAK: No kidding!

WILLIAMS: When he came over for a summit of African nations with President Obama, we arranged a reunion with the then-vice president and the Peace Corps Volunteer who taught him in Ghana in that rural school.

CHEDIAK: You're kidding. Were you there? Was it very emotional?

WILLIAMS: No, I was not there.

CHEDIAK: Ah, okay. Okay, but I can imagine now I'm, you know, what a beautiful moment that must have been for both of them.

CHEDIAK: Oh, my gosh, that’s incredible. That’s a beautiful story.

WILLIAMS: It’s a miracle they tracked him down. This is 50 years later.

“That’s what we bring to the rich tapestry of America when we return home."

CHEDIAK: Even in these difficult, nationalistic days — and I’m not talking simply about the U.S. — you know, but it’s something that we have seen in other countries that is a troubling concern. You still feel that the goodwill of men will prevail?

WILLIAMS: I think so, and I think the Peace Corps is really my foundation for believing that. Because I’ve seen people prevail against really tough situations — horrendous conditions, right? Fighting disease, fighting poverty, political unrest, civil war, and they come out the other side, in most cases, better than they were in the beginning. Not in all cases, right — but it happens. So, that’s the reason I continue to be optimistic about the future of the world and mankind. And I’m so proud of Peace Corps Volunteers who have served for almost 60 years in countries around the world, who represent the true face of America and who really understand what it means to be engaged with the rest of the world and to become effective and optimistic global citizens. That’s what we bring to the rich tapestry of America when we return home and what we do in our future careers here at home.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA remembrance of Paul Johnson see more

A remembrance of Paul Johnson

By Jake Arce

Paul Johnson understood what it means to tend the earth. He was a farmer and a state and national leader in the movement to conserve soil and water. As chief of the Natural Resources Conservation Service, he led the agency to produce a national report card on the state of America’s private lands. He called it “A Geography of Hope.”

Johnson joined the Peace Corps in 1962, serving in one of the first groups in Ghana. After returning to the United States in 1964, he completed studies in natural development, earning a master’s in forestry at the University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources. He married an RPCV from the Philippines, Patricia Joslyn, in 1965; they later traveled together to teach in Ghana’s School of Forestry and started a family abroad.

“The foundation of our farm’s productivity is our soil, a complex, living system that, although largely unrecognized as important in our national environmental policies, is in fact the basis of all life.”

They settled in Iowa in the 1980s. Of his land there Johnson once wrote, “The foundation of our farm’s productivity is our soil, a complex, living system that, although largely unrecognized as important in our national environmental policies, is in fact the basis of all life. If we farm our soil well, its productivity will be sustained by recycling what was once living into new life.”

He was elected to the Iowa State House of Representatives and served three terms. He co-wrote the Iowa Groundwater Protection Act to stop contamination from surface pollutants and underground tanks. He garnered bipartisan support for progressive action on the environment and crafted Iowa’s Resource Enhancement and Protection program, funding parks, trails, and wildlife enhancement.

He also knew what was not enough. Speaking to the Des Moines Register in 2000, he said: “A land comprised of wilderness islands at one extreme and urban islands at the other, with vast food and fiber factories in between, does not constitute a geography of hope.” He died in February at age 79.

- Mary Novotny likes this.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleFirst director of the Africa Regional Office for Peace Corps — and counselor to Nelson Mandela see more

By Jonathan Pearson and Steven Boyd Saum

Richard Paul Thornell was only 24 years old when Sargent Shriver and Harris Wofford sent him to Ghana as director of the Peace Corps Africa Regional Office. “For him, it was a lifelong sense of pride,” his son Paul Thornell told the Washington Post. “The Peace Corps is the thing that has lasted, in a meaningful way, longer than other things, and the fact that my dad had a central role in launching it, that meant a lot to him.”

Yet that was only one of the groundbreaking roles Richard Paul Thornell played. A graduate of Fisk University, he became the second Black graduate of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. Along with Peace Corps, Thornell served in the U.S. Army and the U.S. Agency for International Development. A law degree from Yale University soon led him to Howard University, where he taught hundreds of future lawyers over a 30-year career. With the end of apartheid in South Africa and the election of Nelson Mandela, Thornell helped launch a partnership between Howard University and South Africa. This partnership included counsel to President Mandela and assistance with a new constitution.

