Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleHonoring global leaders in the Peace Corps community from Senegal, the Philippines, and the U.S. see more

Every five years, Peace Corps presents the John F. Kennedy Service Awards to honor members of the Peace Corps network whose contributions go above and beyond for the agency and America every day. Here are the 2022 Awardees.

By NPCA Staff

Photo: Dr. Mamadou Diaw, Peace Corps staff recipient of the 2022 JFK Service Award. Photos Courtesy of the Peace CorpsOn May 19, at a ceremony at the U.S. Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C., the Peace Corps presented The John F. Kennedy Service Awards for 2022. Every five years, the Peace Corps presents the JFK Service Award to recognize members from the Peace Corps community whose contributions go above and beyond their duties to the agency and the nation. The ceremony as also live-streamed around the world — since this is a truly global award, with honorees from Senegal, the Philippines, and the United States.

Join us in congratulating this year’s awardees for tirelessly embodying the spirit of service to help advance world peace and friendship: Liz Fanning (Morocco 1993–95), Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse (PCV: Guinea 2006–07, Zambia 2007–08; Response: Guyana 2008–09, and Uganda 2015–16), Karla Sierra (PCV: Panama 2010–12; Response: Panama 2012–13), Dr. Mamadou Diaw (Peace Corps Senegal 1993–2019), Roberto M. Yangco (Peace Corps Philippines 2002–Present).

RETURNED PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEER

Liz Fanning | Morocco 1993–95

Liz Fanning is the Founder and Executive Director of CorpsAfrica, which she launched in 2011 to give emerging leaders in Africa the same opportunities she had to learn, grow, and make an impact. Fanning has worked for a wide range of nonprofit organizations during her career, including the American Civil Liberties Union, Schoolhouse Supplies, and the Near East Foundation. She received a bachelor’s in economics and history from Boston University and a master’s in public administration from NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. She received the Sargent Shriver Award for Distinguished Humanitarian Service from National Peace Corps Association in 2019 and a 2021 AARP Purpose Prize Award.

RETURNED PEACE CORPS RESPONSE VOLUNTEERS

Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse, DNP, RN | Guinea 2006–07, Zambia 2007–08, Response: Guyana 2008–09, Response: Uganda 2015–16

Genevieve de los Santos Evenhouse grew up in the Philippines, then emigrated to the United States in 1997. She pursued a career at the intersection of nursing, public service, and volunteerism, earning her doctor of nursing practice in 2020 — while continuing to serve as a full-time school nurse for the San Francisco Unified School District. As a compassionate, socially conscious nurse dedicated to providing care and developing nurse education, Evenhouse has a keen affinity for teaching, community service, and cultural exchange that led her to serve in four countries — Guinea, Zambia, Guyana, and Uganda — as a Volunteer and Peace Corps Response Volunteer. She also volunteered at two health offices in the Philippines as a public health nurse as well as the Women’s Community Clinic in San Francisco as a clinician.

Karla Y. Sierra, MBA | Panama 2010–12, Response: Panama 2012–13

Karla Yvette Sierra was born in El Paso, Texas, to Mexican American parents. Sierra graduated from Colorado Christian University with a bachelor’s in business administration and a minor in computer information systems. Elected by her peers and professors, Sierra was appointed to serve as the Chi Beta Sigma president as well as the secretary for the student government association. Sierra volunteered with Westside Ministries as a youth counselor in inner city Denver. Shortly after completing her Master of Business Administration at the University of Texas at El Paso, she started working for Media News Group’s El Paso Times before being promoted to The Gazette in Colorado. Sierra served as a Volunteer in Panama for three years as a community economic development consultant focused on efforts to reduce poverty, increase awareness of HIV and AIDS, and assist in the implementation of sustainable projects that would benefit her Panamanian counterparts. Her Peace Corps experience serving the Hispanic community fuels her on-going work and civic engagement with Hispanic communities in the United States.

PEACE CORPS STAFF

Dr. Mamadou Diaw | Peace Corps Senegal 1993–2019

Dr. Mamadou Diaw — born in Dakar — is a Senegalese citizen. He studied abroad and graduated in forestry sciences and natural resource management from the University of Florence and the Overseas Agronomic Institute of Florence. He joined the Peace Corps in 1983 as Associate Peace Corps Director (APCD) for Natural Resource Management. In that capacity, he managed agroforestry, environmental education, park and wildlife, and ecotourism projects. From 1996 to 2001, he served as the coordinator of the USAID funded Community Training Center Program. In 2008, he switched sectors, becoming Senior APCD Health and Environmental Education. He received a master’s degree in environmental health in 2014 from the University of Versailles, and a doctorate in community health from the University of Paris Saclay, at the age of 62. Dr. Diaw coached more than 1,000 Volunteers and several APCDs from the Africa region, notably supporting Peace Corps initiatives in the field of malaria and maternal and child health. He retired from Peace Corps toward the end of 2019 and is currently working as an independent consultant.

Roberto M. Yangco (“Ambet”) | Peace Corps Philippines 2002–present

Ambet Yangco, a social worker by training, started his career as an HIV/AIDS outreach worker for Children’s Laboratory Foundation. He then served as a street educator in a shelter for street children and worked for World Vision as a community development officer. Twenty years ago, Yangco joined Peace Corps Philippines as a youth sector technical trainer. It wasn’t long before he moved up to regional program manager; then sector manager for Peace Corps’ Community, Youth, and Family Program; and now associate director for programming and training during the pandemic.

READ MORE and SEE PHOTOS from the 2022 JFK Awards ceremony here.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA film chronicling the work by Response Volunteers fighting COVID-19 in the U.S. in 2021 see more

On December 2 the agency premiered a film chronicling the work by Peace Corps Response Volunteers in 2021 to help fight COVID-19 in the United States.

By NPCA Staff

In 2021, for the second time in the agency’s 60-year history, Peace Corps Response Volunteers deployed in the U.S., at the request of FEMA, to support vaccination efforts.

We shared stories from some of those Volunteers in the Summer 2021 edition of WorldView. On December 2, the Peace Corps premiered a documentary, “Peace Corps Response to COVID,” following Volunteers through their three-month journey as they used skills honed during their Peace Corps service to help communities in need here at home. “The Peace Corps network is always prepared to meet the moment,” said Acting Director Carol Spahn, “whether that’s here at home or with our partner communities around the world.”

Watch: peacecorps.gov/premiere

This story appears in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleVolunteers Serving in Times of Need see more

In 2021 Peace Corps Response marks a quarter century since its founding. Some moments that have defined it.

Photo: Community members in a village near Zomba, Malawi, learn to sew reusable sanitary pads for girls. Sheila Matsuda captured the moment as a Response Volunteer in Malawi 2018–19.

