Activity

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA tribute to decades of work by children’s author Mildred D. Taylor. see more

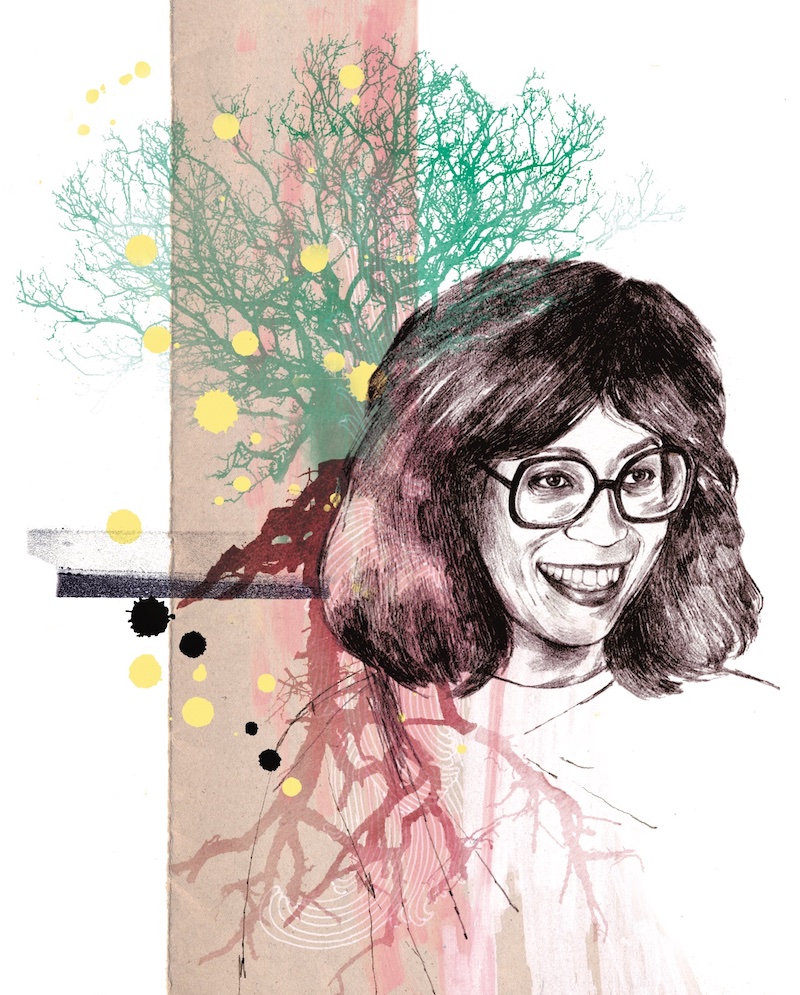

A tribute to decades of work by children’s author Mildred D. Taylor. This year, Peace Corps Writers recognized her with the Writer of the Year Award.

By John Coyne

Illustration by Montse Bernal

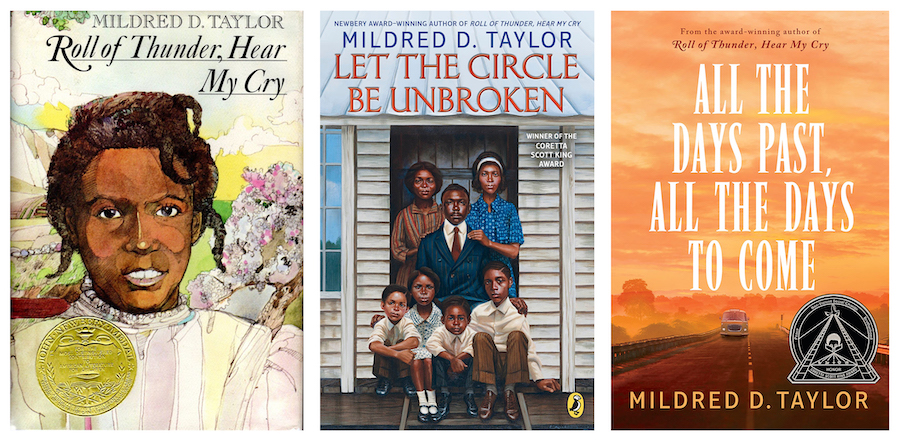

Mildred Delois Taylor is a critically acclaimed author of children’s novels. In 1977, she won the Newbery Medal, the most prestigious award in children’s literature, for her historical novel Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. It was the second book in a series of ten novels focusing on the Logan family, and portraying the effects of racism counterbalanced with courage and love. Her latest book, All the Days Past, All the Days to Come, published last year, is the final novel in the series.

Since receiving the Newbery Medal, she has won four Coretta Scott King Awards, a Boston Globe–Horn Book Award, a Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the PEN Award for Children’s Literature. In 2021 she received the Children’s Literature Legacy Award, honoring an author whose books have made a significant and lasting contribution to literature for children. In presenting the award, Dr. Junko Yokota said of Taylor’s storytelling, “It shows how courage, dignity, and family love endure amidst racial injustice and continues to enlighten hearts and minds of readers through the decades.”

Mildred Taylor was born in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1943. Her paternal great-grandfather, the son of a white Alabama plantation owner and a Black woman forced to serve him as a slave, became a successful farmer in Mississippi. His large extended family thrived despite the racism they encountered.

Her parents, Wilbert and Deletha, wanted their daughters to grow up in a less racist society. Mildred was only four months old when they, like thousands of other African American families, boarded a segregated train bound for the North.

Arriving in Toledo, Ohio, the Taylors stayed with friends until they earned enough money to buy a large duplex on a busy commercial street. This house soon became home to aunts, uncles, and cousins, all moving away from Mississippi in search of a better life.

“I learned a history not then written in books but passed from generation to generation on moonlit porches and beside dying fires in one-room houses, a history of great-grandparents and of slavery and the days following slavery; of those who lived still not free, yet who would not let their spirits be enslaved.”

Mildred stored in her memory the tales she heard as a child at family gatherings. Many of these stories would later become plots in her novels. In her author’s note to Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, Taylor acknowledged her debt to this family who generously shared stories of their history, and to her father in particular. “By the fireside in our northern home and in the South where I was born, I learned a history not then written in books but one passed from generation to generation on the steps of moonlit porches and beside dying fires in one-room houses, a history of great-grandparents and of slavery and of the days following slavery; of those who lived still not free, yet who would not let their spirits be enslaved. From my father the storyteller I learned to respect the past, to respect my own heritage and myself.”

Illustration by Montse Bernal. Originally commissioned for O The Oprah Magazine

In addition to the oral stories, books also played an important role in Taylor’s life from an early age.

“I can’t remember when I received the very first book of my own,” she says today, “but reading, at times, caused trouble. At night I would sit in the closet when I was supposed to have long been asleep. And I got into trouble during the daytime, too, when I would be reading in hiding when I was supposed to be doing my chores.”