Enduring commitment: Richard Paul Thornell and wife Carolyn Atkinson. Photos courtesy Paul Thornell

Among his many other contributions, Thornell served on the Board of Trustees at Fisk University, general counsel at Howard, special counsel to the Washington bureau of the NAACP, vice chair and counsel of the board of directors of Africare, and member of the board of directors of the YMCA of Metropolitan Washington.

He and Carolyn Atkinson Thornell enjoyed nearly half a century of marriage together. He was born in 1936 and died April 28, 2020, at the age of 83 after he contracted COVID-19. The family plans to hold memorial services when people can gather to celebrate his life and legacy.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleFive country directors tell the stories of Peace Corps evacuation. see more

When times are good, being a country director for Peace Corps may be the best job in foreign affairs. This has not been such a time.

As told to Steven Boyd Saum

Photo: Vyshyvanka Day, when schoolchildren don the traditional Ukrainian shirt — and here, pose as one. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Kim Mansaray | Country Director, Mongolia

JANUARY AND NEWS OF THE VIRUS came out in China. Mongolia says we’re not sending kids back to school. Our winter break became endless winter break. Then the virus exploded in China, and Mongolia went on hardcore lockdown — borders and flights.

From time to time in Mongolia, there’s an outbreak of something, then a quarantine — fairly routine. That was on our minds: Watch how this plays out. The clincher was when flights from Seoul were canceled. I talked to the embassy and said, If people need to be medically evacuated, we’re not gonna be able to get them out.

The farthest part of the country is normally a 40-hour bus ride. It took five days with help from embassy cars to caravan all Volunteers back in. And of course, because it’s Mongolia, there was a blizzard.

Volunteers just a few months in were put on administrative hold. Then, in mid-March, Washington moved everybody to Close of Service. My Volunteers were giving me grief. I said, I get your frustration and your anger. But this is unchartered territory for Peace Corps.

Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the volunteers back as soon as possible.”

Mongolia on horseback. Photo by Antonio Mercatante

Fast forward to June: Our staff in Mongolia have been out and about and in the countryside, visiting potential sites, picking up luggage that Volunteers left behind. And making honest assessments: Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the Volunteers back as soon as possible.” There’s a real connection. Volunteers are staying in touch with communities. Mongolia is incredibly wired; they use Facebook for everything.

Here, they see what’s happening in the U.S. Three, four days a week, people come in my office and ask: “What is going on?” Diplomatically I say, “Our democracy is right out there for you to see. It’s messy and it’s ugly, and it’s been tough.” But they know what the Volunteers have been doing in communities. That resonates here. Mongolia has an incredible commitment to not allowing community spread of COVID-19. They understand why the Volunteers left. And they’re uniformly asking, “When are they coming back?”

Ukraine: The winter walk to school. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Michael Ketover | Country Director, Ukraine

FRIDAY THE 13TH of March, still only three cases confirmed in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government acts quickly: bans foreigners from entering, effective in 48 hours; 170 border checkpoints closed. We go to alert stage. Overnight a nationwide lockdown is imposed. We activate standfast. Saturday morning, airports close. Time to evacuate.

I was in Kryvyi Rih at a training with Volunteers and Ukrainian partners; took the 7-hour train back to Kyiv Saturday morning. Peace Corps in DC agrees on evacuation, finds a charter plane from Jordan, to arrive Monday. PC Ukraine, largest post globally, had 274 Volunteers serving; a large group completed service earlier that winter. Imagine doing this with the full 350 PCVs, I thought. We tell all Volunteers to get to Kyiv by Sunday night; they do. We get them to the airport — which is closed, skeleton staff. Still only seven cases in Ukraine. We wait. Flight delayed several times, then, about midnight, canceled. Hotels were closing. We found rooms in three; staff bought PCVs water and food, since restaurants were closing.

Tuesday’s charter: delayed then canceled. The company hadn’t arranged landing fee payment, secured a ground crew, etc. Wednesday: flight delayed several times, then canceled last minute. Despite support from the U.S. Embassy in Amman, the government of Jordan wouldn’t let the plane leave because of new COVID restrictions. Wednesday night I propose asking the U.S. military if we can fly Volunteers out on a military aircraft. And I talk to the CEO of a small startup airline in Ukraine interested in making its first flights to the States.

