Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleLessons from the past in how to become a less polarized country once again see more

The U.S. is profoundly polarized — politically, culturally, socially, and economically. That was true during the Gilded Age, too. Halfway between then and now, John F. Kennedy exhorted his fellow Americans, “Ask not what your country can do for you — but what you can do for your country.” So what happened? And how do we turn things around?

From a conversation with Shaylyn Romney Garrett

We Can Do It! image courtesy the National Museum of American History

In The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett offer a sweeping overview of U.S. history from the Gilded Age to the present, tracing how the country was transformed from an “I” society to a “we” society — and then back again.

Earlier this year we caught up with Garrett to talk about this project — which would seem to have a special resonance for the Peace Corps community. The period their data pinpoints as the pinnacle of an American sense of “we are all in this together” is the early 1960s — the same moment that gave birth to the Peace Corps.

Garrett served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Jordan 2009–11. She is a founding contributor at Weave: The Social Fabric Project, founded by David Brooks and housed at the Aspen Institute, and she writes about rebuilding community and connection in a hyper-individualistic world. Here are edited excerpts from her conversation with WorldView editor Steven Boyd Saum.

Origins of The Upswing

A lot of people ask, “How did you come to write a book with Robert Putnam?” In the year 2000, his seminal book Bowling Alone was published. I was taking his seminar on Community in America, his foray into teaching the research behind Bowling Alone. He closes that book with a look at the Progressive Era as a potential template for how to revive communities, associations, and the social capital that he documented as having been lost over the previous half century. I was captivated by the Progressive Era, particularly the settlement movement. Some people are familiar with Jane Addams and Hull House in Chicago. But there were hundreds of settlement houses across the United States. The movement itself — sort of imported from the U.K. — sought to build bridges across lines of difference and, in a sense, offer educated, college-age people a Peace Corps–type experience within the United States. Something like AmeriCorps today.

I wrote an undergraduate thesis advised by Robert Putnam. In the subsequent 20 years, he and I have worked together on multiple projects, the last of which is The Upswing. Bob brought me into the project at a point when he had discovered a remarkable statistical finding that serves as the backbone of the book.

Bowling Alone looked at one aspect of American society — social connectedness, social ties, social cohesion — and asked: What does the trend look like over time? Looking back to roughly the 1960s, Bob saw a marked decline in measures of association, community, and social capital. It was a big finding. But it was a pretty narrow picture. So over the years, Bob started to ask: What was going on with other things — economic inequality, religion?