In 1965, Mildred Taylor applied to be a Peace Corps Volunteer. Milly, as she was always known in-country, was sent to teach secondary school in the town of Yirgalem in southern Ethiopia. She was one of a large group of new PCVs to that rural location 260 kilometers south of Addis Ababa. She lived with another Volunteer; a woman older than herself who had previously taught overseas at a U.S. Army base. The two women became the best of friends.

“Reading, at times, caused trouble. At night I would sit in the closet when I was supposed to have long been asleep. And I got into trouble during the daytime, too, when I would be reading in hiding when I was supposed to be doing my chores.”

It was in Yirgalem that I first met Milly, when I was serving as associate Peace Corps director for Ethiopia. I remember her as someone who caused no trouble, made no demands, and was a silent observer of other Volunteers, some of whom in her town were real “characters” — but she never wrote about them in her novels.

What none of us knew was that Milly was already an accomplished writer. By the time she arrived in Ethiopia, she had completed her first novel. At the age of 19, she wrote Dark People, Dark World, the story of a blind white man in Chicago’s Black ghetto, told in the first person. Publishers were interested in the book, but Milly disagreed with the revisions they wanted, and the novel was never published.

Returning home from Ethiopia, she worked as a Peace Corps recruiter, and she also trained new Volunteers for Ethiopia. She then enrolled at the University of Colorado School of Journalism and earned a master of arts. While a graduate student, she worked with university officials and fellow students and structured a Black Studies program at the university.

In 1971, she moved to Los Angeles to write full time, and she supported herself by doing temporary editing and proofreading. She also married and gave birth to a little girl. Her life and career, however, were about to change. When she was offered a position to work as a reporter for CBS, she declined it, knowing her future was in writing novels, not reporting news. In 1973, she entered a contest sponsored by the Council on Interracial Books for Children. Her book, Song of the Trees, won first prize in the contest’s African American category and was published by Dial Books in 1975. The New York Times listed it as an outstanding book of the year.

This book, about the Logan family, was to be the first in a series of ten novels based on stories from Milly’s own family history. One of her best-known books, Let the Circle Be Unbroken, was nominated for the 1982 National Book Award and received the Coretta Scott King Award in 1983.

Having grown up immersed in family stories, Milly often revisited her great-grandfather’s house, built at the turn of the past century and without running water or electricity. Memories of those visits found their way into her Logan family stories, most notably Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, the 1977 Newbery Medal winner. Taylor’s stories reveal struggles, racial tension, and tragedy, as well as triumph, pride, and family honor.

In an interview published in Book Links, Milly talks about her family and the novels she has written about growing up in a Black family in the South.

“All of my books are based on something that happened to a family member or a story told by a family member, or they are based on something that happened to me when I was growing up,” she says.

“I write about history because I was very affected by it as a child. When I was in school, many people did not know about the true history of Black people in America. I wanted to tell the truth about what life was like before the civil rights movement.”

Milly Taylor is an example of someone who has made a difference overseas as a Peace Corps Volunteer and also here at home as a novelist.

Recently she wrote me that it was an honor to be included with so many fine writers who are former Peace Corps Volunteers. “Being in the Peace Corps was one of the greatest experiences of my life and I cherish the memories of my days in Ethiopia. So many times now I find myself wishing I could relive it all.”

Don’t we all, Milly. Don’t we all.

TOO REAL

Mildred Taylor’s honest depictions of racial injustice have inspired many readers over the years. Some who lived through the eras she writes of extol how the stories echoed their firsthand experience; others comment on how the books opened their eyes for the first time to the horrors of racism. Not surprisingly, that honesty has also brought a different kind of scrutiny. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry made the American Library Association’s top 100 list of banned and challenged books for 2000–2009. It came in at No. 66, a few below Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner and a few above Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

This essay appears in the special 2022 Books Edition of WorldView magazine.

John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962–64) is the author of more than 25 fiction and nonfiction books and is the co-founder of Peace Corps Worldwide.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleEldon Katter chronicles his time with the first group of Peace Corps Volunteers in Ethiopia. see more

POETRY SKETCHES

A PEACE CORPS MEMOIR

By Eldon Katter

Peace Corps Writers

Reviewed by Kathleen Coskran

Eldon Katter sketches with images and words alike. He had the foresight to chronicle his time with the first group of Peace Corps Volunteers in Ethiopia (1962–64) through short poems and drawings — both his and his students’. He had the fortune to be assigned to teach in Harar, Ethiopia — one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, the only walled city in Ethiopia, and now a World Heritage Site.

I don’t think many subsequent Volunteers received an engraved invitation from His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, but Katter did: for a dinner at the Messerate Palace on October 13, 1962, featuring French wine and Italian pastries.

This review appears in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of WorldView magazine. It is excerpted from a review that originally appeared on Peace Corps Worldwide.

Kathleen Coskran served as a Volunteer in Ethiopia 1965–67.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleSonja Krause Goodwin's extraordinary time in the early years of the Peace Corps see more

My Years in the Early Peace Corps

Nigeria, 1964–1965 (Volume 1)

Ethiopia, 1965–1966 (Volume 2)By Sonja Krause Goodwin

Hamilton Books

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Sonja Krause Goodwin had already traveled far from home, earned a doctorate in chemistry, and worked for six years as a physical chemist when she joined the Peace Corps. Born in St. Gall, Switzerland, in August 1933, she had fled Nazi Germany with her family and resettled in Manhattan, where her parents opened a German bookstore. Sonja entered elementary school without speaking a word of English.

Science is where she found her calling. She earned her bachelor’s in chemistry at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and her Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1957. After working six years in industry, she joined the Peace Corps and headed for Nigeria. She led the physics department at the University of Lagos until she and the other Volunteers had to leave the country in 1965 due to a politically motivated “university crisis.”

She was reassigned to teach chemistry at the Gondar Health College in Ethiopia 1965–66, a college that also served as the local hospital. On her return to the U.S., she accepted a position at RPI and taught there for 37 years, advancing through the positions of associate professor and professor, and retiring in 2004. These memoirs were published in fall 2021, shortly before Goodwin’s death on December 1, 2021.

Story updated May 2, 2022.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleRecognition for members of the Peace Corps community see more

Honors from the University of California, the Republic of Mali, Dartmouth College, and Bucknell University

By NPCA Staff

Maureen Orth | Colombia 1964–66

Maureen Orth received a 2021 Campanile Excellence in Achievement Award from the Cal Alumni Association, in partnership with the University of California, Berkeley Foundation, for pushing boundaries whenever possible. She is an award-winning journalist, bestselling author, and founder of the Marina Orth Foundation, which supports education in Colombia.

Melvin Foote | Ethiopia 1973–75

Melvin Foote received special recognition from the president of Mali this year: He is to be honored with the Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mali — the Knight of the Order of Mali, for a foreign national. Foote is the founder and CEO of the Constituency for Africa. As Mali’s ambassador to the U.S. wrote to Foote: “Your significant and long-standing contributions of time, energy, and leadership to promote relations between the Republic of Mali and the United States of America have been recognized and appreciated.”