Thursday, 19 cases. We’re getting inquiries from congressional offices about concerned Volunteers’ parents: What’s going on? Thursday: delays, cancellation. Peace Corps HQ locates a different charter company from Spain. I insist on being put directly in touch with them. Thursday night 10:30 p.m., wheels up Madrid. We move PCVs in six different buses, with police and Regional Security Officer escort since it is now illegal to gather more than 10 people. At Kyiv airport, there’s a technical issue: They can’t issue or print boarding passes. So airport staff write them out by hand. Check-in took 10 hours. Friday morning, 6:20 a.m., plane departs. Kyiv to Madrid to Dulles to homes of record.

The real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter.

When I say we it’s the incredible PC local staff. Many had been through evacuation before, in 2014. I managed an evacuation in Papua New Guinea years ago but much less hectic and with only 22 PCVs. This time I was managing it from my Kyiv apartment — Friday I received notice that I had to self-quarantine because I had returned from Europe within the past two weeks. So I’m calling every Volunteer I could to say goodbye during that overnight check-in. During all this we’re posting on social media every day. This was time for gratitude: to counterparts and local staff, host families and government ministry partners, superstar volunteer wardens and our dear Volunteers. I encouraged the Volunteers to stay in touch with counterparts, work remotely if they could — on grant proposals, civic education with youth, English clubs on Zoom, anything; 100 evacuated PCVs have put in nearly 2,000 hours of virtual volunteering already.

Staff here have restarted programs before. They are working hard even without PCVs in country to maintain meaningful contact with counterparts. They know how to do it.

As for unfinished business, there’s goal one for Peace Corps — work Volunteers do in teaching, youth and organizational development. That’s important, but the real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter. When I talk to counterparts, local staff , and Volunteers, I emphasize this. Counterparts love it: Work, yes, but also inviting Volunteers to birthday celebrations, funerals, and weddings, berry picking in the forest — that makes this experience unique and awesome. The Third Goal, that’s unfinished: making America less insular — helping Americans appreciate the realities of life in different places. Those three goals, equally important, are the beauty of our wonderful organization.

Ghana: Gathering for a baby-naming ceremony. Photo by Meg Holladay

Gordon Brown | Country Director, GhanaIT HAD ALREADY BEEN A TOUGH YEAR for us in Ghana. In October, one of our Volunteers, Chidinma Ezeani, died after a tragic gas accident in her home. Thirty-nine Volunteers had to be relocated out of the northern part of the country because of security concerns across the border. Peace Corps Niger is closed because of security; Burkina Faso, too.

Then the virus: by March, regular emergency meetings at the embassy. Countries started closing, restricting airspace. It looked like Ghana was going to close — within the span of probably half a day. Sunday night, they said, Go in tomorrow and tell all 80 Volunteers to move. How fast can you do it? Now, our organizational culture in Peace Corps is not like the military: Here are your orders, execute. But in a moment like this, it has to be: Do this now — like now now.

My former boss used to say, “Being Peace Corps country director is the best job in foreign affairs.” I started as country director in Benin in 2015, then in Ghana in 2018. Along with the joy of the work also sometimes comes tragedy. So how do you be the best when times are the worst? Executing an evacuation takes massive logistical effort and focus. It was us all together — the Volunteers and the agency — that were able to make that happen. We had planes that were supposed to show up that didn’t. When we did get a plane — well, it had been a tough week for me personally, too. My wife had injured a muscle in her leg. So it’s 80 Volunteers, my wife in a wheelchair, our 3-year-old, our 7-year-old, all of our luggage — you can’t make up that level of difficulty. It was level 10.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

As hard as this has been, here’s something that I think has become clear to a lot of the Volunteers: You don’t stop being a Volunteer just because you’re no longer at your site in a country. We’ve got the technology now that allows many Volunteers to be connected all the time. But that doesn’t change the fact that you need to be able to communicate with people in front of you. You need to be able to read people’s emotions and speak with them in a way that is that being empathetic to what they’re going through.

We have to wrestle with what Peace Corps means in the modern world. How does it remain relevant? Ghana is the oldest Peace Corps operation in the world. It started in another era; 1961 was the year of Africa, when some 20 nations became independent. In 1960, the Prime Minister of England, Harold Macmillan gave a speech about “the wind of change” blowing through the continent.

In Ghana, one question is: How do we keep Peace Corps from seeming like a piece of old furniture? It has always been there. Kwame Nkrumah is always a big hero. John F. Kennedy is a big hero. America and Ghana have always had a close relationship. But how do we renew excitement among the government and people of Ghana — to understand that these Volunteers who are capable and tech-savvy, involved and committed, have something to offer? It’s a welcome challenge.

For the agency this is a massive undertaking in terms of charting the way forward: what the focus areas are going to be, what the footprint is going to be — what sectors, sizes, countries? All of that is going to have to be decided on an individual basis. As I like to tell Volunteers: Any victory lies in the organization of the non-obvious.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

Morocco: Girls’ hiking expedition. Photo by Gio Giraldo

Sue Dwyer | Country Director, Morocco

WHEN WE STARTED an in-service training there were maybe two cases in Morocco — a country of 35 million. But come Friday morning, March 13, I don’t like where this is going. They shut down flights to Italy, are talking about shutting down flights to France — our primary means of getting out. We cancel the last few days of training. We send Volunteers back to their sites, put them on standfast.

Saturday morning, I call the Deputy Chief of Mission at the embassy and tell him I think I have to get Volunteers out; if we have to med-evac someone, we’re in trouble. We’ve got 183 Volunteers and Morocco is the size of California. For some Volunteers it takes two days to get back to site; they get a day to pack, say goodbye. In Rabat I figure we’ll have three days for a program to wrap things up. The embassy says you’ve got until next Saturday … then Thursday … then Wednesday. OK, here we go. The Moroccan government keeps moving the time when we can fly. I realize, as this is happening, that I still have some muscles working from my humanitarian aid days; I evacuated NGOs out of Liberia in 1999 during the civil war.

A lot of Volunteers email me saying, “Please don’t send us home, we want to be here in solidarity with the Moroccans.” But they come. Some have problems getting back to Rabat — harassment on buses, people saying foreigners brought in COVID. So our Moroccan staff charter buses and send them out to consolidation points.

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh.

At the airport we have a charter flight with maybe 225 seats for Volunteers only. They start calling: “My grandmother and my mother are here — and the airport’s closed.” So we say yes. Then: My parents, my aunt , my brother. So we have to finish what we started. Thursday at 2 a.m., the plane takes off. Second-year Volunteers knew they were being COS’d. First-year Volunteers were told they were on administrative hold. While they were flying that changed. They got off the plane, they got a different message. That was soul-crushing.

Peace Corps Morocco is one of the oldest programs, and currently the only one in the Arab world. We’re the largest youth development program; it’s our sole area of focus. The evacuation was a huge earthquake with all the aftershocks. And it’s not just for Volunteers. We’ve got host families calling and saying, “I can’t reach my volunteer daughter, son” — because their number changed. “When we see what’s happening in the United States, we’re really worried. Are they OK?”

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh. If we were to do training in a completely different way, what would that look like? So this is an important time for innovation and rethinking our models

.

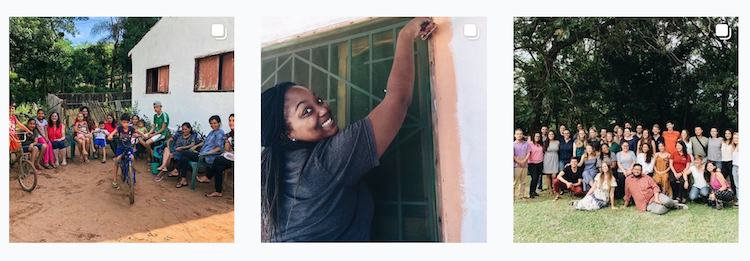

Paraguay: Scenes from an Instagram feed before evacuation

Howard Lyon | Country Director, Paraguay

WE KNEW THE VIRUS was on its way, burning across the world. It was going to hit Paraguay sooner or later. Infections had begun in Brazil. At the time we thought maybe we could ride out the storm. But the world was getting stormier. Then with the infections in the United States, we began getting inquiries from parents: “Where’s my daughter?” “What’s your plan?” I had traveled to the region called the Chaco — very isolated and hot, and there was the theory that the virus doesn’t like heat. That was my last trip to the field.

By March 15 it was very serious. A strange morning, overcast, leaves beginning to fall; autumn was just beginning. Walking to our office I was the only person on the street — a major thoroughfare in Asunción. People were beginning to stay at home; the government was making noises about curfews. We started preparing for lockdown. This happens to be my second evacuation in two years; in 2018 we evacuated Nicaragua — though under very different circumstances. But it’s heartbreaking to take Volunteers from their communities.

