Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleA conversation with Mark Gearan and Keri Lowry see more

From Peace Corps to AmeriCorps to envisioning a quantum leap: 1 million people in the U.S. serving every year — and changing the culture and ethos of service. So how do we get there?

A conversation with Mark Gearan and Keri Lowry.

By Steven Boyd Saum

In 2017, the U.S. government undertook the first-ever comprehensive and holistic review of all forms of service to the nation, and Congress wrote into law the creation of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Over many months, this 11-member bipartisan commission embarked on visits to 42 cities in 22 states, to listen and learn. One area they were charged with examining: military selective service. Then, more broadly: how to expand all kinds of service — domestically and internationally.

The commission issued its final report, including a raft of recommendations, in March 2020 — as a pandemic swept the country. Media attention was minimal — which was both understandable and ironic, given that the crisis underscored the need for service, such as “a Peace Corps for contact tracers.” Even so, recommendations in the report began shaping proposed legislation. And, as this year has shown, there are much bigger changes afoot.

As for selective service: The commission recommended that all citizens, regardless of gender, be registered. That is reflected in next year’s Defense Authorization Act, currently making its way through Congress.

MARK GEARAN served as vice chair for the commission. He was director of the Peace Corps 1995–99 and president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges 1999–2017. Since 2018 he has led the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics.

KERI LOWRY served as director of government affairs and public engagement for the commission. She served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Burkina Faso 2000–02. She has gone on to serve on the National Security Council; as regional director for the Peace Corps for Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa; and as deputy assistant secretary of state. She is currently in the National Security Segment of Guidehouse.

Steven Saum: Let’s start with the big question behind this whole endeavor: If we’re talking about it on a national stage, why does service matter?

Mark Gearan: It goes to the very fabric of our life and civil society. The work can make a real and meaningful difference in communities, in terms of actual outcomes, both domestically and globally. It’s also a powerful statement about our society: about people giving back and caring about others, to share skills and work for the public good. There’s an individual and a collective dimension. And at a time when our nation has these deep divisions, service can be a uniter. It can allow people to work across the whole spectrum of differences that may separate us. Common purpose for the public good is vital for our society’s health and well-being, and for our nation’s security.

Saum: Talk about where we were as a country when this project began — your sense of what was at stake. And how has that changed since the report came out last year?

Gearan: What Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Jack Reed (D-RI) did was really unprecedented: bring together military, national, and public service. It offered a different look, because it affected the very structure of the commission; those appointed by congressional leadership and the president reflected a diversity of experience — military backgrounds, congressional staff, people who had held elected office, some of us directly associated with national service. I liken some of the work we did to de Tocqueville’s tour of our country in his great book: We traveled, did extensive listening sessions.

There is so much good work going on around the country — that’s the good news. But the potential is largely untapped. That led to recommendations that, at the beginning, I would not have imagined. Civic education, for instance, came up through the listening. The report gives a comprehensive road map — and it offers an expansive vision that strengthens all forms of service to meet the needs that we have, and in so doing, strengthens our democracy.

Keri Lowry: The listening sessions helped us understand different facets, the actors in various spaces, how much overlap there was, and ways they could work together to start to bridge divides. The report does a great job of helping put those pieces together. The question is, what is the right ignition to get it going?

Illustration by James Steinberg

Gearan: Service is a fundamental part of who we are as Americans, and how we meet our challenges. But we’re a big country, 330 million people. By igniting the extraordinary potential for service, our recommendations will address critical security and domestic needs, expand economic and educational opportunities, strengthen the civic fabric — and establish a robust culture and ethos of service. Legislatively, part of this effort is in the American Rescue Plan, passed in March 2021; there’s $1 billion for AmeriCorps. That doubles AmeriCorps funding. There is growing support for bipartisan efforts, like the CORPS Act, introduced by Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) and Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS). Hopefully, the broader point will extend to Peace Corps and other streams of service.

Lowry: One great example of where the commitment to service comes together: In 2020, evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers were able to pivot their service when they came back and help domestically, based on what they learned overseas. A lot of them integrated with AmeriCorps efforts. It was very organic.

Gearan: When I served as Peace Corps director, we had 10,000 applications for 3,500 slots every year. I can’t attest that all 6,500 who were not invited would be qualified. But Americans, confronted with those facts, would say something’s fundamentally lacking—that you have thousands raising their hands to serve, and we would not support them. We saw that domestically as well, on our tour, this untapped potential.

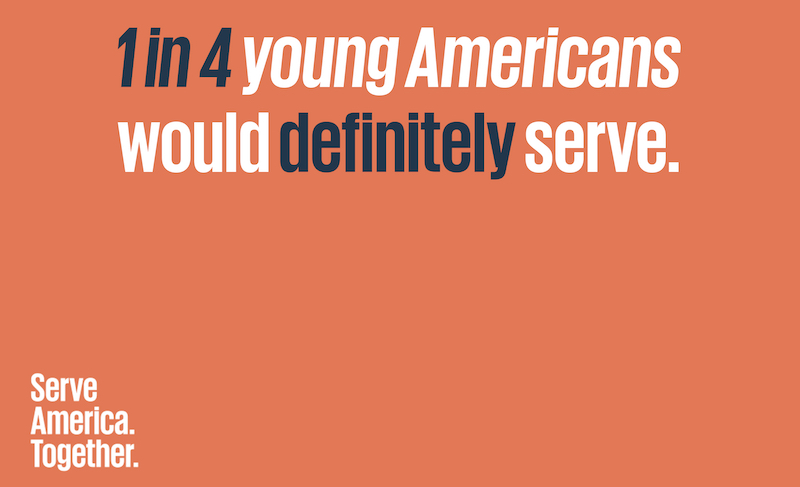

We’ve had 235,000 Americans who’ve served in the Peace Corps and over a million in AmeriCorps. There’s growing interest. We can, by 2031 — the 70th anniversary of President Kennedy’s call — envision a million Americans will begin to serve in military, national, or public service every year. That’s a significant scaling up. When I was director, we had the campaign to get to 10,000 Volunteers by 2000. We got authorizing legislation done. The appropriations weren’t there.

The long-term goal is to cultivate a culture and ethos of service, in which individuals of all backgrounds expect, aspire, and have access to serve. This comes with bipartisan support. The chair of the commission was a former Republican congressman. We had folks appointed by Senator Mitch McConnell, Speaker Paul Ryan; I was appointed by Senator Reed—so the commission did represent a broad ideological spectrum. At the end, we were united in our recommendations.

Lowry: One thing that became clear fairly quickly in the listening sessions is how little people knew about opportunities to serve — or the variety of venues. They might know about one component of service, but not others.

Gearan: One recommendation is the creation of a White House Council to coordinate service efforts across the federal government, to make service more focused and effective — and draw a brighter spotlight on it. Another is to have an online platform providing a one-stop shop for individuals to explore service opportunities. Low awareness and lack of access are real obstacles preventing many Americans from serving. That would also help service organizations — certainly the Peace Corps — find those with the interests or skills they need to achieve their mission. President Kennedy’s vision with the Peace Corps, continuing domestically with AmeriCorps, supported by present bipartisan administrations and Congress over the years, seems a good foundation to build on. Senator Coons’ work with Senator Wicker and other Republicans to advance the CORPS Act is another recent example of bipartisan support. In terms of AmeriCorps, there are real needs being met — and a documented return on investment. A good body of research shows that for every dollar you put in, there’s $17 returned.

With the tragedies of the pandemic, inequities have been laid bare — unequal access to healthcare, education. That has a motivating impact for many lawmakers: How could service meet some of these needs? The past year has put a sense of urgency on answering that.

Saum: The report was released in March 2020 as the country was going into real crisis with the pandemic — a tough time, yet the need for service was even more relevant.