Crisis Corps was launched in 1996. At the outset, Volunteers were deployed to respond to natural disasters and assist with relief in the aftermath of violence. Over the years, the program expanded in scope, and Volunteers are now sent to meet a variety of targeted needs in communities around the world. In 2007, the name of the program changed to Peace Corps Response to reflect this shift.

Here’s a little history — including the program’s origins.

1992 | Beginnings

NAMIBIA: Peace Corps approves first short-term assignments. Ten Volunteers already serving elsewhere transfer to Namibia, responding to a prolonged, devastating drought.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

1994 | April

RWANDA: The president is assassinated, and a campaign of genocide unfolds. Returned Volunteers work with National Peace Corps Association to activate the NPCA Emergency Response Network and deploy RPCVs to support work with refugees. Peace Corps, in conjunction with the International Rescue Committee, also transfers five Volunteers to the Burigi refugee camp, where they serve for five months.

1995 | September

LESSER ANTILLES bears the brunt of Hurricane Luis. More than 3,000 people are left homeless. Eight RPCVS re-enroll with the Peace Corps, travel to Antigua, and help rebuild homes and provide training on hurricane-resistant construction.

Photo: NASA

1996 | June 19

CRISIS CORPS is officially launched at a Rose Garden ceremony with President Bill Clinton and Peace Corps Director Mark Gearan. The Peace Corps is “based on a simple yet powerful idea: That none of us alone will ever be as strong as we can all be if we’ll all work together,” Clinton says.

Photo: Peace Corps

1996 | December

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB: Peace Corps Director Gearan announces plans for a “reserve” of up to 100 Crisis Corps Volunteers; some to travel to Guinea and Ivory Coast to work with Liberian refugees.

1997 | July

CENTRAL EUROPE hit by devastating floods. RPCVs who served in the Czech Republic return with Crisis Corps to assist relief efforts.

Photo: Bohumil Blahuš

1998 | September

CARIBBEAN countries blasted by Hurricane Georges; more than 300 killed. Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Volunteers in Dominican Republic help with home reconstruction and emergency water and sanitation projects.

Photo: Debbie Larson / National Weather Service

1998 | October

CENTRAL AMERICA slammed by Hurricane Mitch. Hundreds of RPCVs who served in the region contact the agency to serve; Volunteers already in the region assist, too. Relief efforts in Honduras, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Crisis Corps Volunteers have also served in Chile, following an earthquake, and in Paraguay in the wake of flooding.

2000 | June

HIV/AIDS CRISIS: Peace Corps Director Mark Schneider calls on RPCVs to consider devoting their time, skills, and experience to serve in Crisis Corps as part of a new HIV/AIDS initiative. Five African countries have requested Volunteers in this capacity.

Photo Credit: Peace Corps

2001 | April

BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA: Crisis Corps Volunteers begin assignments in first country where Peace Corps had no prior presence. They assist local municipalities and NGOs, plus international aid organizations.

2002 | January

MAURITANIA hit by torrential rains, causing severe flooding. Red Crescent of Mauritania requests Crisis Corps assistance to help homeless families.

Image: Jon Harald Søby

2002 | February

AFGHANISTAN: After the swearing-in of new Peace Corps Director Gaddi H. Vasquez, President George W. Bush announces that a Peace Corps team will travel to Afghanistan to assess how the program could help with reconstruction. It is possible a Crisis Corps team could follow. But Volunteers do not return to Afghanistan.

Photo: Alejandro Chicheri / World Food Programme

2002 | July

MICRONESIA struck by Typhoon Chataan, most devastating natural disaster in the country’s history. On the island of Chuuk, Crisis Corps Volunteers assist with reforestation and soil stabilization, and begin work with communities on water sanitation facilities.

Photo: Federated States of Micronesia Department of Foreign Affairs

2002 | November

MALAWI hosts its first Crisis Corps Volunteers, requested by the government and UNICEF to address cholera outbreaks and assist with prevention.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2004 | March

GHANA: Crisis Corps Volunteers help launch HIV/AIDS education initiative.

2004 | November

ZAMBIA: Volunteers funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) work with neighborhood health committees and ministry of health.

2004 | December

INDIAN OCEAN: A 9.1 magnitude earthquake generates a tsunami, devastating communities in a number of nations. Scores of RPCVs serve with Crisis Corps in Thailand and Sri Lanka to assist with relief measures.

Map: Wikimedia Commons

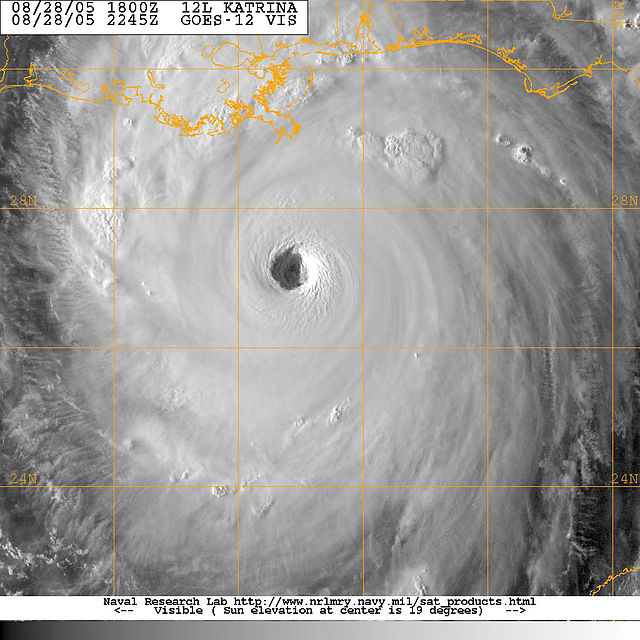

2005 | August

U.S. GULF COAST, particularly the New Orleans area, bears the brunt of Hurricane Katrina. For the first time, Crisis Corps Volunteers are asked to serve domestically; they partner with FEMA on relief work in hurricane-ravaged areas. While Peace Corps is an international organization, Director Gaddi Vasquez notes, “Today, as many of our fellow Americans are suffering tremendous hardship right here at home, we believe it is imperative to respond.” Volunteers take on 30-day assignments. Projects range from opening a disaster recovery center in the Lower 9th Ward to distributing food and water to displaced families. In total, 272 Volunteers serve 9,323 days and contribute 74,584 hours of service.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2005 | October

CENTRAL AMERICA hit by Hurricane Stan. In Guatemala, Crisis Corps Volunteers assist with reconstruction.

Photo: NASA

2007 | October

TULANE UNIVERSITY: Crisis Corps International Scholars Program launched; it pairs work on a master’s degree with a Crisis Corps assignment.

2007 | November

PEACE CORPS RESPONSE is the new name for Crisis Corps. Peace Corps Director Ron Tschetter says the new name better captures what Volunteers do, addressing critical needs in health, education, and technology — along with serving in disaster situations.

