Activity

-

Tiffany James posted an articleThe highest award given to foreign citizens was presented to Country Director Kim Mansaray see more

The highest award given to foreign citizens was presented to Country Director Kim Mansaray.

By NPCA Staff

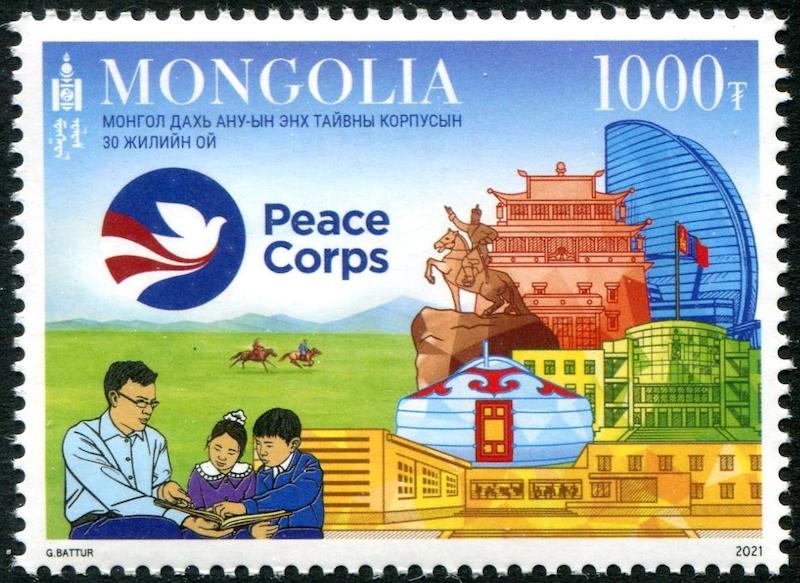

Photos courtesy the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia

For the 30th anniversary of the Peace Corps in Mongolia, last summer Country Director Kim Mansaray — who served as a Volunteer herself in Sierra Leone 1983–85 — was presented with the highest award given to foreign citizens: the Order of the Polar Star. In a ceremony with Deputy Foreign Minister Munkhjin Batsumber of Mongolia, the award was bestowed on Peace Corps Mongolia and its leadership for peace-building efforts in the country.

Nearly 1,500 Volunteers have served in Mongolia since 1991, contributing their skills to the social development and well-being of its citizens.

Presentation of the Polar Star: Deputy Foreign Minister Munkhjin Batsumber of Mongolia, right, with Peace Corps Mongolia Country Director Kim Mansaray

Three Decades of Service

December 2021 saw more special recognition for Peace Corps Mongolia: the release of a commemorative stamp to celebrate three decades since the first Volunteers arrived. The stamp features the Peace Corps logo; a Volunteer teaching young children; and Mongolian landmarks.

-

Ana Victoria Cruz posted an articleA Volunteer on his first experience organizing meetings with Congress to advocate for Peace Corps see more

A Volunteer evacuated from Mongolia on work to help members of Congress understand the value of Peace Corps service — and what they can do to help

By Daniel Lang

The summer of 2019 I was training to serve as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Mongolia. More politically involved peers raised concerns that we should not take for granted that legislators would continue to fund the Peace Corps; more than 100 members of the House voted to defund it. That fall I swore in as a Volunteer and a close friend, Austin Frenes, began service in China. We both received assignments as university English instructors.

In January 2020, Austin learned his cohort would be China’s last; the program would, in Peace Corps terms, graduate. Mongolia began to restrict travel amid a preemptive quarantine. Peace Corps China consolidated in Thailand — then ended. In February, Peace Corps Mongolia evacuated; we were put on administrative hold. A week later, home in Nevada, I got word that our service was closing. I’m waiting to hear when we might reinstate.

I wasn’t looking for a leadership role in organizing meetings with members of Congress. I had no experience as a citizen lobbyist. But in August I saw a call to action email from National Peace Corps Association asking me to do exactly that, as part of a “virtual district office initiative.” I attended a webinar and learned NPCA had no documented meetings of returned Volunteers with Nevada’s congresspeople. I knew our legislators could do more to support Peace Corps.

The possibility of making important contributions like this are why, we said, it was important for Peace Corps to both become better and to redeploy.

NPCA’s Advocacy Director Jonathan Pearson helped me to decide which lawmakers to meet with. He put me in touch with other Nevada RPCVs whose service spanned continents and decades. They were strangers to me personally, but we had that common bond as Volunteers. They also echoed advice I had heard in training: We might not know the greatest impact of our service for years to come.

Earlier in the summer I had shared a story of my Peace Corps service with a high school classmate. Through her, we were able to arrange a Zoom call with the staff of my congressman, Steven Horsford (D-NV) in September. On the call were fellow Volunteers Alexis Zickafoose (Georgia, 2018-20), Alan Klawitter (Liberia, 1975-77), Taj Ainlay (Malaysia, 1973-75) and Kathleen DeVleming (Ethiopia, 1972-74). Alexis was just finishing her second year of service when she was evacuated. Alan and Taj shared stories of their service and the impacts of Peace Corps over the years — reasons why we were asking our representative to support H.R. 3456, the Peace Corps Reauthorization Act introduced by RPCV Rep. John Garamendi (D-CA), and H.R. 6833, the Utilizing and Supporting Evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers Act introduced by Rep. Dean Phillips (D-MN).

RPCVs in the Show Me State: A district meeting with staff from U.S. Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO) included Kirsty Morgan (Kazakhstan 1998–2000), Erin Robinson (South Africa 2005–07), Don Spiers (Venezuela 1973–75), Joseph O’Sullivan (Brazil 1973–75), Amy Morros (Mali 1996–98), and Mia Richardson (North Macedonia 2018–20), founder of RPCVs Serving at Home. Photo by Amy Morros

Kathleen raised points about the skill sets of many Volunteers, and the importance of legislation aimed at putting RPCVs to work to help combat the pandemic here at home. She spoke about the work that her husband, John DeVleming, had done to eradicate smallpox in Ethiopia while serving as a Volunteer and working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The possibility of making important contributions like this are why, we said, it was important for Peace Corps to both become better and to redeploy.

I realized a few things from this experience. This work is all in our Third Goal — helping Americans, including our representatives and senators in Congress, better understand the world. It’s also part of showing openness, adaptability, and flexibility. And serving as a citizen lobbyist at home is much like engaging in citizen diplomacy abroad.

Ultimately, all U.S. citizens can contact our leaders — or, should I say, our public servants. I know we’re all called to act in different hours. I felt this as my hour. I hope you consider this, too. Let’s help make sure that Peace Corps endures as something even better than it has been.

As of press time, RPCV advocates have organized 30 virtual district office meetings across 16 states, with dozens of additional meetings being sought. Make plans to participate in our next round of district meetings, coming in March 2021 during our annual National Days of Action.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Fall 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleFive country directors tell the stories of Peace Corps evacuation. see more

When times are good, being a country director for Peace Corps may be the best job in foreign affairs. This has not been such a time.

As told to Steven Boyd Saum

Photo: Vyshyvanka Day, when schoolchildren don the traditional Ukrainian shirt — and here, pose as one. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Kim Mansaray | Country Director, Mongolia

JANUARY AND NEWS OF THE VIRUS came out in China. Mongolia says we’re not sending kids back to school. Our winter break became endless winter break. Then the virus exploded in China, and Mongolia went on hardcore lockdown — borders and flights.

From time to time in Mongolia, there’s an outbreak of something, then a quarantine — fairly routine. That was on our minds: Watch how this plays out. The clincher was when flights from Seoul were canceled. I talked to the embassy and said, If people need to be medically evacuated, we’re not gonna be able to get them out.

The farthest part of the country is normally a 40-hour bus ride. It took five days with help from embassy cars to caravan all Volunteers back in. And of course, because it’s Mongolia, there was a blizzard.

Volunteers just a few months in were put on administrative hold. Then, in mid-March, Washington moved everybody to Close of Service. My Volunteers were giving me grief. I said, I get your frustration and your anger. But this is unchartered territory for Peace Corps.

Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the volunteers back as soon as possible.”

Mongolia on horseback. Photo by Antonio Mercatante

Fast forward to June: Our staff in Mongolia have been out and about and in the countryside, visiting potential sites, picking up luggage that Volunteers left behind. And making honest assessments: Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the Volunteers back as soon as possible.” There’s a real connection. Volunteers are staying in touch with communities. Mongolia is incredibly wired; they use Facebook for everything.

Here, they see what’s happening in the U.S. Three, four days a week, people come in my office and ask: “What is going on?” Diplomatically I say, “Our democracy is right out there for you to see. It’s messy and it’s ugly, and it’s been tough.” But they know what the Volunteers have been doing in communities. That resonates here. Mongolia has an incredible commitment to not allowing community spread of COVID-19. They understand why the Volunteers left. And they’re uniformly asking, “When are they coming back?”

Ukraine: The winter walk to school. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Michael Ketover | Country Director, Ukraine

FRIDAY THE 13TH of March, still only three cases confirmed in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government acts quickly: bans foreigners from entering, effective in 48 hours; 170 border checkpoints closed. We go to alert stage. Overnight a nationwide lockdown is imposed. We activate standfast. Saturday morning, airports close. Time to evacuate.

I was in Kryvyi Rih at a training with Volunteers and Ukrainian partners; took the 7-hour train back to Kyiv Saturday morning. Peace Corps in DC agrees on evacuation, finds a charter plane from Jordan, to arrive Monday. PC Ukraine, largest post globally, had 274 Volunteers serving; a large group completed service earlier that winter. Imagine doing this with the full 350 PCVs, I thought. We tell all Volunteers to get to Kyiv by Sunday night; they do. We get them to the airport — which is closed, skeleton staff. Still only seven cases in Ukraine. We wait. Flight delayed several times, then, about midnight, canceled. Hotels were closing. We found rooms in three; staff bought PCVs water and food, since restaurants were closing.

Tuesday’s charter: delayed then canceled. The company hadn’t arranged landing fee payment, secured a ground crew, etc. Wednesday: flight delayed several times, then canceled last minute. Despite support from the U.S. Embassy in Amman, the government of Jordan wouldn’t let the plane leave because of new COVID restrictions. Wednesday night I propose asking the U.S. military if we can fly Volunteers out on a military aircraft. And I talk to the CEO of a small startup airline in Ukraine interested in making its first flights to the States.

Thursday, 19 cases. We’re getting inquiries from congressional offices about concerned Volunteers’ parents: What’s going on? Thursday: delays, cancellation. Peace Corps HQ locates a different charter company from Spain. I insist on being put directly in touch with them. Thursday night 10:30 p.m., wheels up Madrid. We move PCVs in six different buses, with police and Regional Security Officer escort since it is now illegal to gather more than 10 people. At Kyiv airport, there’s a technical issue: They can’t issue or print boarding passes. So airport staff write them out by hand. Check-in took 10 hours. Friday morning, 6:20 a.m., plane departs. Kyiv to Madrid to Dulles to homes of record.

The real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter.

When I say we it’s the incredible PC local staff. Many had been through evacuation before, in 2014. I managed an evacuation in Papua New Guinea years ago but much less hectic and with only 22 PCVs. This time I was managing it from my Kyiv apartment — Friday I received notice that I had to self-quarantine because I had returned from Europe within the past two weeks. So I’m calling every Volunteer I could to say goodbye during that overnight check-in. During all this we’re posting on social media every day. This was time for gratitude: to counterparts and local staff, host families and government ministry partners, superstar volunteer wardens and our dear Volunteers. I encouraged the Volunteers to stay in touch with counterparts, work remotely if they could — on grant proposals, civic education with youth, English clubs on Zoom, anything; 100 evacuated PCVs have put in nearly 2,000 hours of virtual volunteering already.

Staff here have restarted programs before. They are working hard even without PCVs in country to maintain meaningful contact with counterparts. They know how to do it.

