Activity

-

Tiffany James posted an articleRecognition for three members of the Peace Corps Community. Plus a new legislator. see more

Recognition for three members of the Peace Corps community. And an RPCV appointed to the North Carolina Legislature.

By NPCA Staff

Photo: Shelton Johnson, recipient of the 2022 American Park Experience Award. Courtesy National Park Service

Shelton Johnson | Liberia 1982–83

Shelton Johnson received the 2022 American Park Experience Award for his years of advocating for diversity in national parks and helping families and youth feel welcome by seeing their stories told there. Johnson has worked for the past 35 years as a ranger with the National Park Service at Yellowstone and now Yosemite National Park. His storytelling talents landed him a prominent role in Ken Burns’ The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. In 2010, Johnson hosted Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King on a multi-day camping trip that was captured on national television and broadcast around the globe. He credits his work with Oprah as a significant breakthrough in introducing Black Americans to the wonders of America’s national parks.

Lawson Scott Glasergreen | Guatemala 1994–96

Peace Corps Volunteers have never served in Antarctica — but Lawson Scott Glasergreen, currently a FEMA contractor, celebrated what he believes to be the first Peace Corps Week there in 2015. Last year he was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal by the Secretary of Defense for his work at the South Pole in 2014 and 2015, during the continent’s summer months. Glasergreen worked as a preventative maintenance coordinator and supervisor for on-site infrastructure and operation management practice and program management leadership on a Pacific Architects and Engineers contract with Lockheed Martin.

Inspired by his experience in Antarctica, Glasergreen is publishing a volume of writings and photographs. That follows on a previous book of journal entries and artworks, SPIRITO America, about the gifts of personal and social service. Glasergreen is also a visual artist and has Cherokee roots. He was among a dozen Indigenous artists featured in Native Reflections: Visual Art by American Indians of Kentucky, a traveling exhibition that completed a two-year tour of the state in Louisville in March 2022.

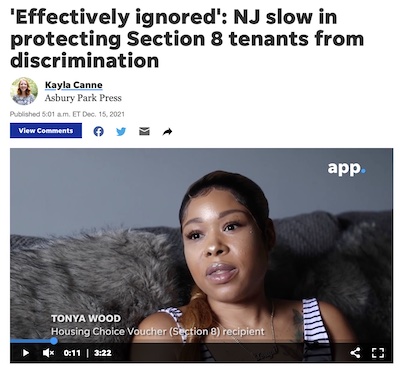

Kayla Canne | Ghana 2018–20

Journalist Kayla Canne won a National Press Foundation award for her work with the Asbury Park Press investigating deplorable living conditions and discrimination in taxpayer-funded rental housing in New Jersey. In the series “We Don’t Take That,” Canne exposed the barriers that exist for low-income tenants in their search for clean, safe, and affordable housing.

Caleb Rudow | Zambia 2012–14

Caleb Rudow was appointed by North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper to the state legislature on February 1. He is serving out the remainder of the term for Rep. Susan Fisher, who represented District 114 and stepped down December 31. The term Rudow now serves ends in January 2023. Redrawn electoral maps were unveiled February 23. The new boundaries have Rudow running for reelection next year in neighboring District 116 — in the Asheville area, like his current district. Prior to this role, Rudow worked as a research and data analyst at Open Data Watch in Washington, D.C., where he conducted research on open data funding, patterns of data use, and technical issues around open data policy.

This story appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated May 3, 2022.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleUnderstanding identities through oral history interviews with 50 Africa-born immigrants in Kentucky see more

Voices of African Immigrants in Kentucky

Migration, Identity, and Transnationality

By Francis Musoni, Iddah Otieno, Angene Wilson, and Jack Wilson

University Press of Kentucky

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

The heart of this book is based on oral history interviews with nearly 50 Africa-born immigrants in Kentucky — of which there are now more than 22,000. From a former ambassador from The Gambia to a pharmacist from South Africa, from a restaurant owner from Guinea to a certified nursing assistant from the Democratic Republic of Congo, every immigrant has a unique and complex story of their life experiences and the decisions that led them to emigrate to the United States. The geography of stories reaches from Algeria to Zimbabwe, Somalia to Liberia, grouped together with stories of origins, opportunity, struggles, and success, and connecting two continents.

Within scholarship on migration and identity, this book “offers a refreshing step away from existing research on major urban centers that host large populations of African immigrants,” notes a review in the Journal of Southern History. “It is especially relevant to the study of ‘new African diasporas,’ which focuses on African diaspora communities who have arrived directly from Africa in recent decades and whose sense of history, race, and identity is understandably different from the many other African diaspora communities in the United States.” And at a time when migration continues to roil U.S. politics, the book also offers new insights into transnational identity. With that in mind, the final chapter takes as an epigraph an Igbo proverb from Chinua Achebe’s novel Arrow of God: “The world is like a Mask dancing. You do not see it well if you stand in one place.”

The project brought together Angene Wilson and Jack Wilson with historian Francis Musoni, who was born and raised in Zimbabwe and teaches the University of Kentucky; and Iddah Otieno, a professor of English and African Studies who teaches at Bluegrass Community and Technical College and is originally from Kenya.