Photo: Peace Corps

2008 | October

LIBERIA: Response Volunteers lead the return of the Peace Corps, after an absence of nearly two decades. They work in education to revitalize training, schools, libraries, and more; and in health training. Their swearing-in ceremony is attended by Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, Peace Corps Director Ron Tschetter, and U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield.

Photo: Peace Corps

2010 | January

HAITI struck by 7.0 magnitude earthquake and scores of aftershocks. Some 250,000 people die;

1.5 million are left homeless, without access to clean water or food. Many hospitals are destroyed. Response Volunteers serve as part of global relief efforts.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2012 | January

JAMAICA: Dorothy Burrill, 73, is first Response Volunteer who hasn’t already served in the Peace Corps. Eligibility now open to those with 10 years’ work experience and language skills.

2012 | March

GLOBAL HEALTH SERVICE PARTNERSHIP launched in collaboration with PEPFAR and Global Health Service Corps. The goal: address shortages of health professionals by investing in capacity building and support for existing medical and nursing education programs in African nations of Tanzania, Malawi, and Uganda.

2012 | October

SOUTH AFRICA: Response Volunteer Meisha Robinson and 12 Peace Corps South Africa Volunteers collaborate with Special Olympics staff and community members to organize the inaugural Special Olympics Africa Unity Cup. Fifteen nations’ soccer teams compete.

Photo: Special Olympics

2013 | November

THE PHILIPPINES pummeled by Super Typhoon Yolanda, killing thousands. Response Volunteers assist in affected areas.

2014 | September

COMOROS: Peace Corps announces it is returning, after a decade’s absence, with 10 Response Volunteers leading the way — to teach English and support environmental protection.

Photo: Peace Corps

2015 | March to April

MICRONESIA hammered by Typhoon Maysak. Response Volunteers assist with reconstruction.

2015 | December

PARTNERSHIPS: Peace Corps Response and IBM Corporate Service team up to engage highly skilled professionals to work collaboratively. Response also leverages partnerships with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Rotary International.

2019

ADVANCING HEALTH PROFESSIONALS program launched in five countries: Eswatini, Liberia, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. The program succeeds the Global Health Service Partnership and assigns Volunteers to nonclinical, specialized assignments that enhance the quality of healthcare in resource-limited areas, improving healthcare education and strengthening health systems at a societal level.

Photo: Peace Corps

2020 | March

GLOBAL: COVID-19 leads Peace Corps to evacuate all Volunteers and Response Volunteers from around the world.

2021 | May

UNITED STATES: Response Volunteers begin serving with FEMA community vaccination centers to battle the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Photo: Peace Corps

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleIn 2019, Peace Corps Response launched Advancing Health Professionals. Then the pandemic hit. see more

In 2019, Peace Corps Response launched the Advancing Health Professionals program. Then the pandemic hit.

By Sarah Steindl

Advancing Health Professionals (AHP) is designed to strengthen health systems in five countries. Photo courtesy Peace Corps

Bolstering public health in communities where Volunteers serve has been part of Peace Corps since the beginning. In 2019, under the aegis of Peace Corps Response, the agency launched Advancing Health Professionals (AHP), a refocused effort to train healthcare professionals and improve healthcare systems in the African nations of Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Liberia, and Eswatini. The program came online just months before COVID-19 swept the globe. Healthcare disparities were exacerbated, scarce resources further stretched.

The value of AHP — to improve healthcare education and strengthen health systems at a societal level — became even more pronounced, notes program manager Dawn Childs. “The pandemic highlighted the need to help the countries grow their programs,” she says, “so that they can educate more nurses, pharmacists, and more physicians.” Yet the pandemic also interrupted the AHP Volunteers’ in-person work, as they had to be evacuated from their sites around the globe.

A training session with Advancing Health Professionals, Malawi — a program Towela Nyika has managed since 2018. Courtesy Peace Corps Malawi

For Volunteers with AHP, there is no age limit, nor is prior Peace Corps experience required. AHP staffs non-clinical assignments with individuals who have backgrounds in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, mental health, pre-clinical education, healthcare administration, healthcare services delivery, and midwifery.

“There’s going to be another pandemic in our lifetime. We’re one connected world. So we’re going to have to be a global program, strengthening health systems.”

— Anna VecchiChilds has worked with the Peace Corps agency for a short time, but she brings extensive experience in Africa with the CDC and the U.S. military. One member of the AHP team who brings experience as a Volunteer is Anna Vecchi, an outreach specialist who served in Malawi 2015–17. After that, she served as national malaria coordinator for Peace Corps Response in Malawi 2017–18.

“It’s the transfer of knowledge that the AHP program highlights,” Vecchi says. Along with bringing technical skills, Volunteers lean hard on their abilities as communicators, teachers, and students — learning about communities where they’re serving and how local healthcare systems work.

More broadly, Vecchi says, “It’s not enough to think in terms of public health. From now on we need to think in terms of global health. There’s going to be another pandemic in our lifetime. We’re one connected world. So we’re going to have to be a global program, strengthening health systems.”

This is part of a series of stories on and by Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleInsights from the program manager for Advancing Health Professionals in Malawi see more

Towela Nyika

Peace Corps Staff in Malawi (2013–present)

As told to Emi Krishnamurthy

I began with the Peace Corps in 2013 with the Global Health Service Partnership, a public-private partnership to place healthcare professionals as adjunct faculty in medical and nursing schools. When that program ended in 2018, I helped start Advancing Health Professionals, which combines volunteer work with strengthening health systems. In Malawi, we bring in highly skilled health professionals from the U.S. who work with institutions of higher learning, training the next generation of health workers. We focus on bridging health theory into practice, and promoting skills and quality health services.

Healthcare is a huge need in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In Malawi, our few healthcare workers are always overworked and overwhelmed. Now we have COVID-19 in the mix. AHP enables us to work with institutions training healthcare workers — nurses, pharmacists, medical doctors, lab technicians — and to develop skill sets to offer better services to the population.

Towela Nyika, center front — program manager for the Advancing Health Professionals program in Malawi. Photo courtesy Peace Corps Malawi

In colleges, COVID-19 has presented a challenge to how classes operate. Volunteers have helped students find research portals and download videos. Internet access is slow, so pre-downloaded material is like gold. Institutions are embracing technology, but students may not be able to afford laptops or don’t have enough data to join a class online. We’re discussing creation of a digital library. If a student has a smartphone, they might be able to tap into hundreds of thousands of videos, PDFs, research papers, and other resources without needing internet access.

When Volunteers leave, they often say, “I have learned much more than I taught.” There’s a lot to learn professionally, culturally, and socially. Volunteers work in an environment with limited resources; they have to get creative to deliver quality lessons. They make lifelong friendships. I can’t wait for the Volunteers to come back. I would love to see AHP grow. Ultimately, we are trying to achieve health for all.