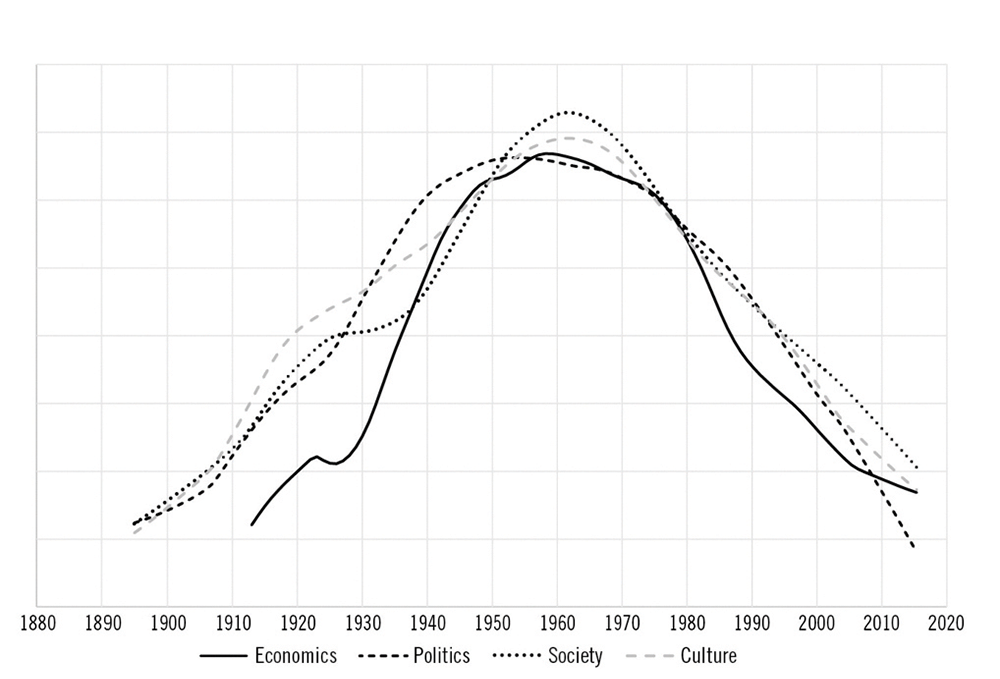

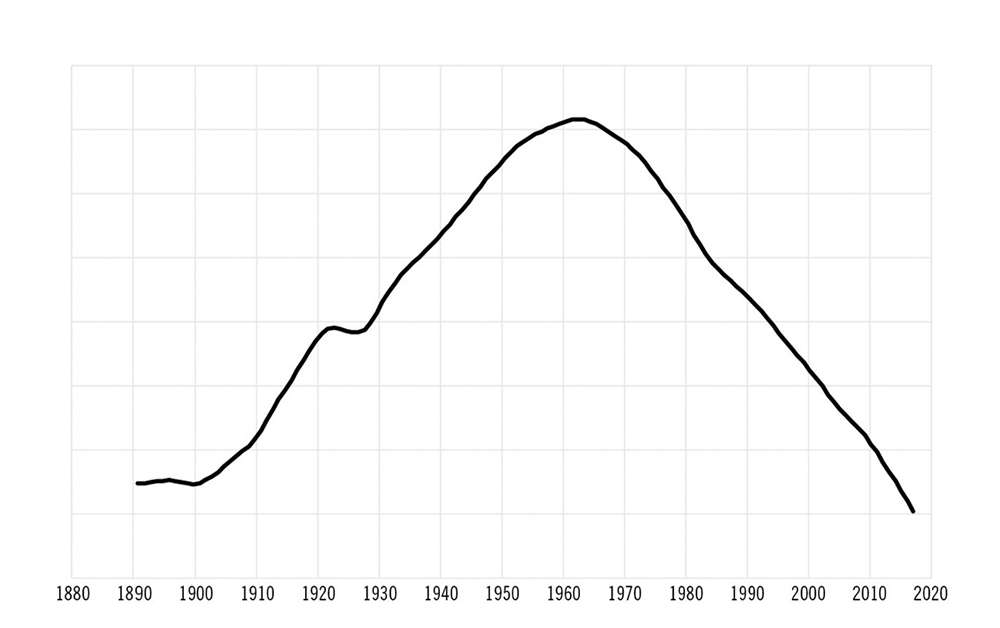

The Upswing incorporates four different metrics. One is social capital, a measure of how connected people are to one another in society. Another is economic inequality. Another is political polarization. The final one is culture — whether we’re more oriented toward a culture of solidarity versus a culture of individualism. It looks at the last century and then some, roughly 1900 to today. When you track those four metrics over this period, they follow the exact same trajectory. For each individual metric, the century-long trends are widely known. But Bob discovered that what scholars had largely thought of as independent phenomena are actually all part of the same century-long meta-trend — a truly striking finding.

In the early 1900s, we were a very unequal, polarized, disconnected, and narcissistic America. Over time, that turned a corner dramatically — into a multifaceted upswing, where all of those measures started moving in a positive direction for six to seven decades. Then, remarkably, in roughly the same five-year period, all of those disparate metrics turned and went the other direction. All that progress we saw over the first two-thirds of the century was reversed, landing us today in a situation remarkably similar to the one in which Americans were living in the late 1800s or early 1900s; historians call it the Gilded Age.

There are different ways you can interpret that upswing/ downturn story. One is to look at the downturn and say, “We’ve had this fall from grace. We need to make America great again. Let’s turn back the clock and go back to this mid-century America that was so wonderful.” A lot of people, particularly of the generation who lived through that period, have been putting forward that narrative. To a certain extent, that narrative culminated in sort of an ugly way with Trump’s MAGA movement.

“If we’ve been in a situation that is, by hard data, measurably identical to the one that we’re living in today — a multifaceted, deep crisis, in all sorts of areas of our society — if we’ve been here before, but we pulled up and out of it, what lessons can we learn from that period that was a downturn that turned into an upswing?”

