Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleA conversation with Mark Gearan and Keri Lowry see more

From Peace Corps to AmeriCorps to envisioning a quantum leap: 1 million people in the U.S. serving every year — and changing the culture and ethos of service. So how do we get there?

A conversation with Mark Gearan and Keri Lowry.

By Steven Boyd Saum

In 2017, the U.S. government undertook the first-ever comprehensive and holistic review of all forms of service to the nation, and Congress wrote into law the creation of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Over many months, this 11-member bipartisan commission embarked on visits to 42 cities in 22 states, to listen and learn. One area they were charged with examining: military selective service. Then, more broadly: how to expand all kinds of service — domestically and internationally.

The commission issued its final report, including a raft of recommendations, in March 2020 — as a pandemic swept the country. Media attention was minimal — which was both understandable and ironic, given that the crisis underscored the need for service, such as “a Peace Corps for contact tracers.” Even so, recommendations in the report began shaping proposed legislation. And, as this year has shown, there are much bigger changes afoot.

As for selective service: The commission recommended that all citizens, regardless of gender, be registered. That is reflected in next year’s Defense Authorization Act, currently making its way through Congress.

MARK GEARAN served as vice chair for the commission. He was director of the Peace Corps 1995–99 and president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges 1999–2017. Since 2018 he has led the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics.

KERI LOWRY served as director of government affairs and public engagement for the commission. She served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Burkina Faso 2000–02. She has gone on to serve on the National Security Council; as regional director for the Peace Corps for Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa; and as deputy assistant secretary of state. She is currently in the National Security Segment of Guidehouse.

Steven Saum: Let’s start with the big question behind this whole endeavor: If we’re talking about it on a national stage, why does service matter?

Mark Gearan: It goes to the very fabric of our life and civil society. The work can make a real and meaningful difference in communities, in terms of actual outcomes, both domestically and globally. It’s also a powerful statement about our society: about people giving back and caring about others, to share skills and work for the public good. There’s an individual and a collective dimension. And at a time when our nation has these deep divisions, service can be a uniter. It can allow people to work across the whole spectrum of differences that may separate us. Common purpose for the public good is vital for our society’s health and well-being, and for our nation’s security.

Saum: Talk about where we were as a country when this project began — your sense of what was at stake. And how has that changed since the report came out last year?

Gearan: What Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Jack Reed (D-RI) did was really unprecedented: bring together military, national, and public service. It offered a different look, because it affected the very structure of the commission; those appointed by congressional leadership and the president reflected a diversity of experience — military backgrounds, congressional staff, people who had held elected office, some of us directly associated with national service. I liken some of the work we did to de Tocqueville’s tour of our country in his great book: We traveled, did extensive listening sessions.

There is so much good work going on around the country — that’s the good news. But the potential is largely untapped. That led to recommendations that, at the beginning, I would not have imagined. Civic education, for instance, came up through the listening. The report gives a comprehensive road map — and it offers an expansive vision that strengthens all forms of service to meet the needs that we have, and in so doing, strengthens our democracy.

Keri Lowry: The listening sessions helped us understand different facets, the actors in various spaces, how much overlap there was, and ways they could work together to start to bridge divides. The report does a great job of helping put those pieces together. The question is, what is the right ignition to get it going?

Illustration by James Steinberg

Gearan: Service is a fundamental part of who we are as Americans, and how we meet our challenges. But we’re a big country, 330 million people. By igniting the extraordinary potential for service, our recommendations will address critical security and domestic needs, expand economic and educational opportunities, strengthen the civic fabric — and establish a robust culture and ethos of service. Legislatively, part of this effort is in the American Rescue Plan, passed in March 2021; there’s $1 billion for AmeriCorps. That doubles AmeriCorps funding. There is growing support for bipartisan efforts, like the CORPS Act, introduced by Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) and Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS). Hopefully, the broader point will extend to Peace Corps and other streams of service.

Lowry: One great example of where the commitment to service comes together: In 2020, evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers were able to pivot their service when they came back and help domestically, based on what they learned overseas. A lot of them integrated with AmeriCorps efforts. It was very organic.

Gearan: When I served as Peace Corps director, we had 10,000 applications for 3,500 slots every year. I can’t attest that all 6,500 who were not invited would be qualified. But Americans, confronted with those facts, would say something’s fundamentally lacking—that you have thousands raising their hands to serve, and we would not support them. We saw that domestically as well, on our tour, this untapped potential.

We’ve had 235,000 Americans who’ve served in the Peace Corps and over a million in AmeriCorps. There’s growing interest. We can, by 2031 — the 70th anniversary of President Kennedy’s call — envision a million Americans will begin to serve in military, national, or public service every year. That’s a significant scaling up. When I was director, we had the campaign to get to 10,000 Volunteers by 2000. We got authorizing legislation done. The appropriations weren’t there.

The long-term goal is to cultivate a culture and ethos of service, in which individuals of all backgrounds expect, aspire, and have access to serve. This comes with bipartisan support. The chair of the commission was a former Republican congressman. We had folks appointed by Senator Mitch McConnell, Speaker Paul Ryan; I was appointed by Senator Reed—so the commission did represent a broad ideological spectrum. At the end, we were united in our recommendations.

Lowry: One thing that became clear fairly quickly in the listening sessions is how little people knew about opportunities to serve — or the variety of venues. They might know about one component of service, but not others.

Gearan: One recommendation is the creation of a White House Council to coordinate service efforts across the federal government, to make service more focused and effective — and draw a brighter spotlight on it. Another is to have an online platform providing a one-stop shop for individuals to explore service opportunities. Low awareness and lack of access are real obstacles preventing many Americans from serving. That would also help service organizations — certainly the Peace Corps — find those with the interests or skills they need to achieve their mission. President Kennedy’s vision with the Peace Corps, continuing domestically with AmeriCorps, supported by present bipartisan administrations and Congress over the years, seems a good foundation to build on. Senator Coons’ work with Senator Wicker and other Republicans to advance the CORPS Act is another recent example of bipartisan support. In terms of AmeriCorps, there are real needs being met — and a documented return on investment. A good body of research shows that for every dollar you put in, there’s $17 returned.

With the tragedies of the pandemic, inequities have been laid bare — unequal access to healthcare, education. That has a motivating impact for many lawmakers: How could service meet some of these needs? The past year has put a sense of urgency on answering that.

Saum: The report was released in March 2020 as the country was going into real crisis with the pandemic — a tough time, yet the need for service was even more relevant.

Gearan: Our target date, March 25, was planned months in advance because of necessary deadlines — including printing. It fell at the height of the pandemic and lockdowns. Having said that, we also included, in addition to some 64 recommendations, legislative language — which was helpful to the Hill for operationalizing quickly. Some recommendations helped shape legislation introduced last year, and more this year — such as with Congressman Jimmy Panetta (D-CA), and his caucus’s efforts; and the efforts that Senator Coons and others have picked up in the Senate.

I have seen more momentum and energy associated with thinking about service in an expansive way than I have for many years. It’s almost always been somewhat of a defensive posture: Save AmeriCorps, advance the Peace Corps budget. Along with the legislative tactical piece, this really brought it to a broader level of conversation. It’s a unique moment.

Significantly, it’s also clear that with the tragedies of the pandemic, inequities have been laid bare — unequal access to healthcare, education. That has a motivating impact for many lawmakers: How could service meet some of these needs? The past year has put a sense of urgency on answering that.

We traveled to 22 states and consulted with hundreds of stakeholders, hearing thousands of public comments. It was three years of work charged by the Congress. The initial focus was the selective service and whether there would be a requirement for all Americans to register; that always has news focus. But there’s been a much more fulsome look at our recommendations.

Saum: One common refrain I hear again and again is: “We need a Peace Corps for this, we need a Peace Corps for that.” There’s a recognition that service, and harnessing the energies of more Americans, might be a way to deepen understanding, address problems, and weave the fabric of the country more strongly.

Gearan: There’s the deep respect that the Peace Corps enjoys — deservedly so, thanks to the work of Volunteers, which has laid out this path in many ways.

AmeriCorps has added to it, certainly. Peace Corps was born in another political time, with a vision and energy that has marked six decades of making a difference; that informs so much of what this broad movement is about. When I would travel and listen to different stakeholders, there was frequently more than just a nod to the Peace Corps; there was a foundational element of understanding the importance of service through people’s understanding of the Peace Corps.

So there are many reasons to be grateful to Peace Corps Volunteers and what they have done. It’s also allowed for this moment — as when President Clinton started AmeriCorps, and people understood the shorthand for it was “the domestic Peace Corps.”

Saum: So where do you see the ignition coming from?

Lowry: Look at the meetings that National Peace Corps Association began convening last year, for Peace Corps Connect to the Future. As came up in discussion there, the private sector has a potentially big role here.

The Employers of National Service, and getting more employers to join — that could be an igniter. Show more benefits to young people — or even not young people: You’re learning skills and capabilities that can help you get a job. My company makes efforts to hire candidates that have military, public, and/or national service on their resumes.

To usher in this new era of service, we need the infrastructure to support a million Americans in national service.

Gearan: To support a million Americans serving by 2031, you have to remove some barriers. We know from our travels that AmeriCorps, YouthBuild, Peace Corps can make a difference, meet challenges. The demand is there. To usher in this new era of service, we need the infrastructure to support a million Americans in national service. Part of it is expanding existing programs. Part of it is creating new models — such as a new fellowship program to allow Americans to choose where they want to serve from a list of certified organizations. We made recommendations for funding demonstration projects to pilot innovative approaches, and to increase private sector and interagency partnerships. You’re not going to get to a million without that.

Look at recent numbers for national service: 7,300 Peace Corps Volunteers, 75,000 AmeriCorps volunteers. We’re a long way from a million. But if we really committed ourselves, it’s achievable. Then it would lead to the next level, as Harris Wofford used to say. It won’t be atypical to ask, “Where have you served?”

Lowry: We want to change that conversation, but also start to change the culture.

Saum: For the Peace Corps community, what’s important for them to keep in mind in terms of national service — and making that quantum leap?

Gearan: First, gratitude. I would hope the Peace Corps community and Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, in particular, would feel proud that their service has ushered in a moment for us to significantly enhance the ethos of service in our country, because their work from the early years through today has prepared a pathway for significant expansion.

Secondly, I hope they would be a part of this movement. Their voice is unique, it is appreciated — and they can speak from experience as we work with legislators to advance this expanded national service movement. I’d hope their attentiveness to legislative work and all the good work of NPCA on advocacy would continue. We’re at a real pivotal moment for expanded opportunities for service.

Lowry: Peace Corps gave me opportunities that I never envisioned. For national service to expand and meet the needs of a broader swath of the American population, we need those voices of returned Volunteers to help make national service meet the needs of individuals today. Just because my Peace Corps service included X-Y-Z, that doesn’t mean that the Peace Corps service of someone tomorrow might not have elements that we haven’t been considering to date, or it just hasn’t gotten over the finish line. Their understanding and their voices can help make national service the best that it can be going forward — for their children and their children’s children.

National Peace Corps Association did a phenomenal job of teeing that conversation up last year. It would be wonderful if there’s a way that we can continue that conversation to make national service even better.

We sit atop 60 years of demonstrated efforts by Americans making a difference. That’s a proud legacy. I would say the best way to honor it is by saying, OK, what is the next chapter?

Gearan: In so many ways, the Peace Corps is kind of the crown jewel of so much great service work. Its roots and foundational ethos, thanks to Sargent Shriver and his contemporaries, so informed the broader movement. And if anyone would be calling for innovation and creativity and expanded slots for the Peace Corps’ next chapter, it would be Sargent Shriver.

We’re in this moment, formed and complicated by a pandemic, with challenges and needs that have been exposed for decades as well. But congressional and state leadership see how service is making a difference. We sit atop 60 years of demonstrated efforts by Americans making a difference. That’s a proud legacy. I would say the best way to honor it is by saying, OK, what is the next chapter?

Saum: What does it mean to serve now?

Gearan: As Peace Corps director, when I was visiting Volunteers or meeting RPCVs, the commonality of experience was striking—whether one had served in the ’60s in Ethiopia, in Poland in the ’90s, or South Africa in the 2000s. The shared experience of making a difference was the through line. And that brilliant Third Goal—the domestic dividend—is one of the underappreciated pieces of the Peace Corps.

We have now 235,000 Americans who have served — many in top-level government, business, education, industry, commerce, law, across the spectrum.

Lowry: Go back to that sense of being innovative and looking forward: Peace Corps’ true roots are in building peace and friendship. This is why we’re serving in communities, not just for a short but for a longer duration of time — to really build and seek to understand.

Read the Report

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView.