Students work with a Peace Corps Response Volunteer in the Advancing Health Professionals program. The goal: health for all. Photo courtesy Peace Corps Malawi

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleLearning and teaching through the Advancing Health Professionals program see more

Dallas Smith

Peace Corps Volunteer in Cambodia (2017–19) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Malawi (2019–20)

As told to Emi Krishnamurthy

Photo: Baobab tree — used for food and medicine. Photo by Dallas Smith

While earning my Doctor of Pharmacy in the States, I spent a month in India learning about what’s known as traditional and complementary medicine. Then, in Cambodia, I saw it utilized to heal people, using local culture and expertise. I brought that perspective into Malawi, but I took it one step further: I know it works, but why? How do we make it better? What are the side effects? How do we make it more clinically relevant so that we can employ it in a better way?

In Malawi I learned from experts knowledge that has been passed along generations. My advice for Response Volunteers is to be a humble and open learner.

In Malawi I learned from experts knowledge that has been passed along generations. My advice for Response Volunteers is to be a humble and open learner. With that in mind, the Advancing Health Professionals program provides a venue for pharmacists to pass along their knowledge, skills, resources, and connections to countries that are developing the pharmacy profession — especially the clinical aspect.

Students in a medicinal garden in Malawi. Photo by Dallas Smith

At the beginning of the pandemic, the University of Malawi College of Medicine had a big hand-sanitizer production project to prepare for when COVID might hit Malawi. When we got evacuated, the College of Medicine transitioned to online learning, and I’ve been teaching virtually since then.

This was hard for a lot of health professionals; it felt like we were abandoning our colleagues. That feeling drove me to serve where I could; June to December 2020, we were in Arlington, Virginia, and I started volunteering with the Virginia Medical Reserve Corps at COVID-19 testing sites. When the vaccine came out, I helped with rollout as a senior point of dispensing (POD) director.

The coolest part was working with such a diverse crew of community members to tackle both the testing and the vaccination with limited resources. We set up sites at gymnasiums, community centers, park benches, and homeless shelters. We had retired schoolteachers, retired nurses; we had actors, pharmacists, physicians, a dental hygienist. We were all working our butts off to end the pandemic. I can’t tell you how many amazing 65-year-old retired nurses volunteered their time to vaccinate for 12 hours a day, even when they were at risk. They wanted to end this pandemic. They weren’t going to let the possibility of contracting this disease stop them from their duty to health equity.

I also got to work with half a dozen other RPCVs. We used some of the languages we picked up from our Peace Corps services. Now I am working in Atlanta with the Epidemic Intelligence Service, which is a CDC disease detective program.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleShe brought literacy expertise to work in Belize. And has volunteered with FEMA to combat COVID-19. see more

Judith Jones

Peace Corps Response

Volunteer in Belize (2018–20) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer with FEMA in Oregon, United States (2021)

As told to Sarah Steindl

Photo: Teacher and student at work in Belize. Photo courtesy Judith Jones

My Peace Corps journey was a little bit different. I originally applied to be a two-year Volunteer in Jamaica, and I got rejected for medical reasons. I appealed, and I lost that decision. I was devastated because this was something that I really wanted to do in my retirement. Then out of the blue, a month later, a friend who works for USAID wrote me about the literacy support specialist position in Belize for Peace Corps Response: “I think you’d like this.” I looked at it and thought, My gosh, this was written for me! I’ve taught children and adults for 30 years, worked as an ESL teacher and literacy coach. I applied at the beginning of February 2019. They told me toward the end of April that I was going, with five weeks to get ready.

In Belize we worked with the Ministry of Education. We worked with second-grade teachers to help develop their skills in teaching reading. Belize is a place where they are still using very traditional teaching methods. We had to meet them where they were at. We gave them workshops and courses, and we went on-site in classrooms to help implement strategies: working with a small group of students, designing activities to improve reading levels.

We found kids in second grade who couldn’t spell their name, didn’t know the complete alphabet, the sounds that letters make, or how to spell simple words. By second grade, most children should know these things. But classrooms don’t have books. I wanted to get more books in the classroom, but it was important that the teachers take on those projects. My country director, Tracey Hébert-Seck, was a big proponent of not doing things for them, but doing things with them, and teaching them to do it on their own.

Literacy at the forefront — and Judith Jones in the background, observing a teacher work with her intervention group of students in Belize. Photo courtesy Judith Jones

I think there need to be more 50-plus Volunteers and staff. There need to be more Black and brown Volunteers and staff, more variety in sexuality and gender. Peace Corps needs to reflect America. I don’t see that in recruiting. I don’t see that in staff. It’s hard to get into Peace Corps if you’re 50-plus or 60-plus. To go through the craziness of the medical clearance process, you have to spend so much money — so how are you going to get Volunteers from a lower socioeconomic area? It really needs to be made easier and more diverse. We should be able to participate.

With Response, I got to do something closer to the work that I love doing. I want to continue to put literacy at the forefront of education. Literacy will improve countries, economies, and social situations.

With Response, I got to do something closer to the work that I love doing. I want to continue to put literacy at the forefront of education. Literacy will improve countries, economies, and social situations.

I enjoy doing this job I’m in right now, supporting the vaccination effort with FEMA. The Oregon Health Authority has been a fantastic counterpart. And it’s interesting working with all these young people. But that’s very different from what Peace Corps Response usually is; typically Volunteers are more mature and used to working. We learned from each other. It was invaluable.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleHaving to be evacuated in March hasn’t put an end to Annie Eng’s work with Georgia. see more

Annie Eng

Peace Corps Volunteer in Georgia (2020) | Peace Corps Virtual Service Pilot Program (2020–21)

As told to Sarah Steindl

Illustration courtesy Work by For Better Future, a Georgian NGO, whose projects include supporting women entrepreneurs.

I had a friend in Ukraine who was a two-year Volunteer, and seeing all he was doing there inspired me. One day, I was browsing and saw Peace Corps Response Service. I took a one-year leave of absence from my job in New York, and I arrived in Georgia in February 2020. I went through orientation, then headed to work with the Khashuri Municipality, about 80 miles west of Tbilisi. I fell in love with the country — so much to explore and learn.

I worked as an organizational development and capacity building specialist, creating and executing training sessions. I focused on business acumen, public speaking, credit proposal writing, public relations, and some technologies that could help drive efficiency. I spent that first month mostly scoping out a baseline; a big part of capacity building is understanding where everyone is, their skill sets, and what we need to bring forward. After one month we were evacuated.

My Georgian family tried to do so much to help me get plugged in to the community. On International Women’s Day, my host mom took me to a supra, a traditional Georgian dinner filled with food, wine, and dancing. Almost every woman from the community was there. That was a week before we had to leave.