That’s not really the story Bob or I wanted to tell about these trends. Much more powerful was to ask: “If we’ve been in a situation that is, by hard data, measurably identical to the one that we’re living in today — a multifaceted, deep crisis, in all sorts of areas of our society — if we’ve been here before, but we pulled up and out of it, what lessons can we learn from that period that was a downturn that turned into an upswing?” That becomes a story of when the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era and set us on this upward course that lasted decades. The book looks at the Progressive Era as an instructive period where we can gain inspiration, ideas, and lessons about what to do and what not to do to bring about another upswing.

ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, SOCIAL, AND CULTURAL TRENDS, 1895–2015. Through the early 1960s, all four metrics swing upward: toward equality, bipartisanship, and a greater sense of the common good. The question: How do we move the metrics in that direction again? Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

I-We-I and the origins of the Peace Corps

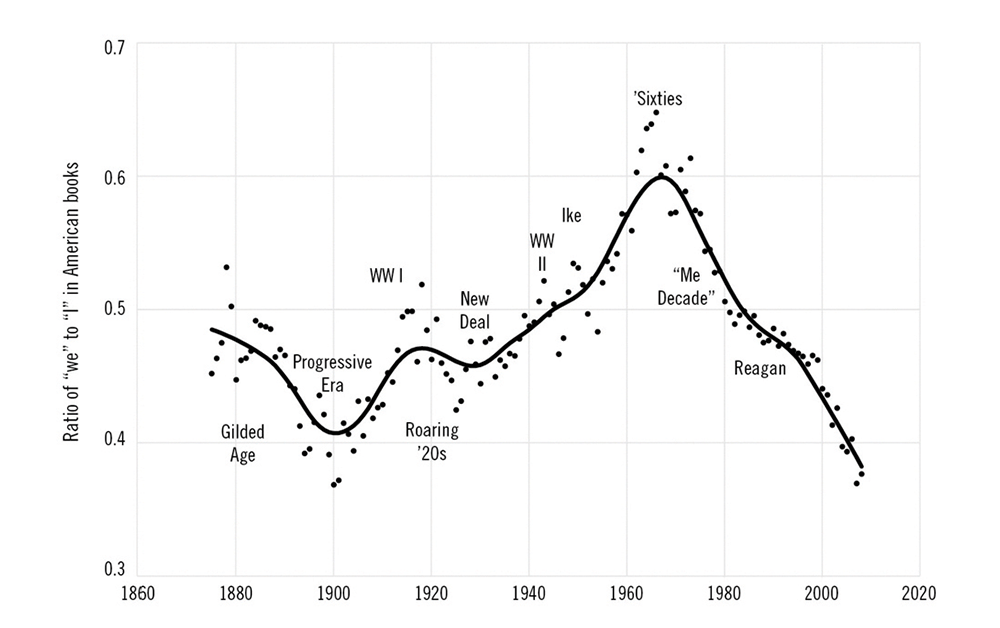

We needed a bit of a shorthand to describe this curve — an inverted U curve: Things were bad, then they went up and got better, then they got bad again. Bob was looking for a way to track cultural trends over time — culture is a notoriously difficult thing to measure statistically — and he discovered Ngram, a database of digitized books in the English language that Google has put together. You can put in different words to track their frequency of use over time. If you put in the word “the” over this 125-year period, it would be a flat line. The incidence of the use of “the” has not changed, which makes sense. However, more culturally tied words are used more or less frequently over time, which gives us a clue about what our culture was more or less focused on during different time periods.

When we track the ratio of the first-person pronoun versus the plural pronoun — “I” and “we” — the curve looks exactly like the curve for economic inequality and polarization. Society was very “I” focused; then “we” as a pronoun became much more common during those first two-thirds of the 20th century. Then it flipped at almost the same time as all of these other curves did, to where “I” became a much more common pronoun. We’re talking about pronouns in all kinds of books, not just academic books: gardening books, cooking books, books about traveling. Mainstream culture books. It’s shocking that it really does look like that, I-we-I.

One interesting point about that moment when the Peace Corps was founded: When we look back to the ’60s we can see two more or less simultaneous phenomena. One was very communalistic, very “we” — the founding of the Peace Corps and the Great Society programs, for example. Then there’s the countercultural movement, which was much more focused on personal rights and freedoms. What’s fascinating about the historical narrative underneath the statistical findings of The Upswing is that you see clearly in the ’60s this moment when the “we” gives way to the “I.”