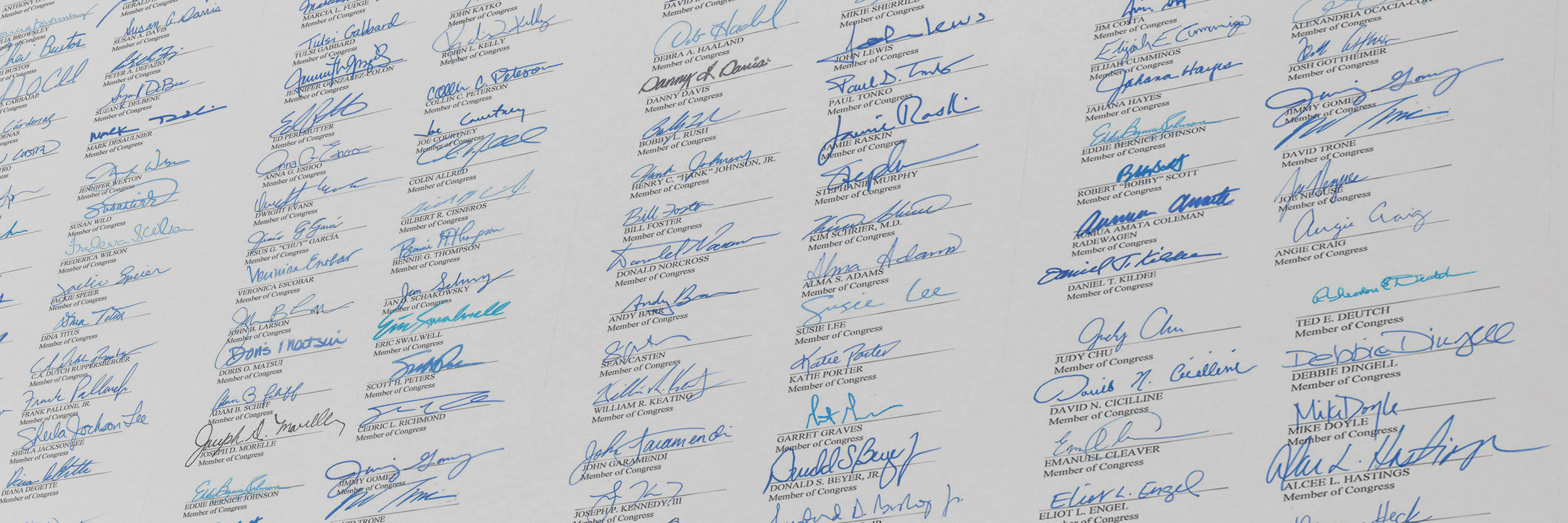

Gearan: Our target date, March 25, was planned months in advance because of necessary deadlines — including printing. It fell at the height of the pandemic and lockdowns. Having said that, we also included, in addition to some 64 recommendations, legislative language — which was helpful to the Hill for operationalizing quickly. Some recommendations helped shape legislation introduced last year, and more this year — such as with Congressman Jimmy Panetta (D-CA), and his caucus’s efforts; and the efforts that Senator Coons and others have picked up in the Senate.

I have seen more momentum and energy associated with thinking about service in an expansive way than I have for many years. It’s almost always been somewhat of a defensive posture: Save AmeriCorps, advance the Peace Corps budget. Along with the legislative tactical piece, this really brought it to a broader level of conversation. It’s a unique moment.

Significantly, it’s also clear that with the tragedies of the pandemic, inequities have been laid bare — unequal access to healthcare, education. That has a motivating impact for many lawmakers: How could service meet some of these needs? The past year has put a sense of urgency on answering that.

We traveled to 22 states and consulted with hundreds of stakeholders, hearing thousands of public comments. It was three years of work charged by the Congress. The initial focus was the selective service and whether there would be a requirement for all Americans to register; that always has news focus. But there’s been a much more fulsome look at our recommendations.

Saum: One common refrain I hear again and again is: “We need a Peace Corps for this, we need a Peace Corps for that.” There’s a recognition that service, and harnessing the energies of more Americans, might be a way to deepen understanding, address problems, and weave the fabric of the country more strongly.

Gearan: There’s the deep respect that the Peace Corps enjoys — deservedly so, thanks to the work of Volunteers, which has laid out this path in many ways.

AmeriCorps has added to it, certainly. Peace Corps was born in another political time, with a vision and energy that has marked six decades of making a difference; that informs so much of what this broad movement is about. When I would travel and listen to different stakeholders, there was frequently more than just a nod to the Peace Corps; there was a foundational element of understanding the importance of service through people’s understanding of the Peace Corps.

So there are many reasons to be grateful to Peace Corps Volunteers and what they have done. It’s also allowed for this moment — as when President Clinton started AmeriCorps, and people understood the shorthand for it was “the domestic Peace Corps.”

Saum: So where do you see the ignition coming from?

Lowry: Look at the meetings that National Peace Corps Association began convening last year, for Peace Corps Connect to the Future. As came up in discussion there, the private sector has a potentially big role here.

The Employers of National Service, and getting more employers to join — that could be an igniter. Show more benefits to young people — or even not young people: You’re learning skills and capabilities that can help you get a job. My company makes efforts to hire candidates that have military, public, and/or national service on their resumes.

To usher in this new era of service, we need the infrastructure to support a million Americans in national service.

Gearan: To support a million Americans serving by 2031, you have to remove some barriers. We know from our travels that AmeriCorps, YouthBuild, Peace Corps can make a difference, meet challenges. The demand is there. To usher in this new era of service, we need the infrastructure to support a million Americans in national service. Part of it is expanding existing programs. Part of it is creating new models — such as a new fellowship program to allow Americans to choose where they want to serve from a list of certified organizations. We made recommendations for funding demonstration projects to pilot innovative approaches, and to increase private sector and interagency partnerships. You’re not going to get to a million without that.

Look at recent numbers for national service: 7,300 Peace Corps Volunteers, 75,000 AmeriCorps volunteers. We’re a long way from a million. But if we really committed ourselves, it’s achievable. Then it would lead to the next level, as Harris Wofford used to say. It won’t be atypical to ask, “Where have you served?”

Lowry: We want to change that conversation, but also start to change the culture.

Saum: For the Peace Corps community, what’s important for them to keep in mind in terms of national service — and making that quantum leap?

Gearan: First, gratitude. I would hope the Peace Corps community and Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, in particular, would feel proud that their service has ushered in a moment for us to significantly enhance the ethos of service in our country, because their work from the early years through today has prepared a pathway for significant expansion.

Secondly, I hope they would be a part of this movement. Their voice is unique, it is appreciated — and they can speak from experience as we work with legislators to advance this expanded national service movement. I’d hope their attentiveness to legislative work and all the good work of NPCA on advocacy would continue. We’re at a real pivotal moment for expanded opportunities for service.

Lowry: Peace Corps gave me opportunities that I never envisioned. For national service to expand and meet the needs of a broader swath of the American population, we need those voices of returned Volunteers to help make national service meet the needs of individuals today. Just because my Peace Corps service included X-Y-Z, that doesn’t mean that the Peace Corps service of someone tomorrow might not have elements that we haven’t been considering to date, or it just hasn’t gotten over the finish line. Their understanding and their voices can help make national service the best that it can be going forward — for their children and their children’s children.

National Peace Corps Association did a phenomenal job of teeing that conversation up last year. It would be wonderful if there’s a way that we can continue that conversation to make national service even better.

We sit atop 60 years of demonstrated efforts by Americans making a difference. That’s a proud legacy. I would say the best way to honor it is by saying, OK, what is the next chapter?

Gearan: In so many ways, the Peace Corps is kind of the crown jewel of so much great service work. Its roots and foundational ethos, thanks to Sargent Shriver and his contemporaries, so informed the broader movement. And if anyone would be calling for innovation and creativity and expanded slots for the Peace Corps’ next chapter, it would be Sargent Shriver.

We’re in this moment, formed and complicated by a pandemic, with challenges and needs that have been exposed for decades as well. But congressional and state leadership see how service is making a difference. We sit atop 60 years of demonstrated efforts by Americans making a difference. That’s a proud legacy. I would say the best way to honor it is by saying, OK, what is the next chapter?

Saum: What does it mean to serve now?

Gearan: As Peace Corps director, when I was visiting Volunteers or meeting RPCVs, the commonality of experience was striking—whether one had served in the ’60s in Ethiopia, in Poland in the ’90s, or South Africa in the 2000s. The shared experience of making a difference was the through line. And that brilliant Third Goal—the domestic dividend—is one of the underappreciated pieces of the Peace Corps.

We have now 235,000 Americans who have served — many in top-level government, business, education, industry, commerce, law, across the spectrum.

Lowry: Go back to that sense of being innovative and looking forward: Peace Corps’ true roots are in building peace and friendship. This is why we’re serving in communities, not just for a short but for a longer duration of time — to really build and seek to understand.

Read the Report

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView.

-

Joanne Roll I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns... see more I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns during public comments. They were not included. I do not believe I was the only one to question. The problem with emphazing "service" is it objectifies the people receiving the "service". They should be placed first, as they are in the First Goal of the Peace Corps.2 years ago

Joanne Roll I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns... see more I do not support the expanded national service progect. I do not believe there is research about exisiting government service projects to support the claims being made. I commented my concerns during public comments. They were not included. I do not believe I was the only one to question. The problem with emphazing "service" is it objectifies the people receiving the "service". They should be placed first, as they are in the First Goal of the Peace Corps.2 years ago

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleLessons from the past in how to become a less polarized country once again see more

The U.S. is profoundly polarized — politically, culturally, socially, and economically. That was true during the Gilded Age, too. Halfway between then and now, John F. Kennedy exhorted his fellow Americans, “Ask not what your country can do for you — but what you can do for your country.” So what happened? And how do we turn things around?

From a conversation with Shaylyn Romney Garrett

We Can Do It! image courtesy the National Museum of American History

In The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett offer a sweeping overview of U.S. history from the Gilded Age to the present, tracing how the country was transformed from an “I” society to a “we” society — and then back again.