-

Joanne Roll I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns... see more I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns during public comments. They were not included. I do not believe I was the only one to question. The problem with emphazing "service" is it objectifies the people receiving the "service". They should be placed first, as they are in the First Goal of the Peace Corps.2 years ago

Joanne Roll I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns... see more I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns during public comments. They were not included. I do not believe I was the only one to question. The problem with emphazing "service" is it objectifies the people receiving the "service". They should be placed first, as they are in the First Goal of the Peace Corps.2 years ago

-

Steven Saum posted an articleAn exhibition by ArtReach Gallery and the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience see more

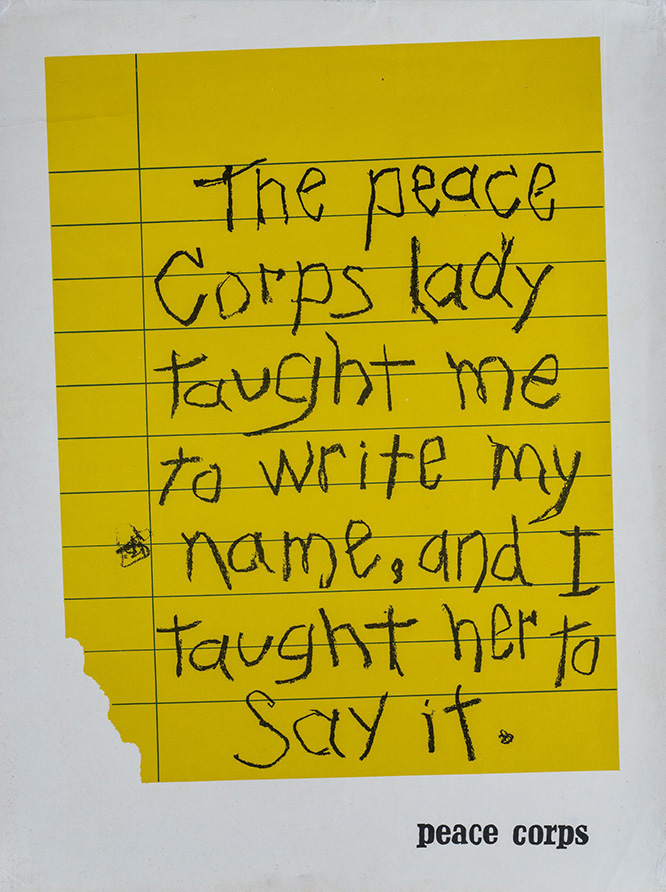

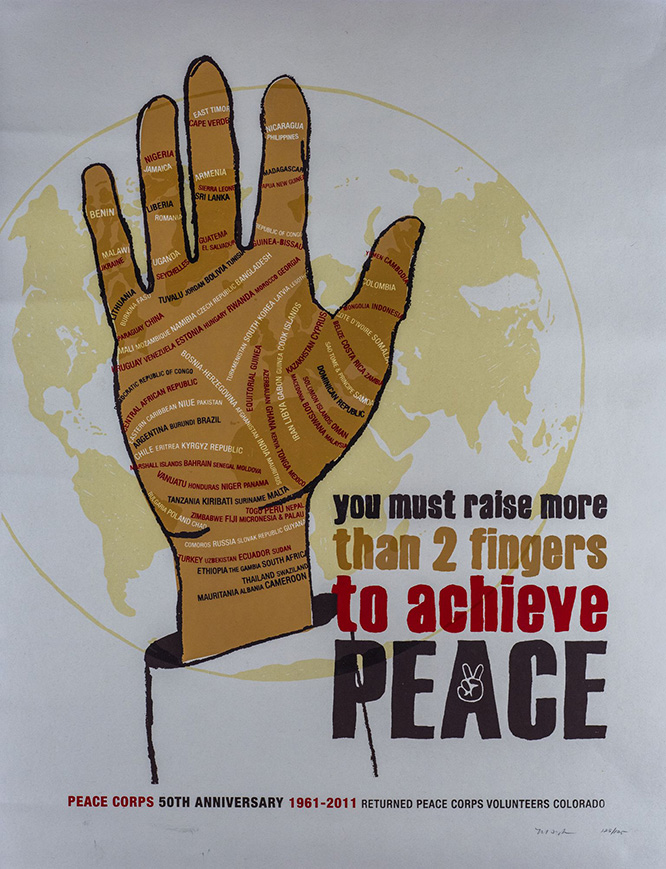

This exhibition by ArtReach Gallery and the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience does more than trace marketing materials for the agency. In images and words — including works by renowned artists Peter Max and Shepard Fairey — it explores how we think about and talk about the idea of peace itself. And how we make it.

Introduction by W. Sheldon Hurst

Curator, ArtReach Gallery

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Peace Corps in 2011, Shepard Fairey created a poster that was widely distributed across the United States. The focus of the two figures is on the fruit of the earth being carefully lifted from the fields below; plants frame this central image. The plant in the woman’s hands is not simply a seedling; it doubles as the sun, radiating both light and life. A closer look reveals, at the center of the sun/plant, a peace sign, inviting consideration of the grounding relationships that bring about the rooting and leafing essential to the work of feeding others as well as ourselves. This idea of multifaceted relationships has been the work of Peace Corps since its creation in 1961.

My wife, Karen Hurst (Tunisia 1966–68), was gifted this poster in 2015 shortly after we moved to Portland, Oregon. Remembering a Peter Max Peace Corps poster from the 1960s, I started to be curious about the posters adopted by the Peace Corps, and about their various purposes.

Posting Peace became the title of this exhibition, which grew out of connections and conversations with returned Volunteers in the Portland area. It was inspired by an aphorism of the late Oregon poet William Stafford, whose interest and commitment to peacemaking is well-known: “We put in a cottonwood post. It rooted and leafed.” The amazing image of the post rooting and leafing to new life captures the spirit of Peace Corps. That Volunteers are “posted” to serve in numerous places in the world is another understanding of the title. The title was also inspired by another Stafford aphorism: “Go in peace — but go.” Here are a few of the posters included in the exhibit.

This feature story in WorldView magazine also features stories behind some posters, the impact they had at the time, how they resonate decades later — and how they might be different if made today. Read contributions from:

Marieme Foote (Benin 2018–20) | Ken Hill (Turkey 1965–67), as well as agency Chief of Staff and Country Director for Macedonia, the Russian Far East, and Bulgaria | Anne Baker (Fiji 1985–87) | Janet Matts (Kenya 1977–79) | Wylie and Janet Greig (India 1966–68) | Joel Rubin (Costa Rica 1994–96) | Jon Keeton (Korea 1965–67), as well as agency director of international research and development, Regional Director for North Africa, Near East, Asia, and Pacific, and Country Director for Korea

“Peace Corps: A Promise…An Accomplishment…A Hope…1961–1981”

1981 poster, 17" x 22". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Usama Khalidi (Oman 1981–83)

“Think local. Act global.”

2003 poster 30" x 22". On loan from Stevenson Center for Economic and Community Development at Illinois State University

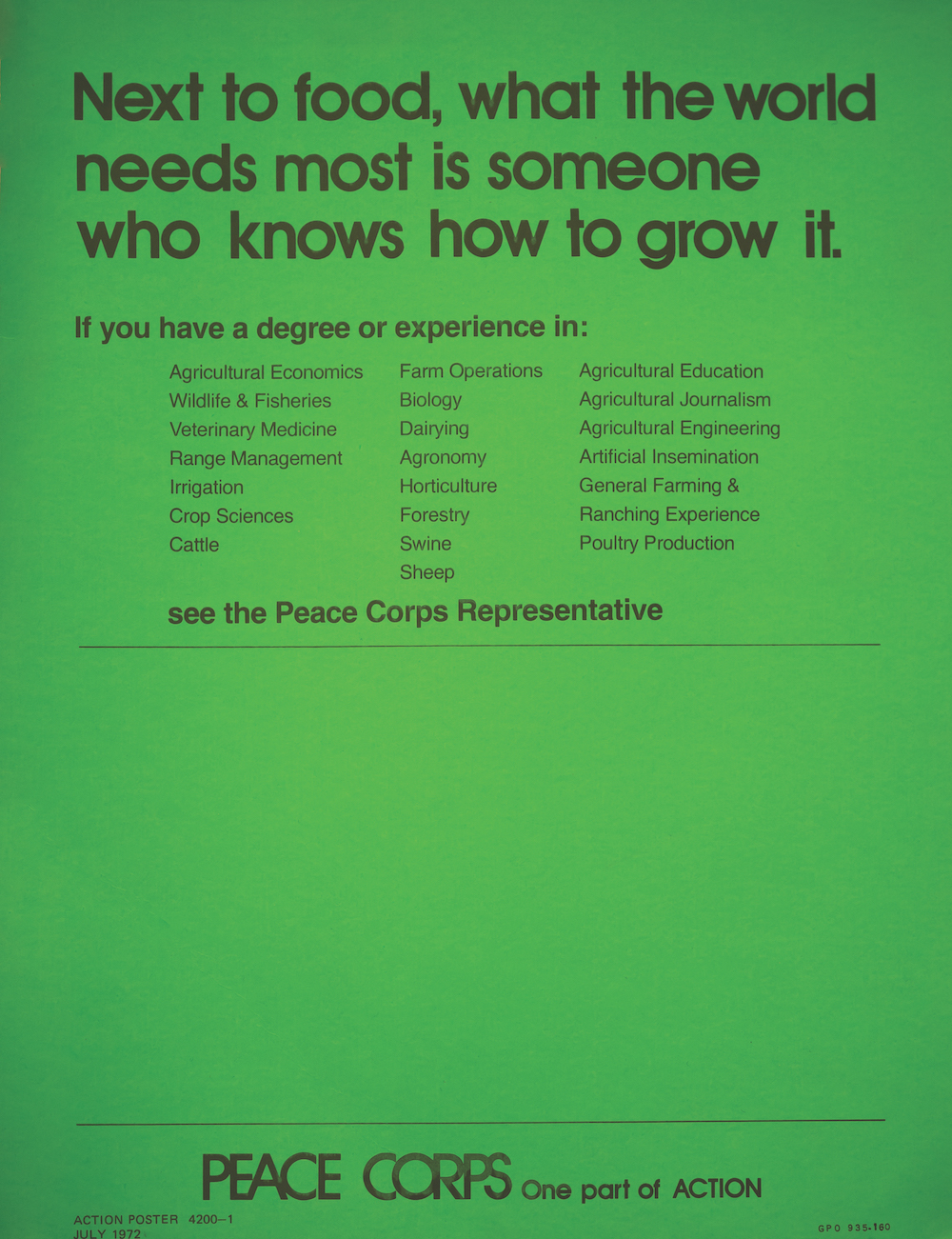

“Next to food, what the world needs most is someone who knows how to grow it.”

July 1972 poster, 11" x 8 ½". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Nancy Gallant (Malaysia 1969–71)

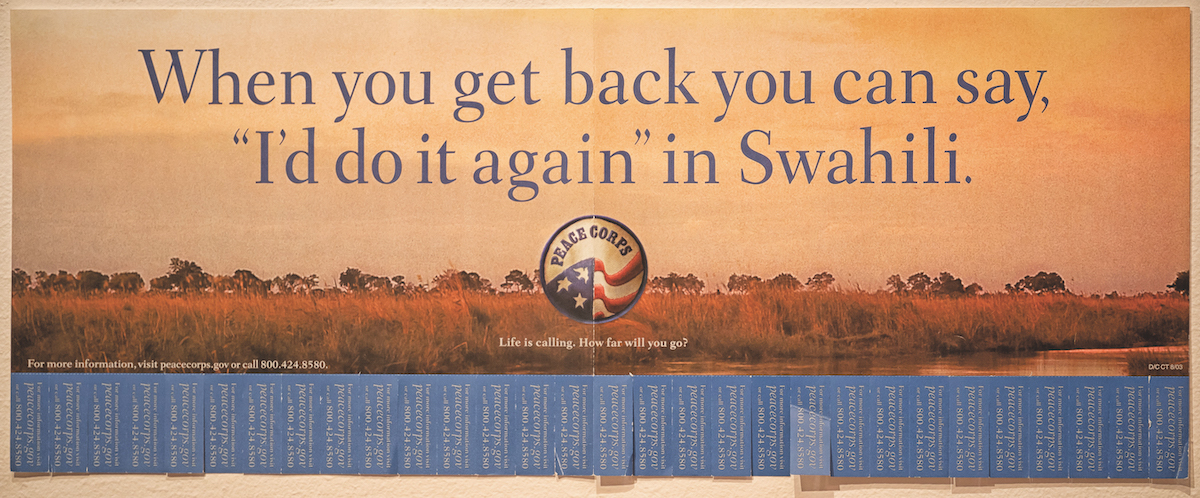

“When you get back you can say, ‘I’d do it again’ in Swahili. Life is calling. How far will you go?”

2003 poster, 8 ¾" x 21 ¾". On loan from Stevenson Center for Economic and Community Development at Illinois State University

“Here’s your wake up call.”

2003 poster, 30" x 22". On loan from Stevenson Center for Economic and Community Development at Illinois State University

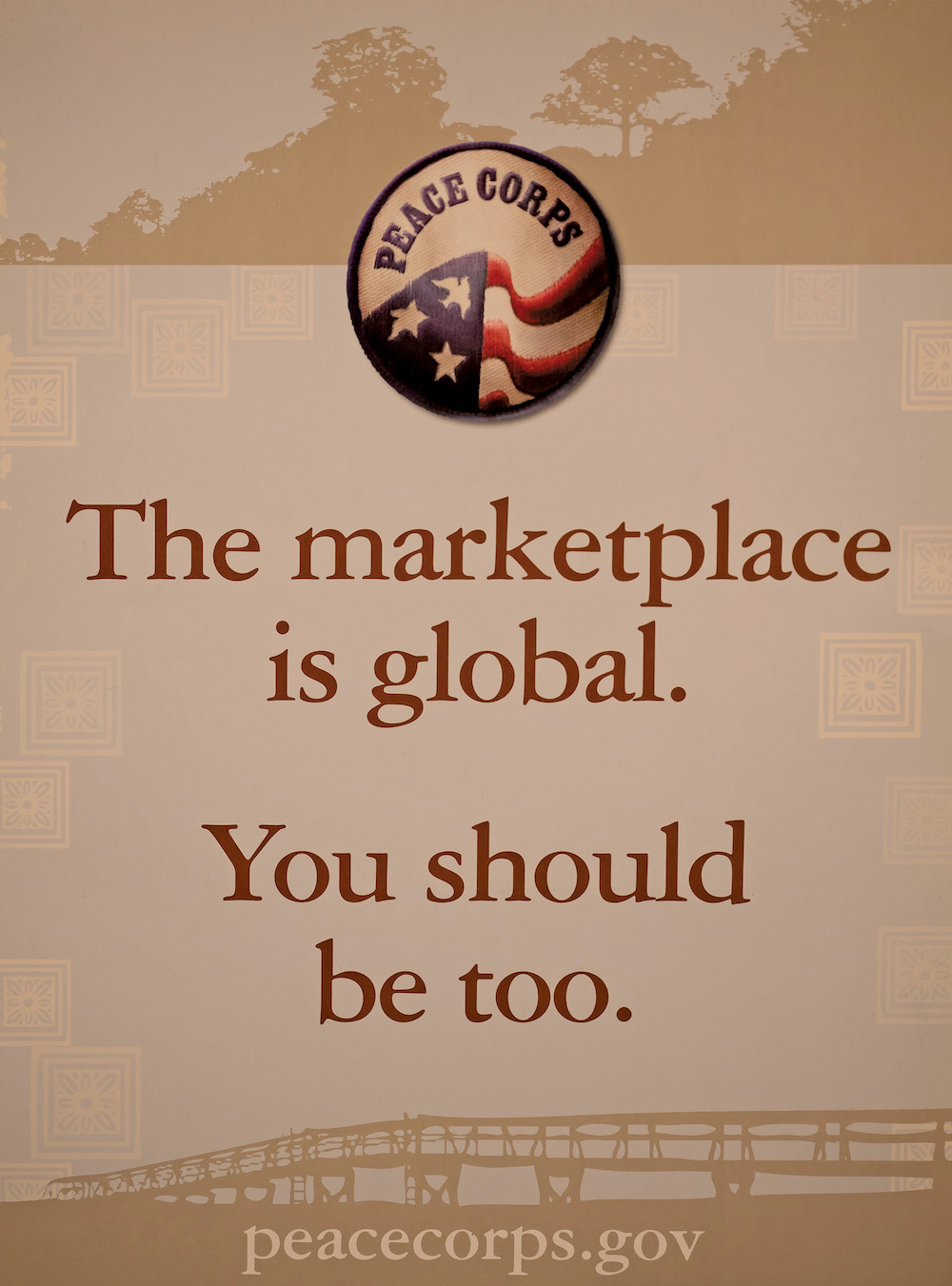

“The marketplace is global. You should be too.”

Undated poster 14" x 8 ¾". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Stevenson Center for Economic and Community Development at Illinois State University

The marketplace is global. You should be too. Opening up my perspective to a world beyond just the borders I live within or the countries I claim has helped me realize just how small I am, and just how beautiful the experience is to humble yourself to the world. The Peace Corps has been a step for me in bridging these connections and expanding my conception of a global world beyond just the capitals of major countries, but into the heart of people from all walks of life.

—Marieme Foote (Benin 2018–20) is a Donald M. Payne International Development Fellow at USAID and part of the advocacy team at NPCA.

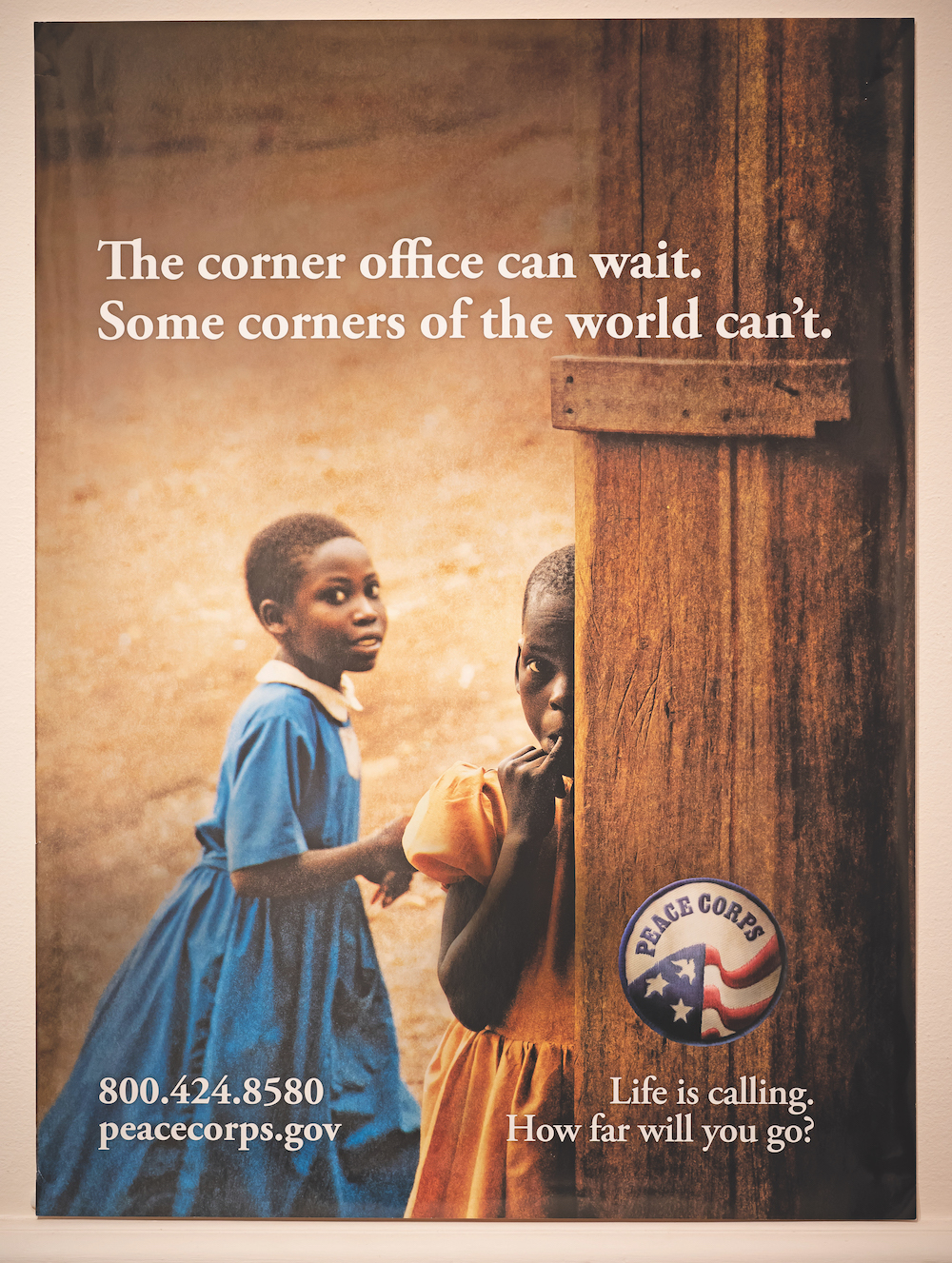

“The corner office can wait. Some corners of the world can’t. Life is calling. How far will you go?”

2003 poster, 30" x 22". On loan from Stevenson Center for Economic and Community Development at Illinois State University

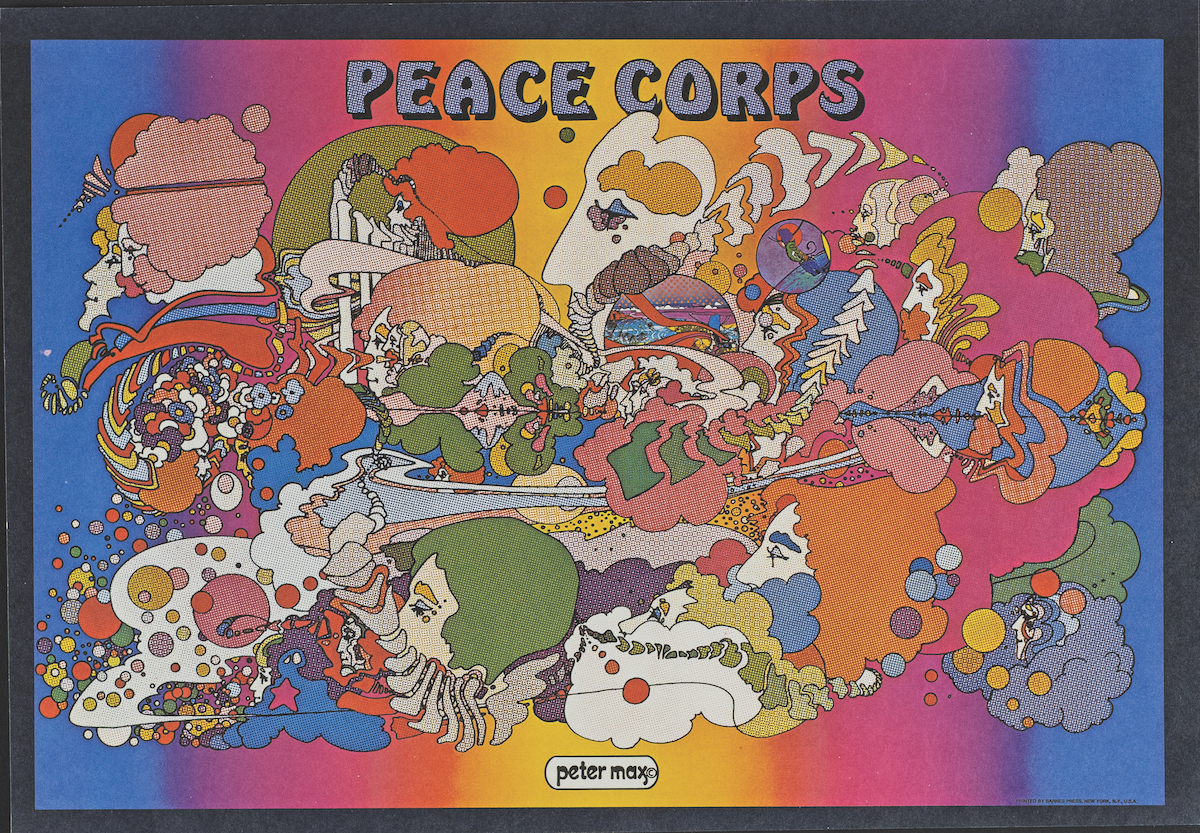

“Peace Corps.” 1971 design by Peter Max

Reproduction poster 11" x 16" printed by Barnes Press, New York. Original 21" x 26". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience

Recruiting on college campuses, I recall we had three versions of the posters with this Peter Max design. One was on poster paper with space at the bottom to note Peace Corps–related meetings, the location of the PC recruiting booth, classes that we were to speak to, etc. These disappeared almost as soon as we put them up, because the Peter Max painting was golden! A larger size simply advertised Peace Corps. It had a tendency to end up quickly in dorm rooms. Then there was the huge version, about four feet by six feet. These we only used in sealed displays or positioning that eluded pilfer. They were iconic, indeed.

—Ken Hill (Turkey 1965–67) served as Country Director for Macedonia (1966–67), the Russian Far East (1994–96), and Bulgaria (1996–99). He also served with Peace Corps HQ (1968–74), as chief of staff for the agency (2001), and as NPCA Board chair.

“Help Peace the World Together: Peace Corps.” 1972 anonymous design

Poster printed e-file, 15" x 11 1/2". Peace Corps Partnership Program. Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by National Archive and Records Administration