Peter Kilmarx | Democratic Republic of the Congo 1984–86

Peter Kilmarx was recognized with the 2021 Daniel Webster Award for Distinguished Public Service by the Dartmouth Club of Washington, D.C., for his work with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Public Health Service, and Peace Corps. Kilmarx serves as deputy director at Fogarty

International Center at the National Institutes of Health.Ruth Kauffman | Sierra Leone 1985–87

Ruth Kauffman received Bucknell University’s 2020 Service to Humanity Award in recognition of her 30-year career in international women’s health and midwifery. She has served in eight countries through Doctors Without Borders. In 2016, she partnered with colleagues to open a cross-border birth center providing services to women in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. “Ensuring that women in diverse communities have equitable access to safe, natural birth is essential to improving reproductive health worldwide,” she says.

-

Communications Intern 2 posted an articleAn open letter from hundreds of returned Volunteers and three former U.S. ambassadors see more

An open letter from 350 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who have served in Ethiopia and Eritrea — signed by former U.S. ambassadors and more

By Jake Arce

AS BLOODSHED IN THE TIGRAY REGION of Ethiopia drew toward the end of its third month, more than 350 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers and a trio of former U.S. ambassadors issued an appeal to Congress asking for the U.S. to condemn the violence and demanding better humanitarian access, heightened protection of civilians, a U.N. investigation into human rights violations, and the lifting an information blockade. The returned Volunteers were joined by scores of former Fulbright fellows and other concerned citizens. They did not advocate for any political entity but “in support of human dignity.”

Violence in the region was triggered by an election in Tigray in November 2020 that the government of Ethiopia deemed unconstitutional. Fighting flared between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front and government forces, sending tens of thousands of people fleeing into neighboring countries. Now more than 2 million people have been displaced.

“We ask that the United States does not forget that its strongest allies are not simply constituted of politicians in Addis Ababa,” the letter states. “They are also the students, teachers, farmers, and healthcare workers that Peace Corps Volunteers collaborated with in the urban and rural communities currently embroiled in turmoil.”

There have been extensive reports of civilians killed, tortured, or internally displaced, as well as destruction of infrastructure, including health clinics, which are crucial during a deadly COVID-19 pandemic. In late March the prime minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, confirmed the presence of Eritrean troops in Tigray, with many organizations reporting human rights abuses — including extrajudicial killings and the ransacking of Eritrean refugee camps by these forces.

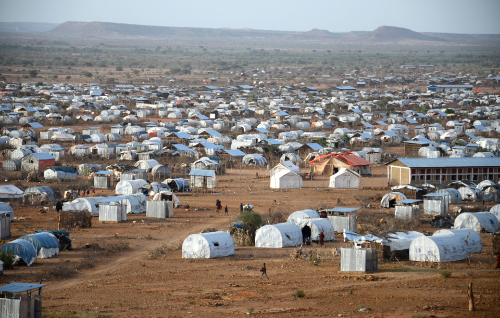

Mother and child, refugees in Sudan: some of the more than 2 million people displaced by violence in Tigray. Photo by Nariman El-Mofty / Associated Press

The letter was written by returned Volunteers who served in Ethiopia and Eritrea and sent in February. It urged humanitarian aid to Tigray amid reports of starvation. Over 5 million people remain food insecure; famine stalks.

“We ask that the United States does not forget that its strongest allies are not simply constituted of politicians in Addis Ababa,” the letter states. “They are also the students, teachers, farmers, and healthcare workers that Peace Corps Volunteers collaborated with in the urban and rural communities currently embroiled in turmoil.”

In March, the U.S. State Department declared it was looking into cases of human rights abuse in Tigray and offered additional humanitarian aid in response to the conflict.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleCOVID-19 is not the first time Ethiopia has dealt with public health concerns see more

Another time, another place, another virus

By Barry Hillenbrand

”Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia” is a hefty and important book that rightfully deserves an honored place on any shelf of serious books about epidemiology and public health. The book tells the tale of the work that some 73 Peace Corps Volunteers did in the 1970s with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Smallpox Eradication Program (SEP), a massive project that ultimately eliminated smallpox from the world.

This serious story is served up with large dollops of nostalgia, humor, delightful tales of daring, and loads of information about fighting infectious diseases, which — as it turns out in these times of the coronavirus — makes the book very contemporary. Even useful.

By the early 1970s, WHO’s goal of eliminating smallpox around the world was nearly accomplished. The SEP had battled down smallpox in all but a handful of countries. Ethiopia was one where the disease had been stamped out in major population centers, but it still raged in the remote corners of the country where there were few roads and meager medical infrastructure. Peace Corps and the WHO agreed to send Volunteers into these remote areas to root out the disease.

In late 1979, Ethiopia — and the world — was declared smallpox-free.

This book is made up of essays by the Volunteers who served in the SEP, plus contributions from Dr. D.A. Henderson and Dr. Ciro de Quadros of WHO. Inevitably there is a bit of repetition in the stories of broken Land Rover axles, tent-invading ants, the administration of massive numbers of vaccinations in crowded market places, impassable roads, and parasite ravaged guts. But the sum is far greater than the parts. This is a rich narrative history of a wildly successful and difficult Peace Corps project. These guys — and, yes, they were all men — were what we ordinary Peace Corps Volunteers called “real Peace Corps.” Peace Corps staff called them “Super Vols.” And they were.

Edge of the Gishe plateau: from left, SEP team members Ali Abduke, Lewis Kaplan, Girma, October 1973. Courtsey Warren Barrash.

The program used classic public health tactics: Find the remaining cases of the disease via intensive search and surveillance of the far corners of the country, then isolate and contain the disease carriers behind circles of vaccinations. No need to vaccinate the entire population of the country (though in the end SEP administered more than 17 million doses), just areas around where an outbreak was taking place, to create a barrier against its spread.

Sounds easy, but it wasn’t. Ethiopia is the second-largest country in Africa, but at the time had only 5,000 kilometers of what might be generously classified as all-weather roads. Over 80 percent of the population lived more than 30 kilometers from these roads. There are highlands with 13,000-foot mountains and sweltering deserts that sit below sea level. And in between are endless gullies, gorges, escarpments, and ridges to traverse.

Logistics were a nightmare. WHO handed out new Land Rovers to many PCVs in the program; they carried supplies to the jumping-off points, loaded gear on mules and, if they were lucky, also rode mules up and down escarpments in search of smallpox cases. Once, when there were no mules to rent, a PCV suggested to WHO headquarters in Addis that WHO buy a couple of mules for SEP use. The request was sent all the way up to WHO’s Geneva headquarters, where it was denied. The Volunteer, disappointed but determined, ponied up his current month’s living allowance and bought a pair of mules himself, reselling them later after the project was finished.

