Dreams and disillusionment. A 3,000-mile ultramarathon and a library in a Mayan village. Catching up with books recognized with the Peace Corps Writers Awards.

Baked into the mission of the whole Peace Corps experience is the work of telling stories: of listening, catching, giving voice and shape and form with a sense of fidelity to people and place, and an awareness of audience. Nurturing stories from the Peace Corps community in words and images can be a way to foster understanding and empathy, stuff lately in short supply. Back in 1989, returned Volunteers John Coyne and Marian Haley Beil launched a print publication that has grown into the digital environment known as Peace Corps Worldwide, which is an affiliate group of National Peace Corps Association. They also began publishing books by Peace Corps writers. In 2020 they recognized the following books with Peace Corps Writers awards.

Moritz Thomsen Award for Best Book about the Peace Corps Experience

Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia

Peace Corps Volunteers’ Accounts of Their Adventures, Challenges, and Achievements

(Peace Corps Writers)

Read more in this review by Barry Hillenbrand.

Bill Owens

Altamont 1969

(Damiani)

December 1969. Bill Owens is working as a photographer for the Livermore Independent when friend Beth Bagby, another photojournalist who shoots for AP, calls and asks if he wants to join her and photograph the free concert at the Altamont Speedway, in hills to the east of San Francisco Bay, with the Rolling Stones as headliners. It will be the West Coast answer to Woodstock. Owens’s editors give him the day off in exchange for giving them dibs on photos.

Saturday morning, December 6: Owens rides to Altamont on his motorcycle. Speaking of bikes: Hells Angels are providing security for the show and are being paid in beer. Three hundred thousand people show up at a venue where preparation had begun only two days before.

On the bill with the Stones: Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Flying Burrito Brothers, plus Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. The Grateful Dead are scheduled to play too, but don’t. Acid, wine, and mayhem are there aplenty.

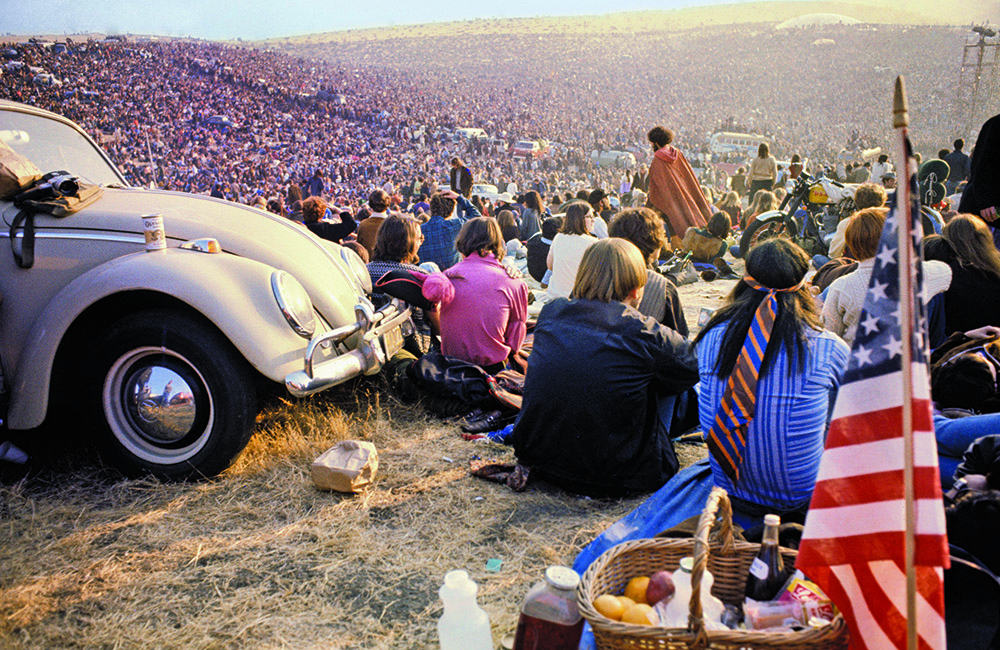

Bug, beer, flag — and a “sea of people with no borders, no limits, and no shepherds,” writes Sasha Frere-Jones. “The only protection for the band was a comical piece of sisal twine stretched across the stage.” The twine didn’t last long. Photo by Bill Owens.

