Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleA diplomat committed to peace and prosperity in the Caribbean see more

He began his career as a teacher with the Peace Corps | 1949–2021

He was a diplomat who devoted decades to advancing peace, prosperity, equality, and democracy in the Caribbean. Peace Corps service set him on that path. Equipped with a bachelor’s from Emory University, he headed to Liberia as a Volunteer (1971–73) and taught general science, biology, math, and chemistry. He admired the commitment of U.S. Embassy staff he met.

He completed graduate degrees in African studies and education, then embarked on a career that took him to the Dominican Republic, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Ecuador before he was appointed ambassador to Honduras (2002–05) by President George W. Bush. He served as president and CEO of the Inter-American Foundation, focused on grassroots development in Latin America and the Caribbean, expanding support for underserved groups, including African descendants.

President Barack Obama tapped Palmer to serve as U.S. Ambassador to Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean (2012–16); Palmer concurrently served as ambassador to Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. He understood the value of building relationships in person.

A moment with the press: Larry Palmer after speaking with the president of Honduras in 2002. Photo by Esteban Felix / AP

A story he shared, from a conversation with Alejandro Toledo, who, Palmer said, “always talks about his experience as a young student when a Peace Corps Volunteer identified him as a potential excellent student and leader and pushed him and gave him the courage that he needed to move on, further his education … And of course he ended up as president of Peru.” Larry Palmer died in April at age 71.

—Steven Boyd Saum

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleThe globe in 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers see more

In 1961, nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers.

THE GLOBE IN 1961, the year nine countries welcomed the first Peace Corps Volunteers — and the year after 17 nations in Africa gained independence. For the first Peace Corps programs, demand is strongest for teachers and agricultural workers. Volunteers are urged to embark on their journey in the spirit of learning rather than teaching. To lay the groundwork, Sargent Shriver, the first Director of the Peace Corps, undertakes a round-the-world trip to eight nations from April to May.

Photos by Brett Simison. Words by Jake Arce and Steven Boyd Saum

St. Lucia, an island in the Eastern Caribbean, is the third program to host Volunteers: 16 train at Iowa State University and arrive in September. The island will gain independence from the British Commonwealth in 1979.

Volunteers arrive in Colombia on September 8: All are men, ages 19 to 31. The endeavor involves a partnership with CARE. Some work in community development with the Federation of Coffee Growers, some in the Cauca River Valley in the southwest.

In Chile, 42 Volunteers train to provide assistance in community development and education as part of the Chilean Institute of Rural Education, a nonsectarian private organization. They're in service by October, working with Chilean educators in developing programs in hygiene, recreation, and farming.

Shriver tours Latin America in October. Four countries sign agreements to host Volunteers in 1962. In Brazil Volunteers will work in rural education, sanitation, and health, and in poor urban areas in the northeast. In Peru they will work in indigenous highlands and impoverished urban areas. In Venezuela, work will include teaching at a university and as county agricultural agents. Bolivia asks for engineers, nurses, dental hygienists, and food educators.

Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah speaks at the U.N. and meets JFK in March. Shriver visits him in April — not long after the Ghanaian Times denounces the nascent Peace Corps as an “agency of neo-colonialism.” But after hearing Shriver, Nkrumah says, “The Peace Corps sounds good. We are ready to try it and will invite a small number of volunteers ... Can you get them here by August?” They arrive August 30, the first Volunteers in service.

President of the Philippines Carlos B. Garcia has pursued a Filipino First policy, noting, “Politically we became independent since 1946, but economically we are still semi-colonial.” The final stop on Shriver's spring round-the-world tour, the country welcomes 128 Volunteers in October to supplement teaching in rural areas, focusing on English and science.

Nigeria gained independence from Britain on October 1, 1960. Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa asks Shriver to send teachers; the country has only 14,000 classroom slots for more than 2 million school-age children. First Volunteers arrive by end of September.

India, a country of half a billion people, is led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru — de facto leader of the nonaligned nations, those allied with neither the United States nor USSR. When Shriver visits in spring 1961, Nehru is skeptical but allows, “In matters of the spirit, I am sure young Americans would learn a good deal in this country and it could be an important experience for them.” He agrees to host a small number of Volunteers in Punjab. A cohort of 26 arrives December 20. After India agrees to host Volunteers, so do Pakistan, Thailand, and Malaya.