When John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” we often think it was like reveille for a new era. People at the time really felt it that way … like this was a call for the new and greater heights of “we” that America could move toward, including a more global “we,” which the Peace Corps is part of. However, in retrospect, what felt like reveille for a new era actually ended up being more like “Taps” sounding for an era that was closing.

When John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” we often think it was like reveille for a new era. People at the time really felt it that way. Bob Putnam was physically present at that speech and says he felt it zing throughout his entire body — like this was a call for the new and greater heights of “we” that America could move toward, including a more global “we,” which the Peace Corps is part of.

However, in retrospect, what felt like reveille for a new era actually ended up being more like “Taps” sounding for an era that was closing. We went into the ’60s with all of this energy moving toward “we,” but then there were a number of things that turned that energy into a downward trend toward “I” — such that in the 1970s, you get the “Me” Decade, as Tom Wolfe famously called it, on the heels of this president calling not only for a greater sense of “we” in the sense of civil rights, but also that global sense of what kind of influence America could have in a world that was becoming increasingly connected.

In some ways, that was the heyday of something that is now lost. But that heyday was itself the culmination of something that had been building for 60 to 70 years. Often it’s that first piece of the century that we miss. We don’t realize that America wasn’t always that “we”-focused. Quite the contrary. It took quite a while for us to build up to that apogee in American thinking that spawned things like the Peace Corps.

Only the strong survive.

How did an idea like the Peace Corps get into the atmosphere? What were the decades of work and change, and thinking — and change in language — that got us to that point? That story, again, begins back in the Gilded Age — a time, culturally speaking, that was characterized by social Darwinism. Darwin had articulated a theory about the laws that govern the natural world. Much to his chagrin, people in the social sphere began to take those ideas and say, “Survival of the fittest — this is a great way to organize society.” Essentially, society is one giant competition, there are winners and losers, and the devil take the hindmost. It’s the philosophy that spawned the robber barons and horribly exploitative situations that so many Americans — particularly immigrants and women — found themselves in during the Industrial Revolution.

Onto that scene came reformers who began to question the morality of that as an organizing principle. Jane Addams was one moral voice saying, “Something is not right about the exploitative way that we have organized our society. It’s a betrayal of our founding ideals as Americans. It’s also a betrayal of Christian ideals.”

So we began to ask whether we were really being called upon to take care of our most vulnerable, and not just work for the good of the self. That cultural transformation began to take hold. Moral outrage became the reigning narrative; people began to translate outrage into action. It wasn’t just outrage where we wanted to identify all the bad apples and expel them from society. Jane Addams realized that she had become complicit in systems that were exploitative, so she began to work in innovative ways — at the level of the neighborhood, at the level of the tenement — to try and create change. She was working at the level of individual lives, individual families, trying to help them get out of poverty and exploitative employment relationships. Ultimately, her vision became one of changing policies so that it would become illegal for these things to take place, and more social safety nets would be in place.

A lot of the reformers of the Progressive Era created narratives that we describe as “we” narratives. Over time, these really took hold: in policy, politics, economically, culturally, and socially. But there were also ways these didn’t take hold, particularly around issues of race. The “we” that was being built by Progressives was a very racialized “we.” But at the same time, Black Americans were themselves engaged in a very deep effort to build their own “we,” especially as they moved out of the South during the Great Migration — to build a deeply enmeshed society of mutual aid and care that propelled them forward despite the inequality and exclusion that persisted during the 20th century.

Looking back to this period, you might think, “This was this horribly dark moment. How could people have let it get this bad?” But look around; then you say, “Oh no, this same thing is happening again today.” During the Texas power crisis earlier this year, the mayor of one city literally said to his constituents that they were on their own, that “only the strong will survive.” This is the epitome of the “I” moment we’re living in once again as a nation. As extreme as it sounds to talk about the social Darwinism of the Gilded Age, I think that we are living through an absolute and very clear revival of that cultural mindset today.