Perched in a sound tower with two Nikons, three lenses, 13 rolls of film, a sandwich, and a jar of water, Owens shoots the scene: hippies in corduroy and afghans and birthday suits, dancers and trippers, Mick Jagger led by cops through the crowd, Hells Angels beating a man with a pool cue. When a biker threatens to clobber Owens with a pipe wrench and break his effing skull unless he comes down, our intrepid photog flashes his press card. The Angel is not impressed.

Owens decides it’s time to bail. Before the day is done, one Black man, Meredith Hunter, is stabbed to death. Another man tripping on acid drowns in an irrigation ditch; two more are killed in a hit-and-run.

Music, acid, wine, vioolence. Photo by Bill Owens.

Four decades later comes Altamont 1969, with new and previously unpublished photographs from that day. Some call it rock ’n’ roll’s darkest hour, the end of the peace and love ’60s. Back in the day, Bill Owens published some photos under a pseudonym; he didn’t want the Hells Angels coming for him or his family, thinking he had photographed the murder of Hunter. Indeed, when Owens and friend Beth Bagby loaned some negatives to a married couple who planned to publish a book, that couple’s house was burglarized, the negatives stolen. Some of the negatives that survived are what make up this book.

Faces in the crowd. Photo by Bill Owens.

Owens served as a Volunteer in Jamaica 1964–66, an experience that launched his career in photography. He made a name for himself as a photographer with the big-thinking and warmhearted series Suburbia — profoundly different than the work in Altamont. He has also made a name for himself with Buffalo Bill’s Brewery as a pioneer in the craft beer movement. His encore to that: trailblazing work in craft distilling.