As for unfinished business, there’s goal one for Peace Corps — work Volunteers do in teaching, youth and organizational development. That’s important, but the real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter. When I talk to counterparts, local staff , and Volunteers, I emphasize this. Counterparts love it: Work, yes, but also inviting Volunteers to birthday celebrations, funerals, and weddings, berry picking in the forest — that makes this experience unique and awesome. The Third Goal, that’s unfinished: making America less insular — helping Americans appreciate the realities of life in different places. Those three goals, equally important, are the beauty of our wonderful organization.

Ghana: Gathering for a baby-naming ceremony. Photo by Meg Holladay

Gordon Brown | Country Director, GhanaIT HAD ALREADY BEEN A TOUGH YEAR for us in Ghana. In October, one of our Volunteers, Chidinma Ezeani, died after a tragic gas accident in her home. Thirty-nine Volunteers had to be relocated out of the northern part of the country because of security concerns across the border. Peace Corps Niger is closed because of security; Burkina Faso, too.

Then the virus: by March, regular emergency meetings at the embassy. Countries started closing, restricting airspace. It looked like Ghana was going to close — within the span of probably half a day. Sunday night, they said, Go in tomorrow and tell all 80 Volunteers to move. How fast can you do it? Now, our organizational culture in Peace Corps is not like the military: Here are your orders, execute. But in a moment like this, it has to be: Do this now — like now now.

My former boss used to say, “Being Peace Corps country director is the best job in foreign affairs.” I started as country director in Benin in 2015, then in Ghana in 2018. Along with the joy of the work also sometimes comes tragedy. So how do you be the best when times are the worst? Executing an evacuation takes massive logistical effort and focus. It was us all together — the Volunteers and the agency — that were able to make that happen. We had planes that were supposed to show up that didn’t. When we did get a plane — well, it had been a tough week for me personally, too. My wife had injured a muscle in her leg. So it’s 80 Volunteers, my wife in a wheelchair, our 3-year-old, our 7-year-old, all of our luggage — you can’t make up that level of difficulty. It was level 10.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

As hard as this has been, here’s something that I think has become clear to a lot of the Volunteers: You don’t stop being a Volunteer just because you’re no longer at your site in a country. We’ve got the technology now that allows many Volunteers to be connected all the time. But that doesn’t change the fact that you need to be able to communicate with people in front of you. You need to be able to read people’s emotions and speak with them in a way that is that being empathetic to what they’re going through.

We have to wrestle with what Peace Corps means in the modern world. How does it remain relevant? Ghana is the oldest Peace Corps operation in the world. It started in another era; 1961 was the year of Africa, when some 20 nations became independent. In 1960, the Prime Minister of England, Harold Macmillan gave a speech about “the wind of change” blowing through the continent.

In Ghana, one question is: How do we keep Peace Corps from seeming like a piece of old furniture? It has always been there. Kwame Nkrumah is always a big hero. John F. Kennedy is a big hero. America and Ghana have always had a close relationship. But how do we renew excitement among the government and people of Ghana — to understand that these Volunteers who are capable and tech-savvy, involved and committed, have something to offer? It’s a welcome challenge.

For the agency this is a massive undertaking in terms of charting the way forward: what the focus areas are going to be, what the footprint is going to be — what sectors, sizes, countries? All of that is going to have to be decided on an individual basis. As I like to tell Volunteers: Any victory lies in the organization of the non-obvious.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

Morocco: Girls’ hiking expedition. Photo by Gio Giraldo

Sue Dwyer | Country Director, Morocco

WHEN WE STARTED an in-service training there were maybe two cases in Morocco — a country of 35 million. But come Friday morning, March 13, I don’t like where this is going. They shut down flights to Italy, are talking about shutting down flights to France — our primary means of getting out. We cancel the last few days of training. We send Volunteers back to their sites, put them on standfast.

Saturday morning, I call the Deputy Chief of Mission at the embassy and tell him I think I have to get Volunteers out; if we have to med-evac someone, we’re in trouble. We’ve got 183 Volunteers and Morocco is the size of California. For some Volunteers it takes two days to get back to site; they get a day to pack, say goodbye. In Rabat I figure we’ll have three days for a program to wrap things up. The embassy says you’ve got until next Saturday … then Thursday … then Wednesday. OK, here we go. The Moroccan government keeps moving the time when we can fly. I realize, as this is happening, that I still have some muscles working from my humanitarian aid days; I evacuated NGOs out of Liberia in 1999 during the civil war.