Pakistan’s President Mohammad Ayub Khan came to power in a coup in 1958 and was elected by a referendum in 1960. Addressing the U.S. Congress in July 1961, he calls for more financial assistance. The first group of Volunteers arrives in West Pakistan in the fall to serve are junior instructors at colleges, as well as teachers of farming methods and staff at hospitals.

First Volunteers arrive in Tanganyika on September 30: civil engineers, geologists, and surveyors, there to build roads and create geological maps. The country is a U.N. trusteeship that achieves full independence in December. Also note: in October, 26 Volunteers begin training for service in Sierra Leone in 1962.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleAn invitation to listen, learn — and roll up our sleeves see more

An invitation to listen, learn — and roll up our sleeves.

By Steven Boyd Saum

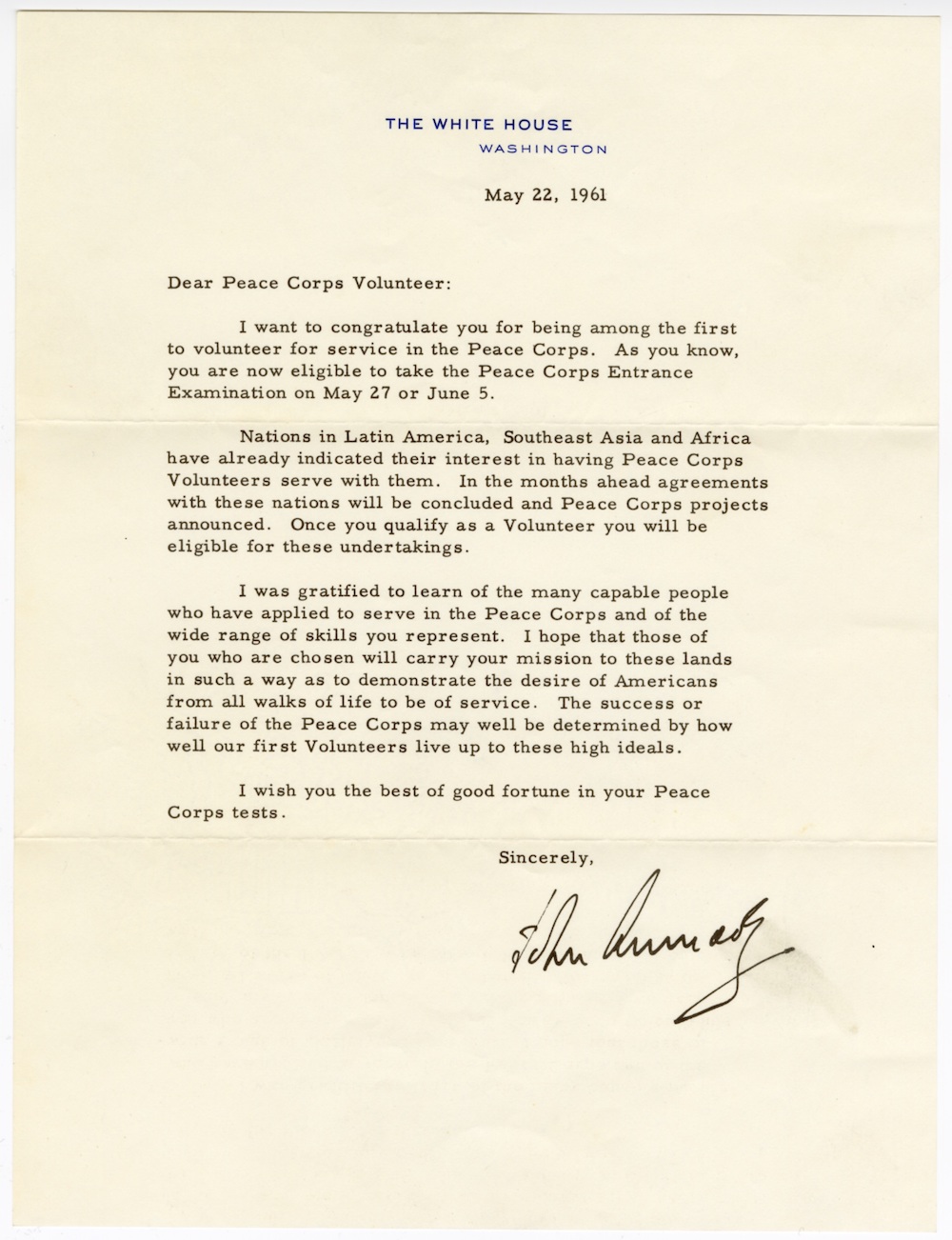

Let’s start with a story about an invitation. There’s that historic letter from JFK below, sent to the first would-be Volunteers. And let me tell you about Laurel Hunt, a recent engineering grad from University of Minnesota, and the years of Peace Corps service she has yet to undertake in Peru, working with a community on health and sanitation. Return to March 2020: “Friday the 13th was my last day at work,” Hunt writes. “As I packed up my desk that afternoon, I got a phone call from Washington, D.C. A frazzled-sounding Peace Corps employee told me that my Peru 35 group would be delayed at least 30 days.”