Paul Cowan Award for Best Book of Nonfiction

Charles B. Kastner

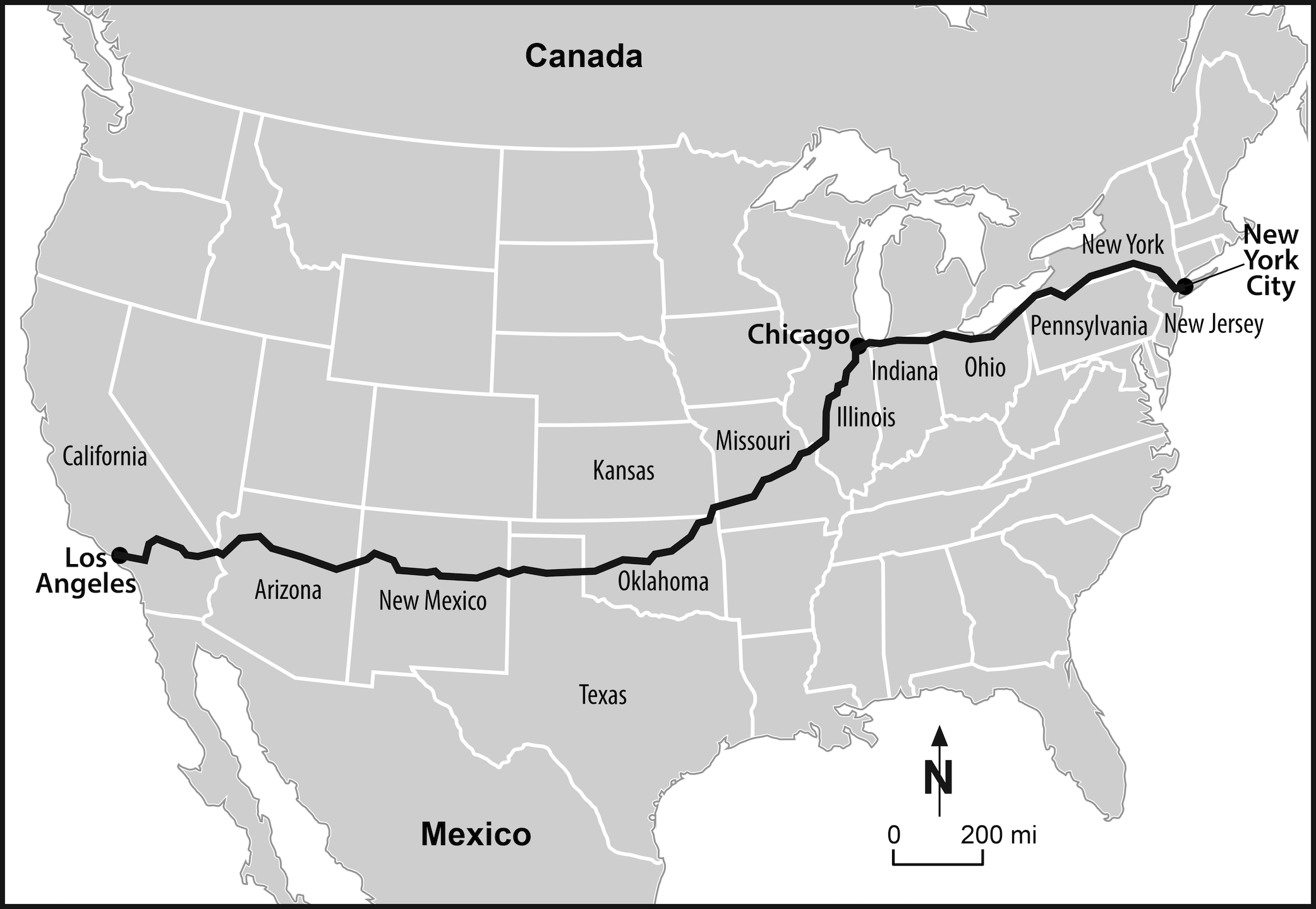

Race across America: Eddie Gardner and the Great Bunion Derbies

(Syracuse University Press)