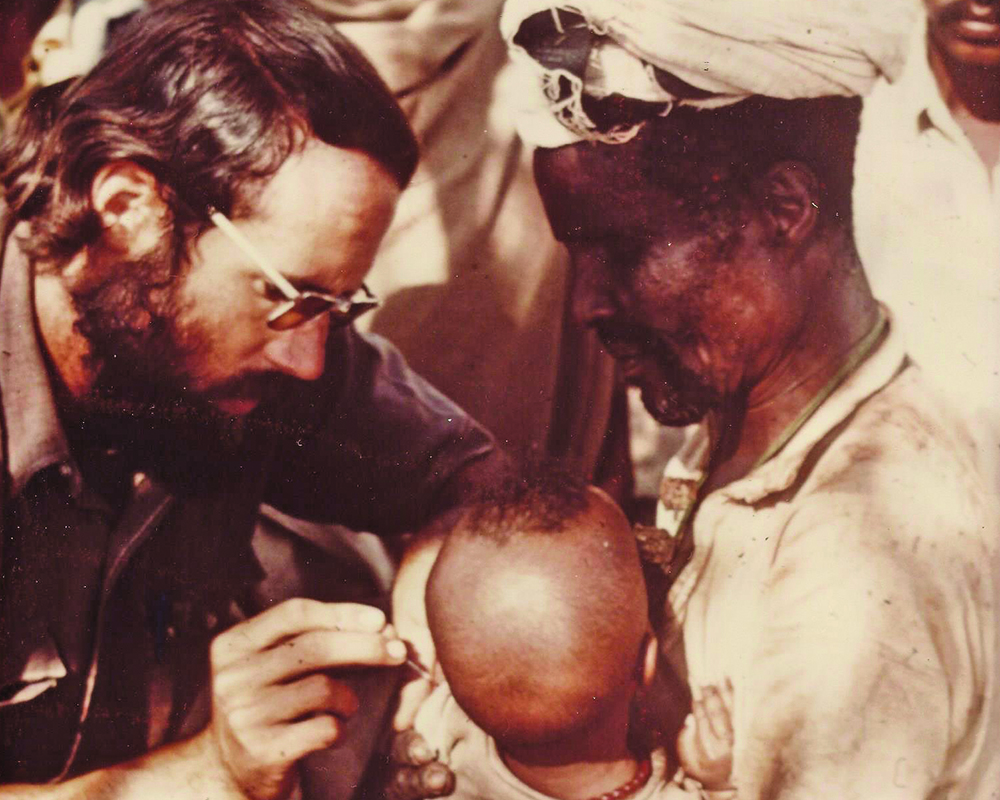

Gemu Gofa: A child receives a smallpox vaccination from Volunteer Michael Santarelli, 1973. Courtsey Mark Weeks.

Mostly they walked: hours and hours, from village to village over footpaths that took them to the far reaches of Ethiopia. They carried cards with pictures of smallpox victims, asking villagers if they had seen any cases. The PCVs hauled tents with them, but often they slept on the floors of regional health centers or, more often, in the mud tukul (round hut) of villagers who offered them welcome and shared food with them. The generosity and friendliness of these villagers — often the poorest of the poor of Ethiopia — was boundless and fills the PCVs’ writings, 50 years later, with a profound sense of admiration and affection.

While logistics were a major problem, the PCVs had to contend with other subtle and often more worrisome issues. Getting permission to vaccinate from local officials, in the form of a letter adorned with official stamps in that obsequious — and very essential — purple ink beloved by Ethiopian bureaucrats, was time-consuming and required great patience. Even with the letter from government officials in hand (some PCVs also carried a copy of a letter from Emperor Haile Selassie himself urging citizens to get the vaccination), finding cases and convincing people to be vaccinated was a laborious task.

Some ethnic groups in Ethiopia were more receptive to vaccination than others. The Amharas of Gojjam and the central highlands, for example, were cool to the idea of letting foreigners jab them with the special WHO-designed smallpox vaccination needle. They required extensive persuasion by the PCVs, even when smallpox was maiming and killing people in the villages. Other Ethiopians eagerly accepted these strange foreigners, mistakenly called “doctors.” In some places when word went out that vaccinations were on offer, hundreds of villagers showed up and pressed forward with such eagerness to get their vaccinations that it was difficult to maintain order.

Market day: Senyo Gebaya, northwest of Addis Ababa in Gishe woreda (district), May 1974. Courtesy Warren Barrash.

As for that needle: It was a two-pronged affair, and each cost less than a quarter cent to produce. The bifurcated tip was dipped into a bottle of vaccine; a drop would stick between the forks. The vaccinator would then make multiple punctures in the skin of the person being vaccinated.

Some PCVs worked alone, mastering not only the difficult terrain and stubborn mules, but the mélange of languages and customs. Most traveled with Ethiopian coworkers — public health professionals often called “dressers” or “sanitarians.” They shared the difficult trails, administering the endless rounds of vaccinations. Often they were able to provide interpretation into the other languages of Ethiopia. And they were good company and became close friends with the PCVs. Stuart Gold writes: “The WHO and Peace Corps workers of SEP… did contribute to the eventual demise of smallpox in Ethiopia, but in fact, it was the nationals on the ground, the translators, the helpers, and the sanitarians who worked alongside us who deserve most of the credit. Without them, we would have been unable to navigate the nuances of the Ethiopian culture and traditions.”

In their individual essays, the PCVs unfailingly pay tribute to the two beloved and admired WHO leaders of the project: Dr. Donald A. (D.A.) Henderson, director of the WHO’s Global Smallpox Eradication Program, and Dr. Ciro de Quadros, the charismatic and tireless WHO epidemiologist in charge of field operations in Ethiopia. These two WHO professionals not only led the successful fight to eradicate smallpox in Ethiopia, but taught the inexperienced PCVs their fieldcraft. The book is dedicated to them.

“The Smallpox Eradication Program in Ethiopia.” Mural by Ato Tesfaye Tave, 1975. Mural courtesy the Institute of the History of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University.

By 1973, smallpox was on the run, even in remote areas, but Ethiopia was undergoing profound changes. A severe famine struck the country’s central highlands. A few PCVs left the smallpox project and began working in famine relief. In 1974 Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown and an autocratic, communist-leaning government, the Derg, took power. Peace Corps withdrew from the country. WHO hung on, secured the support of the new revolutionary government, and ultimately finished the smallpox project using government helicopters and highly effective Ethiopian health workers, many of whom had worked with the PCVs. In late 1979, Ethiopia — and the world — was declared smallpox-free.

As for those young PCVs who had arrived in Ethiopia clutching their newly minted degrees in English and history and left the country after two years of service as battle-

tested public health workers, many of them returned to the United States to get advanced degrees in public health. Some even went to work again with WHO. Michael Santarelli, who once vaccinated Mursi warriors he encountered while traveling, participated in WHO’s smallpox eradication project in Bhola Island, Bangladesh, where the last recorded outbreak in Asia took place. Once a Super Vol, always a Super Vol.

Barry Hillenbrand was a Volunteer 1963–65 in Debre Marcos, Ethiopia, where he taught history at a secondary school. As a summer project, he gave TB test injections in the central market in Harrar, Ethiopia. After Peace Corps, Hillenbrand became a correspondent for Time magazine. His essay first appeared on PeaceCorpsWorldwide.org.