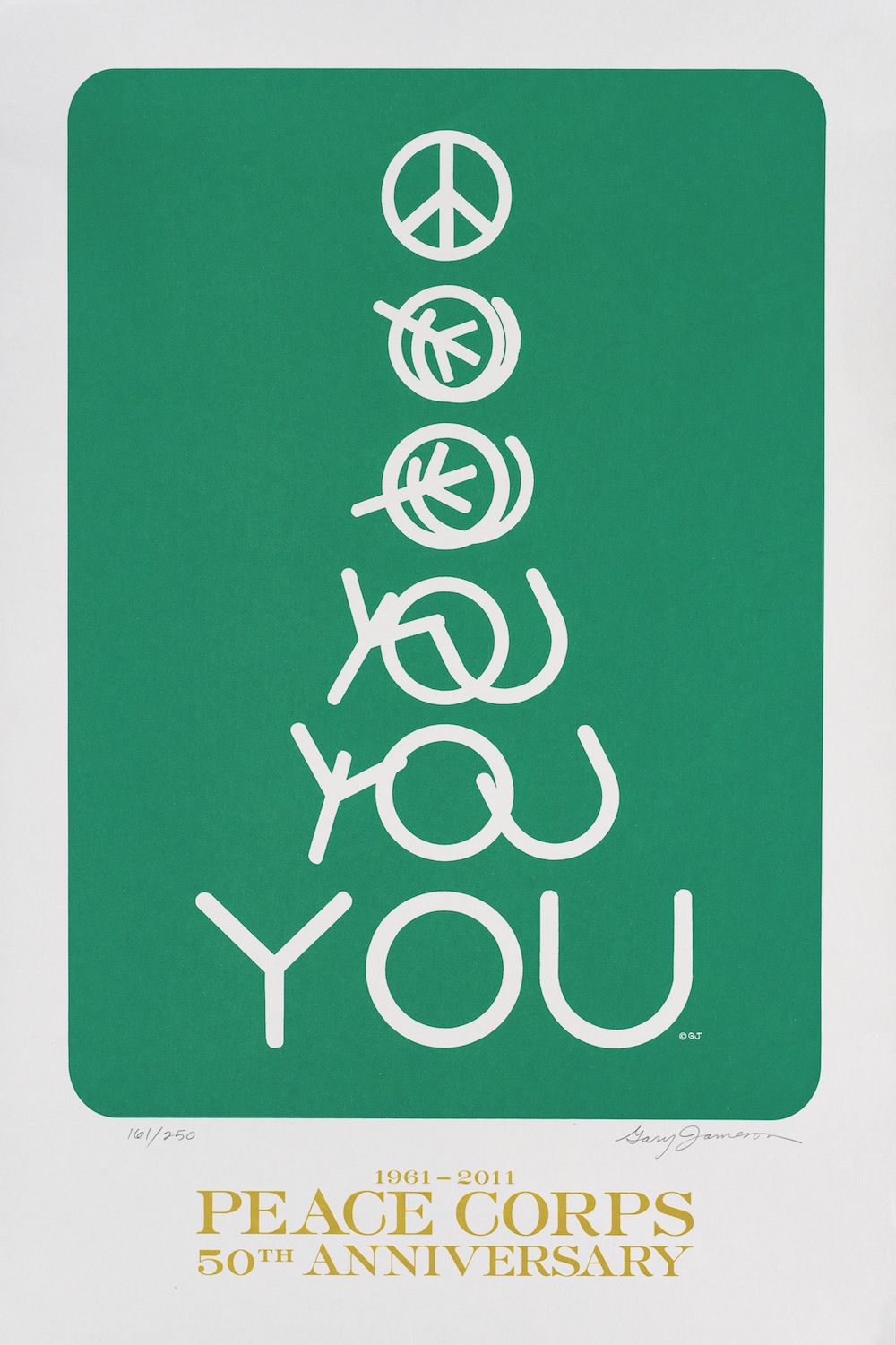

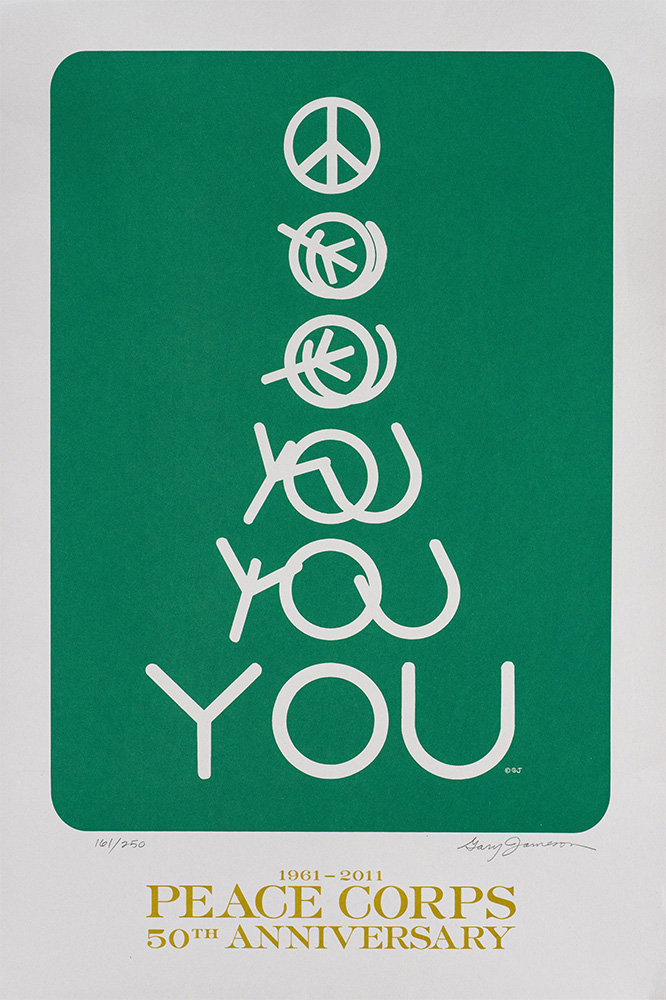

“You.” 2011 Peace Corps: 50th Anniversary 1961–2011. Designed by Gary Jameson

Screenprint 161/250, 18" x 12". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Anne Baker (Fiji 1985–87)

The YOU poster was one of three that RPCV Gary Jameson (Turkey 1965–67) designed for Peace Corps recruitment in the 1960s, and was one selected to commemorate Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary in 2011. This signed, limited edition print shows the evolution in five steps of the peace sign into the word YOU. That’s true if you start at the top. I take a different perspective, moving up the poster instead of down: The letters in the word YOU come together in just the right way to form the peace sign. That’s what we must do — working individually and collectively — to lift up our communities and our world to be at peace. This poster reminds us that YOU are the hope for that peaceful world.

This poster was designed to encourage Americans to join Peace Corps. But I think it sends just as powerful a message to Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, asking: What can YOU do to continue to build a more peaceful and prosperous world?

—Anne Baker (Fiji 1985–87) worked with National Peace Corps Association for a quarter century, most recently as vice president.

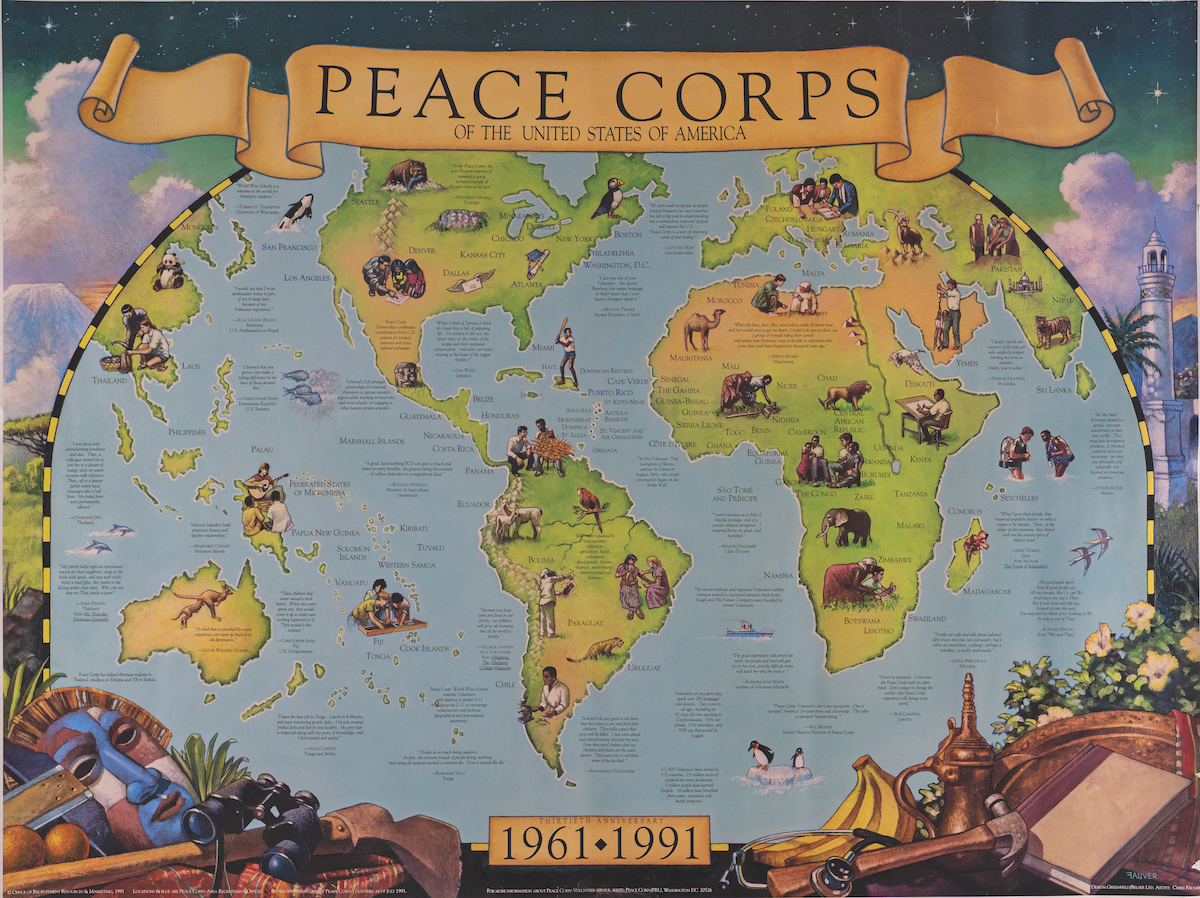

“Peace Corps of the United States of America 1961–1991.” 1991 30th Anniversary Map

Office of Recruitment Resources and Marketing poster, 27" x 36". Design: Chris Fauver of Greenfield/Belsar Ltd. Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Janet Matts (Kenya 1977–79)

I was lucky to be one of three Volunteers asked to start the first school for children with special needs in Westlands, near Nairobi, Kenya. That is my place on the map — Treeside Special School, funded by Mr. Menya, a Kenyan businessman whose disabled daughter was turned away from the government schools. However, Harambee (“Let’s all pull together,” in Swahili) served as a model for creating more schools throughout Kenya. A small Anglican church opened its doors to be used during the week as the school. Harambee also provided the impetus for many children with disabilities in Kenya, previously hidden at home, to attend school.

As we developed curriculum and planned daily programs, we identified individual disabilities — such as speech impediments — and prescribed special support. I quickly realized that the older children needed life skills — such as routine cooking and finding their way around the community. I brought students to my home twice weekly, taught them how to measure ingredients, read community signs, count bus fares, or read books. They enjoyed many Kenyan animal stories; our experiential approach to reading was based on Swahili writing, which — unlike English — uses easily pronounced phonetic words when written.

Treeside School became a model in Kenya. We trained a local teacher assistant to develop methods for teachers whose classroom experiences were limited. I will always appreciate the opportunity to make a contribution to Special Education in Kenya. This country taught me to value the Harambee spirit, and it has shaped my life ever since. So if I were to make this map myself, instead of a quote at the top from English historian Arnold Toynbee, it would be “Harambee. Let’s all pull together.”

—Janet Matts (Kenya 1977–79)

“Peace Corps.” March 1, 2011. Designed by Shepard Fairey. 50th Anniversary Commemorative Print

Screen print on French Cream Speckletone paper, 2/450, 24" x 18". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Wylie and Janet Greig (India 1966–68)

In 2010, the NPCA Board and the agency were beginning to plan for ways to celebrate the upcoming 50th anniversary of Peace Corps. Janet had joined the NPCA Board and was beginning the work of raising funds to support proposals for celebrating this milestone in its history.

Out of the blue, we received a call from Peace Corps headquarters asking if we would visit with one of the Director’s representatives, who was to be in California the following week. She arrived with a specific ask in mind: Would we be willing to fund a commemorative poster which was being commissioned by the artist Shepard Fairey? We knew of Fairey’s work — both as a commercial artist and the creator of Barack Obama’s iconic poster for his recent presidential campaign.

We were intrigued by the image — a U.S. Volunteer kneeling in concert with a young man. They are observing a plant sprouting in her hands — was it simply a reference to agricultural Volunteers? Or could it represent progress for them both? Or hope? Or mutual coming together in support of something bigger than either

of them? Learning from one another?We think all of these. Our lives were greatly changed and enriched by our time as Peace Corps Volunteers in India working alongside Indian partners.

—Wylie and Janet Greig (India 1966–68)

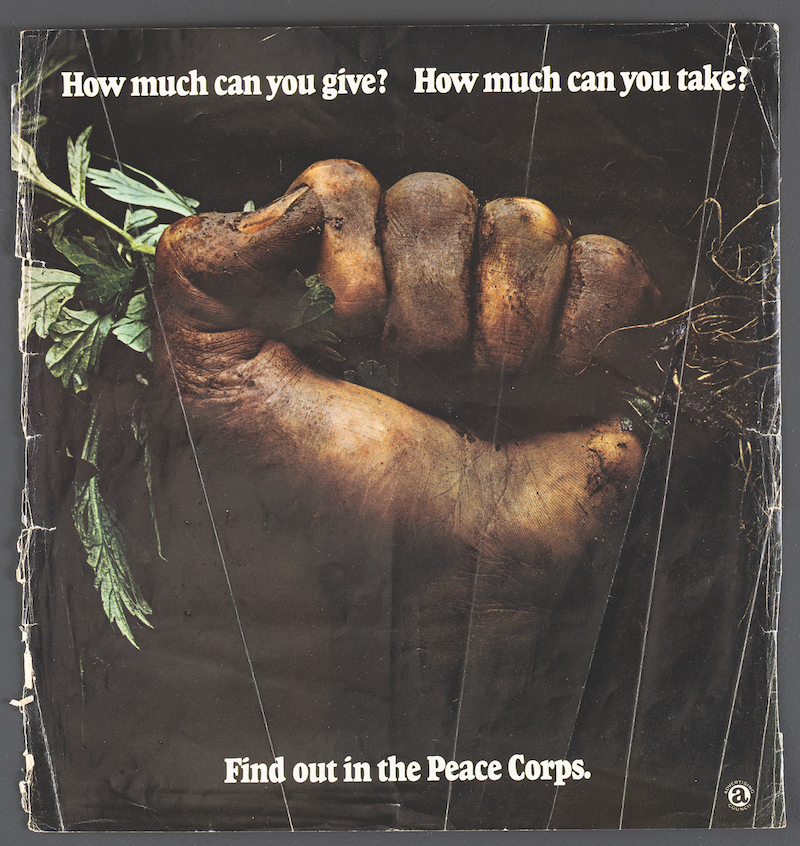

“How much can you give? How much can you take? Find out in the Peace Corps.”

c.1965 poster, 11" x 10 1/2". Advertising Council. Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Ethel Fleming (Micronesia 1966–68)

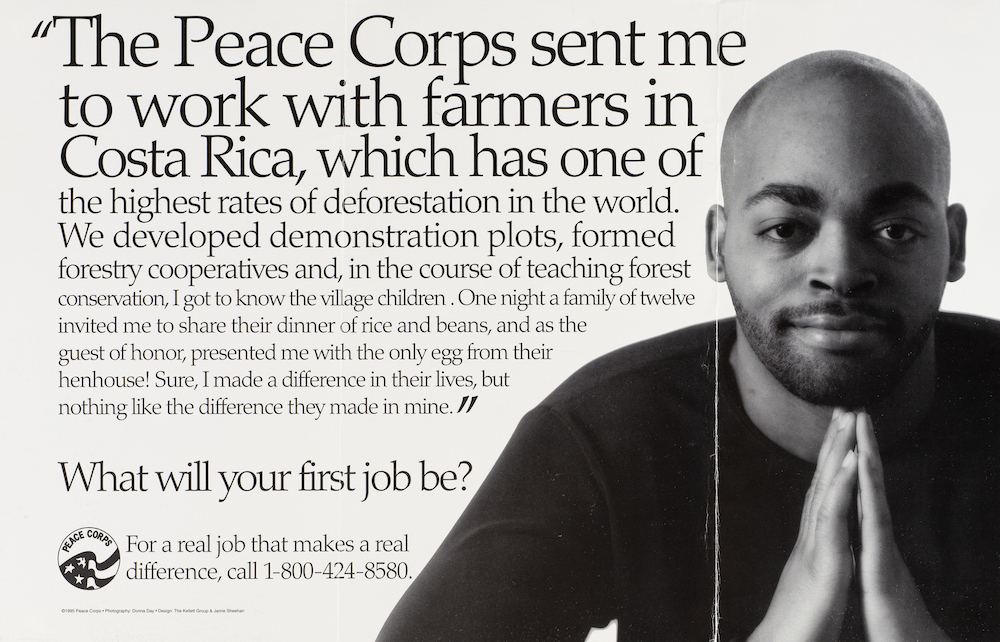

“The Peace Corps sent me to work with farmers in Costa Rica…”

1995 photograph by Donna Day, Kellet Group & Jamie Sheehan, 11" x 17". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by Doug Newlin (El Salvador 1965–67, Papua New Guinea 2000) and Sheila Newlin (Papua New Guinea 2000)

Costa Rica is a small, peaceful country in the heart of Central America, where the citizens could teach the world more about peace than we ever could for them. This country — rich in biodiversity, with a full quarter of its land protected as national parks — has no military. Instead of spending countless colones to defend its borders with oversized militaries like many of its neighbors, it spends its funds on public health, education, and social services. The result? A life expectancy of 80 years, higher than the United States. Yet as we know, peace is rooted in partnership. As a Peace Corps Volunteer serving there in the mid-1990s, I found that partnership is exactly what Costa Ricans wanted. It was their strong sense of national pride, combined with the confidence to demand to be treated as equals that made — and makes — Costa Rica a dynamic partner for the United States. And for me, Costa Rica and its people are family, equals, partners, and compadres in the struggle to make the world a safer, more environmentally sustainable, and peaceful place for us all.

—Joel Rubin (Costa Rica 1994–96) served in the Obama-Biden Administration as the deputy assistant secretary of state for legislative affairs and recently as NPCA’s vice president for global policy and public affairs.

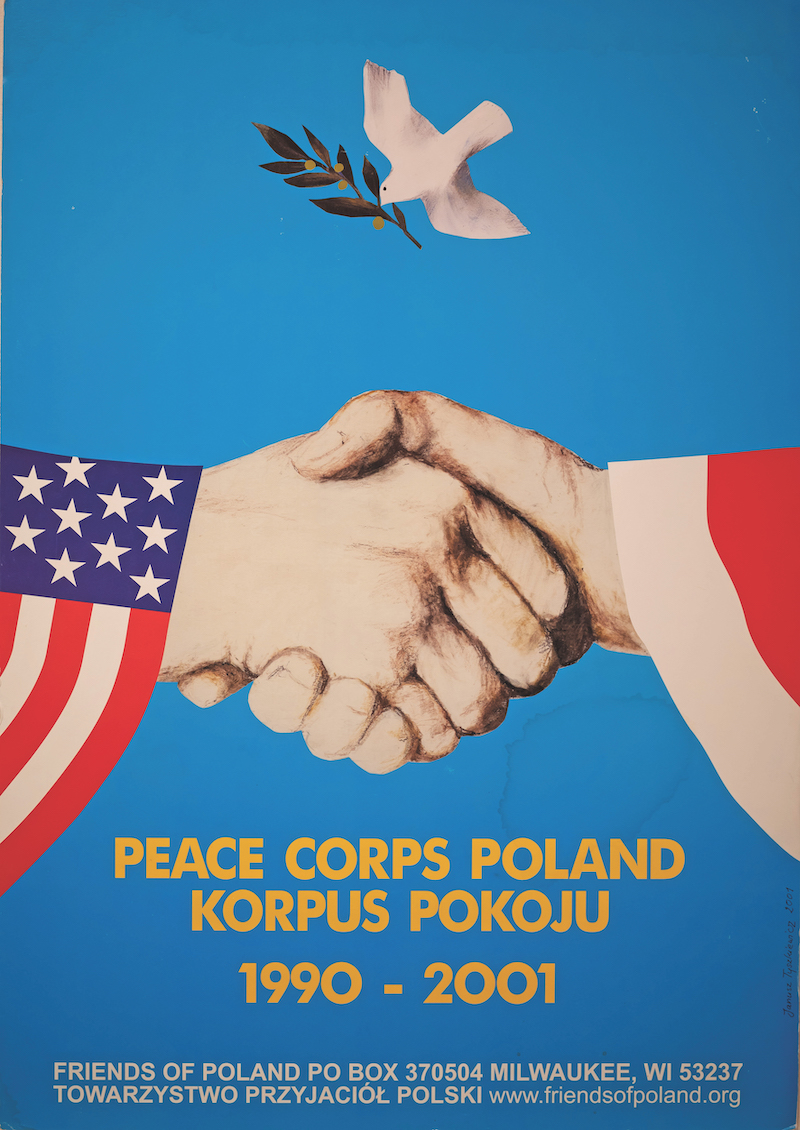

“Peace Corps Poland, Friends of Poland, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2001.”

Designed by Janusz Tyszluèwicz. Poster, 27" x 19". Museum of the Peace Corps Experience. Donated by John Keeton (Thailand 1965–67, Peace Corps staff 1970–76, 1984–92)

The message of the Peace Corps Poland poster — partnership — is even more relevant now than when it was given to me by a Ukrainian American Volunteer two decades ago. He was so pleased that he could serve in his family’s homeland. When I had the honor to negotiate the country agreement I never dreamed how long Volunteers would serve there.

—Jon Keeton (Korea 1965–67) served as Country Director for Korea (1973–76) and Regional Director for North Africa, Near East, Asia, and Pacific (1984–89), and as Peace Corps’ director of international research and development.

This feature appears in the Winter 2023 edition of WorldView.

SEE MORE from this exhibit at: https://museumofthepeacecorpsexperience.org

-

Steven Saum posted an articleCelebrating Where Peace Corps Training Began see more

Celebrating Where Peace Corps Training Began

By Tiffany James

Photo at left: Students in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) with Roger Rhatton, a Peace Corps Volunteer from Bay Village, Ohio, 1965. Photo courtesy National Archives

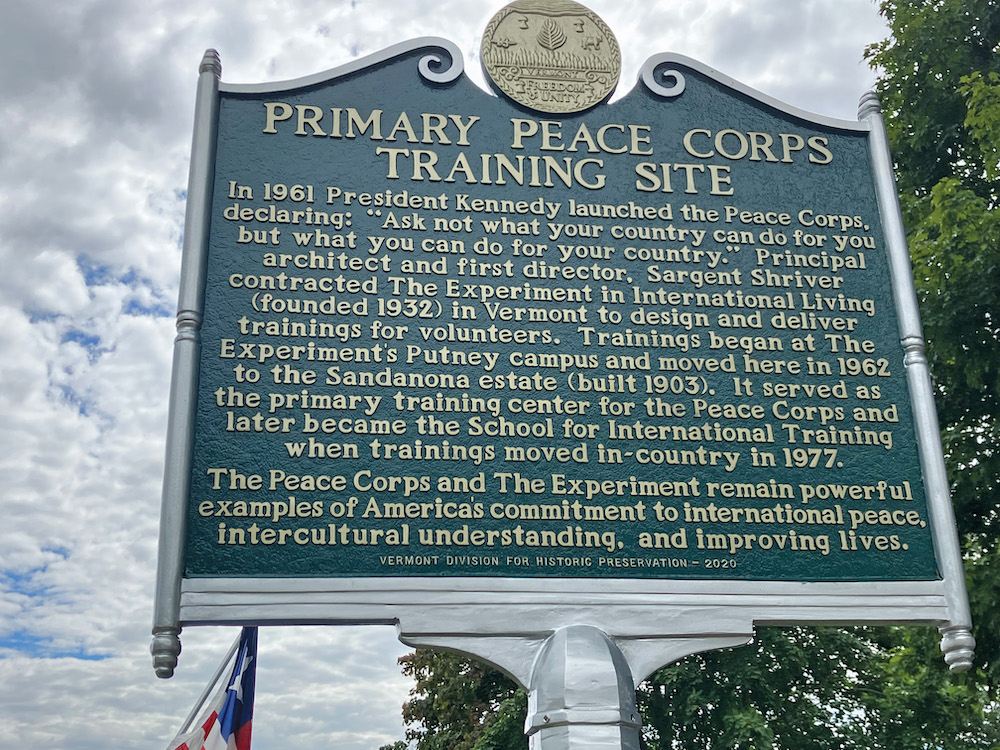

In the early years of the Peace Corps, many of the first Volunteers began training on a campus in Brattleboro, Vermont, which is home to the School for International Training. Now there’s a marker honoring that legacy — and the roots of the Peace Corps in the Experiment in International Living.

Sargent Shriver, the first director of the Peace Corps, was himself a participant in the Experiment in International Living before World War II. With the launch of the Peace Corps, he reached out to Experiment leaders to assist with training Volunteers headed to Gabon and Pakistan. And a decades-long partnership was born.

These Peace Corps training activities led to the establishment of the academic institution now known as SIT, which has educated countless members of the Peace Corps community over the years, offering undergraduate study abroad and master’s degrees in global issues. On August 13, members of the Peace Corps community, politicians, and university leadership came together for a ceremony dedicating a historical marker that honors “examples of America’s commitment to international peace, intercultural understanding, and improving lives.”

Sign of the Times: paying tribute to the people and place. Photo courtesy Peace Corps

Among the presenters at the ceremony were keynote speaker Carol Spahn, CEO of Peace Corps; Sophia Howlett, president of SIT; Carol Jenkins, CEO of World Learning, the parent organization of SIT; and Congressman Peter Welch (D-VT). Javonni McGlaurin, who studied at SIT and served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines 2014–16, read a letter from Tim Shriver, who leads the Special Olympics board of directors and is the son of Sargent Shriver. A letter from Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) was read by staff member Katherine Long. NPCA Interim President and CEO Dan Baker participated in the dedication ceremony as well.

In true Peace Corps fashion, grassroots efforts helped make this moment: It was a group of returned Volunteers in Vermont who advocated for the creation of this permanent historic marker. Carol Spahn, who earlier in the day delivered the commencement address for SIT, thanked the returned Volunteers in her keynote address. “It’s important to recognize those moments that bring us to where we are and to really honor the intention with which we come together today and with which our organizations were formed,” Spahn said.

“No alliance of organizations or people have done more to break down the walls of misunderstanding and fear that have divided culture from culture, religion from religion, country from country, people from people.”

—Tim ShriverIn his letter, Tim Shriver paid tribute to the partnership being celebrated. “No alliance of organizations or people have done more to break down the walls of misunderstanding and fear that have divided culture from culture, religion from religion, country from country, people from people,” he wrote.

This story appears in the Winter 2023 edition of WorldView magazine.

-

Orrin Luc posted an article“My choice to join the Peace Corps changed everything,” Williams writes. see more

A Life Unimagined: The Rewards of Mission-Driven Service in the Peace Corps and Beyond

By Aaron S. Williams

International Division, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Aaron S. Williams grew up in a segregated neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side in the 1950s. When he began studying geography at Chicago Teachers College, it was because the subject would offer him good career opportunities in the public schools. But, as he notes early in the memoir A Life Unimagined, “studying the geography of distant places around the world…the seeds once planted by my father of distant travels began to take root.” That’s not to say his father encouraged him to join the Peace Corps; he didn’t. But his mother and his best friend both did.

“My choice to join the Peace Corps changed everything,” Williams writes. For his mother, too; she would visit him when he was a Volunteer in the Dominican Republic, and over his two decades as a foreign service officer with USAID in Honduras, Haiti, Barbados, and Costa Rica. It was only because of failing health in her older age that she didn’t visit her son and his family in South Africa, where Williams was stationed not long after the end of apartheid. The day after he arrived to begin leading the USAID mission, Williams met President Nelson Mandela.

Rewind for a moment: After serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer 1967–70, Williams took on responsibilities for the agency coordinating minority recruitment. He earned an MBA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then went to work in the corporate world, learning the ropes in the food industry. That set him on track for work in U.S. government-supported agribusiness development in Central America.

The capstone of his career in public service came in 2009, when Williams was appointed by President Barack Obama to serve as Director of the Peace Corps—the first African-American

man to hold the post. During Williams’ tenure, the Peace Corps marked its 50th anniversary, with celebrations around the world. The agency also secured a historic budget increase and reopened programs in Colombia, Sierra Leone, Indonesia, Nepal, and — in the wake of the Arab Spring — Tunisia. In terms of program successes, Williams points to new and expanded initiatives in Africa to address hunger, malaria, and HIV/AIDS — through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the President’s Malaria Initiative, Feed the Future Initiative, and Saving Mothers, Giving Life.Aaron Williams with Senator Harris Wofford at his confirmation hearing in 2009. Wofford was a friend and mentor to Williams, and he introduced Williams that day.

Photo Courtesy of Aaron S. WilliamsIn terms of challenges, the year 2011 brought intense scrutiny to the agency following an investigation by the ABC news program “20/20” examining how six women serving as Volunteers had been victims of sexual assault. The program also looked at the tragic murder of Volunteer Kate Puzey, after she reported that a teacher at her site in Benin was sexually abusing students. Puzey’s death occurred some months before Williams became director, but the serious questions her murder raised about safety, security, and confidentiality still needed to be addressed. Williams worked with Congress to institute reforms, such as heightened security, and training and support for victims, that led to the passage of the Kate Puzey Peace Corps Volunteer Protection Act, signed by President Obama in November 2011.

Before his Peace Corps leadership role, Williams served as vice president of international business development for RTI International. In 2012, after stepping down from the directing the Peace Corps, he returned to RTI as executive vice president the International Development Group and now serves as senior advisor emeritus with the organization.