When Peace Corps launched the Virtual Service Pilot last fall, I saw it as an innovative way to continue doing what I hope to do: creating a bridge between communities. I worked with For Better Future, a Georgian NGO focused on supporting internally displaced person settlements. We worked on content and public relations strategies across different platforms. This kind of work is especially important now, because the world is rapidly evolving into something more global and intertwined; having a level of understanding across different cultures is crucial. I’m volunteering in the VSP program again, working with the Tkibuli District Development Fund on community engagement strategy and initiatives. We’re all continuing to learn. And, as the pandemic and evacuation reminds us, you can never be fully prepared for things that come your way.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleBuilding environmentally and economically sustainable projects see more

Hilliard Hicks

Peace Corps Volunteer in South Africa (2014–16) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in the Philippines (2019–20)

By Hilliard Hicks

Photo: Marine biology students conduct quadrat seagrass surveys in the Philippines. Courtesy Hillard Hicks

In 2020 the world was thrust into a pandemic, which caused more than 7,000 Peace Corps Volunteers to suddenly return home from their adopted communities around the world. I was one of them.

During my first Peace Corps assignment, I served as an education Volunteer in South Africa. After service, I went to graduate school at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, studying marine biodiversity and conservation, and earned a master’s degree in June 2019. I boarded a plane to the Philippines later that year for a Peace Corps Response assignment: an aquatic resource management specialist, eager to be a champion of the marine environment in a community interested in sharing ideas about conservation. It was exciting — and it felt like the right time to venture out of my comfort zone; I was sure I’d stick out as the sole African American ecologist.

My assigned site was Leyte, on a bay frequently visited by whale sharks. I was tasked with teaching at a small technical university with a few hundred students. This remote campus focuses academic curriculum on marine biology, life sciences, and agriculture. It also provides the community with organic vegetables, compost, seaweed — and, previously, fish, at a discounted rate. The campus boasts nine fish ponds, which range in size from a football field to a basketball court. The ponds are sprinkled with nipa palms, one type of mangrove, and some other species of red mangroves. Egrets line the banks, hungrily looking for mussels or small fish to eat.

The ponds were certainly beautiful, but had deteriorated after years of neglect. At a marine science school, it’s critical that students get their hands dirty and learn about aquaculture, an important part of the economy in the Philippines. We decided it was necessary to rehabilitate the ponds to improve hands-on learning for the students and to increase the number of fish available for the community to buy.

Marine biology students in Southern Leyte, Philippines, are helping remove debris from milkfish ponds. This was part of a rehabilitation project to restore the ponds for aquaculture. Photo by Hilliard Hicks

The first problem we ran into was a need to install a submersible pump that would allow ponds to fill when the tide was too low. We received a Peace Corps Partnership Program grant from a generous donor and were able to purchase the parts and equipment we needed. In the Peace Corps, nothing gets done without the help of counterparts we work with. I don’t think my counterpart anticipated labor-intensive work when this project was proposed, but we ended up carrying about 400 feet of PVC pipe to the ponds, which were about 100 yards from the delivery site. Digging out trenches to lay pipes in 80 percent humidity and stifling temperatures was exhausting, but we got it done.

One of the biggest challenges was that high tide would cause the adjacent canal to fill partially, causing garbage to clog the channel. After building screened gates at each entrance, we were able to prevent new debris from entering the ponds. Then we had to clean the remaining garbage from the area. We enlisted the marine biology students to help, beginning work before dawn to avoid the midday heat. Every step we took, our feet sunk about a foot in the mud, so we laid boards and stiff palm leaves to make impromptu bridges and serve as handholds.

Marine biology students conduct quadrat seagrass surveys in Southern Leyte, Philippines. Photo by Hilliard Hicks

Once we cleared the ponds, built the gates, and laid the pipe, it was time to test the system. It was attached to a pump that had been sitting for five years. My counterpart was adamant that our pump worked. But one of the battery capacitors was defective. The entire pump had to be taken apart and rebuilt. Retrofitting a submersible pump and building a cage around it was no easy feat, but we had to prevent trash from being sucked in.

After months of hard work, everything was in order and we finally filled the ponds. About a week later, I was evacuated.

After months of hard work, everything was in order and we finally filled the ponds. We stocked the ponds with milkfish, locally called bangus. This bony fish lives in brackish water and is a popular fish eaten in the Philippines. Bangus is usually farmed in ponds, but can be grown in open water. In our ponds, it did extremely well. About a week after we stocked the ponds, I was evacuated.

Back in the United States, I began seeing posts on Facebook about the university selling fish from our hard-won fish pond. Knowing the pond we rehabilitated during my service was increasing their bangus productivity for the community — especially during the pandemic — was a gift. My counterpart and I, along with the hardworking marine biology students, helped the people in the community.

Even though the pandemic cut my service short, Peace Corps Response allowed me to make a long-term impact during a short-term assignment. I’m grateful for that. And, when the world returns to normal, I’ll do it again.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

Hilliard Hicks works with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fisheries, increasing awareness of coral reef ecosystems. His story originally appeared at peacecorps.gov.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleThe complex work of HIV/AIDS prevention in St. Lucia see more

Yemi Oshodi

Peace Corps Volunteer in Swaziland (2003–05) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in St. Lucia (2011–12) | Peace Corps Staff (2011 to present)

As told to Sarah Steindl

Photo: Yemi Oshodi in April 2021, speaking to communities in the Eastern Caribbean after the eruption of La Soufrière, on the main island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

Go back a decade: I had about eight years of experience in public health — advocacy, international policy, HIV/AIDS work. I wanted to give back in a similar way that I had as a Volunteer in Swaziland 2003–05. I looked into Peace Corps Response and took a position in St. Lucia, as project development coordinator with St. Lucia Planned Parenthood Association. I co-led the men’s health initiative, focused on HIV prevention and mitigation. We worked with police officers, firemen, and correctional officers, training them so they could train other men on HIV prevention and other men’s health issues. The training also explored social constructs such as masculinity and machismo.

The workshop was highlighted in a local television news program. And the training opened the door to numerous other opportunities to work on HIV prevention. One project involved visiting the crowded bus ranks where we would spend hours engaging mini-bus drivers about HIV/AIDS prevention. I appreciated the authentic conversations and seeing people’s eyes light up when they grasped new concepts. Through other projects, we also addressed the unique HIV-prevention needs in St. Lucia for members of the LGBTQ community.