Eradicators and Contributors

Writing the book “was truly a group effort that required a bit more than five and a half years to complete,” says lead editor James Skelton. And, as he told the Houston Chronicle last year, “It became clear to me pretty early on that these guys in the field were heroes.” An attorney in Houston, Skelton knew the journals that most Volunteers kept could help provide raw material. But giving the material shape took work. D.A. Henderson provides the opening context with “Global Eradication of Smallpox.” Ciro de Quadros wraps things up.

Here’s the Peace Corps team, along with their years of service:

Warren Barrash (Malaysia 1970–72, Ethiopia 1973–74)

Gene L. Bartley (Ethiopia 1970–72, 1974–76)

David Bourne (Ethiopia 1972–74)

Peter Carrasco (Ethiopia 1972–74)

Stuart Gold (Ethiopia 1973–74)

Russ Handzus (Ethiopia 1970–72)

Scott D. Holmberg (Ethiopia 1971–73)

John Scott Porterfield (Ethiopia 1971–73)

Vince Radke (Ethiopia 1970–74)

Michael Santarelli (Ethiopia 1970–73)

Alan Schnur (Ethiopia 1971–74)

James Siemon (Ethiopia 1970–72)

James W. Skelton Jr. (Ethiopia 1970–72)

Robert Steinglass (Ethiopia 1973–75)

Marc Strassburg (Ethiopia 1970–72)

“Humanity’s Victory”

In May 1980, the World Health Assembly declared: “The world and all its peoples have won freedom from smallpox.”

For 3,000 years smallpox exacted a terrible toll; in the 20th century it killed 300 million. In May 2020, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus observed: “As the world confronts the COVID-19 pandemic, humanity’s victory over smallpox is a reminder of what is possible when nations come together to fight a common health threat.”

Key to success: an effective vaccine and a concerted effort to help people around the world. In strictly economic terms, the $300 million invested over a decade saves more than $1 billion a year in health costs. That does not measure the value of lives saved and suffering averted.

-

Communications Intern posted an articleA conversation we’ve had again and again. Here are some ideas, insights, and hard truths. see more

Recruitment, support — and what next? It’s a conversation we’ve had again and again. Here are some ideas, insights, and hard truths.

ON SEPTEMBER 15, 2020, THE CONSTITUENCY FOR AFRICA convened a group of past, present, and future Peace Corps leaders for the annual Ronald H. Brown African Affairs series. It’s a timely and needed conversation — with all Peace Corps Volunteers evacuated from around the world because of COVID-19, and as our nation grapples with pandemics of coronavirus and systemic racism.The conversation was moderated by educational consultant Eldridge “Skip” Gilbert, who served as a Volunteer in Sierra Leone (1967–69). Edited excerpts here. You can also watch the full video.

Introduction

Melvin Foote: I served in Eritrea and Ethiopia in the early ’70s. Peace Corps is the reason I’m doing what I am today. Constituency for Africa is a policy advocacy organization; we help to educate Americans about Africa, improve cooperation and coordination between organizations, and help shape U.S. policy toward Africa.

Now Peace Corps has gone through the trauma of evacuation of Volunteers worldwide, trying to figure out when and how it will return to the field. We want to increase the number of African Americans and Americans of African descent in Peace Corps. It comes at an interesting time for our country, as Black Lives Matter and the forces of coronavirus have taken over our lives. How do we strengthen the Peace Corps going forward?

That is what this conversation is about.

Melvin Foote, Founder & CEO, Constituency for Africa (Ethiopia 1973–75)

Each One, Reach One!

Darlene Grant: I’m speaking from Birmingham, Alabama, where I am steeped in my family’s and our nation’s history — of overcoming overwhelming odds, injustice, and disparities to fulfill our ancestors’ wildest dreams. We know what it means that we’re stronger together. That it takes a village to help individuals realize their full potential. That is what we have to offer the Peace Corps. I have six points to make.

One, focus primarily on the health, safety, and security of Volunteers. Peace Corps partners with communities abroad to develop sustainable solutions to the world’s most pressing problems and challenges. It’s critical to empower more African Americans and Black-identifying individuals to drive the narrative of who they are — Volunteers who can show the strength, resilience, ingenuity, beauty, richness of our culture in the spaces where they walk, live, and serve. It is critical that African American Volunteers work collaboratively with Latinx, white, Asian, and other identifying Volunteers, so that when they return to the United States, they are able to effectively communicate across differences. To mobilize diverse communities, form coalitions, make the U.S. — and the world — a better place.

Two, in today’s world, a college degree is not enough to impact socioeconomic mobility of oneself or one’s family. Peace Corps service pays dividends. We must better communicate those dividends so that our Black-identifying and African American sisters and brothers can communicate to their families, schools, businesses, churches, mosques the value of leaving to come back stronger, bigger, badder, leaner, meaner. Peace Corps offers a significant resume value, on-the-ground international development experience, foreign language immersion, small grant writing and implementation skills. It offers interaction with State Department, USAID, United Nations staff, and other communities — and opportunity to take the Foreign Service test. I was 50 years old at my mid-service, and I was thinking, “Man, if I had known about all of this when I was preparing to graduate from college, where would I be today?” So I’m making sure my grandkids know — and nieces, nephews.

My first leave of absence from Mongolia as country director I visited my niece’s first grade class. I was a secret reader of the day. I read a Halloween story. Then I held up a Mongolia flag, told stories of Mongolia to a bunch of first graders in a predominantly white elementary school in Birmingham, Alabama. Then I invited them to go home and tell their parents they were going to grow up to join the Peace Corps. That poor first grade teacher’s eyes got so big — she thought I was starting a ruckus she would not be able to control! But that is what we must do: Start early and often in the schools.

Three, in many African American and Black-identifying families — particularly in lower income communities — if you have earned a college degree, you are the family’s bootstraps, by which families have a chance to see a bigger world, a broader view, a hope for different tomorrow.

The role of African Americans in post-pandemic U.S. Peace Corps is to describe and design the doors for others to walk through.

Four, the role of African Americans in post-pandemic U.S. Peace Corps is to describe and design the doors for others to walk through.

Five, the pandemic has highlighted racial and socioeconomic inequities in our country. It has done so in countries abroad as well. They must see a more diverse volunteer corps to better understand and to better grow their own worlds.

Finally, this pandemic and everything else going on have high-lighted global interconnectedness — and with that an increased need for people, for African Americans, who can effectively and sensitively navigate cross-cultural difference for the purpose of building a just and equitable world and systems, a just and equitable peace.

Dr. Darlene Grant, Senior Advisor to Peace Corps Director (Cambodia 2009–11)

Skip Gilbert: I would like to add a little bit more to that. Not only do we need to reach out and “each one, reach one,” but it's wonderful that we have the opportunity of “each one teaching one.” So we can learn to not only reach out for contact purposes, but we have the responsibility to teach as well.