Sunday night we got the call. We had a week to get 180 Volunteers out. Paraguay is an inland island, surrounded by Brazil, Argentina, and Bolivia. Politically it was isolated for years. You fly to North America through São Paulo, Buenos Aires, or Santiago, and then another connection. We got word that Panama, a central hub to get people to the U.S., was going to close. By Wednesday word was the airport in Asunción might close. We even had a group on a bus to the airport when our travel agency canceled our tickets. So we brought people back to their hotel. Saturday, we got a chartered flight, our last large group. Lockdown began the night before; we weren’t even allowed to leave our homes to say goodbye to them. So it’s all WhatsApp, and we’re calling, we’re saying goodbye in other ways.

THREE MONTHS LATER, Latin America is being harder hit. Volunteers I speak to express gratitude to the country, sadness for leaving their communities here, but also gratitude for being close to their families in the U.S. during this time. In Paraguay, we were on strict lockdown the first month, and that helped. In Peru and Ecuador, it’s a terrible situation. Brazil is horrific. Here the population is about 7 million. We’re around 1,300 cases now; there have been 12 fatalities.

Our staff have been talking to community members and counterparts. They want everybody back. But it’s going to be a different world. In Paraguay, kissing and hugging are a big part of the culture; so is sharing food, or drinking tereré out of the same gourd or straw. That will change. If the opportunity presents itself to return Volunteers, they will be well received by their communities. But we’re going to have to think about how you go in as the foreigner who has been in a country with such high infection rates.

Another crucial factor: New and returning Volunteers alike have not only lived through an extraordinary world health catastrophe, but the recent murders of Black Americans, which are a consequence of centuries of racism, have brought another time of protest and a time of reckoning. All of us as individuals and as organizations have to look within ourselves and truly recognize that this situation — the mistreatment of people because of race — is the heritage of our country. We have to deal with it. It doesn’t mean everybody’s bad, doesn’t mean everybody’s good. It just means we’ve got to live together.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class.

When the Black Lives Matter movement began a few years ago, there were repercussions in the Peace Corps. Some wanted the agency to answer hard questions. This is now even stronger and more tragic. The economy and unemployment, the illness and who it affects most, and the reckoning with justice: It’s an extraordinary time. So our staff need to be compassionate and understanding.

I haven’t been to every country in the world, but I’ve seen a bunch. And I don’t know of any non-racist country, especially in this part of the world. Africa was colonized by Europeans who, to do what they did, dehumanized native populations. That curse has been with us ever since. In this part of the world, when we talk of Europeans — the Spanish and the Portuguese — this conquest was very violent. These nations were born in violence, but they’re trying to reckon with it.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class. Every one of us is facing uncertainties — and we’re social distancing, losing human contact. I hope compassion is what we learn out of all this. It’s not just, OK, lights are on again.

As I said to the last group flying out, when I called and they put me on speakerphone: We truly love you guys. We love you Volunteers.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thank you for reading: We try to bring you stories that matter to our community. We welcome any support you can give for the work we’re doing.

-

Joanne Roll

Joanne Roll

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate... see more

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate what a herculean effort was made by PC staff to evacuate all Volunteers, safely.3 years ago -

Michael Burza I sincerely hope as many PCVs can return to their sites as possible.3 years ago

-

Steven Saum posted an articleThe first Peace Corps Volunteer in a village in southern Ghana chronicles who and what she left. see more

Ghana | Meg Holladay

Home: Amherst, Massachusets

I was serving as a Peace Corps Health Extension Volunteer in southern Ghana, in a farming community of about 1,200 people. When we were evacuated, I had been in my community for a year and had one more year to go. I was the first Peace Corps Volunteer there. I felt like I was just starting to hit my stride, to identify the projects that would be truly helpful and the people who were the most committed to working together for the long term. I was working with community members on a health education class, household latrines, and a school library. We were starting to plan a snail farming project and a rainwater harvesting initiative.

What did I leave behind?

I left behind giant papayas and a little fruit called “alakye,” with bright red flesh that tasted like a sour plum and a peel that oozed rubbery latex sap. I left behind silvery dried fish, red palm nuts, and sweaty heat. I left behind a garden I’d just planted — cucumber, watermelons, basil, peanuts — and the concrete bedroom I’d finally painted green. I left behind delightful TV commercials with identically dressed dancers, and an ongoing “Coke famine” in which the only kind of Coca-Cola available anywhere was Coke Zero. But mostly, I left behind people — hundreds of people I saw almost every day. Friends I planted rice with and chatted with in the hot afternoons, friends I washed clothes with and laughed with, friends who asked me uncomfortable questions about America. Old people, babies, taxi drivers, traditional midwives, rice vendors, church pastors. My twelve-year-old neighbor who passed by my house every morning on her way to school, her books stacked neatly on her head.