A lot of Volunteers email me saying, “Please don’t send us home, we want to be here in solidarity with the Moroccans.” But they come. Some have problems getting back to Rabat — harassment on buses, people saying foreigners brought in COVID. So our Moroccan staff charter buses and send them out to consolidation points.

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh.

At the airport we have a charter flight with maybe 225 seats for Volunteers only. They start calling: “My grandmother and my mother are here — and the airport’s closed.” So we say yes. Then: My parents, my aunt , my brother. So we have to finish what we started. Thursday at 2 a.m., the plane takes off. Second-year Volunteers knew they were being COS’d. First-year Volunteers were told they were on administrative hold. While they were flying that changed. They got off the plane, they got a different message. That was soul-crushing.

Peace Corps Morocco is one of the oldest programs, and currently the only one in the Arab world. We’re the largest youth development program; it’s our sole area of focus. The evacuation was a huge earthquake with all the aftershocks. And it’s not just for Volunteers. We’ve got host families calling and saying, “I can’t reach my volunteer daughter, son” — because their number changed. “When we see what’s happening in the United States, we’re really worried. Are they OK?”

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh. If we were to do training in a completely different way, what would that look like? So this is an important time for innovation and rethinking our models

.

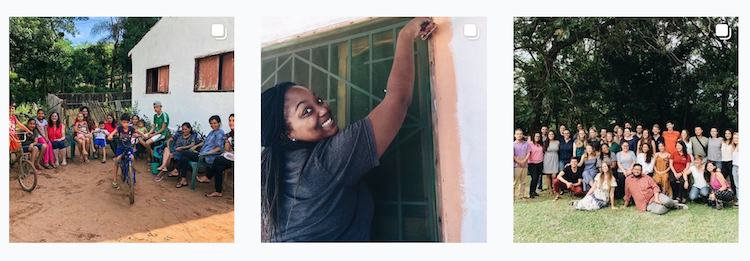

Paraguay: Scenes from an Instagram feed before evacuation

Howard Lyon | Country Director, Paraguay

WE KNEW THE VIRUS was on its way, burning across the world. It was going to hit Paraguay sooner or later. Infections had begun in Brazil. At the time we thought maybe we could ride out the storm. But the world was getting stormier. Then with the infections in the United States, we began getting inquiries from parents: “Where’s my daughter?” “What’s your plan?” I had traveled to the region called the Chaco — very isolated and hot, and there was the theory that the virus doesn’t like heat. That was my last trip to the field.

By March 15 it was very serious. A strange morning, overcast, leaves beginning to fall; autumn was just beginning. Walking to our office I was the only person on the street — a major thoroughfare in Asunción. People were beginning to stay at home; the government was making noises about curfews. We started preparing for lockdown. This happens to be my second evacuation in two years; in 2018 we evacuated Nicaragua — though under very different circumstances. But it’s heartbreaking to take Volunteers from their communities.

Sunday night we got the call. We had a week to get 180 Volunteers out. Paraguay is an inland island, surrounded by Brazil, Argentina, and Bolivia. Politically it was isolated for years. You fly to North America through São Paulo, Buenos Aires, or Santiago, and then another connection. We got word that Panama, a central hub to get people to the U.S., was going to close. By Wednesday word was the airport in Asunción might close. We even had a group on a bus to the airport when our travel agency canceled our tickets. So we brought people back to their hotel. Saturday, we got a chartered flight, our last large group. Lockdown began the night before; we weren’t even allowed to leave our homes to say goodbye to them. So it’s all WhatsApp, and we’re calling, we’re saying goodbye in other ways.

THREE MONTHS LATER, Latin America is being harder hit. Volunteers I speak to express gratitude to the country, sadness for leaving their communities here, but also gratitude for being close to their families in the U.S. during this time. In Paraguay, we were on strict lockdown the first month, and that helped. In Peru and Ecuador, it’s a terrible situation. Brazil is horrific. Here the population is about 7 million. We’re around 1,300 cases now; there have been 12 fatalities.

