In 1967, Jack Allison wrote and recorded a song that went on to be the No. 1 hit in Malawi for two years running. Then the president kicked him out of the country.

45 RPM: “Ufa Wa Mtedza (The Peanut Flour Song)” — No. 1 in Malawi 1967–70. Photo courtesy Jack Allison

The Warm Heart of Africa

An Outrageous Adventure of Love, Music, and Mishaps in Malawi

By Jack Allison

Peace Corps Writers

Jack Allison served as a Volunteer 1967–69 in Malawi, a country known as “The Warm Heart of Africa.” While there, he wrote and recorded the number one hit song in the country, and Newsweek magazine reported that he was more popular than Malawi’s president. That didn’t please the president.

Prior to Peace Corps service, Allison overcame an impoverished and dysfunctional home life. He made his way to Warren Wilson College and to the University of North Carolina, where he sang with the glee club, performed on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and toured Europe. The experience enabled his unique contribution to public health in Malawi.

Allison’s story weaves through village life, a dog, motorcycles, a robbery, snakes, and love, but mostly it is a remarkable merging of music and medicine that captured the attention of the entire country. He returned to the U.S. to become a nationally prominent emergency room and public health physician.

—Chic Dambach (Colombia 1967–69)

Peanut Flour, Peace Corps, and the President: A Conversation with Jack Allison

By Jake Arce for WorldView magazine

WorldView: What motivated you to walk into the Peace Corps office at the University of North Carolina?

Jack Allison: I wanted to do something worthwhile. I’d been an undergrad at Warren Wilson College; 20 percent of the student body was international — people from Kenya, Lebanon, India, Greece, Fiji Islands, Finland. I trained for three months to go to Nigeria. Because of civil war in Biafra, they said, “It’s too dangerous. You’re going to go to Malawi.” I didn’t know where Malawi was. For training, they sent us to Puerto Rico, for a one-month immersion in Chichewa. If I sat down at lunch and said, “Please pass the salt,” they’d say, “No. Say it in Chichewa.”

WV: You got to Malawi in 1967 and recorded a song early on. What was it like to hear it on the radio?

Allison: I hadn’t been there but 13 weeks or so. I went to get my hair cut — I was getting a little shaggy. While I was in the barbershop, the radio station — the only one in the country — played my song “Brush the Flies Out of Your Babies’ Eyes.” The guys started talking about it. One guy says, “Hey, who is this?” The guy cutting hair says, “It’s Jack something or other — he’s a Peace Corps Volunteer, I think.” It took a while — waiting, then for him to cut my hair. They played my song again within 15 minutes. The guy cutting hair says, “I heard that song six times yesterday.”

It was crazy. On the way back, I wrote the song that really went viral: “Ufa Wa Mtedza” in Chichewa, or “The Peanut Flour Song.” It became the number one song in Malawi for three years.

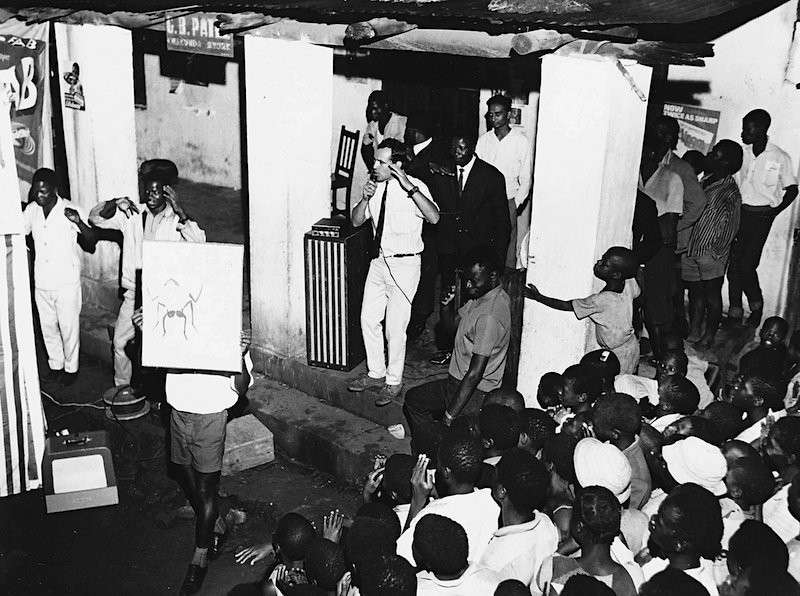

Live gig: Jack Allison, with mic, onstage. Photo courtesy Jack Allison

WV: With a catchy surf beat.