I had to leave a lot of things unfinished.

Every Sunday evening, I led a community health education class. The class was open to anyone who wanted to come, and every week, the people decided together what they wanted to learn about the following week. I would research the topic and plan a lesson with help from Ghanaian friends, and one of them would interpret for me during the meeting. People were so curious about health and the human body, but information wasn’t always available; even for those who could read English (the language of education in Ghana), my community didn’t have access to phone data, much less health books or a library.

We studied malaria, breastfeeding, hernias, the female and male reproductive systems. One person asked “Why do women sometimes die during childbirth?” That led us into a whole series of classes about pregnancy, labor, and birth. People asked good questions. “When is the fertile time in a woman’s menstrual cycle?” “Is it dangerous if a pregnant woman works too hard on the farm?” “I once saw a baby boy who was born without testicles in his scrotum. What causes that?” Every week, I was impressed with how much people remembered from the week before.

People were so curious about health and the human body, but information wasn’t always available; even for those who could read English (the language of education in Ghana), my community didn’t have access to phone data, much less health books or a library.

We played games, did skits, invented little cheers. I made giant drawings and blew up balloons to represent internal organs. The class even developed their own greeting: Every week, when people arrived, they would call out “Apɔmuden” (“Health”), and those who were already there would respond “ɛhu hia paa!” (“It’s very important!”). The last class I led, on March 15, was about natural family planning, and the topic the people requested for the following week was sexually transmitted infections. I had expected that I’d have many more months to brainstorm with my counterparts on how the community could continue learning about health after my service was over, but unfortunately we didn’t have time to do that before the evacuation.

We were also working on lots of other projects that I wasn’t prepared to leave behind. I had helped coordinate my community’s involvement in a household pit latrine project, and we’d finally finished 87 latrines a few days before I left. But because of high groundwater, about 50 households hadn’t qualified to build them. I had been doing research on different latrine designs, hoping to help those people find an alternative type of latrine that would work where they lived.

I was working with a teacher in a neighboring community who was interested in starting a school library, which would have been the first in the area. Together we identified possible sources for books in English and Twi (the local language), and ways to raise money in the community, but that was as far as we’d gotten when I was evacuated. The teacher plans to continue on his own once school reopens after the pandemic.

Neighbors: Meg Holladay with Efia and son Odoom. Photos courtesy Meg Holladay

I was also planning to work with one of my neighbors on snail farming. Giant snails are eaten as a delicacy in southern Ghana, and a Peace Corps friend had taught me a simple way to make a snail enclosure out of used tires. My neighbor, already a beekeeper, was excited to try this out and teach it to others, giving households a nutritious protein source, and extra income from selling the snails. We were going to start in May, once the rainy season arrived.

And I was working on a drinking water problem. Many people in my community drank water from a local river, because even though we had wells and pumps, the groundwater that came from them was salty — our geological bad luck. Most people felt the river water was fine to drink; they said it tasted fresh and didn’t make them sick. But just a few weeks before I left, I had an exciting conversation with one of my neighbors. My Twi was just starting to be good enough that he and I could finally communicate well, in a mixture of Twi and English. It was the height of dry season, and we were standing next to the river, which was down to a trickle. My neighbor told me he felt the river water was dangerous to drink, because of contamination from the agrochemicals that farmers used upstream. He told me he wanted change, he wanted everyone to have better water, but he didn’t know what could be done. I suggested that we could help the community set up rainwater collection and storage systems, and he loved the idea. We were just about to start planning how to do this when I had to leave.

Peace Corps work is so powerful because it’s work we do together with our communities, based on their priorities. It’s work that can become sustainable as we share knowledge and learn together.

I think Peace Corps work is so powerful because it’s work we do together with our communities, based on their priorities. It’s work that can become sustainable as we share knowledge and learn together. And it’s work that includes living our daily lives with our host country friends and neighbors. I hope that after the pandemic, I’ll be able to continue this work with my community in Ghana — or that if I can’t, a future Peace Corps Volunteer will.