Earlier this year we caught up with Garrett to talk about this project — which would seem to have a special resonance for the Peace Corps community. The period their data pinpoints as the pinnacle of an American sense of “we are all in this together” is the early 1960s — the same moment that gave birth to the Peace Corps.

Garrett served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Jordan 2009–11. She is a founding contributor at Weave: The Social Fabric Project, founded by David Brooks and housed at the Aspen Institute, and she writes about rebuilding community and connection in a hyper-individualistic world. Here are edited excerpts from her conversation with WorldView editor Steven Boyd Saum.

Origins of The Upswing

A lot of people ask, “How did you come to write a book with Robert Putnam?” In the year 2000, his seminal book Bowling Alone was published. I was taking his seminar on Community in America, his foray into teaching the research behind Bowling Alone. He closes that book with a look at the Progressive Era as a potential template for how to revive communities, associations, and the social capital that he documented as having been lost over the previous half century. I was captivated by the Progressive Era, particularly the settlement movement. Some people are familiar with Jane Addams and Hull House in Chicago. But there were hundreds of settlement houses across the United States. The movement itself — sort of imported from the U.K. — sought to build bridges across lines of difference and, in a sense, offer educated, college-age people a Peace Corps–type experience within the United States. Something like AmeriCorps today.

I wrote an undergraduate thesis advised by Robert Putnam. In the subsequent 20 years, he and I have worked together on multiple projects, the last of which is The Upswing. Bob brought me into the project at a point when he had discovered a remarkable statistical finding that serves as the backbone of the book.

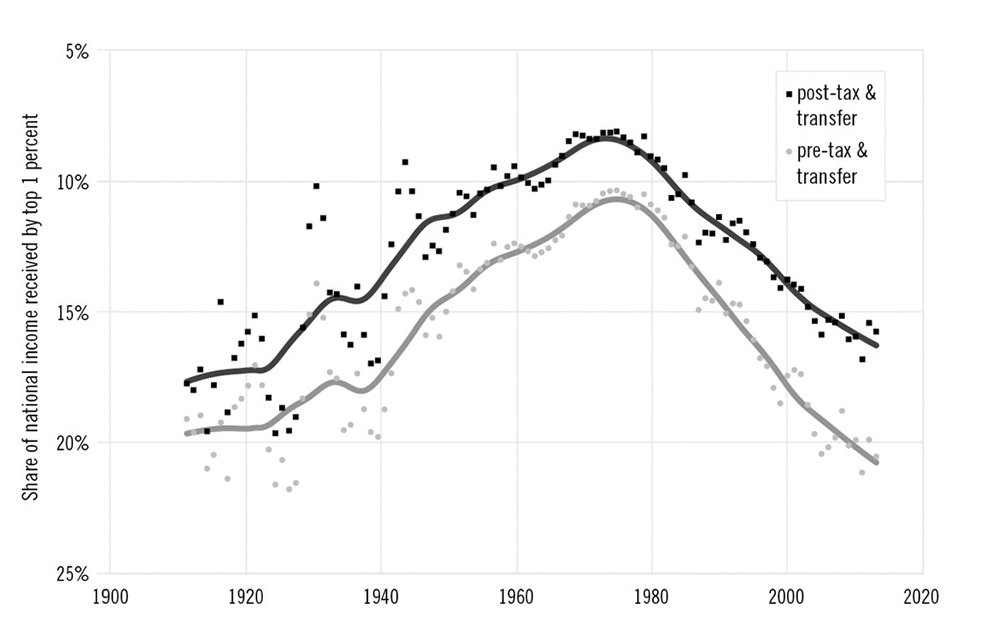

Bowling Alone looked at one aspect of American society — social connectedness, social ties, social cohesion — and asked: What does the trend look like over time? Looking back to roughly the 1960s, Bob saw a marked decline in measures of association, community, and social capital. It was a big finding. But it was a pretty narrow picture. So over the years, Bob started to ask: What was going on with other things — economic inequality, religion?

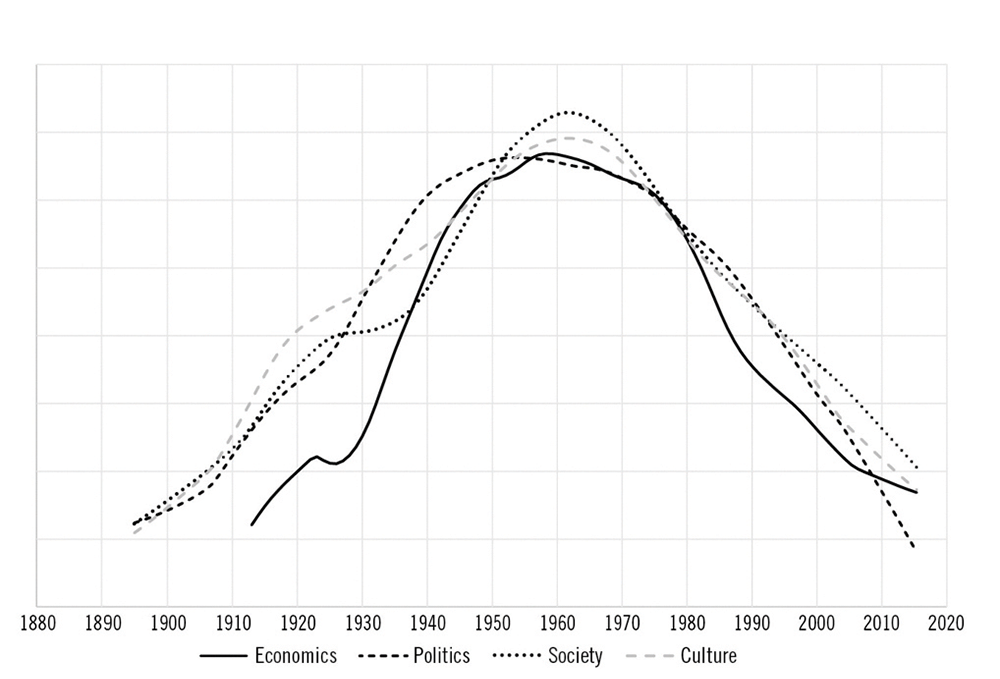

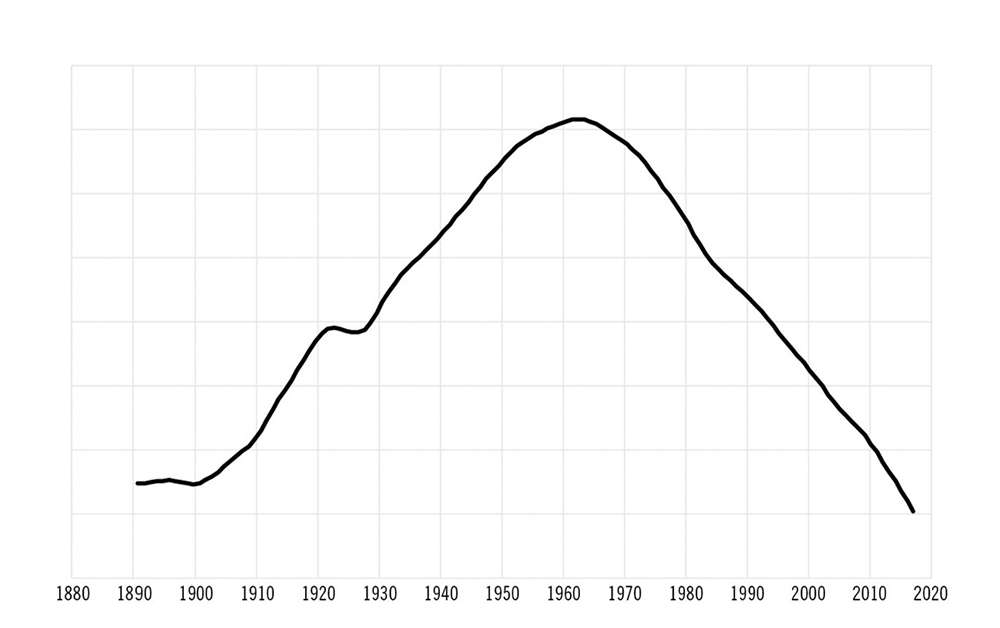

The Upswing incorporates four different metrics. One is social capital, a measure of how connected people are to one another in society. Another is economic inequality. Another is political polarization. The final one is culture — whether we’re more oriented toward a culture of solidarity versus a culture of individualism. It looks at the last century and then some, roughly 1900 to today. When you track those four metrics over this period, they follow the exact same trajectory. For each individual metric, the century-long trends are widely known. But Bob discovered that what scholars had largely thought of as independent phenomena are actually all part of the same century-long meta-trend — a truly striking finding.

In the early 1900s, we were a very unequal, polarized, disconnected, and narcissistic America. Over time, that turned a corner dramatically — into a multifaceted upswing, where all of those measures started moving in a positive direction for six to seven decades. Then, remarkably, in roughly the same five-year period, all of those disparate metrics turned and went the other direction. All that progress we saw over the first two-thirds of the century was reversed, landing us today in a situation remarkably similar to the one in which Americans were living in the late 1800s or early 1900s; historians call it the Gilded Age.

There are different ways you can interpret that upswing/ downturn story. One is to look at the downturn and say, “We’ve had this fall from grace. We need to make America great again. Let’s turn back the clock and go back to this mid-century America that was so wonderful.” A lot of people, particularly of the generation who lived through that period, have been putting forward that narrative. To a certain extent, that narrative culminated in sort of an ugly way with Trump’s MAGA movement.

“If we’ve been in a situation that is, by hard data, measurably identical to the one that we’re living in today — a multifaceted, deep crisis, in all sorts of areas of our society — if we’ve been here before, but we pulled up and out of it, what lessons can we learn from that period that was a downturn that turned into an upswing?”

That’s not really the story Bob or I wanted to tell about these trends. Much more powerful was to ask: “If we’ve been in a situation that is, by hard data, measurably identical to the one that we’re living in today — a multifaceted, deep crisis, in all sorts of areas of our society — if we’ve been here before, but we pulled up and out of it, what lessons can we learn from that period that was a downturn that turned into an upswing?” That becomes a story of when the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era and set us on this upward course that lasted decades. The book looks at the Progressive Era as an instructive period where we can gain inspiration, ideas, and lessons about what to do and what not to do to bring about another upswing.

ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, SOCIAL, AND CULTURAL TRENDS, 1895–2015. Through the early 1960s, all four metrics swing upward: toward equality, bipartisanship, and a greater sense of the common good. The question: How do we move the metrics in that direction again? Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

I-We-I and the origins of the Peace Corps

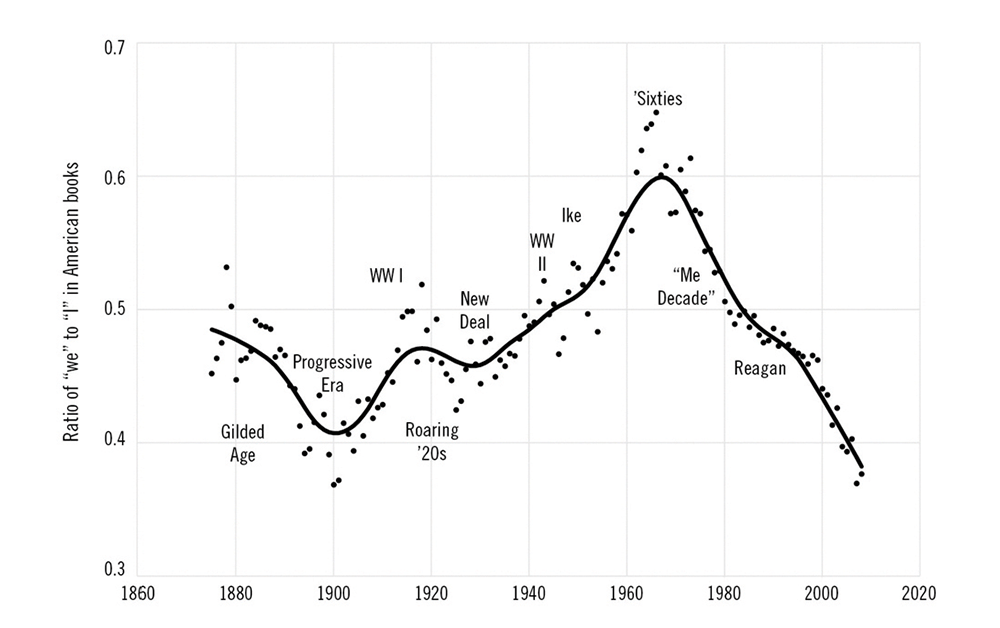

We needed a bit of a shorthand to describe this curve — an inverted U curve: Things were bad, then they went up and got better, then they got bad again. Bob was looking for a way to track cultural trends over time — culture is a notoriously difficult thing to measure statistically — and he discovered Ngram, a database of digitized books in the English language that Google has put together. You can put in different words to track their frequency of use over time. If you put in the word “the” over this 125-year period, it would be a flat line. The incidence of the use of “the” has not changed, which makes sense. However, more culturally tied words are used more or less frequently over time, which gives us a clue about what our culture was more or less focused on during different time periods.

When we track the ratio of the first-person pronoun versus the plural pronoun — “I” and “we” — the curve looks exactly like the curve for economic inequality and polarization. Society was very “I” focused; then “we” as a pronoun became much more common during those first two-thirds of the 20th century. Then it flipped at almost the same time as all of these other curves did, to where “I” became a much more common pronoun. We’re talking about pronouns in all kinds of books, not just academic books: gardening books, cooking books, books about traveling. Mainstream culture books. It’s shocking that it really does look like that, I-we-I.

One interesting point about that moment when the Peace Corps was founded: When we look back to the ’60s we can see two more or less simultaneous phenomena. One was very communalistic, very “we” — the founding of the Peace Corps and the Great Society programs, for example. Then there’s the countercultural movement, which was much more focused on personal rights and freedoms. What’s fascinating about the historical narrative underneath the statistical findings of The Upswing is that you see clearly in the ’60s this moment when the “we” gives way to the “I.”

When John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” we often think it was like reveille for a new era. People at the time really felt it that way … like this was a call for the new and greater heights of “we” that America could move toward, including a more global “we,” which the Peace Corps is part of. However, in retrospect, what felt like reveille for a new era actually ended up being more like “Taps” sounding for an era that was closing.

When John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country,” we often think it was like reveille for a new era. People at the time really felt it that way. Bob Putnam was physically present at that speech and says he felt it zing throughout his entire body — like this was a call for the new and greater heights of “we” that America could move toward, including a more global “we,” which the Peace Corps is part of.

However, in retrospect, what felt like reveille for a new era actually ended up being more like “Taps” sounding for an era that was closing. We went into the ’60s with all of this energy moving toward “we,” but then there were a number of things that turned that energy into a downward trend toward “I” — such that in the 1970s, you get the “Me” Decade, as Tom Wolfe famously called it, on the heels of this president calling not only for a greater sense of “we” in the sense of civil rights, but also that global sense of what kind of influence America could have in a world that was becoming increasingly connected.

In some ways, that was the heyday of something that is now lost. But that heyday was itself the culmination of something that had been building for 60 to 70 years. Often it’s that first piece of the century that we miss. We don’t realize that America wasn’t always that “we”-focused. Quite the contrary. It took quite a while for us to build up to that apogee in American thinking that spawned things like the Peace Corps.

Only the strong survive.

How did an idea like the Peace Corps get into the atmosphere? What were the decades of work and change, and thinking — and change in language — that got us to that point? That story, again, begins back in the Gilded Age — a time, culturally speaking, that was characterized by social Darwinism. Darwin had articulated a theory about the laws that govern the natural world. Much to his chagrin, people in the social sphere began to take those ideas and say, “Survival of the fittest — this is a great way to organize society.” Essentially, society is one giant competition, there are winners and losers, and the devil take the hindmost. It’s the philosophy that spawned the robber barons and horribly exploitative situations that so many Americans — particularly immigrants and women — found themselves in during the Industrial Revolution.

Onto that scene came reformers who began to question the morality of that as an organizing principle. Jane Addams was one moral voice saying, “Something is not right about the exploitative way that we have organized our society. It’s a betrayal of our founding ideals as Americans. It’s also a betrayal of Christian ideals.”

So we began to ask whether we were really being called upon to take care of our most vulnerable, and not just work for the good of the self. That cultural transformation began to take hold. Moral outrage became the reigning narrative; people began to translate outrage into action. It wasn’t just outrage where we wanted to identify all the bad apples and expel them from society. Jane Addams realized that she had become complicit in systems that were exploitative, so she began to work in innovative ways — at the level of the neighborhood, at the level of the tenement — to try and create change. She was working at the level of individual lives, individual families, trying to help them get out of poverty and exploitative employment relationships. Ultimately, her vision became one of changing policies so that it would become illegal for these things to take place, and more social safety nets would be in place.

A lot of the reformers of the Progressive Era created narratives that we describe as “we” narratives. Over time, these really took hold: in policy, politics, economically, culturally, and socially. But there were also ways these didn’t take hold, particularly around issues of race. The “we” that was being built by Progressives was a very racialized “we.” But at the same time, Black Americans were themselves engaged in a very deep effort to build their own “we,” especially as they moved out of the South during the Great Migration — to build a deeply enmeshed society of mutual aid and care that propelled them forward despite the inequality and exclusion that persisted during the 20th century.

Looking back to this period, you might think, “This was this horribly dark moment. How could people have let it get this bad?” But look around; then you say, “Oh no, this same thing is happening again today.” During the Texas power crisis earlier this year, the mayor of one city literally said to his constituents that they were on their own, that “only the strong will survive.” This is the epitome of the “I” moment we’re living in once again as a nation. As extreme as it sounds to talk about the social Darwinism of the Gilded Age, I think that we are living through an absolute and very clear revival of that cultural mindset today.

COMMUNITY VS. INDIVIDUALISM IN AMERICA, 1890–2017. “Ask not what your country can do for you.” Were those words spoken by JFK in 1961 reveille for a new era — or “Taps” for one that was ending? Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

Ends and means

Not only was there a cultural self-centeredness in the Gilded Age, but there was also a deep sense of isolation and social fragmentation. So Progressives started all of these association-building initiatives to invent new ways of bringing people together. Paul Harris, founder of the Rotary Club, had moved from a small town in the Northeast to Chicago, and described himself as feeling desperately lonely as a result. So he invited a few other professionals to start getting together for lunch to create community. For him, that was an end — to satisfy his own need for connection.

But over time, a lot of reformers begin to realize that there’s real power in associations. They could do more things together than they could do alone. And as they were able to bring people together from disparate worldviews or across class lines, they built bridges and started weaving a stronger social fabric.

That same phenomenon goes on with the Peace Corps: Association is an end, in the sense of wanting to go out and meet people in another culture, have an experience that’s connected. It becomes a means because Volunteers are able to take what they learn, and those relationships, and bring them back to educate people and knit together a more cohesive world. All the research shows the power of social capital as something that’s not only good in and of itself, but also has all these positive externalities that it brings with it: in terms of the health of democracy, the mental and physical health of the people engaging in relationship. That was something that the Progressives discovered that we could look to today and emulate.

We need new ways of bringing people together to solve our problems. We have to center our efforts on that idea of relationship and connection once again.

What causes the shift?

Can we identify the main culprit behind what’s driving these massive — positive or negative — shifts? That’s the million-dollar question — both in the sense of what caused the upswing and what caused the downturn. But that’s hard to do because we’re looking at scores of data sets. It’s a little bit like looking at a flock of birds in flight: They’re all going one direction, then suddenly they change to a different direction. Which one turned first? Which was the leading edge of that change?

It’s a little easier to do with the upturn. It’s harder with the downturn. However, we do know that economics was a lagging indicator; we didn’t fix the economic inequality first. We actually fixed it last, which is very counterintuitive, particularly to people on the Left; there’s a sense that if we could just fix inequality, then we would love each other again. I think there’s a little of that mindset even in the Peace Corps: If we could just help improve the material lot of people in the developing world, that would bring all these other good things. Of course material well-being is critically important, but what’s fascinating is, the other stuff shifted first — particularly culture, both in the upswing and in the downturn.

Of course material well-being is critically important, but what’s fascinating is, the other stuff shifted first — particularly culture, both in the upswing and in the downturn.

During the upswing, those first two-thirds of the 20th century, we were not very careful in creating a “we” that was welcoming to all different kinds of Americans. It was a “we” that was heavily white, male, upper middle class. And there was a lot of pressure to conform to that ideal. So in the 1950s — a decade before you see this big pivot — you see cultural harbingers, people saying, “I don’t like this conformity that’s coming along with intensifying community.” You see Rebel Without a Cause, The Catcher in the Rye, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit — cultural narratives saying there’s a cost to this hyper “we” mentality. That counter-pressure culminated in a kind of “be yourself, don’t worry about any commitments.” The response to hyper-communitarianism became hyper-individualism.

Another harbinger that we can’t fail to mention is race. This highly racialized “we” being built during the first two-thirds of the 20th century essentially meant that the upswing, as great as it was for creating positive change, had knit into it the seeds of its own demise — in the sense that the Progressives were largely racist. They created great programs to address inequality, poverty, and polarization. But they did so while kicking the racial question down the road. As a result, we’ve never really done the work of racial reconciliation. We sort of skipped over that. The New Deal very clearly sacrificed the needs of people of color in the name of progress.

At the peak of this moment — the 1960s, when the Peace Corps was founded and we passed the civil rights legislation — America was ready. Vast majorities of Americans supported the Civil Rights Acts. But the minute racial equality became about more than just laws and regulations, when it became about desegregating neighborhoods and schools, sharing resources with people whom we didn’t have to share them with before, there was a huge white backlash: a very clear “not in my backyard” phenomenon, which to me indicates that we didn’t do the hard work underneath what we were doing legally and politically. It’s hard to say whether the broader societal turn toward “I” precipitated the white backlash, or whether the white backlash fueled the broader turn toward “I.” They were certainly intertwined. It became possible for politicians to exploit white backlash to create a subtly racialized politics with a hyper-individualistic focus. Politicians began to tell Americans it was okay to just look out for number one.

And this translated into an economic mindset that it’s a zero-sum game between growth and equality: You can have equality or you can have growth, but you can’t have both. But look at the first two-thirds of the 20th century: We had high growth and growing equality. Look at material equality between the races and chart that as a ratio: Black Americans were actually doing better at a faster rate than white Americans during this period of high growth. So that idea that you can’t grow the pie and share the pie at the same time is simply false. The opposite was true during 60-odd years of the upswing.

FROM “I” TO “WE” TO “I” IN AMERICAN BOOKS, 1875–2008. First-person pronouns over the years, as tracked through Ngram. Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

If we needed a crisis to unify us, seems like that’s here.

One of the ways in which the 20th century often gets misinterpreted is the idea that we didn’t come together as a nation until the Great Depression and World War II. The Upswing provides a data-based story that shows quite clearly that America’s move toward solidarity did not begin with the Great Depression. It didn’t begin with the New Deal. Or World War II. It began decades earlier, and continued for decades after those acute crises.

What you actually see in the data is a dip, a pause in progress toward “we” during the Roaring Twenties and the 1930s. Then we pull ourselves back into it. Do we need a Great Depression crisis to motivate us? No, we don’t. The Progressives didn’t need it. The crises that motivated them were personal: moral moments of watching terrible things happen to their fellow Americans and feeling appalled at the realization that they had been a part of the systems that made them happen.

That being said, when you look at the American Recovery Plan passed in the spring — that wouldn’t have been possible without the pandemic. The question is whether it’s durable. Many of the policies put in place are historic in addressing the opportunity gap across lines of class and race. But many of those things are set to expire within years. And so the true test is going to be, does that policy change actually represent the manifestation of an underlying cultural and moral change? Or does that policy change represent just a panic in response to this economic crisis? Because 2008 was its own crisis. Did it prompt a new upswing? Absolutely not. We haven’t learned. And so I think a lot of the learning has to happen in our hearts, has to happen in our own sense of morality, and in our own sense of whether we really believe we’re all in this together, or whether that’s just a nice catchphrase that gets us through the crisis and back to business as usual.

INCOME EQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES, 1913–2014. An important and clearly measurable indicator. But research for The Upswing shows it followed, not led, the other metrics. Courtesy Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett

Digital connections are not enough.

One of the reasons that I was motivated to stay in the Middle East after finishing my Peace Corps service, and to continue to build youth programming, was because we were in Jordan when the Arab Spring unfolded. The Arab Spring is a quintessential example of using Twitter to form a modern social movement — but one that’s extremely fragile. There was no organizing underneath to create something new to replace what was torn down. So in many countries, you have a resurgence of autocracy or militarization. That does hark back to: “What are the lessons from the upswing? How do we do it again today?” The biggest thing is that we can’t skip over the power of face-to-face relationship building and grassroots solution building. What I always used to say when I taught youth in Jordan was that we don’t need more revolutionaries, we need more solutionaries. That was what the American Progressives who drove the upswing believed.

We live in a moment where, particularly because of the influence of technology — specifically social media — we have this idea that new ideas for society can scale extremely fast. But unfortunately that skips over the hard work of building local capacity, connections, and relationships — social capital. Look at the Progressive Era: People didn’t just go out into the street and demand that the robber barons be stripped of their posts at these exploitive companies. They did the work of building support for regulations that would hold exploitation in check: trust-busting and consumer protection agencies. And they also put in place a new infrastructure for an economy that had a different underlying moral logic: publicly owned utilities and unionized workplaces and a progressive income tax.

My co-author and I often get asked: “Are we in the upswing yet? When can we expect the upswing to happen?” The hard answer to that is: It depends on us. If we think we’re going to engineer another upswing just by voicing outrage on social media, we’re wrong. We have to use our agency as citizens to build.

One of my heroines is Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. She was influenced by the work of people like Jane Addams. Day taught that we need to build a new society within the shell of the old. That’s very inspiring as a method. Instead of focusing our energy on tearing down the old, we need to focus on building up the new — ready to step in when the old eats itself alive. It’s certainly possible that our hyper-individualism and eroding social trust will create a collapse of institutions. We’ve seen some of that with the pandemic. What’s going to rise up to replace those defunct institutions? Answering that question with action is where the work of the upswing really happens.

The pandemic has taught us that digital connections are not enough — for either our own human needs or the needs of society. For a long time, we’ve allowed ourselves to believe the fiction that it was okay that we were letting our social fabric fall apart in the face-to-face world, because there was this other online world that was sort of going to magically replace that. But then due to the pandemic we all had to do Zoom Thanksgiving and Christmas, and we realized we need other people in the flesh, not just on a screen. It actually gives me hope that we’re starting to realize it is time to reinvest in face-to-face connection.

There are a lot of really good social innovators out there working to bring people together in physical spaces to work together on projects. That’s the other piece of this in the Peace Corps: One thing you learn quickly as a Volunteer is that the best way to build bridges is co-creating, working together on a project that everyone cares about. Folks who are pursuing initiatives like that in the United States give me a lot of hope.

I am often asked what would be my policy prescription for the administration that would help move us toward an upswing. National service is my absolute go-to answer.

Shaylyn Romney Garrett. Photo courtesy the author

But what keeps me up at night is the fact that there are a lot of countervailing forces working against this positive change. For every good green shoot that we see, there’s a lot of shadow and darkness. I think it happened with the contested election, and on January 6. It keeps happening with debates about masks and vaccines.

Whether things tip or not is really about critical mass. How do you get all the people who are sitting on the sidelines to get in there and work toward pushing us back toward the light? I think that was the story of the Progressive Era. People always ask, “What was the moment that the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era?” There was no clear historical moment. There were all these forces working for good and all these countervailing forces working to tear that down. Ultimately the good won out because people put in enough energy to push it up and over.

I am often asked what would be my policy prescription for the administration that would help move us toward an upswing. National service is my absolute go-to answer. As both a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and a proponent of learning the lessons of history, I am deeply supportive of the idea that creating incentives and opportunities for millions of young people to work together for the good of our nation should be a top priority. This could help us address not only economic inequality, but also polarization, cultural narcissism, and social fragmentation — all the aspects of our current multifaceted crisis. And I think the Peace Corps in particular has a lot to say about how national service could help Americans turn a corner by rediscovering a sense of solidarity — a “we” — as well as find purpose and a sense of American identity that could lead us in a new direction.

This story appears in the 60th-anniversary edition of WorldView magazine.

Story updated January 17, 2022.

READ MORE: “A Life-Altering Detour” — Shaylyn Romney Garrett tells the story of how serving in the Peace Corps led her to work on a national education project in Jordan.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleIn a time of global crisis, Lex Rieffel explores new ways forward for Peace Corps. see more

COVID-19 upended systems. Now we’re focused on structural racism like never before. So how can Peace Corps help this nation live up to its ideals?

By Lex Rieffel

Illustration by Sandra Dionsi / Theispot

The COVID-19 pandemic that erupted at the beginning of this year massively disrupted behavior that has for a long time been taken for granted — between people and between nations. Then in May the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis under the knee of a policeman sparked unprecedented demonstrations around the world to end systemic racial discrimination and improve social justice.

Years will pass before new patterns of home life and work life become normal and before international relations achieve new forms of openness and interaction. Policies, programs, projects, and institutions will have to be adapted to meet this new reality. It will not be easy. It will require political will not seen since World War II, and a reckoning with racism that precedes the founding of the United States.

As it prepares to celebrate in 2021 its 60th year of working to make the world a better place, the Peace Corps, too, will have to change. Even the three goals announced at its founding will need to be reconsidered:

1. To help the people of interested countries in meeting their need for trained men and women.

2. To help promote a better understanding of Americans on the part of the peoples served.

3. To help promote a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans.

Perhaps the focus should be less on training and more on meeting global challenges like climate change and conflict.MY PEACE CORPS GROUP, India XVI, served in the mid-1960s. This was the heyday of the Peace Corps. It had blossomed to become a vibrant agency in less than ten years, with almost 16,000 Volunteers serving in scores of countries. Then the Vietnam War and President Nixon crippled both the supply of volunteers and the demand from host countries, reducing the number of serving Volunteers to under 5,000 in the early 1980s.

A passionate campaign in that decade produced enough bipartisan support in the Congress to stop the decline in the number of Volunteers and begin a slow buildup. However, three successive presidents — Clinton, Bush-43, and Obama — failed to achieve their election campaign pledges to double the number of serving Volunteers from the levels they had inherited; Clinton inherited some 5,400, Obama just over 7,000 — about the number now. There was insufficient support in the Congress for a bigger Peace Corps budget to overcome the opposition of a vocal minority. Voters seemed convinced that U.S. national security depended more on putting boots on the ground overseas than sneakers on the ground.

Anti-Peace Corps sentiment in the Congress has strengthened during the Trump Presidency. A bill was introduced in the House last year to defund the Peace Corps and attracted more than 100 votes. It’s easy to imagine the Peace Corps being defunded in a second Trump Administration. But it’s also possible to imagine a stronger Peace Corps emerging under a new president.

Revolutionary and Inclusive

Wearing my economist hat, here is my best guess about the supply and demand for Peace Corps Volunteers, regardless of who is elected in November.

It seems likely that more American men and women will be interested in joining the Peace Corps in the coming years because higher education and the job market in the USA have been so greatly disrupted. Even before the pandemic arrived, the job market was being reshaped by artificial intelligence, robotics, and other factors. The “normal” pattern of getting a full-time job with benefits was no longer the default option for many graduates. The gig economy was expanding visibly.

The pandemic has delivered a body blow to higher education that will almost certainly lead to dramatic changes. Already we see far more high school graduates exploring gap year options. More fundamentally, financial constraints are likely to reduce residential enrollment substantially for several years. College dropouts and people who have lost their jobs due to the pandemic, regardless of their age, may find the Peace Corps and other forms of public service to be appealing options.

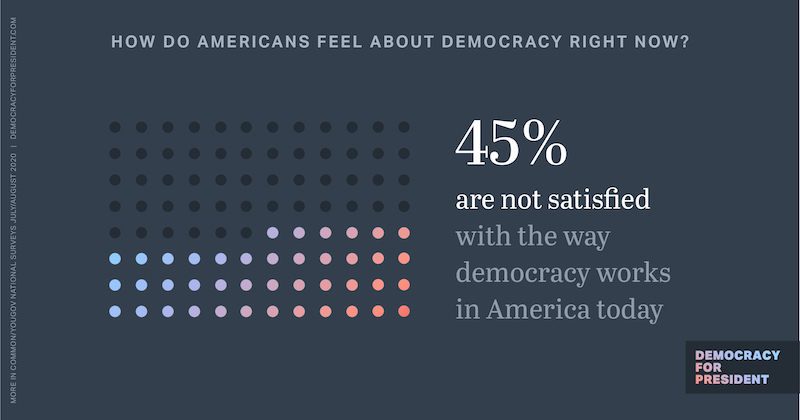

The biggest unknown on the supply side is how the current debate on national service will play out. Too few Americans are aware of the existence of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Mandated by the Congress in the authorizing legislation for FY2017, the Commission issued its final report in March 2020, and held its public rollout on June 25. Its recommendations represent “a revolutionary and inclusive approach to service for Americans.”

The National Commission found compelling reasons “to cultivate a widespread culture of service” in the United States. Its report states that bold action is required, not incremental change. Its recommendations begin with “comprehensive civic education and service learning starting in kindergarten” and extend to making service-year opportunities so ubiquitous that “service becomes a rite of passage for millions of young adults.” If acted upon, the result will enhance national security and strengthen our democratic system.

The Commission proposes an ambitious goal of having 5 million Americans every year begin participating in military, national, or public service by 2031.

The Commission proposes an ambitious goal of having 5 million Americans every year begin participating in military, national, or public service by 2031. Among these, it calls for one million to be supported by federal funding, ten times the number currently supported. The Peace Corps is explicitly included in this vision, though the Commission does not recommend a specific number of Peace Corps Volunteers. It does explicitly call for an expansion of Peace Corps Response, making the program more accessible to older Americans and people with disabilities, with increased opportunities for “virtual” volunteering.The pandemic could actually accelerate the idea of creating a voluntary national service norm, for women as well as men. Bipartisan legislation has already been introduced to scale up AmeriCorps and other domestic service programs. Experts and activists have called for establishing new programs for rapid employment of contact tracers and health workers to stop the pandemic in the USA. The ongoing demonstrations against racism in the wake of George Floyd’s murder have brought forth proposals for new community-based service initiatives. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) created in the Great Depression of the 1930s has been cited as a model for a form of service program that could emerge to reduce the highest unemployment rate the country has seen in the past 75 years: 14.7 percent at the end of April and 13.3 percent at the end of May.

The Peace Corps budget is a tiny part of the federal budget. For example, its appropriation of $410.5 million for FY2020 was less than two-tenths of one percent of the Defense Department’s budget request for weapons procurement. It shouldn’t take much political will in the Congress to double or triple the Peace Corps’ budget if there is growing voter support for national service. The crucial question will then become how many of the men and women seeking a service opportunity will be attracted to living in a foreign country. A big part of the answer will depend on evolving perceptions of the health and security risks of working outside the USA. Quite possibly, fewer Americans will want to spend two years in some remote village in a country they couldn’t find on a map, even with a promise of reliable internet access. On the other hand, some of the recently repatriated Peace Corps volunteers are continuing their service online, and forms of virtual service internationally may become more feasible and attractive.

In short, the supply could conceivably be sufficient to produce a Peace Corps with as many as 100,000 volunteers serving abroad by 2031, but that must be considered a best-case outcome.

The demand from host countries, by contrast, may be insufficient to even maintain the pre-pandemic level of 7,000 volunteers in the field. There will be an early test of this demand: how many of the 60-odd countries hosting volunteers before the pandemic erupted will welcome them back. The process of renegotiating programs with these countries will undoubtedly be challenging.

Who needs the Peace Corps?In the 1960s, the whole world — even countries in the Communist Bloc — looked up to the USA with envy because of its high standard of living, its rich culture (movies, theaters, museums, etc.), its outstanding universities, its technological advances (putting men on the moon), its fight for civil rights, its enduring democratic political system, its international leadership. Few countries still look up to the USA in this comprehensive way. Over the past two decades or more, we have squandered our position of preeminence.

It seems extremely unlikely that the world will revert to the openness that existed a decade ago. There will be less trade, less tourism, less migration.

That’s just the beginning of the problem. The process of globalization led by the United States started slowing down with the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., in 2001 and halted with the Global Financial Crisis emanating from the USA in 2007–08. By 2015, globalization was unwinding. That was the year the refugee exodus from the Middle East quickly led most European countries to restrict immigration severely. Another big setback came with the Brexit vote in June 2016, followed a few months later by the election of President Trump on an anti-globalization platform. It seems extremely unlikely that the world will revert to the openness that existed a decade ago. There will be less trade, less tourism, less migration. Climate change is likely to produce more border closing than border opening.In short, in a world where most governments are preoccupied with addressing internal problems and in which internet access is penetrating into the far corners of the globe, few countries are likely to need Peace Corps volunteers or want them.

At the same time, the rise of China and other countries forces us to reconsider our national security in a world where the U.S. population of 330 million represents barely 4 percent of Earth’s total population of 7.7 billion. Military power cannot possibly be enough to maintain the respect of the rest of the world. To some extent, this power seems to have made the rest fear the USA more than admire it. In this case, America’s national security may depend greatly on how well the rest of the world understands the positive features of our country. Promoting that understanding just happens to be the second goal of the Peace Corps.

FROM A DEEPER DIVE into the risk of border-related conflict in the coming decades emerges an argument that a “whole world peace corps” is needed more than lots of separate national Peace Corps-like programs. Thus, the most ambitious approach to reinventing the Peace Corps might be to transform the existing UN Volunteer program into a World Peace Corps, with every country establishing an affiliate. The U.S. Peace Corps, for example, would be rebranded as “World Peace Corps - USA.”

By contrast, the least ambitious vision for the post-pandemic Peace Corps would be to re-establish its recent level of 7,000 serving volunteers, making the adjustments necessary to restore programs with previous host countries and find some new ones. This should be doable — though it’s important not to underestimate the complexities that will arise.

So, what is the most impactful and politically feasible approach that the large “Peace Corps family” should pursue? A time of crisis like today’s provides an ideal opportunity to assess and debate alternatives. For this reason, the National Peace Corps Association is convening a summit on July 18 to explore the future of Peace Corps — and the broader Peace Corps community.

Among options worth considering: programs that bring to the USA as many volunteers from countries hosting Peace Corps volunteers as we send to them.

There are a number of options worth considering between a World Peace Corps and reverting to the barely visible program of the past 40 years. Most important among them may be two-way service programs: programs that bring to the USA as many volunteers from countries hosting Peace Corps volunteers as we send to them. This was part of Sargent Shriver’s vision back in the 1960s, but it was a nonstarter with the U.S. Congress. Now we have to ask ourselves why any country negotiating with the Peace Corps would fail to insist on a two-way program.The resistance, sadly, will be within the USA, despite the fact that there is an abundance of service work that men and women from foreign countries could usefully do here. Disaster relief is just one obvious area. Few Americans know that thousands of individuals in Ireland raised more than $3 million for the Navajo nation to help fight the pandemic. Firefighters have come from as far away as Australia to battle wildfires in California and other states.

Teaching is probably the most interesting area for two-way service. Think of the benefits of having at least one foreign teacher in every middle school and high school in the USA. They could teach foreign languages, geography, music, sports, and more. Their counterparts, Americans serving as volunteer teachers abroad, would do the same.

This could be the easiest way to build on the Third Goal of the Peace Corps in the post-pandemic world: helping Americans to better understand people in the rest of the world. It would also represent a strong step to counter allegations that the Peace Corps is a manifestation of “white saviorism.”

Such a two-way teaching program could be established within the State Department (like the Fulbright and the Humphrey programs) or under the Corporation for National and Community Service. But there is one glaring problem here.

Anti-Peace Corps sentiment in the Congress won’t go away in a post-Trump administration. A bigger, better, bolder Peace Corps in its current form as a federal agency may well be a political nonstarter even under a Democratic administration. If so, converting the Peace Corps from a U.S. government agency to an independent, private sector NGO might represent the best chance to build an international service program that continues to be “the best face of America overseas.”

With a nonpartisan board of trustees composed of eminent personalities, this NGO could be generously funded by individual donors, foundations, and corporations, as well as receiving core grants from the federal budget. Largely freed from government fetters, it could iterate toward an array of programs of international service that contribute materially to a more peaceful and prosperous world. Operating within this organization, the Peace Corps could remain the gold standard of international service.

Yet now we have a fresh challenge — which is also coming to terms with a very old problem. To remain the gold standard, the Peace Corps will have to become more diverse, more inclusive. The report of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service has noted that our existing federal service programs have primarily benefited people from better educated and higher income families. This is true about the Peace Corps as much as other programs.

I hope readers will not simply “stay tuned” for a report from the National Peace Corps Association following the July 18 summit. I hope they will weigh in with constructive comments. For sure, there will be no consensus on how the Peace Corps should evolve, but I believe that the members of the Peace Corps family — more than 200,000 strong — are in the best position to understand the challenges and find a sensible way forward.

Lex Rieffel (India 1965–67) is a nonresident fellow with the Stimson Center. He served two years of active duty in the U.S. Navy before joining the Peace Corps. He has been an economist with the Treasury Department and USAID, a senior advisor for the Institute of International Finance, and a scholar at the Brookings Institution.

- Dan Baker and Steven Saum like this.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleA letter from the President of the National Peace Corps Association see more

By Glenn Blumhorst

DO YOU REMEMBER WHERE YOU WERE when you heard the news? That the U.S. Peace Corps had made the difficult and unprecedented decision to suspend programs indefinitely, evacuating 7,300 volunteers serving in more than 60 countries due to coronavirus, and informing them that their service had ended. That more than 100,000 Americans had died from COVID-19.

That more than 40 million had applied for unemployment. That George Floyd had died after a policeman in Minneapolis pressed a knee on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. But George Floyd’s name is only one of a terrible litany of Black men, women, and children who have died at the hands of police.

Our nation is reeling. How could it not be?

HERE AT HOME, the toll of coronavirus has hit Black and Brown communities particularly hard. So have job losses. In a time of global pandemic, we’re faced once more with a brutal truth articulated years ago by Sargent Shriver, who founded the Peace Corps: “We must also treat the disease of racism itself.”

How do we do that? Fundamentally, those of us in the Peace Corps community embark on service as Volunteers to promote world peace and understanding. This is our world, right here. One where empathy and justice must guide us — as we head out into the world, as we bring it back home. Our commitment to that doesn’t stop at the border. As National Peace Corps Association Board Director Corey Griffin has often put it, “By living out Peace Corps values here at home, we’ll have a better society, one that honors and celebrates our differences.”

Systemic racism is an issue much bigger than our community. But we need to do what we can. Because both within the Peace Corps community and outside of it, Black Lives Matter. We have a moral obligation to use our stature as a community — and the credible voice, when it comes to speaking for peace and understanding — to lead by example in proactively fighting against unjust and unequal treatment of people of color.

Evidence of racial inequity exists in many forms. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed deep systemic problems in our country. Continued violence and police brutality against the Black community has ignited protests coast to coast — and internationally. And while the ongoing struggle for racial equity and social justice resonates strongly with core Peace Corps values, Volunteers of color continue to share challenges of racism, bias, and exclusivity, describing experiences during recruitment, in service, and after returning home. That is true of Volunteers who served decades ago — and those who just evacuated.

As part of a vibrant and engaged community, we’ve listened to and been inspired by voices calling on Peace Corps to do and be better. We know that we at NPCA need to hold ourselves accountable as well. We’ve heard questions from RPCVs wanting to know historical data: How many Black Volunteers have served? More than that, we’ve heard from Black Volunteers asking: Will you stand with us? Will you support us? Will you lead to help make the changes we need to make?

We’ve heard from Black Volunteers asking: Will you stand with us? Will you support us? Will you lead to help make the changes we need to make?

We must. We are. And we will. For those of you who receive our email newsletter, you’ve already seen the statements and action plans NPCA leadership has put in place. We’ve launched a digital hub for news, events, stories, and resources focused on racial justice in the Peace Corps community. In June we co-sponsored a panel on “A Moment to Lean In: Courageous Conversations on Racial Equity in International Service.” But this is only the beginning of the work we have before us.

We’ve already heard from some Volunteers who served across the decades that they are heartened to see that we are grappling with the fact that the agency and our community need to take a stand against systemic racism. It’s long overdue. They note that the sense of cause and purpose that comes with this effort is what inspired them to join the Peace Corps in the first place. Motivated by equity and justice, this kind of commitment can and does change lives and communities, institutions and systems.

Transformation

BACK IN MARCH, when Peace Corps brought Volunteers home, the agency’s top priority was ensuring Volunteers’ safety and security. But many returning volunteers felt like they had been fired and left with no benefits and little support as they arrived home.

To its credit, over the past several months the agency focused squarely on the complex process of seeking to ensure that the evacuated Volunteers had some safety net. Meanwhile, the broader Peace Corps community, which includes some 250,000 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers over the past 59 years, rallied to welcome and support the evacuated Volunteers. NPCA ramped up a number of programs to help.

Having left my rural Missouri home to serve as a Peace Corps volunteer in Guatemala from 1988 to 1991, I felt a visceral connection with the 169 volunteers preparing to leave Guatemala. I spoke with them on video chat. They shared personal stories and photos on social media, trying to come to grips with what it means to be evacuated from the schools and host families and wider communities they were part of. As they said their goodbyes, I imagined many of them pledged to return. One day they will — as Volunteers once more, or as their life journeys wind back there in years to come.

But some big questions loom. One role that Volunteers play time and again, in building their relationships with communities, is helping those communities better understand the diversity and complexity of the United States and its people. How well will this country be living up to its ideals when Volunteers do return?

I often say that we seek to make Peace Corps be the best that it can be. That includes bearing witness to inequity in our work around the world — and bringing that understanding back home.

THIS MOMENT on the eve of the 60th anniversary of Peace Corps, must be transformed: from a sad chapter in our history to an unparalleled opportunity to shape a Peace Corps around the world’s changing needs. And, crucially, to shape a Peace Corps community that truly reflects our nation as it should be.

With that in mind, this summer we have hosted a series of events: Peace Corps Connect to the Future. We convened a series of eight town hall meetings on topics ranging from diversity, equity, and inclusion to Peace Corps policies for a changed world. Then, to bring together ideas from all the town halls, we hosted a half-day summit on July 18. Here’s a video of the entire summit. Building on that, we’ll be shaping policy recommendations and an action plan for the Peace Corps community. Those will carry us into the months and years ahead.

Peace Corps’ underlying mission — to promote world peace and friendship — is as vital today as it was when the program began nearly 60 years ago. But as the past few months have made painfully clear, the importance of that work here at home is more critical than ever. I often say that we seek to make Peace Corps be the best that it can be. That includes bearing witness to inequity in our work around the world — and bringing that understanding back home.

Curtis Valentine, an education policy expert, served as a Volunteer in South Africa from 2001 to 2003 — the only African American man in his cohort. His own intimidating encounters with U.S. police as a young man are documented alongside those of 99 other Black men in the book The Presumption of Guilt. A few weeks ago he was talking with WorldView editor Steven Saum. “Everyone who has served has a story about an injustice,” Valentine said, “whether it be racial, whether it be gender, whether it be socioeconomic, religious … something as Volunteers we saw and said: ‘This is unacceptable.’ I think we are uniquely qualified and prepared to respond in our own country because of our experience around the world. And in many ways, we have an obligation to do so. This is our time.”

Glenn Blumhorst is President & CEO of National Peace Corps Association. He welcomes your comments: president@peacecorpsconnect.org.

The original version of this essay appeared in the Summer 2020 print edition of WorldView, published in July.

-

Ana Victoria Cruz posted an articleNational Service includes programs such as Peace Corps, AmeriCorps, Senior Corps, and YouthBuild. see more

By Mark Gearan

The bipartisan, 11-member National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service was created by Congress to find ways to increase participation in military, national, and public service and to review the military selective service process. Our goal is to ignite a national conversation about the importance of service as we develop recommendations for the Congress and the President by March 2020.

I am honored to serve as vice chair for national and public service and was privileged to deliver opening remarks during two national service hearings held by the Commission in March 2019. From my years as Peace Corps director, I know RPCVs will have a strong interest in our work and I appreciate this opportunity to update the community on our efforts.

From February to June of this year, the commission held 14 public hearings and released eight staff memoranda on various topics related to our mission. In March, the commission held two hearings on national service and released a staff memorandum summarizing research and outlining potential policy options the commission is considering on increasing Americans’ propensity to participate in national service.

National service is defined in the commission’s mandate as “civilian participation in any non-governmental capacity, including with private for-profit organizations and non-profit organizations (including with appropriate faith-based organizations), that pursues and enhances the common good and meets the needs of communities, the states, or the nation in sectors related to security, health, care for the elderly, and other areas considered appropriate by the Commission.”

National Service includes programs such as Peace Corps, AmeriCorps, Senior Corps, and YouthBuild. The Commission is also considering ways to include faith-based, non-profit, and private-sector organizations in creating and promoting national service opportunities.

As the vice chair for national and public service, former Peace Corps director, and a former college president, our hearings on national service were close to my heart, especially as we hosted them at the Bush School of Government and Public Service. President George H.W. Bush lived his life in service to others and as a leader who believed service could unite Americans. He served as a champion of national service, and it was an honor for the commission to host both hearings at the school that honors his legacy. And I note with pride, that Texas is fourth in the list of top Peace Corps volunteer-producing states with 350 individuals serving in the Peace Corps in 2018.

Reducing Barriers to Service

A study commissioned by Service Year Alliance in 2015 demonstrated that fewer than one third of 14 to 24-year-olds are aware of service year options. The Commission wants to assure access to these opportunities for all Americans. To do this, the Commission is interested in minimizing barriers to serve, such as stipends and benefits. Improving access to national service will ensure that the diversity of national service volunteers reflects that of the nation.

When the Peace Corps was established in 1961, it was an innovative and bold idea. Today, more than 230,000 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers demonstrate the enduring strength of that idea. Peace Corps Volunteers have represented the United States in 141 countries and have left behind a legacy of peace and friendship.

At our hearing, Michelle Brooks, Peace Corps chief of staff, testified and argued that federal government investment in programs such as Peace Corps and the various programs of the Corporation for National and Community Service ultimately results in the development of passionate and informed global citizens. Each Peace Corps Volunteer returns to the United States with a proven track record of working in a cross-cultural setting and appreciating and respecting the richness of working across differences.

Brooks also shared recommendations the agency would like the commission to consider. Two of those suggestions were: extending Noncompetitive Eligibility status to three years for RPCVs, bringing it in line with most other authorities granting that status; and an NCE Service Registry, an idea Peace Corps is piloting with two federal agencies.

Ms. Brooks’ full testimony can be found on the Commission’s website at www.inspire2serve.gov. Do you have additional recommendations to those provided by the Peace Corps during our March hearings on national service?

Join the Discussion

I invite you to join us in this important conversation. Our hope is to spark a movement: every American — especially young Americans — inspired and eager to serve. Talk to your friends, family members, neighbors, colleagues and fellow returned Volunteers about the commission, your service experience, and how we can create more national service opportunities for Americans. We want to hear from all of you!

Share your ideas with the commission through our website on any aspect of the commission’s mission. For example, how can we create more national service opportunities for Americans, and how can we improve the current national service policies and processes?

Stay up to date on the commission’s activities and download the Interim Report at www.inspire2serve.gov. Our final report will be released in March 2020 with recommendations for the national service community — and that includes Peace Corps. Stay tuned! We also invite you to follow the commission on Facebook and Twitter via @Inspire2ServeUS and join the digital conversation on service by using the hashtag #Inspire2Serve.

Mark Gearan currently serves as the vice chair for National and Public Service for the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. He is director of the Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School and served as the 14th director of the Peace Corps from 1995 to 1999.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Fall 2019 issue.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleUnprecedented times, so we’ve set aside the standard playbook for WorldView magazine. see more

The evacuation of Peace Corps Volunteers serving around the globe is unprecedented. So is the way our nation is coming to terms with the truth that Black Lives Matter.

By Steven Boyd Saum