COMMUNITY VS. INDIVIDUALISM IN AMERICA, 1890–2017. “Ask not what your country can do for you.” Were those words spoken by JFK in 1961 reveille for a new era — or “Taps” for one that was ending? Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

Ends and means

Not only was there a cultural self-centeredness in the Gilded Age, but there was also a deep sense of isolation and social fragmentation. So Progressives started all of these association-building initiatives to invent new ways of bringing people together. Paul Harris, founder of the Rotary Club, had moved from a small town in the Northeast to Chicago, and described himself as feeling desperately lonely as a result. So he invited a few other professionals to start getting together for lunch to create community. For him, that was an end — to satisfy his own need for connection.

But over time, a lot of reformers begin to realize that there’s real power in associations. They could do more things together than they could do alone. And as they were able to bring people together from disparate worldviews or across class lines, they built bridges and started weaving a stronger social fabric.

That same phenomenon goes on with the Peace Corps: Association is an end, in the sense of wanting to go out and meet people in another culture, have an experience that’s connected. It becomes a means because Volunteers are able to take what they learn, and those relationships, and bring them back to educate people and knit together a more cohesive world. All the research shows the power of social capital as something that’s not only good in and of itself, but also has all these positive externalities that it brings with it: in terms of the health of democracy, the mental and physical health of the people engaging in relationship. That was something that the Progressives discovered that we could look to today and emulate.

We need new ways of bringing people together to solve our problems. We have to center our efforts on that idea of relationship and connection once again.

What causes the shift?

Can we identify the main culprit behind what’s driving these massive — positive or negative — shifts? That’s the million-dollar question — both in the sense of what caused the upswing and what caused the downturn. But that’s hard to do because we’re looking at scores of data sets. It’s a little bit like looking at a flock of birds in flight: They’re all going one direction, then suddenly they change to a different direction. Which one turned first? Which was the leading edge of that change?

It’s a little easier to do with the upturn. It’s harder with the downturn. However, we do know that economics was a lagging indicator; we didn’t fix the economic inequality first. We actually fixed it last, which is very counterintuitive, particularly to people on the Left; there’s a sense that if we could just fix inequality, then we would love each other again. I think there’s a little of that mindset even in the Peace Corps: If we could just help improve the material lot of people in the developing world, that would bring all these other good things. Of course material well-being is critically important, but what’s fascinating is, the other stuff shifted first — particularly culture, both in the upswing and in the downturn.

Of course material well-being is critically important, but what’s fascinating is, the other stuff shifted first — particularly culture, both in the upswing and in the downturn.

During the upswing, those first two-thirds of the 20th century, we were not very careful in creating a “we” that was welcoming to all different kinds of Americans. It was a “we” that was heavily white, male, upper middle class. And there was a lot of pressure to conform to that ideal. So in the 1950s — a decade before you see this big pivot — you see cultural harbingers, people saying, “I don’t like this conformity that’s coming along with intensifying community.” You see Rebel Without a Cause, The Catcher in the Rye, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit — cultural narratives saying there’s a cost to this hyper “we” mentality. That counter-pressure culminated in a kind of “be yourself, don’t worry about any commitments.” The response to hyper-communitarianism became hyper-individualism.

Another harbinger that we can’t fail to mention is race. This highly racialized “we” being built during the first two-thirds of the 20th century essentially meant that the upswing, as great as it was for creating positive change, had knit into it the seeds of its own demise — in the sense that the Progressives were largely racist. They created great programs to address inequality, poverty, and polarization. But they did so while kicking the racial question down the road. As a result, we’ve never really done the work of racial reconciliation. We sort of skipped over that. The New Deal very clearly sacrificed the needs of people of color in the name of progress.

At the peak of this moment — the 1960s, when the Peace Corps was founded and we passed the civil rights legislation — America was ready. Vast majorities of Americans supported the Civil Rights Acts. But the minute racial equality became about more than just laws and regulations, when it became about desegregating neighborhoods and schools, sharing resources with people whom we didn’t have to share them with before, there was a huge white backlash: a very clear “not in my backyard” phenomenon, which to me indicates that we didn’t do the hard work underneath what we were doing legally and politically. It’s hard to say whether the broader societal turn toward “I” precipitated the white backlash, or whether the white backlash fueled the broader turn toward “I.” They were certainly intertwined. It became possible for politicians to exploit white backlash to create a subtly racialized politics with a hyper-individualistic focus. Politicians began to tell Americans it was okay to just look out for number one.