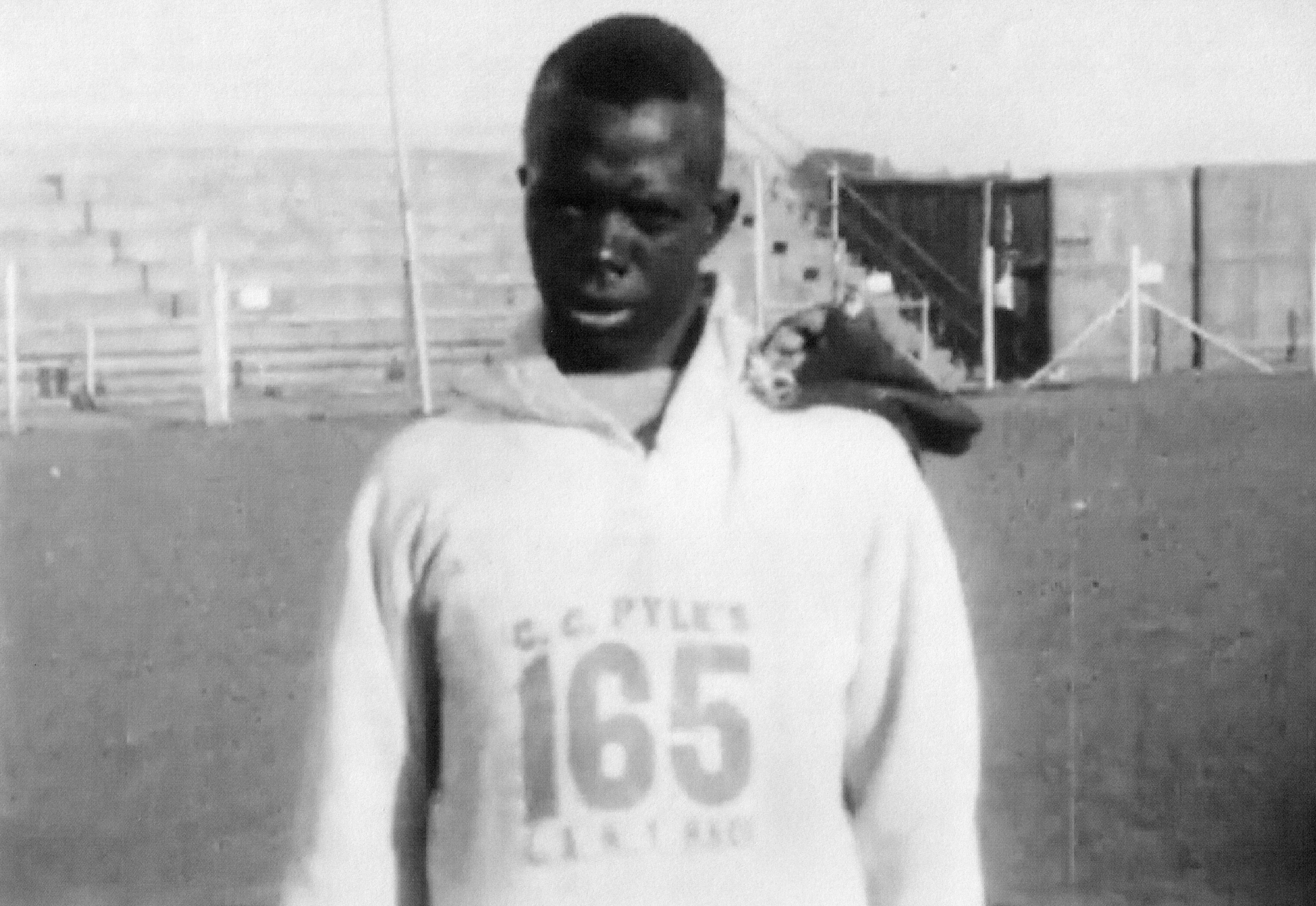

Charles Kastner traces Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner’s remarkable journey from his birth in 1897 in Birmingham, Alabama, to his success in Seattle as one of the top long-distance runners in the Northwest, and finally to his participation in two transcontinental footraces where he risked his life: As a Black man, he faced a barrage of harassment for having the audacity to compete with white runners. Kastner shows how Gardner’s participation became a way to protest the endemic racism he faced, heralding the future of nonviolent efforts that would be instrumental to the civil rights movement. Kastner served as a Volunteer in the Seychelles 1980–82.