In St. Lucia, “one project involved visiting the crowded bus ranks, where we would spend hours engaging mini-bus drivers about HIV/AIDS prevention,” says Yemi Oshodi. Photo courtesy Yemi Oshodi

Response work is a collaboration between the Peace Corps and the host partner organization; it’s not about just bringing people in to do the job. It’s about a transfer of knowledge, skills, and collaboration. I saw the job description — tasks and expectations — and I understood quickly that I couldn’t do it on my own. It was something I had to do with my counterpart, Patricia Modeste, who was awesome. She was so knowledgeable about sexual and reproductive health. And she helped reaffirm that public health work can be engaging — you can make it hilarious. During our weeklong training, we designed a session that had a talk-show format, because in St. Lucia at that time, talk shows like Jerry Springer were quite popular. So in our talk show we educated people on sexual and reproductive health using the drama and even the bit of fun mayhem that comes with being in a television show.

It’s not about just bringing people in to do the job. It’s about a transfer of knowledge, skills, and collaboration. I saw the job description — tasks and expectations — and I understood quickly that I couldn’t do it on my own.

I’ve worked with the agency for the past eight years in Washington, D.C., in Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), and currently in Guyana. I’m timing out in May 2022, so I’ve been thinking about a question a lot of Volunteers face at the end of their service: What is my unfinished business? For me, it’s often interpersonal. Have I practiced empathy enough? Have I practiced humility enough? Have I learned enough from those around me? And have I grown enough in this context here in Guyana, where I am working as director of programming and training? Have I challenged people enough to be supportive, empathetic leaders and managers? Because you can never do that enough. Have I worked to equip others to be able to finish the work we started together — specifically my local colleagues? Because at the end of the day, this is their country. It’s their legacy, too, right? A good legacy, for me, as a Peace Corps Volunteer and now Peace Corps staff, is leaving a place better, and even more equipped than I found it.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an article“It would be wonderful if the world didn’t need a Peace Corps.” see more

Miguelina Cuevas-Post

Peace Corps Volunteer in Jamaica (1976–78) and Belize (2011–13) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Jamaica (2016–17) and Belize (2017)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Students in a Jamaican school where Volunteer Miguelina Cuevas-Post served. Courtesy Miguelina Cuevas-Post

I come from a family that is multiethnic and multicultural, so an appreciation of different cultures was ingrained in me. My husband, Kenneth Post, and I both served two-year terms in Jamaica in the ’70s — that’s how we met. We got married there, and our oldest daughter, Tina, was born while we were serving. Ken and I also served in Belize 2011–13. My youngest daughter, Rachel, decided to serve as a Response Volunteer in the Republic of Georgia 2015–16. I returned to both Jamaica and Belize as a Response Volunteer in 2016–17. And my husband’s aunt did Peace Corps in Africa at age 65. So obviously, Peace Corps has had a great presence in my life!

My initial host mother in Jamaica was just around the block from Hope Road, where Bob Marley lived. We would walk by his house frequently. We were in Jamaica when he was shot in December 1976. He survived, but that was a tense and harrowing time.

During my original service, if we needed to communicate with a Peace Corps office for any reason, we would go into Port Maria and send a telegram. There was one public telephone and it wasn’t working half the time. Today, technology has made the world a lot smaller, and because of those advances, countries’ needs have changed. Retirement wasn’t meant for me, so after working for years as a school administrator, having the chance to return to Jamaica as a Response Volunteer 40 years after my original service was a great opportunity.

The city of Kingston, which was just a little bigger than a village, is now exponentially larger. Rural areas have new roads and businesses. There are more high-level education and leadership needs, hence Peace Corps Response.

Artist at work: “Rastas living in the Kingston dump who create the most beautiful art out of recycled aluminum.” Photo by Miguelina Cuevas-Post

I have a specific memory of a group of Rastas living in the Kingston dump who create the most beautiful art out of recycled aluminum. This project began with the help of a returned Volunteer who comes back periodically to provide support. We were there trying to gather information to share with the JN Foundation, the agency with which I worked. We spent a day watching the men work, and at the end, I purchased a piece that I saw made from start to finish.

“We saw this piece created, from the melting of the recycled aluminum, to the pouring of the melted metal (casting), removal once set, and buffing,” writes Miguelina Cuevas-Post. “I purchased the piece for one of my daughters.” Photo by Miguelina Cuevas-Post

Belize’s education sector, which was the sector I originally worked in as a Volunteer a decade ago, had closed when I left. But a few years later, when I returned as a Response Volunteer, it reopened and I was asked to return. Response service is very specific and targeted. Projects have to be completed within the time you are given, and you must produce tangible evidence of impact. We were in the Peace Corps office working seven days a week. We understood that the successful reintroduction of an education sector in the country depended on our results. I am incredibly lucky and grateful to have been able to return to both Jamaica and Belize to reconnect with villages where I lived and see their progress.

Ideally, it would be wonderful if the world didn’t need a Peace Corps, but that’s not the reality.

Ideally, it would be wonderful if the world didn’t need a Peace Corps, but that’s not the reality. I also feel like there’s another Peace Corps life in me. Maybe not Belize or Jamaica, but I hope that before I get too much older, I will be able to serve again.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleA Haitian American Volunteer navigating the uncertainties of a time of crisis see more

Carlos Jean-Baptiste

Peace Corps Volunteer in Kenya (2006–08) and Zambia (2008–09) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Haiti (2010)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Haiti in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake: Carlos Jean-Baptiste, in blue shirt, assisting with relief. Courtesy Carlos Jean-Baptiste

I identify as a first-generation Haitian American, born of an immigrant mother. I grew up in a community where my grade school was 50 percent first-generation American, so I experienced the world through these relationships. I was always aware of how big the world is. Peace Corps was a path to experience it firsthand, and it helped me understand the complexity of identities and how we have a responsibility to parse those identities — our own and those of people we live and work with.

When I arrived in Kenya as a Volunteer, I was petrified. But when my host father met me, he embraced me, and he said, “Today, my son, you were born in Africa, and your name is Makau.” To be embraced by a community, by someone who doesn’t know you, and to immediately feel a sense of belonging — that’s a very significant feeling.

While I was in Kenya, I was a behavior change communicator for Deaf audiences. It was a pilot program, and most of us who went were artists and graphic designers. The idea of being able to create visual media to communicate behavior change was promising and exciting. It was an amazing experience to get the chance to work with the Deaf community — people who see themselves as their own tribe, but who all represent different ethnic groups within Kenya.

I was in service for about 18 months before Peace Corps suspended the program due to civil unrest following the 2007 elections. Four of us went to Zambia and met with the country director. She asked if we were interested in doing a pilot there, which ended up being a great way to build something new and carry on from our previous service.

The earthquake hit Haiti in January 2010. I was working in Ethiopia at the time. I immediately started trying to find ways to help.

The earthquake hit Haiti in January 2010. I was working in Ethiopia at the time. I immediately started trying to find ways to help. I did some fundraising, but I was ultimately able to volunteer with Peace Corps Response, working with USAID. That was my first time in Haiti; it was unfortunate that it took the earthquake to get me there.