And this translated into an economic mindset that it’s a zero-sum game between growth and equality: You can have equality or you can have growth, but you can’t have both. But look at the first two-thirds of the 20th century: We had high growth and growing equality. Look at material equality between the races and chart that as a ratio: Black Americans were actually doing better at a faster rate than white Americans during this period of high growth. So that idea that you can’t grow the pie and share the pie at the same time is simply false. The opposite was true during 60-odd years of the upswing.

FROM “I” TO “WE” TO “I” IN AMERICAN BOOKS, 1875–2008. First-person pronouns over the years, as tracked through Ngram. Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

If we needed a crisis to unify us, seems like that’s here.

One of the ways in which the 20th century often gets misinterpreted is the idea that we didn’t come together as a nation until the Great Depression and World War II. The Upswing provides a data-based story that shows quite clearly that America’s move toward solidarity did not begin with the Great Depression. It didn’t begin with the New Deal. Or World War II. It began decades earlier, and continued for decades after those acute crises.

What you actually see in the data is a dip, a pause in progress toward “we” during the Roaring Twenties and the 1930s. Then we pull ourselves back into it. Do we need a Great Depression crisis to motivate us? No, we don’t. The Progressives didn’t need it. The crises that motivated them were personal: moral moments of watching terrible things happen to their fellow Americans and feeling appalled at the realization that they had been a part of the systems that made them happen.

That being said, when you look at the American Recovery Plan passed in the spring — that wouldn’t have been possible without the pandemic. The question is whether it’s durable. Many of the policies put in place are historic in addressing the opportunity gap across lines of class and race. But many of those things are set to expire within years. And so the true test is going to be, does that policy change actually represent the manifestation of an underlying cultural and moral change? Or does that policy change represent just a panic in response to this economic crisis? Because 2008 was its own crisis. Did it prompt a new upswing? Absolutely not. We haven’t learned. And so I think a lot of the learning has to happen in our hearts, has to happen in our own sense of morality, and in our own sense of whether we really believe we’re all in this together, or whether that’s just a nice catchphrase that gets us through the crisis and back to business as usual.

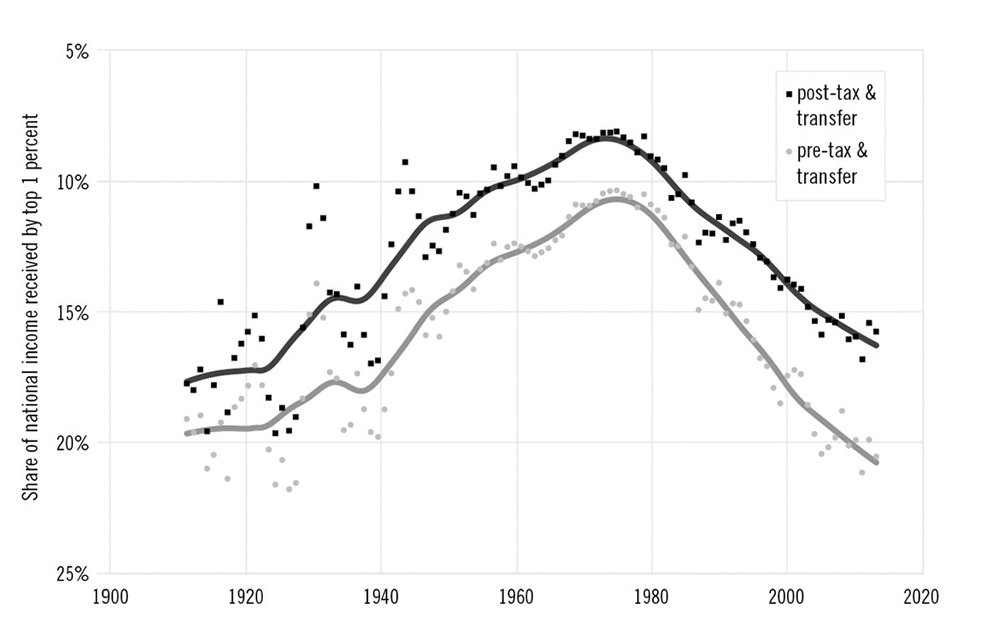

INCOME EQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES, 1913–2014. An important and clearly measurable indicator. But research for The Upswing shows it followed, not led, the other metrics. Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

Digital connections are not enough.