Recruitment

Dwayne Matthews: When I was in the application process, I asked, “What is Peace Corps doing to gain African Americans?” I wrote a list of things I wanted to do. I didn’t find out about Peace Corps until going to community college. I was watching an episode of “A Different World” and heard the character Whitley say, “Well, why don’t you just ship me off to the Peace Corps?” That prompted me to look into it.

When sitting in the village, I knew I wanted to target Historically Black Colleges and Universities. My first event as a diversity recruiter was doing an HBCU tour up and down the East Coast and the South coast. From there, I did the HBCU barbershop tour: 23 barbershops gave me the platform. We have to be more creative in the ways that we’re attracting folks.

I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. Peace Corps just wasn’t a conversation. My folks didn’t travel.

I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. Peace Corps just wasn’t a conversation. My folks didn’t travel. My dad’s a truck driver, my mother’s a housewife.

Now, in this COVID-19 pandemic and racial pandemic, I was able to speak with the Peace Corps powers that be, and we are in the process of creating an HBCU video where we’re talking to returned Volunteers who graduated from HBCUs about their experiences — how Peace Corps has set them up for their life.

Dwayne Matthews, Office of Peace Corps Diversity Recruiter (Malawi 2013–15)

Clintandra Thompson: Senegal is predominantly Muslim, predominantly Wolof speaking. My community was Catholic and Sarare. I was in my language group with one other Volunteer, a white woman from Utah. I remember her dad sending cards and letters at least twice a week. She got one for administrative professionals day, for Veterans Day, for Tuesday! Her parents were very supportive of her service.

My parents were a little lukewarm. When I saw the support white Volunteers had from their community — in the way of care packages, visits, sponsored trips to other places, social media, phone calls — I said to myself when I returned, There’s definitely something we can do to lift ourselves up. I reached out to RPCV friends and asked if they would help me send letters, care packages, make calls to Volunteers in service. I started out small on Facebook and was overwhelmed with the response; there are way more current Volunteers who wanted to be matched with a Black RPCV.

I started the Adopt a Black Peace Corps Volunteer exchange to help and encourage Black Volunteers, to allow them an opportunity to reach out to Black RPCVs who’ve been there.

I started the Adopt a Black Peace Corps Volunteer exchange to help and encourage Black Volunteers, to allow them an opportunity to reach out to Black RPCVs who’ve been there — who know what those slights and comments might sound like, what it’s like when your community kind of shuns you, what it feels like to be the only American for miles and miles and hours and hours of travel. The Adopt a BPCV exchange has been around since 2015. I usually gear up in September in anticipation for sending out a Halloween card, Thanksgiving card, Christmas card, Christmas care package.

Clintandra Thompson, Communications Professional; Creator, Adopt a Black PCV Exchange (Senegal 2012–14)

Why Peace Corps?

Harris Bostic II: After a decade of swimming in all things Peace Corps — as a Volunteer, agency employee, and NPCA board member — I stayed ashore for awhile. Now as the waters again beckon for help with diversifying this 60-year-old organization, I’m ready to dive back in.

The years I spent in Africa as an advisor to a microcredit program and local Guinean small businesses have directly impacted my career, my personal life — and, frankly, my mere being. The Peace Corps was great for me. I do admit that it is not for everyone. But it certainly should be a viable option for more Blacks than it is now.

Shortly after I concluded my service, I landed a position with the Atlanta Olympic Organizing Committee for the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games. My boss chose me from a large number of applicants because of my Peace Corps experience: having a vast knowledge of the world beyond U.S. borders, the ability to embrace the unknown, push through ambiguity, work with limited direction and guidance, and continually learn about oneself and others. I became director of the 54 African Olympic National Committees, then advanced to the office of the chairman, Ambassador Andrew Young, where we were instrumental in negotiating South Africa’s return to the Olympics after a 30-year sanction due to apartheid.

At the Peace Corps agency I participated on many task forces. The “How to Quantify the Peace Corps Service” task force was incredibly important, but it lost steam due to the Peace Corps five-year rule, continual turnover, and loss of institutional knowledge. Today I challenge the agency, NPCA, and RPCVs, to come together and create crisp messages on all the salient reasons to join the Peace Corps — and benefits of service that target specific audiences: Blacks, folks from lower socioeconomic levels, people of color, etc.

Today I challenge the agency, NPCA, and RPCVs, to come together and create crisp messages on all the salient reasons to join the Peace Corps — and benefits of service that target specific audiences: Blacks, folks from lower socioeconomic levels, people of color, etc.

Career and grad school recruiters scour resumes, applications, and essays in search of various experiences. Often they see military service, an MBA, law degree, formal sports experience — and they associate discipline, decision making, critical thinking, teamwork, striving for excellence. Recruiters should see Peace Corps and think of all the core competencies associated with it.

Another call-to-action: Consider rebuilding the Peace Corps to attract Blacks and those from lower socioeconomic levels, who often just can’t afford to join the Peace Corps. They have college loans, credit card debt, need to support families back home. Unlike the military, the Peace Corps is unreachable — and sometimes seemingly more suitable for whites and privileged individuals. Allocate budgets to support those at lower socioeconomic levels so they can see Peace Corps as not only tenable but viable. Market and package Peace Corps service in such a way to attract Blacks by lifting up the quantifiable benefits of Peace Corps service.

The goal is for Peace Corps to assemble at the same table a group of both likely and unlikely allies — to work toward identifying solid benefits of service; quantifying, or translating them to understandable competencies; then market and package them into sellable traits and attributes that recruiters value and seek, especially among people of color, and from diverse backgrounds. Imagine what a group of RPCVs — business and community leaders, media, social scientists, academics, and changemakers — could accomplish by putting their heads together and brainstorming how the agency can not only quantify what it means to serve in the Peace Corps, but also give every PCV and even parents the proof that their service mattered.

Harris Bostic II, Strategic Senior Advisor & Client Services, Tides (Guinea 1988–91)

Anthony Pinder: Peace Corps has run through the veins of my understanding of what a global citizen is. I started as a Volunteer, came back to the agency as a country director in Central Africa and Equatorial Guinea, then came back to Washington as a national director for minority recruitment.

Removing barriers for underrepresented communities and creating a more just and equitable Peace Corps — we have always been concerned with that. It’s not enough to be concerned about increasing numbers. What are we going to do when we get them in the pipeline?

Removing barriers for underrepresented communities and creating a more just and equitable Peace Corps — we have always been concerned with that.

In the Office of Minority Recruitment, the first thing was change the name to the Office of Minority and National Recruitment Initiatives. I was given some university programs as well; you got to have tools in your toolkit. I did not want to just be the diversity guy. I wanted to have more juice among my own communities as I moved around the country and helped manage 11 regional recruiting officers.

I have worked in other spaces where the robustness of the folks in leadership positions was absent. And it’s awkward to bring up questions and strategies that benefit a particular community when certain people aren’t at the table. We were able to go into the HBCUs and negotiate awesome, big events, not just for minority recruitment, but for the agency. The first group of volunteers we sent to South Africa was on my watch. We did a dramatic sendoff in Atlanta, at Morehouse College, and also at Emory at the Carter Center.