The program was put together as quickly as possible, trying to find the right skill sets to be most effective. It was a disaster response situation: I came in from the airport and they sat me at a table and told me to read all these documents and explain what I was going to do. Those first hours were cathartic. It’s all epiphany, it’s all learning — what I know, what I don’t know, how to move forward. Not knowing everything is fine. But knowing people is an expertise as well — how to read cues. Leaning on experiences I had from Kenya and Zambia and Ethiopia, I knew that if you don’t ask the right question, or don’t ask it the right way, you’re not going to get the answer you really want. Sometimes people are going to tell you what they think you want to hear rather than what you need to know.

What I did was fill gaps for a long time: I would be an informal interpreter in the field; then I worked as the liaison to the United Nations Clusters. Any given day, you could be working on something totally different, responding to immediate needs. We were facilitating specific parts in the recovery via monitoring and evaluation, recommendations about what people should do. I was able to work on a project at its inception and then work in a different agency to develop and implement it. So I got the chance to see the fruits of my work in a way that a lot of Volunteers don’t.

In terms of identity, in Haiti I could be Haitian — but also American. I could speak Kreyòl in a really comfortable way, but also speak English. It was the first time that everyone around me was speaking the language that I grew up speaking. How many people have that moment where you swear you’re an expert, and then you’re confronted with however much you really know — or don’t? It’s incredibly humbling — but not humiliating.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWithin 48 hours she was on a plane, headed to serve in Katrina relief efforts. see more

Priscilla Goldfarb

Peace Corps Volunteer in Uganda (1965–67) | Crisis Corps Volunteer in Alabama, United States (2005)

By Joshua Berman

From the Winter 2010 edition of WorldView

Photo: Priscilla Goldfarb serving as a Crisis Corps Volunteer with FEMA after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Courtesy Priscilla Goldfarb

Priscilla Goldfarb, a longtime nonprofit executive and former National Peace Corps Association board member, had a 40-year gap between her Peace Corps service in Uganda in the mid-1960s and her first Response assignment. Two weeks after Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc across the Gulf Coast — and not long after she retired — Goldfarb received an email looking for volunteers. For years she had wanted to serve with Crisis Corps, but she had never been able to get away from her job and family. She responded immediately.

Katrina at 6 p.m. on August 28, 2005. Satellite image provided by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey

“After a flurry of paperwork exchanges and telephone interviews,” she says, “I found myself in about 48 hours headed to Orlando, Florida, for training.”

This was an exceptional turnaround; at the time, acceptance, medical clearance, and placement typically took around three months.

Goldfarb received an intensive 72-hour training from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, then was handed a FEMA hat and T-shirt and sent into the field. She was assigned with a buddy to a small town about an hour north of Mobile, Alabama, close to the Mississippi border. They were part of USA-1, the first-ever domestic deployment of Crisis Corps. More than 270 fellow Volunteers joined in the Katrina relief effort, also making it the largest deployment of Crisis Corps Volunteers.

For the first part of her assignment, Goldfarb worked 12-hour days, seven days a week. “It was intense, stressful, and exhausting,” she says. She helped people apply for FEMA assistance, teaching them how to fill out documents and fulfill requirements, and advising people of their rights. Of the 100-plus people Goldfarb served, none had exactly the same issues.

“Some were so traumatized, they wanted simply to talk about their situation and be listened to — and would leave without even filing an application.”

“Some were so traumatized, they wanted simply to talk about their situation and be listened to — and would leave without even filing an application,” she says. “Some had specific and urgent housing and clothing needs. Others needed reimbursement for chainsaws or generators.”

Flexibility and adaptability were part of the assignment. That also jibed with an agency assessment that recommended Peace Corps Response function as “an ‘engine of innovation’ by serving as the Peace Corps’ tool for piloting new programs to expand the agency’s presence and technical depth and to increase overseas service opportunities for talented Americans.”

What about the relevance of her Peace Corps service? “Alabama was about as far away as Uganda had been to this Northern-born and -bred woman,” says Goldfarb. “But there were many similarities to my Peace Corps assignment — the rural lifestyle, agrarian economy, and hidden poverty.” People would greet outsiders with a “mix of reserve, even suspicion, and at the same time, hospitality far beyond one’s means on the part of the people we were there to serve … Familiar, too, was the incredible strength, grace, and dignity of people on a daily basis facing the most adverse of circumstances.”

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

Joshua Berman is a writer and educator based in Colorado. He served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nicaragua 1998–2000. Follow his work at joshuaberman.net.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWorking with women in Bosnia in the aftermath of the civil war — and during 9/11/2001 see more

Teresa Bonner

Peace Corps Volunteer in Lithuania (1996–98) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2001)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Mostar, years after the war. Teresa Bonner arrived there to serve as a Crisis Corps Volunteer in September 2001.

When I became a Peace Corps Volunteer in Lithuania, I expected to go help people. I had a background in design and marketing, and the country was transforming after the breakup of the Soviet Union. But the strongest lessons I came back with were understanding another culture — and that people are the same everywhere in the world: They want to be happy, take care of their family, have fun.

I was assigned to Junior Achievement of Lithuania; I helped with marketing, strategy, and publication of their main textbook. I also had individual clients and advertising agencies. And I helped translate materials with the Missing Persons Family Support Center; women would answer job ads in Germany and never return, probably because they were brought into sex trafficking.

In August 2001, I was recruited into Peace Corps Response Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Bosnian War had been over for six years, but they were still struggling. The organization I was working with helped women adjust to the trauma and loss of war. They were tough women with amazing senses of humor and approaches to life. They had made it through one of the worst civil wars in modern history; all had lost family members, yet they were strong.

“They were tough women with amazing senses of humor and approaches to life,” Teresa Bonner says of her coworkers in Bosnia. “They had made it through one of the worst civil wars in modern history; all had lost family members, yet they were strong.” Photo by Teresa Bonner

I arrived at my site on September 9, 2001. I remember going for a walk the morning of September 11, looking around the city that had been devastated by war. Most buildings were riddled with bullet holes. As I walked by a man fixing his door, I started crying. I truly realized how terrible war is.

When I got back to my apartment, my landlady yelled “Teresa!” She pointed to the TV — the twin towers were coming down.

“I would run in zigzag,” she said, “because you never knew if a sniper would want to shoot you.” She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t looking for sympathy. She was just telling me. So after 9/11, she said, “Now you know what it’s like to have a sniper. You never know.”

I had to skip work for a week. But I knew that I was surrounded by people who had gone through something even more traumatic. A woman I worked with would talk about how, when she was making her way to high school, “I would run in zigzag,” she said, “because you never knew if a sniper would want to shoot you.” She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t looking for sympathy. She was just telling me. So after 9/11, she said, “Now you know what it’s like to have a sniper. You never know.”