Our staff have been talking to community members and counterparts. They want everybody back. But it’s going to be a different world. In Paraguay, kissing and hugging are a big part of the culture; so is sharing food, or drinking tereré out of the same gourd or straw. That will change. If the opportunity presents itself to return Volunteers, they will be well received by their communities. But we’re going to have to think about how you go in as the foreigner who has been in a country with such high infection rates.

Another crucial factor: New and returning Volunteers alike have not only lived through an extraordinary world health catastrophe, but the recent murders of Black Americans, which are a consequence of centuries of racism, have brought another time of protest and a time of reckoning. All of us as individuals and as organizations have to look within ourselves and truly recognize that this situation — the mistreatment of people because of race — is the heritage of our country. We have to deal with it. It doesn’t mean everybody’s bad, doesn’t mean everybody’s good. It just means we’ve got to live together.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class.

When the Black Lives Matter movement began a few years ago, there were repercussions in the Peace Corps. Some wanted the agency to answer hard questions. This is now even stronger and more tragic. The economy and unemployment, the illness and who it affects most, and the reckoning with justice: It’s an extraordinary time. So our staff need to be compassionate and understanding.

I haven’t been to every country in the world, but I’ve seen a bunch. And I don’t know of any non-racist country, especially in this part of the world. Africa was colonized by Europeans who, to do what they did, dehumanized native populations. That curse has been with us ever since. In this part of the world, when we talk of Europeans — the Spanish and the Portuguese — this conquest was very violent. These nations were born in violence, but they’re trying to reckon with it.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class. Every one of us is facing uncertainties — and we’re social distancing, losing human contact. I hope compassion is what we learn out of all this. It’s not just, OK, lights are on again.

As I said to the last group flying out, when I called and they put me on speakerphone: We truly love you guys. We love you Volunteers.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thank you for reading: We try to bring you stories that matter to our community. We welcome any support you can give for the work we’re doing.

-

Steven Saum posted an article“Mongolia loves Peace Corps,” Lucy Baker says. “And Peace Corps Volunteers love Mongolia!” see more

Nobody wanted it to happen this way. Evacuation stories and the unfinished business of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world.

Photo: Ceremonial first haircut for a young girl. Volunteer and photographer Antonio Mercatante was invited to observe.

Mongolia | Lucy Baker

Home: San Francisco Bay Area

As Volunteers were being evacuated from China, in Mongolia, Lucy Baker and others watched their country go into lockdown. The government declared that February celebrations for Tsagaan Sar, the Lunar New Year, would be suspended. There were no confirmed cases of coronavirus, but the government wasn’t taking chances. And Volunteers were told to “stand fast.”

Baker lived in Bayankhongor, a city of 30,000 in the southwest. She served as a health Volunteer, teaching in a high school and helping colleagues implement a new health curriculum. She led summer health camps and served as a Volunteer “sub-warden” — a leader in times of crisis. She studied biology at Emory University, hoping to better understand how infectious diseases affect our bodies and, as she says, “how the world reacts to them.” Like now. In college, she also went to Botswana to study HIV/AIDS.

She arrived in Mongolia in June 2018 and was closing in on the completion of a normal term of service. She planned to stay on as a volunteer leader for a third year: working with an NGO in the capital, Youth for Health, which provides screening and testing for sexually transmitted diseases, as well as counseling for youth on stigma over same-sex relationships. “Mongolia loves Peace Corps,” she says. “And Peace Corps Volunteers love Mongolia!”

“Then the email: I had about 36 hours to pack up everything and say goodbye.”

Wednesday, February 26, walking home from visiting a friend: “My site mate called me in tears: ‘Lucy, we’re being evacuated.’” Korean Air, which provides the majority of flights out of Mongolia, had ended service. “Then the email: I had about 36 hours to pack up everything and say goodbye.”

Teachers came over at midnight to say farewell. That was hard. Baker told them, “I’ll be coming back, you know.” That was the plan; she and the newest cohort of Volunteers would return.

Lucy Baker, center back, was invited to be a counselor for an environmental conservation camp called Junior Rangers. “We taught lessons on climate change, first aid, did science experiments, chaperoned dances, and gave out tissues when crushes didn’t end well,” she writes. “The kids wrote us little notes when camp was over, and I still have them to this day.” Photo courtesy Lucy Baker

Baker came home to family in the Bay Area. That was before the area’s shelter-in-place order. And it was a good ten days before the rest of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world got the news that they would all be leaving. And Volunteers from Mongolia got the word that their service was being closed. —Steven Boyd Saum

See more photos from Lucy's service

Mongolia | Daniel Lang

Home: Originally the Midwest — Now North Las Vegas, Nevada

I'm Daniel Lindbergh Lang, a Peace Corps Volunteer from the American Midwest then Nevada. In Mongolian, “Намайг Даниел гэдэг.” (I’m called Daniel.)I served nine beautiful months in Mongolia, where I contributed to English education and community development. Having entered Peace Corps with a degree in journalism, I love arts and culture. So a couple months into my teaching at the university where I worked, I was both delighted and bewildered when my colleague said one afternoon that we wouldn’t need to plan the next lesson. We always tried to plan. No, she explained, we’d take our first-year students to the province museum.

The next October morning, with the snow falling, my colleague rolled up in her car at the bottom of the hill from where my Soviet-era apartment stands. I felt grateful for the ride. Usually I have to walk into town.

English club meet-up: A big turnout for the first meeting of the school year. Photo by Daniel Lang

Inside the museum I took off my coat but kept on my plaid scarf. (Mongolians love my plaid accessories.) Students looked elated to see me. They’d only known me a month, since Mongolia’s school year began September 1.

We saw paintings from Mongolia’s Soviet-partnered past — and, across the way, various stuffed creatures. My students called me over, speaking Mongolian and broken English, asking for help understanding a sign. I helped a student double-check a phone dictionary to confirm: We indeed stood before a “squirrel.”

In the museum’s later halls, my colleague called me over and spoke cheerfully about ceremonial outfits and the objects Mongolians use at holidays. I’d seen some of these while with my host family during my Peace Corps training summer in the countryside. But I’d never seen anything like what was waiting in the final room: the largest морин хуур (morin huur, or “horse fiddle”) I had ever seen. A giant could have dropped off that marvelous Mongolian, two-stringed instrument — with its trapezoidal body and long, elegant neck. In just a few months I had heard many performances on the normal-sized equivalents. My colleague made sure to get a photo with me with it for Facebook.

I gave them grammar guidance. They gave me a new way of seeing.

The next class I taught with that colleague, we critiqued students’ museum presentations. And while they truly were far from perfect, I loved getting to hear how they described the exhibits. I gave them grammar guidance. They gave me a new way of seeing.

When we were evacuated from Mongolia in February, I left behind students, colleagues, and community members eager to improve their English.

At the university, I taught undergraduates on paths to becoming instructors, businesspeople, and diplomats. Mongolia only began English education in the 1990s, making today’s Mongolians still among their nation’s first English language learners.

At night, fellow Volunteers and I taught English to learners of all ages. I worked with community groups at our city library, young professionals at our local Toastmasters, and doctors and nurses at a hospital. I spent my Saturdays with teachers and children at an orphanage. Sundays, after mountain hikes and Mass, I also taught lessons in Chinese.

Days before I left, I had met with local officials to found a camp to help rural students become mentors. I met new collaborators for furthering language learning for Mongolian youths. At Mongolian Lunar New Year celebrations, I ran into community members who had learned English from Peace Corps Mongolia’s first cohorts, over two decades ago.

The people I worked with — months later, we keep in touch. Back in the States, I helped colleagues secure an acceptance with the first research article from Mongolia in one international peer-reviewed journal. A speaking club I frequented has invited me to video chat with them. A Mongolian youth group has invited me to help them practice English. I’ve gladly taken part.

Read more from Daniel Lang at: www.memoryLang.tumblr.com/PeaceCorpsStories.

See more from Daniel's service

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate... see more

Thank you for bringing the "other side" of the Peace Corps evacuation. We have read how difficult it was for each PCV to leave their host country, friends and projects. Now, we can appreciate what a herculean effort was made by PC staff to evacuate all Volunteers, safely.