Two days before I left my community, the power went out for the evening. I joined my neighbors outside their house, where the kids and I lay on a comfortable mat, looking up at the stars and enjoying the cool breeze, and their parents relaxed on a wooden bench. I asked them if they knew any folk tales. My friends and their children started telling stories one after another — funny stories, stories I couldn’t understand at all unless I made someone repeat them word by word, half in English. Soon I gave up on trying to understand and just listened to my friends laugh together. But I think if I had been able to stay another year, I might have understood enough to laugh with them.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thanks for reading. And here’s how you can support the work we’re doing to help evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers.

-

Jonathan Pearson posted an articleDo NPCA advocates make a difference? You need to read about these two first timers to Capitol Hill. see more

Many among the estimated 230 National Peace Corps Association advocates who participated in our Peace Corps 55th Anniversary advocacy day had no previous experience in the world of Capitol Hill citizen-lobbying. Among them were our October Advocates of the Month, the Ashland, Oregon husband and wife team of Asifa Kanji and David Drury.

For David and Asifa, their Peace Corps experiences were recent and extensive, serving first as 27-month Volunteers in Mali from 2011 - 12 and later signing on as Peace Corps Response Volunteers in both Ghana and South Africa.

Capitol Hill? That was another story.

The couple didn't know exactly what to expect when they signed up to take part. "As first-timers, Asifa and I were a little nervous about it all", said David. "How are you supposed to act around a Senator or Congressperson? What do you say? We didn't want to be an embarrassment to Peace Corps."

That, they were not! And, as Asifa noted, "Whoever would have thought (advocating on the Hill) would be the highlight of my Peace Corps Connect experience."

David and Asifa studied the NPCA briefing papers the night before, and gathered at a church on the morning of advocacy day, joining four other Oregonians who also had little or no advocacy experience. With this in mind, NPCA bolstered the group by connecting them with Pat Wand, a former NPCA Board member and long-time Capitol Hill advocate who had previously lived in Oregon. The first stop was a constituent coffee where the group had a few minutes meeting junior Senator Jeff Merkley, followed by additional time with his staff to make the case for increased Peace Corps funding and better health care support for Volunteers and RPCVs with service-related illnesses or injuries.

Wand got the group started with both of the group's Senate meetings. But then it was time for Team Oregon to split up and meet with their respective members of the House of Representatives. "Oh my, we are on our own!" thought Asifa. "Suddenly, it was my turn to speak to my Republican representative."

In this case, the meeting (pictured above) was with Congressman Greg Walden, a key member of the House Republican leadership. Asifa shared her story of being an immigrant to this country, and how her decision to become a U.S. citizen was very much due to her desire to serve in the Peace Corps. "I have to tell you, I have never been so proud to say I was an American as when I was in the Peace Corps."

Upon sharing she was originally from Tanzania, Congressman Walden noted he had recently visited that country on a congressional delegation (CODEL) with RPCV Congressman and Peace Corps champion Sam Farr. He pulled out his i-phone, shared photos and talked about his CODEL trip.

With a strong connection made, David and Asifa got to the business at hand. As Asifa recalls, "After that it wasn't hard to look him in the eye and with a big smile ask him to co-sponsor H.R. 6037 (Peace Corps health legislation). My husband, who knew that Rep. Walden had worked hard to improve the medical services military vets get, was quick to add that PCVs have served their country too and deserve better care for medical conditions related to their service. The congressman was on board. Wow."

Congressman Walden became one of the first co-sponsors of the legislation. and there is no doubt it was due to the efforts of Asifa and David! The meeting had more than a passing impact, as RPCV Congressman John Garamendi shared the story of being approached later that day on the House floor by Congressman Walden, who wanted to tell him about the meeting with his RPCV constituents.

David was generous in his praise of the NPCA for a successful first-time advocacy experience. "We couldn't have done it without the fantastic support provided by the NPCA staff and advocacy volunteers...The NPCA staff did all the heavy lifting, setting up appointments, providing briefing sheets, and heading up each state delegation with an experienced person who showed us how it should be done. They worked their tushes off* to make us look good. And once you've done it, you see how satisfying and fun advocacy can be."

We are very proud of our advocates of the month for their highly significant and successful participation on Capitol Hill.

NPCA can continue congressional outreach only with your support. Donate now to the Community Fund to advocate for a bigger, better Peace Corps.