In his public writing in recent years, Williams has called on U.S. foreign affairs agencies to rise to demonstrate leadership in pursuing policies and programs that will improve diversity in their ranks by investing in the diverse human capital of our nation, to reflect the true face of America. And, not surprising, he has been a strong advocate for public service here in the U.S. Indeed, the foreword for his memoir—contributed by Helene Gayle, who formerly led the Chicago Community Trust and now is president of Spelman College, makes the case for that: “I hope that the life and career of Aaron Williams, as portrayed in this book, will inspire future generations of underrepresented groups in our society, both men and women, who seek to make a difference by serving America and the world at large.”

Celebrating Fifty Years

AN EXCERPT FROM A LIFE UNIMAGINED BY AARON S. WILLIAMS

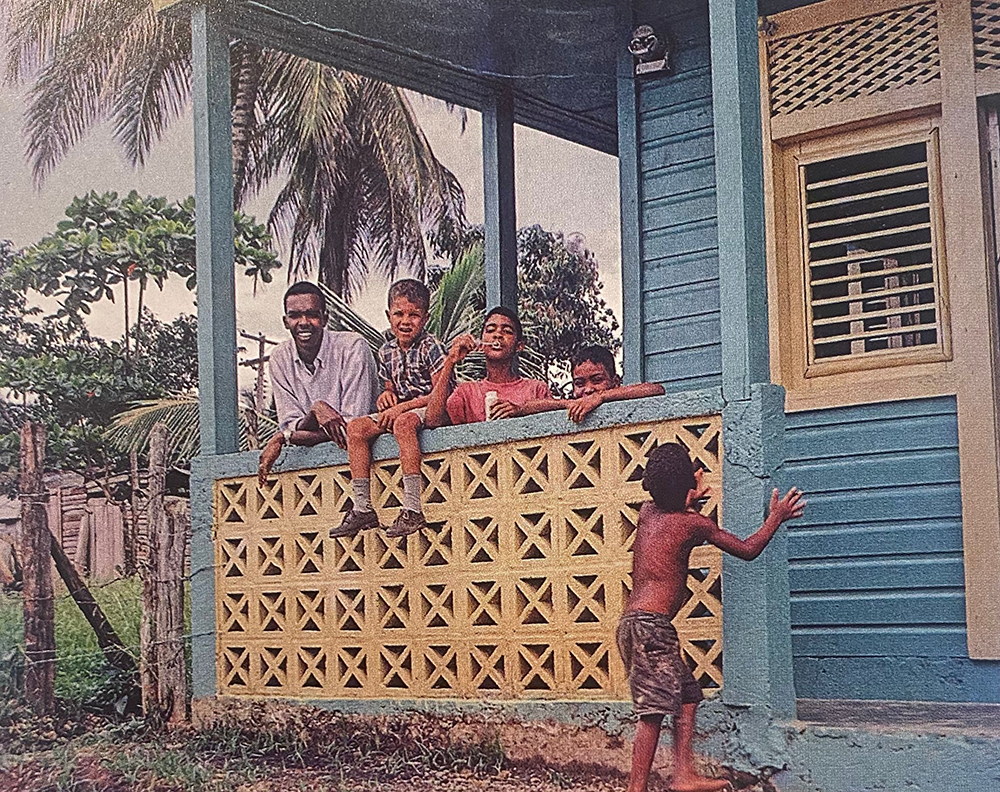

The American Airlines Boeing 727 began its descent from our flight that began in Miami, passing at a low altitude over the beauty of lush, emerald-green mountains, aquamarine-colored ocean, and long white beaches. Eventually the sprawling city of Santo Domingo appeared, separated by the Ozama River as it coursed its way into the Caribbean. This country held special memories for Rosa and me—it was my second home and where she was born. We gazed over the country’s natural beauty during another landing in the modern Airport of the Americas, a trip we’d made so many times since 1969. This arrival felt very different from my first at the old airport in December 1967 when I was a newly minted PCV.

This return to my beginnings in the Peace Corps highlighted for me the incredible journey that began as a college graduate’s surprising path to adventure. Here, I met my beautiful wife, seated beside me as we returned “home,” back to where my life was transformed. We were going to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the warm, friendly relationship created between this nation and the Peace Corps Volunteers who had served here throughout its rich history. That unique, historical bond, forged in the white heat of the Dominican revolution and the U.S. invasion in 1965, had brought about this seminal moment. During that time of strife and struggle, many of the PCVs of that era gained the respect of Dominican citizens by vigorously supporting the country’s revolutionaries and not following the Johnson administration’s official policy during a crucial period in Dominican history.

This return to my beginnings in the Peace Corps highlighted for me the incredible journey that began as a college graduate’s surprising path to adventure.

On this trip, Rosa and I would be participating in a series of events to celebrate, commemorate, and treasure the more than 500 participants who had worked side by side with the Dominican people in the spirit of friendship and peace. Current and former Volunteers and staff would reunite at a three-day conference and share in the success of 50 years of Peace Corps work in the Dominican Republic. This auspicious anniversary also presented us with the chance to engage with Peace Corps Volunteers and staff worldwide and observe the scope and impact of the organization’s 50-year global engagement. I experienced firsthand the warm reception that Peace Corps Volunteers continue to receive worldwide.

Our gracious hosts for these anniversary events were Raul Yzaguirre, U.S. ambassador to the Dominican Republic, and country director Art Flanagan. Yzaguirre is an icon in the Hispanic American community and a civil rights activist. He served as the president of the National Council of La Raza from 1974 to 2004 and transformed the organization from a regional advocacy group into a potent national voice for Hispanic communities.

Many returned PCVs made site visits to the towns and villages where they had lived and worked, often hosted by the current PCVs; such a site visit was nostalgic for the former Volunteer and also an exciting historical experience for the local citizens. Rosa and I were very happy to enjoy once again the company of so many friends who shared this collective experience, especially Dave and Anita Kaufmann, Bill and Paula Miller, and Dan and Alicia Mizroch. The men all served as PCVs in the late 1960s, so the celebration also

represented a special homecoming between lifelong friends! Further, we had a joyful reunion with Judy Johnson-Thoms and Victoria Taylor, the PCVs with whom I had served in Monte Plata.Monte Playa: As a Volunteer in the Dominican Republic, Aaron Williams, left, with his neighborhood buddies and informal language teachers. Photo Courtesy of Aaron S. Williams

Dominican officials, our former counterparts, and many Dominican friends hosted events for Peace Corps participants in the grand style of a “family” reunion. Major Dominican newspapers and broadcast media provided extensive coverage of the celebration. Like many returned PCVs, I had the great pleasure of holding a mini-reunion with my former colleagues from the University Madre y Maestra, many of whom I had not seen since 1970!

We all felt honored to be joined by a special guest, Senator Chris Dodd, a proud returned PCV who served when I did in the Dominican Republic. During his five terms in the U.S. Senate, Chris had always been a great champion of the Peace Corps. For many years, he served as the chairman of the subcommittee responsible for oversight of the Peace Corps. Because he had presided over my confirmation hearing, it was especially gratifying to participate in this homecoming with him.

The planning for the Peace Corps’ 50th-anniversary celebrations, both in the United States and overseas, had begun before my appointment, under the previous director Ron Tschetter. Of course, we were enthusiastic about building upon these efforts. We were determined to hold a worldwide celebration that would highlight this significant landmark in the agency’s history and celebrate the legacy of this American success story — it would be a celebration to remember!

I have often reflected on the warm relationships between the Peace Corps and our host countries. The relationships that PCVs fostered for 50 years were indicative of the power of the organization in pursuing its mission of world peace and friendship. The outpouring of admiration, affection, and respect was something to behold as we continued preparing for these global celebrations. In each location, the country director and their staff created scheduled events representing the Peace Corps’ past and present role in each country, resulting in rich and diverse programs.

Those of us at headquarters planned several special events in Washington, D.C., to highlight and honor the Peace Corps legends who had been Sargent Shriver’s colleagues and to welcome the returned PCVs and other staff community back home. At the same time, returned PCV affinity groups — such as Friends of Kenya, Friends of Paraguay, and so forth—held anniversary activities in every state and in scores of colleges and universities across the United States. The national celebration aimed to demonstrate the organization’s continuing role in American life and history.

Overall, our senior staff traveled to 15 countries, 20 states, and 28 cities to celebrate the 50th anniversary. The Peace Corps senior staff worked to ensure broad representation; Carrie Hessler-Radelet, Stacy Rhodes, and I carefully planned our calendars to maximize our participation in major events in each region of the world and across the United States.

Our trips to visit the Volunteers in the host countries were a great privilege, and in my visits I stressed the importance of the individual and collective service of our PCVs and my personal connection with the work of the modern PCV. What a sight it was to see Volunteers on the front lines, working in microbusiness-support organizations to create new women-owned small businesses, teaching math and science in rural primary schools, or distributing mosquito nets in remote villages to fight malaria under our Stomp Out Malaria program, working in HIV/AIDS clinics, or helping small farmers improve irrigation systems.

The variety of PCV assignments was truly spectacular, from leading young girl empowerment clubs in rural Jordan, to coaching junior achievement classes in Nicaragua, teaching math in rural Tanzania, teaching internet technology in high schools in the Dominican Republic, teaching English as a second language in a girls’ school in rural Thailand, working on improved environmental protection practices in Filipino fishing villages, and helping to advise on improved livestock breeding techniques on farms in Ghana. Though I had once been in similar circumstances as a young PCV, I couldn’t help but be impressed by what I saw.

My colleagues and I had the pleasure of participating in several country celebrations during the 50th anniversary year, and it typically involved the following scenario. Of course, a meeting with the president of the host country and/or another senior government official would be first on the list for a country anniversary celebration. Many of these leaders had worked with or had been taught by Peace Corps Volunteers over decades. We also met with the leaders of the vital counterpart organizations, including community groups, government ministries, and the leading nongovernmental organizations in the country. We visited Volunteers at their worksites to observe their activities and attended a dinner or reception hosted by the U.S. ambassador for the PCVs, local dignitaries, and guests.

Another important aspect of my country visits was broad engagement with the national print, radio, and television press through press conferences, individual interviews, or both. In almost every case, returned PCVs who had served in a particular country participated in the events, often in coordination with the returned PCV affinity groups (e.g., in the case of Tanzania, Paraguay, Kenya, or Thailand), along with current PCVs and their guests. A typical visit for an anniversary event would run two days, and Carrie, Stacy, or I attended as the senior Peace Corps representative for a particular celebration.

Ghana is one of the most prominent nations in West Africa, and Sargent Shriver established the first Peace Corps program there in 1961. Its first president was the famous Kwame Nkrumah, who led the country to independence from Great Britain. Known during the colonial era as the Gold Coast, Ghana was also the location of some of the principal slave-trading forts in West Africa. Stacy Rhodes, Jeff West, and I traveled together to Ghana, where we spent three days in a series of events to celebrate the 50th anniversary in this historic Peace Corps country.

After our first day of courtesy meetings with government officials, local counterpart organizations, Volunteers, and staff, we decided to visit a famous fort. It was a heart-wrenching experience for Stacy and me, brothers in service, to stand before the fortress, built as a trading post with slaves as the primary commodity. We could only look out on the vast Atlantic Ocean through the “door of no return” in the bottom of that castle with sadness, knowing that those poor souls had been ripped from their native land. We felt it was necessary to witness the dungeons where they were held captive and the path they were forced to walk as they boarded the ships in the harbor that would take them to the West Indies or the American colonies, separating them forever from their homeland.

These are experiences not easily comprehended from afar, but they represent a crucial part of the human story that needs to be retold and remembered. Ideally, they set the stage for improving the human condition in the future.

One of the highlights of the trip was our participation in the country’s annual teacher day. I joined the vice president of Ghana, John Mahama, for this special event in an upcountry district capital. Stacy, the country director, Mike Koffman, and I were driven two hours from the capital city of Accra to the district capital. Mike had had a tremendous public service career, first as a Marine Corps officer, then as a founder of a nonprofit organization that provided legal services to the homeless in Boston, and then as an assistant district attorney in Massachusetts. After his stint as assistant district attorney, he served as a PCV in the Pacific region, and now we were fortunate to have him as our Ghana country director.

In Ghana, the top teachers were selected each year for special recognition. One of the ten teachers chosen that year was a PCV whose parents were both returned PCVs who had served in Latin America. This national ceremony honors outstanding teachers for their exemplary leadership and work that affected and transformed the lives of the students in their care and the community around them. The overall best teacher receives Ghana’s Most Outstanding Teacher Award and a three-bedroom house. The first runner-up receives a four-by-four pickup truck, and the second runner-up receives a sedan; indeed, a very different approach from how we honor teachers in America. I looked forward to participating in this important ceremony, during which the vice president and I would deliver speeches.

When we arrived at the government house in the district capital, I planned to discuss with the vice president a few points regarding the future of the Peace Corps program in Ghana. However, Vice President Mahama, who subsequently was elected president of Ghana in 2012, was more interested in talking about his experience with a PCV during his youth, and I listened to what he had to say with great interest.

He described how, as a young boy, he had attended a small primary school in rural northern Ghana. There were 50 to 60 boys in a very crowded classroom with very few desks and textbooks. They heard one day that a white American was coming to teach them, and they were anxious about this. They had never seen a white man before in their village, and they didn’t even know if they would be able to understand his language.

When the young American PCV came into the classroom, he looked around the class and said that he was going to teach them science. He then asked them, “Do any of you know how far the sun is from the earth?” The boys all stared at the floor; they didn’t understand why he asked this question or why it was important, but either way, they didn’t know the answer.

That day, for future Vice President Mahama, was a turning point in his life when he saw the possibilities of another world. He also told us about several of his friends from his village school in that same class who had gone on to become scientists or engineers.