I was in a predominantly Muslim community. Part of me wondered, Do they hate me? But it wasn’t like that at all. There was also this, I learned from people in Bosnia: The United States is a superpower, but if this can happen to America, who’s safe? I had some powerful conversations with the women I worked with about that.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleOne of those moments I thought, We’re doing something right. see more

Lily Asrat

Peace Corps Volunteer in Namibia (1996–98) | Crisis Corps Volunteer in Guinea (2000) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Eastern Caribbean–St. Lucia (2006)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Reviewing HIV records in St. Lucia: Lily Asrat working at the National AIDS Program Secretariat. Courtesy Lily Asrat

I’m Ethiopian American, and my parents exposed me to a lot of travel early on; they essentially raised me to be a global citizen. I understood that there’s so much out there in the world, and that there isn’t just one way of being. I saw Peace Corps as a continuation of this trajectory that started from childhood.

For my first Peace Corps service, I went to Namibia, which had just achieved freedom from South African colonial rule and the apartheid system. It was like coming to the United States immediately following desegregation: a lot of post-conflict tensions, a society coming to terms with racial healing, and people trying to coexist in a new landscape. It was a difficult time because there were still vestiges of armed struggle. But it was also a hopeful time because the majority of the population — who had been brutalized and subjugated — were feeling and seeing hope, freedom, and access to information and education.

I was a teacher trainer on a collaboration with USAID. The country was moving away from an education system based on apartheid — separate and unequal. The new Ministry of Education charted a path to develop new curricula that would be accessible to the whole population of Namibia.

While I was training teachers, my community was faced with a growing HIV epidemic. There was no treatment or testing accessible. There was a lot of stigma; it was considered a disease of gay men in the Western world, so people didn’t speak about it. But there were people sick and dying — a lot of teachers whose funerals I attended. My host sister died from HIV. It was devastating. That was the impetus for me to go down the track of public health. I realized that the real threat to the education system — and to the majority of the young, viable, productive populations of the country — was HIV. I got involved in doing HIV prevention work and education, collecting teaching aids and materials that I could share within the community.

Over a decade later, I found myself once again in Namibia working for another organization and witnessed significant improvements in access to treatment. At one clinic there was an HIV-positive woman seeing her doctor; she gave me her baby to hold. The baby was HIV negative. They had the knowledge and treatment available to provide the mother with antiretroviral therapy so she could avoid transmitting HIV to the baby during birth and breastfeeding. It was one of those moments in my life when I thought, We’re doing something right.

They had the knowledge and treatment available to provide the mother with antiretroviral therapy so she could avoid transmitting HIV to the baby during birth and breastfeeding. It was one of those moments in my life when I thought, We’re doing something right.

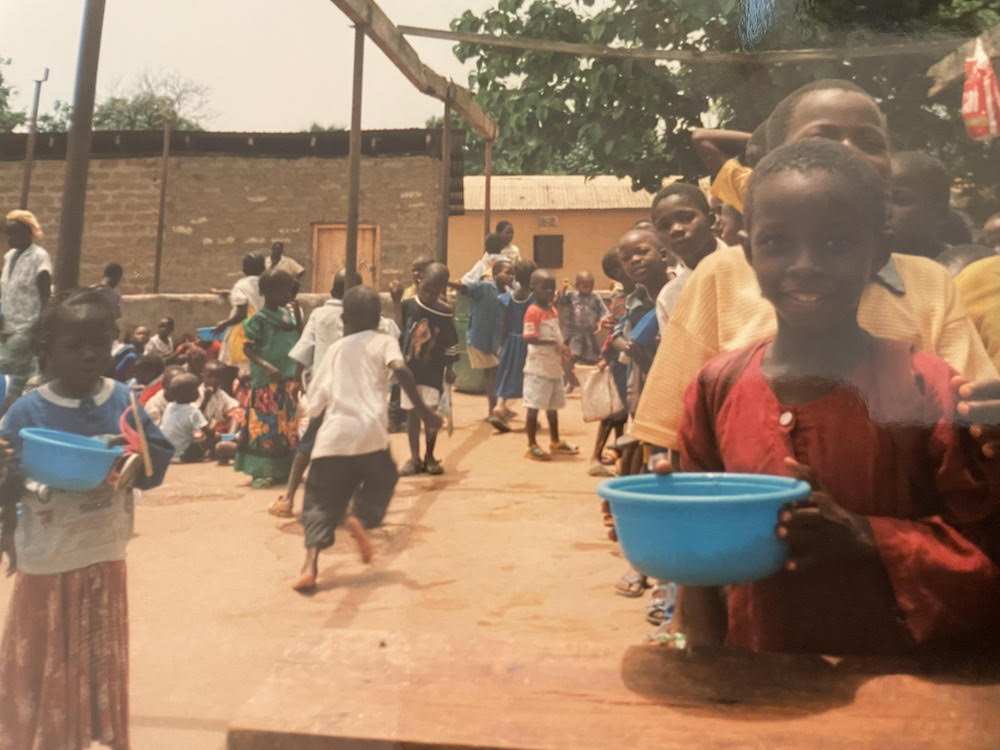

In 2000, I went to Guinea as a Crisis Corps Volunteer seconded to the International Rescue Committee, which was responsible for providing housing, nutrition, education, and psychosocial support for Liberian and Sierra Leonean refugees. Speaking French was one key criteria; the other was being a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer — able to hit the ground running. Being professional and flexible, able to develop relationships and trust in communities where you’re working — and do anything required with minimal support within hardship areas.

Child refugees in Guinea, where Lily Asrat worked as a Crisis Corps Volunteer seconded to the International Rescue Committee, responsible for providing housing, nutrition, education, and psychosocial support. Photo by Lily Asrat

We had an entire stock of food intended for refugee kids that was stolen overnight. It was clearly an inside job; the people responsible for guarding it had disappeared. Those moments are heartbreaking — but not so uncommon. I sought out immediate solutions, using our resources to help navigate that crisis. While the theft of food intended for refugee children was difficult, we also had many examples of wonderful community engagement such as the groups of women who volunteered on a daily basis to cook, distribute, and clean up. They put time, effort, and love into preparing meals for those kids. They made the hardships worth the effort.

By the time I served as a Response Volunteer in Eastern Caribbean (St. Lucia), I had worked at the CDC for three years, had two more master’s degrees, and I’d been in my doctoral program at U.C. Berkeley, studying public health; it was an opportunity to apply my training and experiences, and give back in a different way. I was placed at the National AIDS Program Secretariat to support strategy and guidance, monitoring and evaluation, and planning and grant writing. I have been very lucky in my career to have worked for three government agencies, several multilaterals, and prestigious academic institutions, but nothing has been as rewarding for me as my three stints as a Volunteer in Namibia, Guinea, and St. Lucia.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.