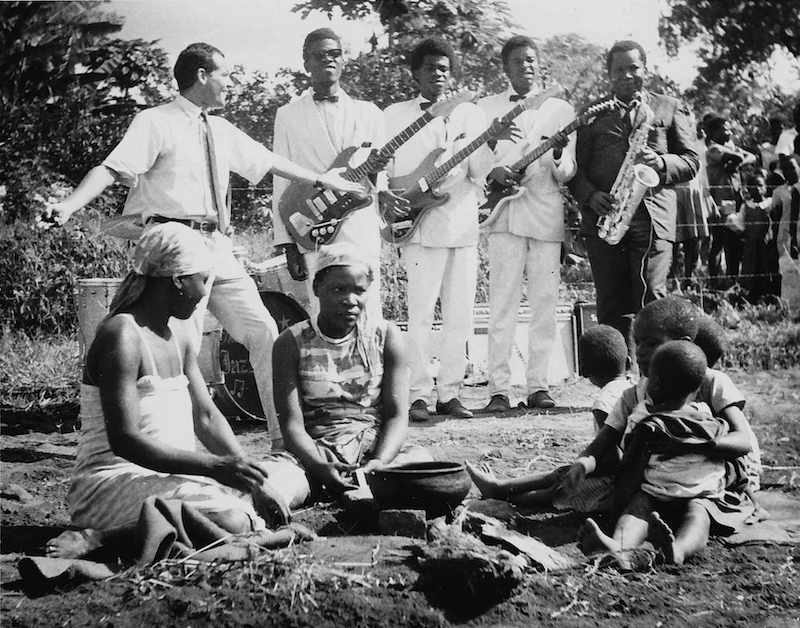

Allison: I literally translated flour of/from peanuts as three words: Ufa wa mtedza. There’s one word for that in Chichewa — nsinjiro — but I hadn’t learned that yet! I think Malawians found that a little odd. But the rhythm of the words works. The message was about providing nutrition for kids. I recorded it with the most popular African band in Malawi, the Jazz Giants. Of all the songs I recorded there, only two were not with them. One was with the Woodpeckers, another popular band; I did a jingle about the wonders of fertilizer. The last song I recorded in Malawi was about how “we must take good care of our health.” I wasn’t able to bring home a recording, because I got thrown out of the country! That’s the tune I used recently for an anti-COVID-19 song in Chichewa, distributed throughout Malawi. I’m trying to make a modest contribution to protect Malawians from COVID.

WV: You fell ill and were sent to the States. Did you think the experience in Malawi was over?

Allison: I was scared to death. I was sicker than a darn goat before I left Malawi; by the time I got to see a gastroenterologist in the States, I was healed. They did everything — a colonoscopy and upper GI exam. At the end of a month, the doctor said, “You’re good to go. You’ve been good to go since I first saw you, but I had to make sure.” I went to Peace Corps HQ and they told me they weren’t going to send me back because I only had five months left. But I was politely persistent; I showed up every day and eventually demanded to see the director, Jack Hood Vaughn. He had called the Peace Corps country director in Malawi and said, “Thumbs up or thumbs down?” The country director said, “His music is popular, he wants to do more, please allow him to come back.” I got to return, then extended for a third year.

I just had an enchanted experience. Obviously, the music was the biggest piece — and touring the country for five months. I’m still fluent in conversational Chichewa.

Singing for the cameras: Jack Allison and the Jazz Giants. Photo courtesy Jack Allison

WV: You were thrown out of Malawi — and Peace Corps was going to be shut down.