This review appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated May 2, 2022.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleHe served as a U.S. consul in Iran, and in Isfahan witnessed a revolution unfold. see more

With the Peace Corps, he and his wife helped set up the first high school for girls in the town of Farah. As a diplomat in Iran, he helped evacuate hundreds of U.S. citizens.

Photo courtesy the family of David McGaffey

By NPCA Staff

Born on a farm in Michigan, David McGaffey was 15 years old when he enrolled at the University of Detroit. He studied theater, folklore, psychology, and math, and met his future wife, Elizabeth. They wed and applied to serve as Peace Corps Volunteers in Chile.

“The Peace Corps looked at my application and said here is somebody who likes mountains,” he recounted, “and called me up and said, ‘How would you like to go to Afghanistan?’”

The couple served 1964–66 in Baluchistan, setting up a science lab and the first high school for girls in the town of Farah.

He joined the foreign service and went to Manila. He returned to Afghanistan as an economic officer and saw firsthand the battle for influence between the U.S. and USSR. He served as a U.S. consul in Iran, and in Isfahan witnessed a revolution unfold. He organized evacuations of thousands of Americans.

He was nearly killed himself while trying to defuse the aftermath of a knife-turned-shooting argument over a shady business deal between a U.S. employee of Bell Helicopter and an Iranian taxi driver. The hotel where they were ensconced was surrounded by a mob of thousands ready to burn the place down, and police refused to intervene. McGaffey enlisted help from mullahs and got them and the American into a car to escape. “But I didn’t get in and was seized by the mob, shot, stabbed, hanged, and had both of my kneecaps broken.”

McGaffey received an award for heroism.

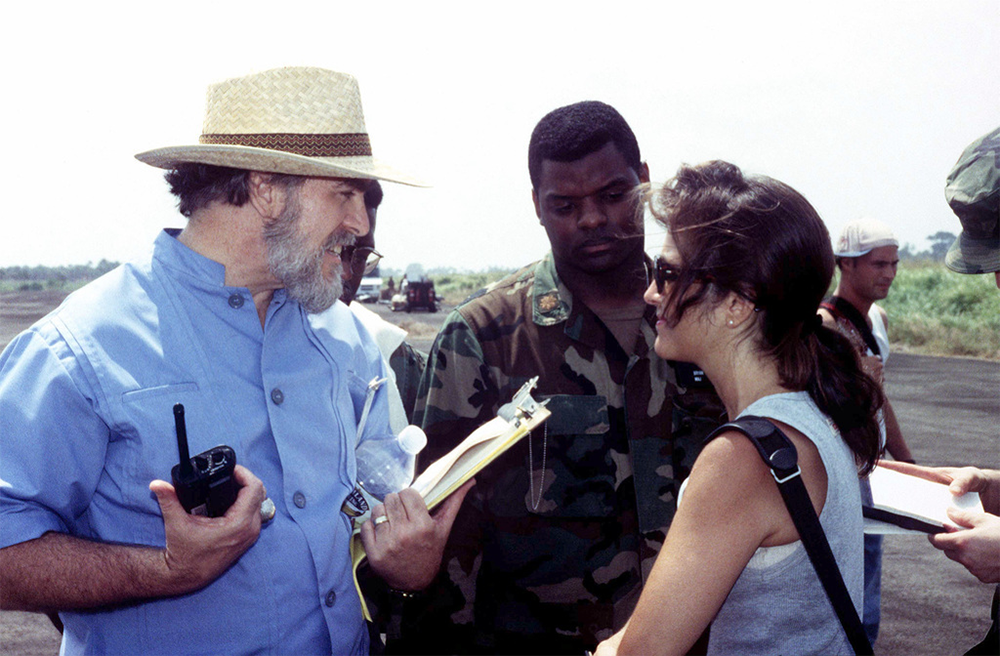

Operation Assured Response, 1996: David McGaffey, left, was working with the U.S. Embassy in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Here he talks with U.S. Air Force Major Bryan Holt and a reporter while awaiting the arrival of evacuees from Monrovia, Liberia. Photo courtesy Department of State

McGaffey served some months in Tehran with the embassy before departing in fall 1979; 40 days later the embassy was stormed. He served as deputy chief of mission in Guyana and as U.S. representative to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

He wrote four volumes on diplomacy and a children’s book. He finished a master’s at Harvard’s Kennedy School and a doctorate in international relations at Johns Hopkins. He taught at universities in the U.S., Portugal, and Sierra Leone. He died in April at age 79.

This story appears in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleDiversity is only a demographic concept. The effort starts at belonging. see more

Part of the discussion on “Building a Community of Black RPCVs: Recruitment Challenges and Opportunities”

Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

By Sia Barbara Kamara

Peace Corps Volunteer Liberia 1963–65 | Educational Consultant

I live in Washington, D.C. But I grew up in what would be considered public housing in North Carolina. I graduated from Johnson C. Smith University, a historically Black college. The Peace Corps recruiter came to campus just before graduation. I said, Yes, if I can go to Africa. I graduated with a degree in mathematics and physics, and a minor in economics. My goal was to be a scientist.