Representation is important — as is supporting diversity at the country director level. As we talk about increasing recruitment of people of color, Black folks in particular, what happens when they get in country? Will there be advocacy for the difference that they bring, for the ingenuity and the wonderful things that make their experiences so rich — also for so many people alongside them? Look at what it takes for the successful completion of the volunteer experience, as well as leadership positions within the agency. This conversation is not a new one.

We’ve talked about the awkwardness of a five-year rule. Why is it, as one of the few minority directors of Peace Corps, as a country director, I’ve never gotten a call from Peace Corps? I have leveraged the awesome experience that Peace Corps was into a career in higher ed and other areas. We should know who each other are, the strengths and resources we possess, so another person following Dr. Grant does not have to start from scratch trying to identify stakeholders.

We should not have to revisit this topic again.

Dr. Anthony L. Pinder, Associate Vice President of Internationalization & Global Engagement, Emerson College (Ecuador 1987–90)

Skip Gilbert: One historical footnote: I also had a wonderful Peace Corps experience. And from that time until now, we've only had two African American Peace Corps directors. One, Dr. Carolyn Payton. And the other person, who is on this call, is Aaron Williams. Now Aaron Williams and I worked on an Office of Minority recruitment, under the leadership of one C. Payne Lucas. He and the late Dr. Joseph Kennedy were personal mentors to myself, and certainly others — among them Aaron Williams.

Coming Home

Marieme Foote: Peace Corps is almost in my blood. My mother is Senegalese and grew up in Senegal, surrounded by Peace Corps Volunteers, where she learned English and then came to the U.S. to pursue her graduate degree. My father was a Volunteer. Before that, he had no understanding of Africa as a whole. His career has been shaped by it. This has transformed their lives, and other Black lives across the world, and has transformed my own.

I’m still reeling from the difficulty of being pulled suddenly from Benin. With the reality of COVID-19 in the U.S., I’ve seen Volunteers going through homelessness, unemployment, lack of health insurance. COVID exposed a wound that hadn’t really been addressed. As Volunteers, we were rapidly trying to adjust to the reality of Blackness within the U.S. Within weeks of getting back, after quarantine, I was on the streets, protesting in front of the White House.

Peace Corps does have the capacity to transform lives, which is why it’s so important that we make sure that when Black Volunteers do return, they have support they need.

African Americans are disproportionately impacted by socioeco-nomic issues in the U.S. For many Volunteers, what is provided in terms of support when returning is not enough. Evacuees are facing issues with paying for health insurance or paying for their Close of Service medical exam and not being reimbursed. If you don’t have the money in the first place, how do you even pay for it?

Peace Corps does have the capacity to transform lives, which is why it’s so important that we make sure that when Black Volunteers do return, they have support they need.

Marieme Foote, Advocacy & Administrative Support Associate, National Peace Corps Association (Benin 2018–20)Rahama Wright: In Mali I served at a community health center. I also started working on developing cooperatives and small and medium enterprises. I was so impacted by my experience — seeing many women in my community struggling to care for themselves and their children. And I became obsessed with learning about making shea butter. When I came back to the U.S., I launched Shea Yeleen with a goal of helping women who make this amazing product bring it to the U.S. market in a way that was sustainable.

My parents met when my dad did the Peace Corps in Burkina Faso in the ’70s. I grew up in upstate New York in a family where I knew I would do Peace Corps. But I did not know the impact it would have: changing everything I thought about the continent of Africa, about people who lived in rural communities — experiencing what they were because of global social, economic, and political issues outside their control.

We have been given tools and experiences as Volunteers that we can use to make sustained, longterm impact in communities we serve. We have the knowledge and cultural competencies that a lot of Americans don’t. Most Americans don’t have a passport.

For Peace Corps, that means centering the role and contributions of Black and Brown people — not in a “we want to support diversity and inclusion by bringing more people to the table” — but really building an entirely new table.

Now, what we’re dealing with in terms of Black Lives Matter and COVID: The humanity of Black and Brown people is under attack not only here in the U.S. but globally. We have to rise to the occasion and say, “We’re not going to allow the things that we’re seeing without taking a stand.” That is so important, especially when we’re thinking about the future of Peace Corps. Everyone wants to build back better. For Peace Corps, that means centering the role and contributions of Black and Brown people — not in a “we want to support diversity and inclusion by bringing more people to the table” — but really building an entirely new table. We need to reimagine Peace Corps.

Rahama Wright, Founder & CEO of Shea Yeleen Health & Beauty Company (Mali 2002–04)

It’s About Ubuntu

C.D. Glin: For me, this conversation is about Ubuntu: “I am, because we are” — because of this community. Because of Tony Pinder leading minority and national recruitment, because of Harris Bostic in San Francisco as regional recruitment director. From being in the first Peace Corps Volunteer group that showcased diversity as a strength to a new South Africa: 32 volunteers — four African Americans, four people identified as Latinx, five people over 55, five Asian Americans. Having an African American country director, being greeted by the Mission Director to South Africa and the ambassador being African American men — Aaron Williams and James Joseph.

“Why are we still having this conversation?” We’re having this conversation again, and again. I went to South Africa in February 1997. It was a transformational time for our country but also for South Africa, with a democratically elected president who had battled back the racial oppression of apartheid. That historic moment was an opportunity to showcase the America that we all are — people of different backgrounds coming together for a cause.

That entry point into Peace Corps opens up the world. But if we as people of color, as African Americans, are not part of that, the rest doesn’t happen. Looking at foreign assistance and national security and diversity in all its forms: 189 Americans are serving as U.S. ambassadors. Seven are people of color: three African Americans, four people who identify as Latinx. Many in the State Department and foreign service, where did they start their careers? Peace Corps. We’re not in the pipeline if we’re not being recruited by people like Dwayne, supported by people like Dr. Grant.

That entry point into Peace Corps opens up the world. But if we as people of color, as African Americans, are not part of that, the rest doesn’t happen.

There was a full court press at the agency from the mid ’90s to early 2000s to recruit diverse volunteers. This was beyond race and ethnicity; this was ability, people over 50. There was a real intentionality. We lost some initiatives because they were never institutionalized.

People who are not traditional Volunteers — they’re not looking for adventure, they’re looking for a way to enhance their professional portfolio: the Foreign Service exam; universities looking for returning vol-unteers in the Peace Corps Fellows Program, in the master’s international program; a leg up in international development work. These are critical to tell people who are nontraditional recruits, predominantly African Americans, who come from places that represent and sort of look like some places where we are sending Volunteers.

When I arrived in my community in South Africa, there was a welcome: majorettes and a band at the school where I was going to serve. I had studied U.S. foreign policy toward Africa at Howard University, I’d been a Foreign Service intern in Ghana. I got to South Africa and knew this community was waiting for me. The Land Cruiser pulled up and I hopped out, and everyone was still looking around and looking over me and almost through me — because I wasn’t the American that they were waiting for. I didn’t look like the volunteer they were told they were going to get. Just by showing up, I knew I was going to transform the way that they thought about the U.S. I took it as a challenge. This is an opportunity for us as people of color, as African Americans, to show up, to represent.