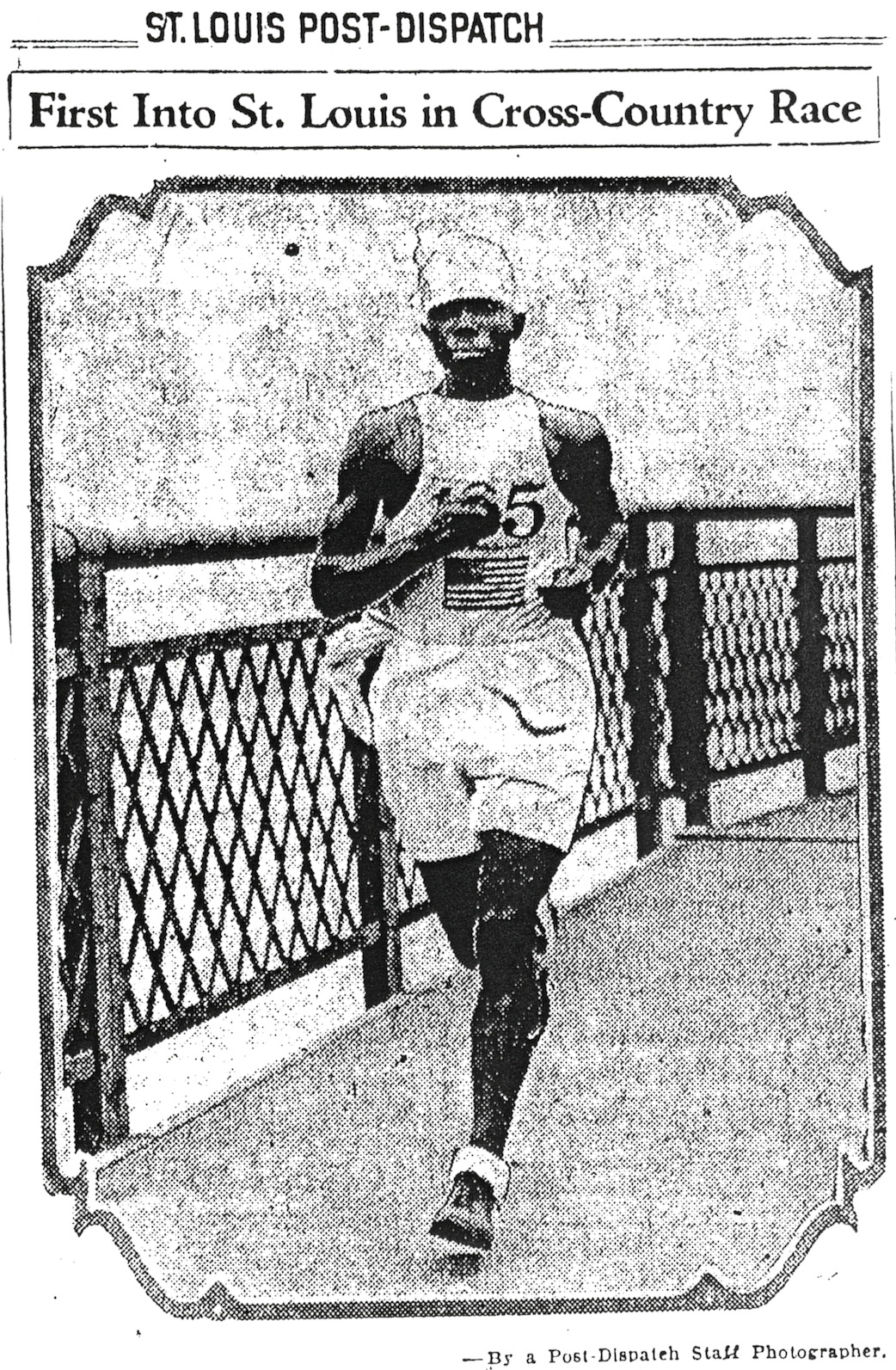

From the book: On April 23, 1929, the bunion derby returned to the Jim Crow South. On that day, Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner, an African American runner from Seattle, Washington, was leading the bunion derby across the Free Bridge over the Mississippi River that separated Illinois from Missouri. He was flying, blazing over the short, by derby standards, twenty-two-mile course at a sub-three-hour marathon pace.

“First into St. Louis in Cross Country Race”—with the American flag on his chest. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1929.

Eddie was wearing the distinctive outfit that earned him his nickname, a white towel tied around his head and a white sleeveless shirt and white shorts, but he had added something new to his outfit. Below his racing number, “165,” he had sewn an American flag, a reminder to all who saw him run that he was an American and, that day, the leader of the greatest footrace in the world. He was setting himself up for another collision with southern segregation.

Peace Corps Writers Award for Best Short Story Collection

Kristen Roupenian

You Know You Want This: “Cat Person” and Other Stories

(Gallery/Scout Press)

Spanning a range of genres and topics — from the very mundane to the murderous and supernatural—these are tales of sex and punishment, guilt and anger, the pleasure and terror of inflicting and experiencing pain. “Cat Person,” published in the New Yorker, garnered deserved acclaim. Reviewer Marnie Mueller zeroed in on the collection’s narrative pace, edgy dialogue, descriptive power, and dark humor. The stories fascinate and repel, revolt and arouse, scare and delight in equal measure. As a collection, they point a finger at you, dear reader, daring you to feel uncomfortable — or worse, understood — as if to say, “You want this, right? You know you want this.” Roupenian served as a Volunteer in Kenya 2003–05. She was named to the inaugural National Peace Corps Association “40 Under 40” list, published in our spring 2020 edition; her fiction has appeared in these pages as well.

Nancy Heil Knor

Woven: A Peace Corps Adventure Spun with Faith, Laughter, and Love

(Peace Corps Writers)

Through intimate first-person accounts and letters, Woven invites readers to accompany Knor on her journey into the jungles of Belize, where she served as a Volunteer 1989–91. She introduces readers to Mayan families she comes to love; she seeks deeper understanding of the dynamics of the K’ekchi Maya culture — and helps build a library.

William Siegel

With Kennedy in the Land of the Dead: A Novel of the 1960s

(Peace Corps Writers)

The novel begins on the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas: November 22, 1963. Gilbert Stone, a Peace Corps Volunteer teacher in Ethiopia, returns home, shattered by the loss of his hero. In the years that follow, Stone struggles to integrate his Peace Corps experience and the trauma of Kennedy’s death. Siegel himself served as a Volunteer in Ethiopia 1962–64.

Bill Preston

Strange Beauty of the World: Poems

(Peace Corps Writers)

These poems invite reflection: on how past impinges on present, how events long ago inform who we are now; on paths taken and not taken, and unintended consequences of those choices. They ask us to bear witness to cruelty and injustice; to summon the creative imagination to resist the mundane, challenge the rehearsed response. They pay homage to beauty and its weird, wonderful diversity and expression. Preston served as a Volunteer in Thailand 1977–80.

Steve Kaffen

Europe by Bus: 50 Bus Trips and City Visits

(SK Journeys)

Through 50 journeys over a two-year period, traveler and prolific author Steve Kaffen — who served as a Volunteer in Russia 1994–96 and once met Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary hiking in the Himalayas — weaves together a fascinating travelogue with experiential guidance on how to explore Europe by bus — something that, in the age of COVID-19, suddenly belongs to another time.