One of the reasons that I was motivated to stay in the Middle East after finishing my Peace Corps service, and to continue to build youth programming, was because we were in Jordan when the Arab Spring unfolded. The Arab Spring is a quintessential example of using Twitter to form a modern social movement — but one that’s extremely fragile. There was no organizing underneath to create something new to replace what was torn down. So in many countries, you have a resurgence of autocracy or militarization. That does hark back to: “What are the lessons from the upswing? How do we do it again today?” The biggest thing is that we can’t skip over the power of face-to-face relationship building and grassroots solution building. What I always used to say when I taught youth in Jordan was that we don’t need more revolutionaries, we need more solutionaries. That was what the American Progressives who drove the upswing believed.

We live in a moment where, particularly because of the influence of technology — specifically social media — we have this idea that new ideas for society can scale extremely fast. But unfortunately that skips over the hard work of building local capacity, connections, and relationships — social capital. Look at the Progressive Era: People didn’t just go out into the street and demand that the robber barons be stripped of their posts at these exploitive companies. They did the work of building support for regulations that would hold exploitation in check: trust-busting and consumer protection agencies. And they also put in place a new infrastructure for an economy that had a different underlying moral logic: publicly owned utilities and unionized workplaces and a progressive income tax.

My co-author and I often get asked: “Are we in the upswing yet? When can we expect the upswing to happen?” The hard answer to that is: It depends on us. If we think we’re going to engineer another upswing just by voicing outrage on social media, we’re wrong. We have to use our agency as citizens to build.

One of my heroines is Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. She was influenced by the work of people like Jane Addams. Day taught that we need to build a new society within the shell of the old. That’s very inspiring as a method. Instead of focusing our energy on tearing down the old, we need to focus on building up the new — ready to step in when the old eats itself alive. It’s certainly possible that our hyper-individualism and eroding social trust will create a collapse of institutions. We’ve seen some of that with the pandemic. What’s going to rise up to replace those defunct institutions? Answering that question with action is where the work of the upswing really happens.

The pandemic has taught us that digital connections are not enough — for either our own human needs or the needs of society. For a long time, we’ve allowed ourselves to believe the fiction that it was okay that we were letting our social fabric fall apart in the face-to-face world, because there was this other online world that was sort of going to magically replace that. But then due to the pandemic we all had to do Zoom Thanksgiving and Christmas, and we realized we need other people in the flesh, not just on a screen. It actually gives me hope that we’re starting to realize it is time to reinvest in face-to-face connection.

There are a lot of really good social innovators out there working to bring people together in physical spaces to work together on projects. That’s the other piece of this in the Peace Corps: One thing you learn quickly as a Volunteer is that the best way to build bridges is co-creating, working together on a project that everyone cares about. Folks who are pursuing initiatives like that in the United States give me a lot of hope.

I am often asked what would be my policy prescription for the administration that would help move us toward an upswing. National service is my absolute go-to answer.

Shaylyn Romney Garrett. Photo courtesy the author

But what keeps me up at night is the fact that there are a lot of countervailing forces working against this positive change. For every good green shoot that we see, there’s a lot of shadow and darkness. I think it happened with the contested election, and on January 6. It keeps happening with debates about masks and vaccines.

Whether things tip or not is really about critical mass. How do you get all the people who are sitting on the sidelines to get in there and work toward pushing us back toward the light? I think that was the story of the Progressive Era. People always ask, “What was the moment that the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era?” There was no clear historical moment. There were all these forces working for good and all these countervailing forces working to tear that down. Ultimately the good won out because people put in enough energy to push it up and over.

I am often asked what would be my policy prescription for the administration that would help move us toward an upswing. National service is my absolute go-to answer. As both a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and a proponent of learning the lessons of history, I am deeply supportive of the idea that creating incentives and opportunities for millions of young people to work together for the good of our nation should be a top priority. This could help us address not only economic inequality, but also polarization, cultural narcissism, and social fragmentation — all the aspects of our current multifaceted crisis. And I think the Peace Corps in particular has a lot to say about how national service could help Americans turn a corner by rediscovering a sense of solidarity — a “we” — as well as find purpose and a sense of American identity that could lead us in a new direction.

This story appears in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022.

READ MORE: “A Life-Altering Detour” — Shaylyn Romney Garrett tells the story of how serving in the Peace Corps led her to work on a national education project in Jordan.