Allison: President Hastings Banda didn’t like the Peace Corps. Two things ticked him off. One, a lot of guys wore beards. I didn’t even have a mustache, and I wore a tie almost every day, especially in the clinic. For women, Banda wanted them to wear ankle-length skirts. Most Volunteers didn’t wear miniskirts, but some Brits and other expats did. There were a lot of Volunteers, so Banda would see a woman with a miniskirt and say, “That’s a Volunteer, and that’s ticking me off.”

Then a Newsweek article was published and the reporter said, “Jack Allison is more popular amongst the Malawian people than their president.” Dr. Banda was not amused. He made light of my music, said I made a lot of mistakes in speaking and singing in Chichewa, and he kicked me out. The next day he went on a rant and announced he was kicking out the Peace Corps. The health group that replaced mine went to the Congo instead. Programs in agriculture and health were decimated. Finally the Minister of Education went to the president and said, “If you follow through with this, you’re going to lose 60 percent of your teachers at the secondary level.” Reluctantly, Banda allowed Peace Corps to stay.

WV: It was a long time before you went back to Malawi — but you’ve returned a number of times since.

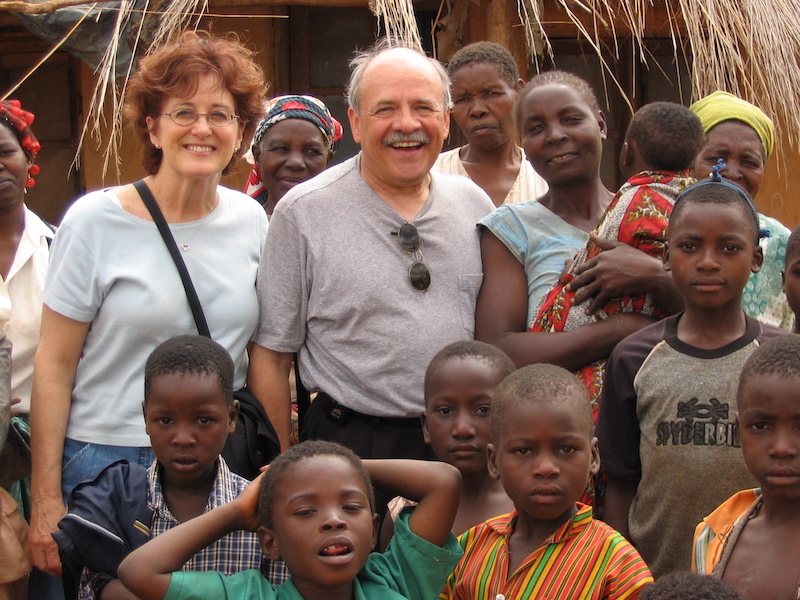

Welcome back, Jack: At Nsiyaludzu Health Centre, mothers and children with Jack Allison and wife Sue Wilson decades after Jack served as a Peace Corps Volunteer. Photo courtesy Jack Allison

Allison: In 1994, as the AIDS epidemic was worsening, I got a call — in fact, three. “People remember your music … Would it be possible for you to write three songs about AIDS?” I did, really quickly. That first week I was there, I wrote three more songs and recorded a six-track album, “Songs About AIDS” — or “Nyimbo za EDZI” in Chichewa.

Another project I got involved in was with Naomi Tutu, daughter of Desmond Tutu, and an Episcopal priest where I live in Asheville, North Carolina. For a group they supported called Girls Not Brides, I wrote a jingle in English about how boys and girls should reach the age of 18 before they get married. In Malawi, people will marry off a young kid who is 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. The family is paid a dowry. When the girl is eventually old enough to get pregnant but not fully developed, if the head of the baby is too big to go through the pelvis, that’s bad.

WV: You’re a physician. As we’ve been grappling with a global pandemic for many months, we’ve talked a lot about what the role of Peace Corps should be. And the ways it should change.

Allison: The number one concern, as an American, and as a physician, is safety. We’ve got to get the pandemic under control.

I serve on the NPCA Advisory Council — the only physician in that group. I’m pushing hard for two things. One, improve the health of Volunteers in the field. There are ways we can do this. Two, when Volunteers return after their close of service, if they’re ill or injured, they have 30 days to get better. Well, if you’ve got hepatitis B — or a broken leg that they didn’t set well and needs to be re-broken and reset — you’re not going to get better in 30 days. I'm on the committee with a woman who suffers from PTSD. You don’t get over that in 30 days. I don’t know if she’ll get over it in 30 years.

If the Volunteer is not better after 30 days, Peace Corps turns that chart over to the Department of Labor — and it goes into a black hole. Why is it sent to Labor? Because it’s workers’ comp-related. But fee schedules to pay the consultants are antiquated. If they get paid, it’s markedly less than they would expect. And a lot aren’t getting paid. So they say: “You get squared away with making sure that I’m up to snuff before I will see you again.”

The way to fix this is legislatively, so that’s what we’re trying to do.

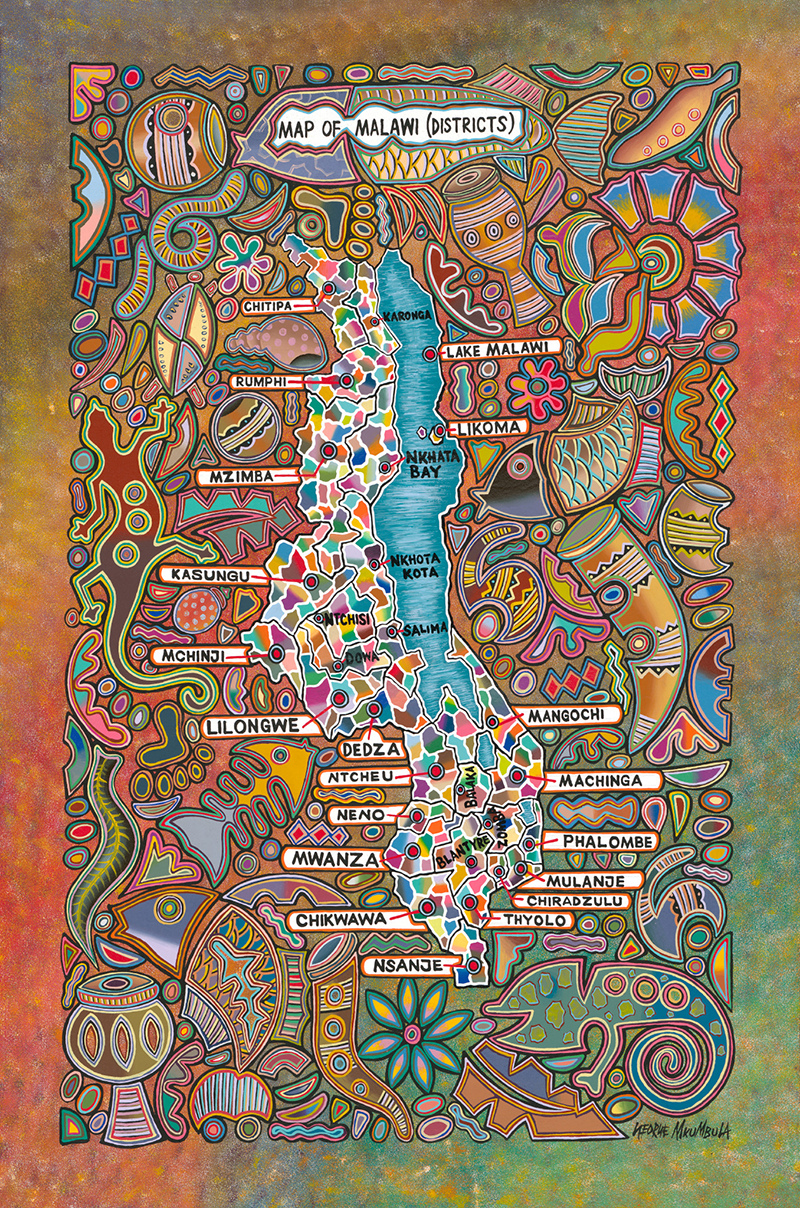

Malawi now: Artist George Mkumbula maps out the cultural diversity of his country. Map courtesy World Maps Collaborative. View more work by artists and purchase: theworldmapscollaborative.com

A version of this interview appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine. Story updated May 2, 2022.

Jake Arce served as an intern with WorldView magazine in 2021. He is completing a master’s in peace studies and conflict resolution at American University.