The PCV walked up to the front of the classroom, took out a piece of chalk, and wrote down on the blackboard the number ninety-three; he put a comma behind it and then proceeded to write zeros on the front blackboard until he quickly ran out of room, and then he continued to put zeros on the walls of that small room, returning to the ninety-three on the blackboard. Then he exclaimed, in a loud voice, “It’s ninety-three million miles from the earth! Don’t ever forget that!” That day, for future Vice President Mahama, was a turning point in his life when he saw the possibilities of another world. He also told us about several of his friends from his village school in that same class who had gone on to become scientists or engineers.

From the government house, we went on to the stadium to participate in the teacher day festivities. Marching bands and students from all around the area welcomed us and an audience of thousands on the impressive parade grounds of the city. The vice president and I shook hands with and gave the awards to each of the winners, and we had a chance to meet the young PCV who had been selected as one of the winners. It was a long but satisfying day, and I’ll always remember my visit to this historic Peace Corps country.

I have equally vivid memories of traveling to a small village in Ghana, where we visited a young PCV from Kansas, Derek Burke. As I recall, he grew up on a farm, and now, in this remote and arid region of the country, he worked with the local farmers on a tree planting project, helping them to plant thousands of acacia trees. As we slowly walked into the village, we were welcomed by the hypnotic sounds of ceremonial drumming and greeted by more than 200 villagers. I loved seeing the smiling children as we met the village elders and local government officials. We then held a town hall meeting under an enormous baobab tree — a tree large enough to provide shade for all assembled.

As we departed, I was asked to visit with the patriarch of the village, who hadn’t been able to join us due to his failing health. He lived in a small hut on the outskirts of the village. The PCV and I went to his bedside. I can still feel the firm grip of the frail-looking gentleman, who appeared to be in his late 80s. He held my hand as he thanked me through a translator for visiting his village and for the “gift” of the young American PCV whom everyone loved. As I drove away, I thought about the symbolic importance of sending one Volunteer to serve in a remote village in Ghana and how he walked in the steps of those who came 50 years before him, in service to the country and the building of friendship in the name of the United States.

On a spectacularly beautiful day in June 2011, our plane landed in Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, after a short stop in Arusha, near Mt. Kilimanjaro, where the majestic mountains loomed large from the airplane window. Esther Benjamin, Elisa Montoya, and Jeff West accompanied me. Dar es Salaam is a name that conjures up visions of Zanzibar and the ancient trading routes between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. This nation, formed by the union of Tanganyika (colonial name) and the island of Zanzibar, has some fifty-five million citizens and is 60 percent Christian and over 30 percent Muslim, with two official languages: Swahili and English.

Tanzania was led into historic independence by the legendary Julius Nyerere, known as the “father of the nation,” who campaigned for Tanganyikan independence from the British Empire.4 Influenced by the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, Nyerere preached nonviolent protest to achieve this aim. His administration pursued decolonization and the “Africanization” of the civil service while promoting unity between indigenous Africans and Asian and European minorities.

The outstanding country program was led by one of our most experienced country directors, Andrea Wojna-Diagne, who received strong support from Alfonso Lenhardt, the U.S. ambassador to Tanzania.

In Tanzania, we started our visit by meeting with President Kikwete and his senior officials. It was a pleasure to learn that the president, as a young elementary school student, had been taught by a Peace Corps Volunteer. He had a very positive view of the Peace Corps, and he recognized its importance to the relationship between the United States and his country.

We started our visit by meeting with President Kikwete and his senior officials. It was a pleasure to learn that the president, as a young elementary school student, had been taught by a Peace Corps volunteer. He had a very positive view of the Peace Corps, and he recognized its importance to the relationship between the United States and his country.

We went upcountry to visit a volunteer who was a high school math teacher in a very remote part of Tanzania. In many places in the developing world, it’s challenging to find and hire science and math teachers for rural communities, who are desperately needed, as without these subjects, the students in this region would not be able to complete the coursework required to take the qualifying exams for university applications. The school principal and our PCV were very proud of the role he played in this school and of the astronomy program he created to introduce his students to this area of science.

Upon our return to Dar, we had the pleasure of attending a lovely dinner hosted by the ambassador and participating in a fiftieth-anniversary gala, organized by Peace Corps staff and the PCVs. Due to a touch of serendipity, there happened to be several Peace Corps volunteers in Tanzania who were graduates of performing arts programs in universities and colleges across the United States. They created, planned, rehearsed, and staged a magnificent performance about the history of the Peace Corps in Tanzania. The audience included current PCVs, returned volunteers, Tanzanian government officials, Peace Corps partners, and special guests. From my humble viewpoint, it was a Broadway-caliber stage performance. It included concert singing, highly skilled theatrical performances, original music scores by soloist performers, and poetry readings as odes to Tanzanian–U.S. friendship. There we were, on the beautiful lawn and garden grounds of the U.S. Embassy, being entertained by this incredibly talented group of volunteers who expressed their love for Tanzania in the most heartfelt, dramatic fashion possible.

In November of 2011, my team and I traveled to the Philippines to celebrate the joint fiftieth anniversary of USAID and the Peace Corps. My colleagues Elisa Montoya, Esther Benjamin, and Jeff West accompanied me on this trip. As in Thailand, Ghana, and Tanzania, the Peace Corps program in the Philippines was legendary, again launched by Sargent Shriver nearly fifty years earlier.

Benigno Aquino III was the son of prominent political leaders Benigno Aquino Jr. and Corazon Aquino, the former president of the Philippines.5 President Aquino was a strong supporter of the Peace Corps. In his youth, he had become friends with several PCVs in his hometown and had met many PCVs during his mother’s presidency.

Our ambassador, Harry Thomas, a distinguished veteran diplomat, had served as the head of the Foreign Service as director-general. USAID mission director Gloria Steele was also a veteran USAID officer and former colleague who had held several senior positions at headquarters. She had the honor of being the first Filipina American to serve in this position. Needless to say, Gloria was well known throughout the country and highly regarded across the Philippines. Our terrific country director, Denny Robertson, represented the Peace Corps.

The president graciously hosted a luncheon for our group in the historic Malacañang Palace, his official residence and principal workplace— the White House of the Philippines. Many meetings between Filipino and U.S. government officials have taken place there over the years of the countries’ bilateral relationship. We had a delightful, wide-ranging conversation with the president and his staff in which he made clear his great appreciation for PCVs’ years of service. He was pleased that we were there to celebrate the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of this highly respected American organization.

Excerpt adapted from A Life Unimagined: The Rewards of Mission-Driven Service in the Peace Corps and Beyond by Aaron S. Williams with Deb Childs. © 2021 University of Wisconsin-Madison International Division

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleDouglas Kelley holds a special place among those who helped inspire the Peace Corps. see more

In Memoriam: Douglas Kelley (1929–2022)

By Catherine Gardner

Photo courtesy the family of Douglas Kelley.

Douglas Kelley holds a special place among those who helped inspire the Peace Corps. As a student at Berea College in Kentucky, he was committed to international cooperation and civil rights. In his senior year in college, in 1951, he began laying the groundwork for the International Development Placement Association, a program to promote humanitarian service by placing people internationally in jobs with indigenous organizations and governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Within three years the program had sent 18 young Americans abroad and had numerous applicants.The proof of concept helped inspire Senator Hubert Humphrey to propose legislation to create a peace corps in 1957. The idea evolved into what became formally known as the Peace Corps, enacted by President Kennedy by executive order in March 1961.

“I really wanted to serve overseas,” he recalled years later, “not as an officer in an air-conditioned office but doing the kind of thing Volunteers were doing. So, off we went to Cameroon.”

Kelley worked as the agency’s first community relations director. “I really wanted to serve overseas,” he recalled years later, “not as an officer in an air-conditioned office but doing the kind of thing Volunteers were doing. So, off we went to Cameroon.” We included his wife, Cynthia Kelley, and their two sons. Kelley served as a Volunteer in Cameroon 1963–65, helping to create a crafts marketing cooperative that doubled the monthly incomes of local artisans as their products were exported to the U.S.

A commitment to ending discrimination also shaped Kelley’s life. In 1957 he participated in Martin Luther King Jr.’s Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom at the Lincoln Memorial. He was later arrested for participating in a sit-in during the civil rights movement. He went on to direct programs training young people, to transform a decrepit textile mill into an arts center, and to help auto workers retrain. He died in January 2022 at the age of 92.

This remembrance appears in the Spring-Summer edition of WorldView magazine.

Catherine Gardner is an intern with WorldView. She is a student at Lafayette College.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleHeyman served as the first woman training officer for the Peace Corps in 1961. see more

In Memoriam: Juliane Heyman (1925–2022)

By Catherine Gardner

Photo of Juliane Heyman courtesy Alana DeJoseph

Born in the Free City of Danzig, now Gdansk, Poland, Julie Heyman was 12 years old when she fled her home due to increasing Nazi persecution. After months of being disconnected from her parents, she and her family were reunited in Brussels.

They fled again when the Nazis invaded Belgium. In 1941, Heyman arrived in New York by freighter. She graduated from Barnard College before earning master’s degrees in international relations and library science from U.C. Berkeley.

In what she calls one of her “most satisfying and exciting experiences,” she served as the first woman training officer for the Peace Corps in 1961. She worked 1961–64 in Washington, D.C. as a library advisor to several countries and international development consultant to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In 2003 she published From Rucksack to Backpack, recollections of her life and travels from the 1940s to 1960s.

Heyman was always ready to face any challenge and saw her experiences as testaments to learning how to understand different people and perspectives. She died in April at age 97.

This remembrance appears in the Spring-Summer edition of WorldView magazine.

Catherine Gardner is an intern with WorldView. She is a student at Lafayette College.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an article‘Posting Peace’ brings together posters from 1961 to 2022 see more

Posting Peace in Portland

Peace Corps Posters 1961–2022

If you’re near Portland, Oregon, before October 16, be sure to visit ArtReach Gallery for the exhibit Posting Peace. Co-hosted by the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience, it features six decades of Peace Corps posters and maps. The exhibit and an accompanying book are curated by gallery director Sheldon Hurst.Collectors in Oregon, California, Illinois, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere contributed. The exhibit is also made possible thanks to First Congregational UCC, Portland Peace Corps Association, and NPCA.

Special events connected to the exhibit take place in September and October. On September 18, former Peace Corps Director Jody Olsen delivers the Oliver Lecture. On October 6, Peace Corps CEO Carol Spahn — who has been nominated by President Biden to serve as Peace Corps Director — gives a talk on “Answering the Call to Serve Today.” And on October 16, for the closing reception, the gallery hosts a screening of A Towering Task: The Story of the Peace Corps, followed by a Q&A with filmmaker Alana DeJoseph.

Explore: artreachgallery.org

Poster images courtesy Museum of the Peace Corps Experience and ArtReach Gallery

-

Steven Saum posted an articlePhotographs from the city of Arak and central Iran from 1967–69 see more

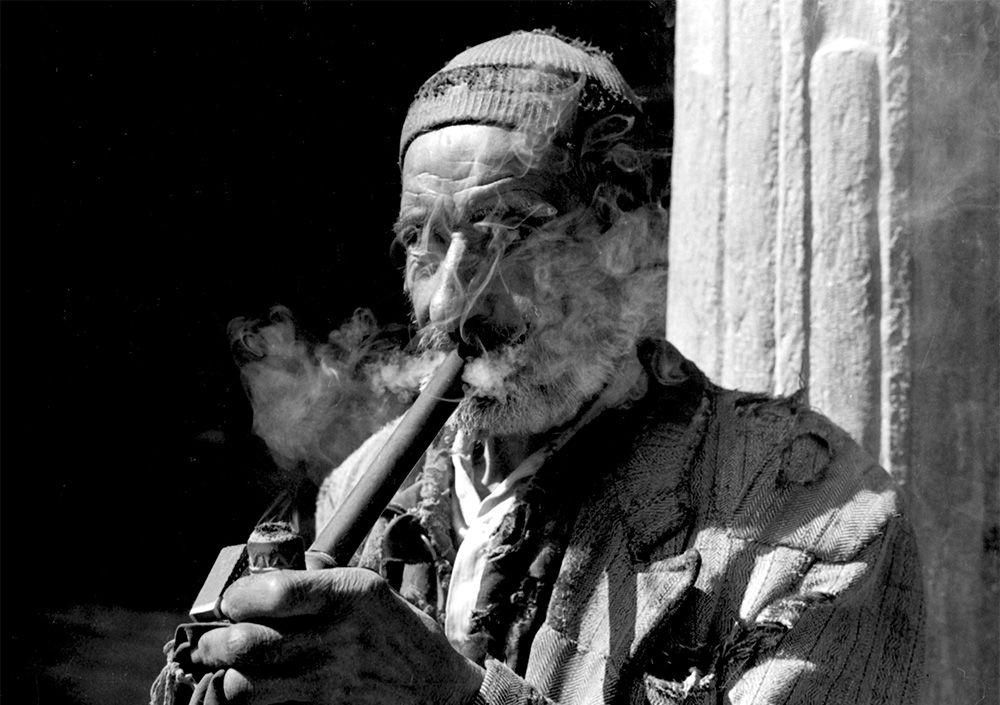

A selection from Dennis Briskin’s photos from Iran in the late 1960s. His book was recognized with the Rowland Scherman Award for Best Photography Book by Peace Corps Writers.

By NPCA Staff

Dennis Briskin has published a collection of 60 photographs from the city of Arak and central Iran, where he served as a Peace Corps Volunteer 1967–69. Briskin writes that he calls the collection The Face of Iran Before… because these photographs were taken before “the Islamic Revolution took the country back to oppressive intolerance and brutality. Before oil wealth brought engines and electric motors to replace mule, camel and horsepower, sometimes even human power, for pushing, pulling, lifting and carrying. Before towns spread out to become cities, and the capital spread up and out to become a dense, polluted metropolis.”