COVID-19 was burning its way across the globe, countries shuttering airports and closing borders. Two days later, Peace Corps announced a global evacuation of all Volunteers.

Peace Corps was something Laurel Hunt had her heart set on since junior high. While earning her engineering degree, she co-founded and served as president of Out in STEM. “As a queer woman in engineering, I’m used to feeling out of place,” she says. Peace Corps would no doubt bring more of that sense of displacement, in ways humbling and unexpected — and, so the story goes, lessons in patience, flexibility, resilience.

“I don’t know what my future holds, and the uncertainty is tough,” Hunt wrote a year ago. “For right now, all I can do now is wait, support my community, and wash my hands. I’m incredibly fortunate to have a safe place to stay and enough savings to make it through a few months in limbo.”

On her blog she wrote with admiration about returned Volunteers who, as the global evacuation was taking place, rallied to help the evacuees. There was a Facebook group focused on providing that support; within days, its membership swelled to 6,000 members, and then 14,000. Hunt pitched in as an administrator for the group.

She hoped, as so many did, that the pandemic might be tamed — and that Volunteers would return to their sites later in the year. By summer it was clear that wouldn’t happen. Hunt took a job at a seafood processor in Alaska for a few months. She returned to Minnesota. The firm where she had been working offered her a job again, while she waited to hear when she might begin Peace Corps service.

“The uncertainty is tough,” wrote would-be Volunteer Laurel Hunt. So she established a group to support others in the same boat: Peace Corps Invitees in Limbo.

Many hundreds of others were in the same boat, waiting. So Hunt formed a Facebook group to give them a place to share updates (what’s the latest on departure for your country?) and to offer advice and support and a shared sense of what it was to be living with this uncertainty while other forces in life exerted their gravitational pull. Hunt christened the group Peace Corps Invitees in Limbo.

When the first Peace Corps Volunteers received their letters of invitation from President Kennedy 60 years ago, they were embarking on something uncertain and new. When Volunteers arrive once more in countries around the world, the communities and individuals who serve there will begin a journey very different from what has come before. I have heard from one of my former students — Olena Halapchuk-Tarnavska, who is now on the faculty at Lesya Ukrainka Volyn National University in western Ukraine and who has been training incoming groups of Volunteers for years — that they are eager for Volunteers to return. Those sentiments have been heard from every country where Volunteers were serving. But how things will be different remains to be seen.

When the first Peace Corps Volunteers received their letters of invitation from President Kennedy 60 years ago, they were embarking on something uncertain and new. When Volunteers arrive once more in countries around the world, the communities and individuals who serve there will begin a journey very different from what has come before.

As we mark the 60th anniversary of Peace Corps beginnings, in the spring 2021 edition of WorldView we also lean hard on what Peace Corps might be — and what place it has in a changed world. And not only Peace Corps, because this audacious endeavor — independent from the exponentially larger USAID and State Department, thanks to the vision and efforts of the early architects of the agency — does not exist in a vacuum. Which brings us to the words on our cover: The Time Is Now! For what? To commit as never before to a sense of service with a sense of solidarity, building up communities across the United States and around the world, fostering the personal connections that deepen our awareness and understanding — of shared humanity, of what equity and justice mean, and, for better or for worse, a common fate on this planet.

The thing about service and solidarity is that these are not a one-and-done commitment, boxes to be checked. For this work, there’s a standing invitation.

WATCH: Laurel Hunt on why she wants to serve in the Peace Corps.

Letter image courtesy Maureen Carroll Collection, Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Archives and Special Collections

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView and director of strategic communications for National Peace Corps Association. He served as a Volunteer in Ukraine 1994–96.Write him.

This essay appears in the spring 2021 edition of WorldView magazine. Sign up for a print subscription by joining National Peace Corps Association. You can also download the WorldView App for free here: worldviewmagazine.org

-

Steven Saum posted an articleWe help out from the confines of our house and maintain a strong link to both the people and place see more

Peru | Aidan Fife

Home: Lancaster, Pennsylvania

When Aidan Fife arrived in the Ancash region in December 2019, he was the third youth development Volunteer to serve as part of a six-year project, stretching over the course of three cohorts. “Kind of a new thing for Peace Corps,” he says.