When I went to Liberia, my parents were very supportive. They always had African students at my college come home and visit. During my time in Peace Corps, when so many African countries obtained independence, every time a country changed its name, they got a new atlas. They sent Ebony magazines to me. I was way up-country, and there were four African American Volunteers in my group; by the time that magazine reached me, it was all dog-eared, because people along the way would read it.

I was a teacher and worked with young women; we created a track team, and they went on to be national champions. As a Volunteer, I had been treated like an African queen; people welcomed the Black American. But they said, “We don’t let foreigners teach below third grade.” That’s when children learn about their own culture, and they learn it from people around them. Eventually they did allow me to do it.

A life of learning: Sia Barbara Kamara with a student in Liberia, where she served with the Peace Corps. She now advises the Ministry of Education of Liberia. Photo courtesy Friends of Liberia

When I returned to the States, I served as a Peace Corps recruiter in the Northeast. Sargent Shriver would have me lead sometimes, because he thought that it was important for people of color to be seen in leadership positions. Then I served on the team recruiting at historically Black colleges. I left to become an intern in a program organized by the wife of a former Peace Corps country director in Nigeria, helping historically Black colleges obtain resources. I wrote grants to expand an early childhood program. I knew little about what I was doing, but Peace Corps gave me the courage to do almost anything. I worked with a superintendent of schools and helped organize a master’s program for African Americans to obtain degrees in early childhood education. I had the opportunity to visit early childhood programs in every Southern state and document what they were doing. I presented a paper and met the president and dean of Bank Street College in New York. They asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

The president and dean of Bank Street College in New York asked, “Where did you get your master’s in early childhood?” I said, “I don’t have one.” They said, “You’re enrolled.”

I went on to work in North Carolina, responsible for an eight-state Head Start training program. Then I went to work for the governor of North Carolina. President Carter asked me to come work as an associate commissioner in the Department of Health and Human Services, responsible for the national Head Start program, the Appalachian Regional Commission child development programs, childcare regulations, and research and demonstration programs. Then I worked for four mayors in Washington, D.C., to help transform the early childhood system. For the last 10 years, I have been a consultant in early childhood to the Ministry of Education in Liberia. I’ve returned to that place where I got my start, working in Africa.

Early childhood educational center: Sia Barbara Kamara, right, and a sign announcing the work of a center named for her. Photo courtesy Sia Barbara Kamara

When I think about current and returned Volunteers, many need support — networking opportunities, validation, mentoring. It’s important that we continue to provide these during training and reentry, and as people are in service.

People in Liberia have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

I’m very active in our Friends of Liberia group. However, I’m the only African American in our education work group. We have been able to focus on building human capacity to help groups obtain the resources and background and know-how they need to sustain programs. People there have the skill, knowledge, will, and commitment to do for their own country. We can help identify funding opportunities, and be a mentor and coach.

Going forward, Peace Corps needs to understand what Volunteers are experiencing during training or when they go out. I had spent four years going to jail as part of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. When we were undergoing Peace Corps training in Syracuse, New York, they didn’t want us to go and participate in a march. That was a part of my DNA. It went all the way to Washington for Sargent Shriver to have to make a decision. We marched together.

These remarks were delivered on September 14, 2021, as part of “Strategies for Increasing African American Inclusion in the Peace Corps and International Careers,” a series of conversations hosted by the Constituency for Africa and sponsored by National Peace Corps Association. They appear in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022.

Sia Barbara Ferguson Kamara received the Peace Corps Franklin H. Williams Award for Distinguished Service in 2012. At Head Start, she managed a budget of approximately $1 billion. When she started, there were 100,000 children in the program; it grew to serve 122 million under her watch.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleA diplomat committed to peace and prosperity in the Caribbean see more

He began his career as a teacher with the Peace Corps | 1949–2021

He was a diplomat who devoted decades to advancing peace, prosperity, equality, and democracy in the Caribbean. Peace Corps service set him on that path. Equipped with a bachelor’s from Emory University, he headed to Liberia as a Volunteer (1971–73) and taught general science, biology, math, and chemistry. He admired the commitment of U.S. Embassy staff he met.

He completed graduate degrees in African studies and education, then embarked on a career that took him to the Dominican Republic, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Ecuador before he was appointed ambassador to Honduras (2002–05) by President George W. Bush. He served as president and CEO of the Inter-American Foundation, focused on grassroots development in Latin America and the Caribbean, expanding support for underserved groups, including African descendants.

President Barack Obama tapped Palmer to serve as U.S. Ambassador to Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean (2012–16); Palmer concurrently served as ambassador to Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. He understood the value of building relationships in person.

A moment with the press: Larry Palmer after speaking with the president of Honduras in 2002. Photo by Esteban Felix / AP

A story he shared, from a conversation with Alejandro Toledo, who, Palmer said, “always talks about his experience as a young student when a Peace Corps Volunteer identified him as a potential excellent student and leader and pushed him and gave him the courage that he needed to move on, further his education … And of course he ended up as president of Peru.” Larry Palmer died in April at age 71.

—Steven Boyd Saum