This is a companion to a 2019 collection of Briskin’s photos, Iran Before. Here, in The Face of Iran Before…, the photos focus on the faces of people he saw. “How much you see and understand depends on what you bring to the seeing,” Briskin writes. “We see and respond through our personal filters: what we love, what we want, what we fear and who we think we are. If you see below the surface in these 60 photographs, you may know the people of Iran better than the 22-year-old man behind the camera. I saw more than I understood. I understood more than I can say.”

A selection of Briskin’s photos also appears in the print edition of the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Read more from Dennis Briskin here.

Smoke and shadow.

Cover photo: A woman smiles as she adjusts her chador.

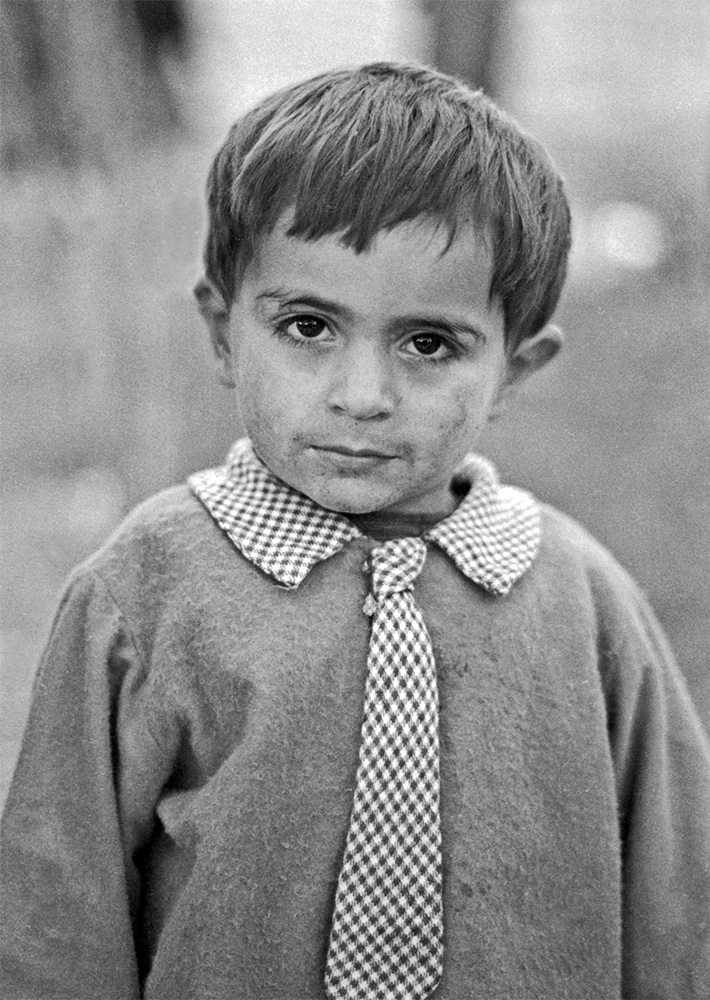

A young boy who was the sixth child after five girls and much beloved. He died young.

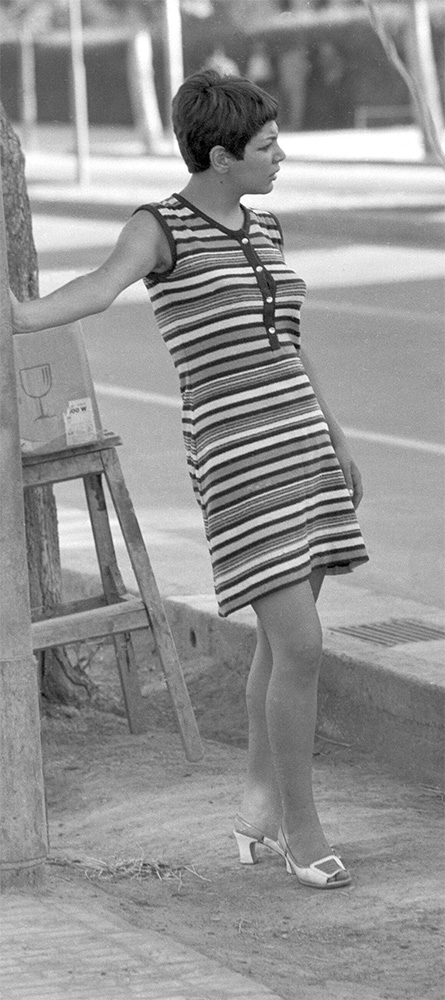

A woman in conversation in Hamedan. She and her male companion had parked a Mercedes sedan on the main street.

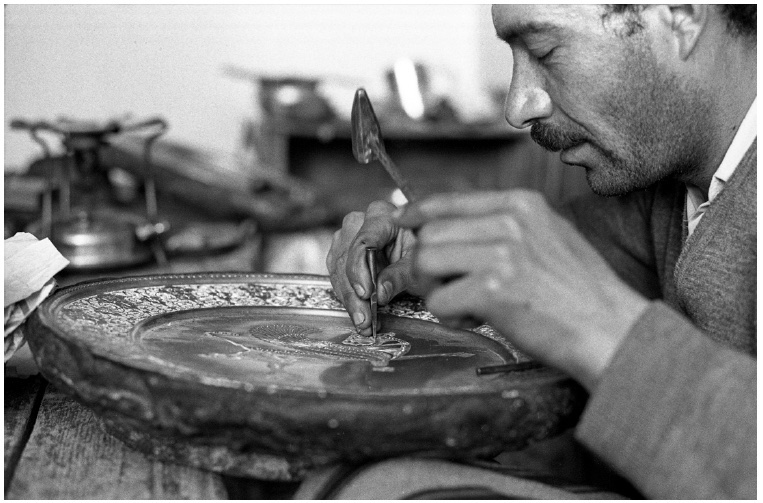

Fine silversmithing takes intense concentration, steady hands, sharp vision. Visitors to Esfahan love the metal craftwork.

“I love the pure contrast of light and dark,” Briskin writes. “Her smile touches my heart.”

Story updated May 3, 2022.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA guide to sharing people's stories consciously and with respect see more

A video and workbook to help Volunteers — and those who served years ago — think about storytelling. That includes intercultural dialogue and awareness of whose voices are at the center of a story.

By NPCA Staff

Image courtesy Peace Corps video

Shortly before the first Volunteers began returning to service overseas in March 2022, the Peace Corps agency published an Ethical Storytelling Toolkit. How we tell our stories — and the voices at the center of these stories — have informed discussions inside and outside the Peace Corps in recent years. A focus on ethical storytelling was also an important part of the conversations that shaped the “Peace Corps Connect to the Future” town halls and global ideas summit convened by NPCA in 2020.

A focus on ethical storytelling was also an important part of the conversations that shaped the “Peace Corps Connect to the Future” town halls and global ideas summit convened by NPCA in 2020.

The new toolkit includes a workbook and video; links for how returned Volunteers can get involved in the Global Connections program (formerly known as Speakers Match) to share their Peace Corps experience with audiences in the U.S.; and a range of tools, video resources, and useful facts and figures.

In terms of substance, “Ethical storytelling is a practice of sharing stories in a way that is conscious of power dynamics and grounded in mutual respect,” the toolkit notes. Intercultural dialogue is at the heart of the Peace Corps’ mission. So it makes sense for there to be an intentional and thoughtful commitment to storytelling shaped by that awareness. For Peace Corps, that means an approach “rooted in building and celebrating person-to-person relationships, and tied to our approach to intercultural competency, diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Read more and download the kit here.

This story appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated May 2, 2022.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleSonja Krause Goodwin's extraordinary time in the early years of the Peace Corps see more

My Years in the Early Peace Corps

Nigeria, 1964–1965 (Volume 1)

Ethiopia, 1965–1966 (Volume 2)By Sonja Krause Goodwin

Hamilton Books

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Sonja Krause Goodwin had already traveled far from home, earned a doctorate in chemistry, and worked for six years as a physical chemist when she joined the Peace Corps. Born in St. Gall, Switzerland, in August 1933, she had fled Nazi Germany with her family and resettled in Manhattan, where her parents opened a German bookstore. Sonja entered elementary school without speaking a word of English.

Science is where she found her calling. She earned her bachelor’s in chemistry at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and her Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1957. After working six years in industry, she joined the Peace Corps and headed for Nigeria. She led the physics department at the University of Lagos until she and the other Volunteers had to leave the country in 1965 due to a politically motivated “university crisis.”

She was reassigned to teach chemistry at the Gondar Health College in Ethiopia 1965–66, a college that also served as the local hospital. On her return to the U.S., she accepted a position at RPI and taught there for 37 years, advancing through the positions of associate professor and professor, and retiring in 2004. These memoirs were published in fall 2021, shortly before Goodwin’s death on December 1, 2021.

Story updated May 2, 2022.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleBill Novelli’s lessons in life and leadership see more

Good Business

The Talk, Fight, Win Way to Change the World

By Bill Novelli

Johns Hopkins University Press

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

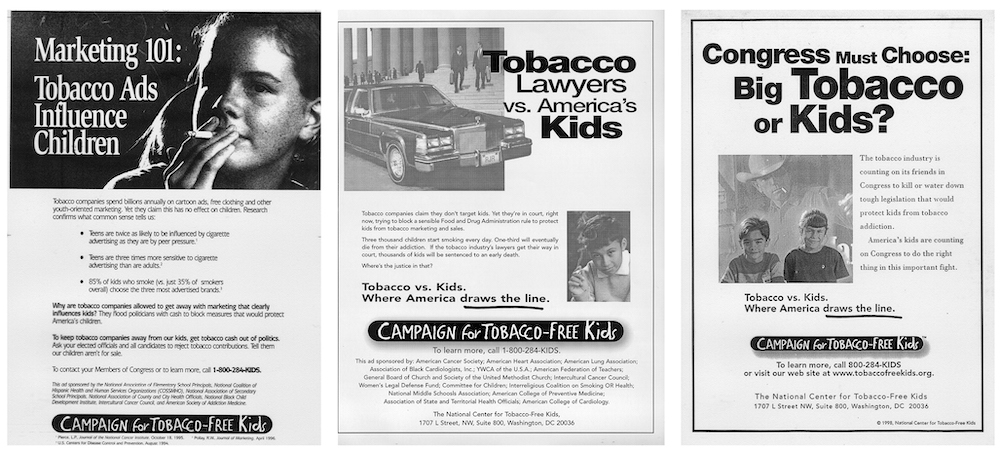

Bill Novelli’s career includes serving as CEO of AARP, founding the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, leading the humanitarian organization CARE, and establishing global PR agency Porter Novelli. He teaches in the MBA program at McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University. In Good Business, he offers lessons on life and leadership.

He got his start in the corporate world with Unilever, selling soap. Next stop: a New York ad agency, where he sensed a kind of social relevance to the work — sometimes. “The turning point came the day I returned from a client meeting with two test products in plastic bags, one a new kids’ cereal and the other a new soft, extruded dog food. A young copywriter came into my office, announced that he was working on ad concepts for the cereal and asked to see the product. As a joke, I pulled out the dog food and tossed it to him. Without much of a glance, he caught it and said, ‘Yeah, we can sell that.’”

Novelli took on a new client: the Public Broadcasting Service, seeking to build viewership. A while later he saw an ad in The New York Times that the Peace Corps, about a decade after its founding, was looking to reposition itself and seeking marketing expertise. Host countries “wanted more older and experienced Volunteers (nurses, agriculturalists, MBAs) and more people who looked like the citizens of the countries in which Peace Corps Volunteers served,” he writes. A headhunter whom Novelli called tried to steer him to a gig with Avon; no, Novelli said — Peace Corps.

“The other side of the equation is to be bigger than ourselves and go beyond our own personal interests and needs — to care about our communities, our country, and future generations.”

“Today there are nearly 250,000 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers and former staff, many of them, like me, members of the National Peace Corps Association, acting in support of the organization and its work,” he writes. (Hear! Hear!) While working on PR for the agency, Novelli conducted a survey of returned Volunteers. He notes that when he asks current Georgetown students (some RPCVs) “what they think returning Volunteers’ main concern was, they often guess it was about getting a job or fitting back into American society. But the biggest concern back then, and I feel certain it remains so today, was the fear that the sand would blow over their tracks and that all their hard work in the country where they had served would disappear. This fear was well founded, as I learned later in my work for CARE.”

In 1995 Bill Novelli left CARE to found and lead the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Images courtesy Bill Novelli

Novelli chronicles two ethical lapses in his own career — not coincidentally, after he moved from the Peace Corps to Pennsylvania Avenue and the November Group, an ad agency formed in 1972 with one client and one purpose: Keep Richard Nixon in the White House. “We were housed in the same space as the Committee to Re-elect the President, which became known as CREEP. A lesson here: watch what names spell out in acronyms.”

Novelli serves his tale with dashes of humor. He also asks some big questions — about society, the environment, and more — particularly in the last chapter, “What Do We Owe Our Grandchildren?” Personal responsibility is part of it, he notes. “But the other side of the equation is to be bigger than ourselves and go beyond our own personal interests and needs — to care about our communities, our country, and future generations.”

This review appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleIn the mountains near Oaxaca, tales of El Norte: among weavers and migrant workers who returned see more

In the mountains near Oaxaca, tales of El Norte: among weavers and migrant workers who left family and home for work across the border — and returned. Conversations from a time before COVID.

By Paul Theroux

On a sojourn in pursuit of understanding, writer Paul Theroux set out five years ago to travel the length of the U.S.–Mexico border. Then he drove his old Buick south, visiting villages along the back roads of Chiapas and, here, a mountain town near Oaxaca. An excerpt from On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey.

In the small Zapotec-speaking town of San Baltazar Guelavila, I asked Felipe, a local man, the meaning of “Guelavila.”

“It means Night of Hell, sir,” Felipe said.

“And this river?”

“It is the River of Red Ants, sir.”

“That hill is impressive.”