Though Peace Corps is not new in Peru. The program was established in 1962 and ran until 1974, when it was suspended because of political instability. Volunteers have been back since 2002.

Fife’s aunt served in Paraguay in the 1980s. “She’s my number one inspiration,” he says. She lauded the three-volunteer sequence structure; it showed a more sophisticated Peace Corps engaged in development that would be sustainable.

Mount Huascarán in the Ancash Region of Peru. Photo courtesy Wikimedia

Fife was working in a town within view of twin-peaked Mount Huascarán in the western Andes. He studied Spanish and environmental science in college, and in Peru he began learning Quechua. You could get by without it, he says, but he wanted to integrate himself in the community, working with a school and a health center. He was teaching life skills and career orientation and sex education.

First, he brought out some art supplies for the four children in his host family — aged 18 months to 14 years. They were delighted. “Then I told them I’m leaving. That was hard.”

He had less than eight hours to pack, say hurried goodbyes, get to the regional capital. First, he brought out some art supplies for the four children in his host family — aged 18 months to 14 years. They were delighted. “Then I told them I’m leaving. That was hard.”

That night Peru closed its borders. Nearly all flights were canceled. That made evacuation tough. But Volunteers did get out. Weeks later, there were some 2,300 Americans who were still trying to leave.

Fife is back at his parents’ home. When we spoke, he was in self-quarantine before worrying about what’s next. Evenings, he was on video chats with his host family in Peru. “That’s been nice,” he says, “because then they can meet my family here.”

—Steven Boyd Saum

Peru | Madeline and Clint Kellner

Home: Novato, California

We were eight weeks into our second Peace Corps service as Response Volunteers in the Peruvian Amazon when we were evacuated. We served previously as Volunteers in Guatemala’s western highlands, 2016–18. In 2020, we were assigned to the nonprofit Minga Peru, dedicated to economic and social empowerment of indigenous women and the well-being of families and communities.Minga Peru brings vital health information and other important messages to more than 100,000 indigenous residents living in isolated communities along the Amazon through their radio program, “Bienvenida Salud.” To reinforce those messages, they run a project to train promotoras, local lay women health promoters. To share the nonprofit’s success with interested outsiders and to market locally-made artisanal products, they started an educative tourism program called Minga Tour.

Based in Iquitos, our charge was to work shoulder to shoulder with staff to strengthen and advance these programs. Madeline was focused on strengthening community radio and promotora leadership; Clint’s attention was directed at development and marketing of educational tourism. We were inspired by the successful inroads the nonprofit had already made and by the women leaders we met.

Promotoras — health promoters with Minga Peru. Photo courtesy Madeline and Clint Kellner

What now? Back in Marin County, we followed the 14-day self-quarantine and then began shelter-in-place. There was no homecoming for us. We can feel the disappointment others are experiencing, with canceled weddings, stalled charitable fundraisers and memorial services for loved ones, postponed surgeries, and delayed trips. Also palpable is the fear, anxiety, and panic in the grocery store, on the streets and trails, and in the media. None of us has ever experienced a situation like this — with so little certainty, no definable end in sight, no assurances that this cannot happen again.

What has brought us a renewed perspective in the midst of so much change? Since our return, we learned that Minga Peru now faces new critical challenges with funding shortfalls and a higher demand for services. The Peruvian Amazon is home to more than 1,000 rural communities, most in isolated riverine areas, with poor access to essential services. COVID-19 dramatically impacts this region already besieged by dengue fever, shortages of hospitals and medical professionals, and high rates of poverty and food insecurity. Tourism has stopped — cutting off an important source of revenue.

What we cannot do in person in the Amazon, we do remotely in the United States.

What we cannot do in person in the Amazon, we do remotely in the United States. We are contacting past and potential donors to help fund Minga’s emergency response plan, beefing up the radio program’s COVID-19 messages and advice, and providing essentials like soap, cleaning supplies, and vegetable plants for gardens.

What helps: keeping the faces of the indigenous women and their families whom we met in our sights. That gives us the motivation we need. It also gives us focus outside ourselves. We don’t know what’s next and if we will be able to return to the Peruvian Amazon. In the meantime, we help out from the confines of our house and maintain a strong link to both the people and place.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thanks for reading. And here’s how you can support the work we’re doing to help evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers.