Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleOn October 19, 1960, MLK and student leaders were arrested. Why was King then sent to prison? see more

Nine Days

The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Win the 1960 Election

By Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

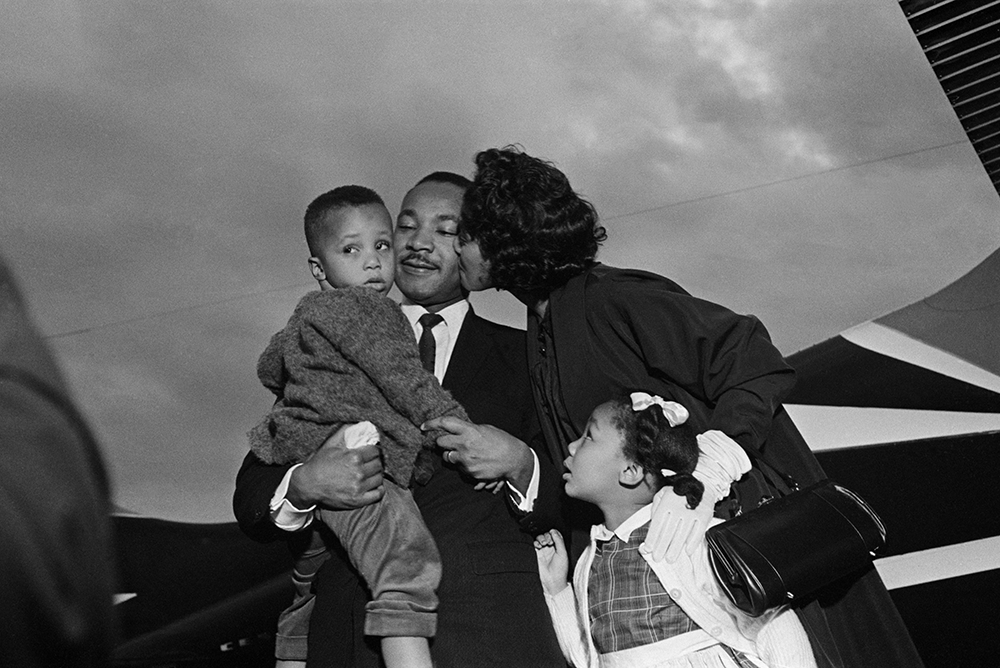

In October 1960, days after presidential candidate John F. Kennedy delivered an impromptu address at the University of Michigan that would spark the creation of the Peace Corps, a series of events were set in motion that loom large in the history of the civil rights movement. They arguably changed the course of the presidential election as well. On October 19, Martin Luther King Jr., at the urging of student leaders, joined a sit-in at Rich’s Department Store in Atlanta. Along with dozens of students, King was arrested and jailed; like the students, he refused to post bail. Unlike the students, he was not released days later. Instead, he was transferred to Reidsville State Prison.

Why? In May 1960, King was stopped by DeKalb police for driving with expired tags and was issued a $25 citation for driving in Georgia with an out-of-state license. He had been taking novelist Lillian Smith, who was white, to an appointment for treatment for breast cancer at Emory University Hospital; the car was hers. At a hearing in September, on the advice of his lawyer, King paid the fine and presumed the matter closed. What he didn’t know was that he was now on one year’s probation, and if he violated the terms he could be sentenced to 12 months’ labor in a work camp. As far as DeKalb County was concerned, taking part in the sit-in in October — willfully breaking the law — violated probation. Released from Fulton County Jail, King was turned over to deputies and later ordered by a judge to serve five months in prison.

Central to the Kennedy campaign’s work on civil rights were Sargent Shriver and Harris Wofford, who would go on to play founding roles in the Peace Corps.

Central to the Kennedy campaign’s work on civil rights were Sargent Shriver and Harris Wofford, who would go on to play founding roles in the Peace Corps. These two white men, together with newspaper editor Louis Martin, who was Black, convinced JFK to telephone Coretta Scott King, MLK’s wife. Bobby Kennedy, manager of the campaign, was furious when he found out. In Shriver’s recollection, Bobby “landed on me like a ton of bricks.” Bobby thought the sentencing for an out-of-state license was preposterous. But multiple Southern governors had warned the campaign not to support MLK. Bobby told Harris Wofford and Louis Martin, “You bomb throwers probably lost the election.”

Reunited with family: Martin Luther King Jr. after being released from Reidsville State Prison in October 1960. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Yet days later, it was Bobby Kennedy who broke the news that he had phoned the judge in the case and told him to get King out of jail — though Bobby claimed publicly that he only asked the judge about the right to make bond.

Not so well remembered was that before 1960, Richard Nixon was seen by many Americans, Black and white, as stronger on civil rights than JFK.

For Nine Days, father-and-son team Stephen and Paul Kendrick put together a day-by-day chronicle of events. Versions of this story have often been told. Not so well remembered was that before 1960, Richard Nixon was seen by many Americans, Black and white, as stronger on civil rights than JFK. It was the party of Lincoln, not a political tent that included racist Southern Democrats, that was deemed more likely to take civil rights seriously in the 1960s. Many Black Americans in Atlanta supported Republicans; Nixon was the one for whom Jackie Robinson was campaigning.

After King’s release from prison, he delivered a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church. He drew from the second book of Revelation, including the verse, “You have persevered and have endured hardships for my name, and have not grown weary.”

This review appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleOur commitment to empathy and justice — around the world, and here at home see more

Our commitment to empathy and justice — around the world, and here at home

By Glenn Blumhorst

Our nation is reeling. How could it not be? More than 100,000 Americans are dead from COVID-19. More than 40 million have filed for unemployment since mid-March. And last week we witnessed the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, at the hands of a white police officer.

These are not unrelated tragedies. And George Floyd’s death is only the latest in a terrible litany of unarmed Black men and women who have been killed. We condemn the actions that led to his death, just as we condemn discrimination and violence against all Black people — including members of the Peace Corps community.

The toll of coronavirus has hit black and brown communities particularly hard. So have job losses. And in a time of global pandemic, we’re faced once more with a brutal truth articulated years ago by Sargent Shriver, who founded the Peace Corps: “We must also treat the disease of racism itself.”

How do we do that? Fundamentally, those of us in the Peace Corps community embark on service as Volunteers to promote world peace and understanding. This is our world, right here. One where empathy and justice must guide us — as we head out into the world, as we bring it back home. Our commitment to that doesn’t stop at the border. As National Peace Corps Association Board Director Corey Griffin has often put it, “By living out Peace Corps values here at home, we’ll have a better society, one that honors and celebrates our differences.”

A moral issue

Friday marked the birth of John F. Kennedy, who famously offered the challenge: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” A crucial time to ask that question again.

And it happens that on May 30, 1964, Sargent Shriver, the first director of the Peace Corps, spoke of the challenge he saw facing America then: “Although poverty and injustice remain, we have today, for the first time, the legal and material resources to end them.”

So have we? No. But those words ring true in another respect. Put together Kennedy’s challenge and Shriver’s assessment all those decades ago. One thing we can do for our country now is seek — once and for all — to end racism. We need concerted and peaceful action. And, make no mistake, we need courage and hope in these dark times.

Shriver understood the challenge and the stakes. “Today’s central issue is a moral issue: the issue of commitment,” he said. “If we fail, it will be a failure of commitment.” We can eliminate unemployment and poverty, he said, and we can ensure security against the ravages of disease and old age, use science to benefit all people, and ensure that Black Americans can be “fully American.”

His words merit quoting at length:

These are not easy problems. I have seen the face of poverty and idleness in the mines of West Virginia. I have come face to face with racial hatred on the South Side of Chicago: Catholics stoning fellow Catholics on the steps of a church because they were Black. In the last few years, I have traveled five hundred thousand miles around the world seeing at first hand the deep barriers of culture, belief, prejudice, and superstition which divide us from our fellow man.

But I have also seen the power of commitment, the individual commitment of thousands of Peace Corps Volunteers doing more than any of us can realize to refashion our relationships to the rest of the world. The Peace Corps is proof that deeply committed individuals can have a profound impact on the most difficult and intransigent of problems. Fuller proof is found in the civil rights movement.

Shriver also understood the feeling of powerlessness when faced with enormous challenges.

What can we do about it? you ask. There is much you can do. For the need is not merely for laws or Presidential action, but for the self-organization of society on a large scale to solve the problems … Our books are full of good laws and regulations, but … hypocrisy and racial hatred and the apathy of decent citizens have made a mockery of American justice and equal opportunity.

We must now show that we have the personal commitment to use our wealth and strength in the construction of a good society at home and throughout the world.

As our friends at the Sargent Shriver Peace Institute note: When Shriver spoke of the idea of “self-organization,” he was calling for a community to organize and lead from within — and recognizing that big problems could be solved by strengthening understanding and collaboration on a large scale.

Returned Peace Corps Volunteers across the country are convening virtually to ask how we can act together to address racial injustice. I encourage you to join the conversation. To listen, and learn more about organizations you can work with for social justice. To raise your voice. And to help others do so.

You can help ensure underrepresented members of our communities have a vote. Here is a list of resources for those who want to help with voter registration — from HipHop Caucus to Rock the Vote. And contact your elected representatives; let them know this matters to you.

We should also take heed of these words by Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

Glenn Blumhorst is President and CEO of National Peace Corps Association. He served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala (1988-1991). You can read Sargent Shriver’s speech in full here.