I saw examples of what Peace Corps could do for careers by those who mentored me. I’m grateful to be “a success story” because of all those who’ve come before me — and to have reached back as I climbed. When I see Curtis Valentine on the chat, I remember a call from the country director in South Africa, Yvonne Hubbard, saying there’s a young brother here who’s a Morehouse man who wants to talk to you. Curtis Valentine has gone on to Harvard and become a leader in education throughout the state of Maryland.

I lead the U.S. African Development Foundation. Almost half of our staff are former Peace Corps Volunteers. The foundation, second to Peace Corps, is probably the government’s best kept secret.

It’s our duty to use our experiences to make young African Americans more aware of opportunities Peace Corps can provide. It’s incumbent upon the agency to ask us to do more.

The realities of today are not unlike the past. But what got us here, where we have so many success stories — they need to be leveraged. When I was a Peace Corps diversity recruitment specialist, it was my job to think about successful African Americans who had done Peace Corps. I got to know Ambassador Johnnie Carson, returned Volunteer, three-time ambassador, and an icon in the Foreign Service, now a mentor to me. After volunteering on the Obama campaign and leading the transition team at Peace Corps, to join the staff of Aaron Williams as the second African American, first African American male, to lead the Peace Corps—to focus on global partnerships and intergovernmental affairs — this was a true honor.

It’s our duty to use our experiences to make young African Americans more aware of opportunities Peace Corps can provide. It’s incumbent upon the agency to ask us to do more — give back in new ways, such as Adopt a Black RPCV. There is a recruitment issue, a pipeline issue, a retention issue. We also want to focus on advancement and leadership. It is about the intentionality that we need to bring. Let’s be innovative — and institutionalize the initiatives — so 10 years later, we aren’t having the same conversations again.

C.D. Glin, President of US African Development Foundation (USADF) (South Africa 1997–99)

Q&A

Skip Gilbert: What policies would you implement to increase African American presence in this new Peace Corps?

Dwayne Matthews: I was looking at an old Ebony magazine from 1978, with Mohammed Ali on the cover. It had Peace Corps Director Carolyn Payton inside — talking about the same thing we’re talking about today. But she had a three- or four-page ad about African Americans and the need for them in Peace Corps.

I don’t know where that money is being allocated to. I do know that if they’re trying to target us, the budget needs to be bolstered.

Skip Gilbert: We have a marvelous opportunity to engage in a new dialogue, which will allow us to help create that new Peace Corps.

Anthony Pinder: It’s not about creating safe spaces, but brave spaces. I had some really courageous supervisors; if you’re going to empower me to do something, I need you to advocate for me, even if I do something wrong.

There needs to be a holistic strategy — people empowered to be great, and hired because of their innovation, genius, courageousness. When you have directors and all levels throughout the organization empowered, so we are not in isolated roles, we don’t have to have major conferences about inclusive excellence; it’s gonna happen.

I am now at a predominantly white institution as a vice president. We are having the same kinds of conversations. This is not peculiar for Peace Corps; this is a national dialogue, some systemic things we need to fix. The agency has to be braver than it has been.

Harris Bostic: I like to ask hyperbolic questions in situations like this: What if the goal of Peace Corps was to have 90 percent of Volunteers be people of color? What would be done differently? How would recruitment and benefits be explained? How would the application process be different? Reentry?

Take it further: What if, in 1961, when they were designing the Peace Corps, they were designing it for people of color and people from the lower socioeconomic 90 percent? How would the Peace Corps have been developed?

What if, in 1961, when they were designing the Peace Corps, they were designing it for people of color and people from the lower socioeconomic 90 percent? How would the Peace Corps have been developed?

Like I said, hyperbolic questions. But think about Peace Corps in 1960–61: Who did it appeal to? A young, white, usually female, from middle or upper class. It has grown from there.

To the structure over 60 years — how do we rebuild? We can’t forget that equality is different from equity. We don’t have to treat everyone the same. If people coming in are people of color, Black, lower socioeconomic levels — they should be given different benefits and opportunities, a different return. There’d be pushback. But ask those bold questions — if we really want to get high numbers of people of color in the Peace Corps — what we have to do, or what we have to stop doing.

This Coalition

Melvin Foote: This is just the tip of the iceberg. Before I joined Peace Corps out of Gunnison, Colorado, I had a column in a newspaper called “The Back of the Bus.” I wrote about the experience of Black people. My audience were cowboys, folks up in the mountains. A guy wrote me a note — white guy from Michigan — and we met over coffee. He told me that he went to Ghana as a Peace Corps Volunteer, fell in love with a Ghanaian woman, and what is my opinion about interracial marriage?“You love who you love. I can’t tell you about that. But, ”I said, “what is this Peace Corps?” I wanted to go to Africa. I put in my application.

A few months later, they wrote: You're going to Ethiopia. I thought: Ethiopia—the Middle East, because of the Bible stories. I went to the library, found an atlas — Ethiopia, right in the heart of Africa. When we flew over, I thought that Tarzan would be at the airport to take us to the village. That's the level of knowledge we had about Africa. I was shocked when I got to the airport and people were in suits and ties and carrying luggage and doing the things that people do at airports.

My message is: Don't agonize, organize. You could get mad all the time; here in Washington you’re always mad.

How far we have come — and how far we have to go. I’m an advocate. My message is: Don't agonize, organize. You could get mad all the time; here in Washington you’re always mad. Figure out what constructively you can do to shape policy.

I’ve had my hand on just about every U.S. policy toward Africa — everything from PEPFAR to the Rwanda intervention to President Obama’s Young African Leaders Initiative. We have to find constructive ways to add our voices, educate people about the Peace Corps, raise the issue with members of Congress who ought to be more supportive of the Peace Corps. We’re a coalition of the willing who want to help continue the legacy of the Peace Corps.

WATCH MORE: The full conversation

This story appears in the Fall 2020 edition of WorldView magazine. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 - Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 - Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleLongtime Chicago Bears leader, his service in Peace Corps in Ethiopia changed how he saw the world. see more

Longtime Chicago Bears leader, his service in Peace Corps in Ethiopia changed how he saw the world.

By Jonathan Pearson and Steven Boyd Saum

Photo courtesy the Chicago Bears

Michael McCaskey was the grandson of the legendary George “Papa Bear” Halas and inherited the mantle of leading the Chicago Bears football team for nearly 30 years. He was president and CEO of the Bears 1983–89 and then chairman of the board 1999–2011. The team won their first (and so far only) Super Bowl in 1985. Peers voted McCaskey NFL Executive of the Year.He was born in 1943. He earned degrees in philosophy and psychology at Yale, and in 1965 he began two years as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ethiopia, teaching science and English in Fiche, a town on the edge of the Rift Valley.

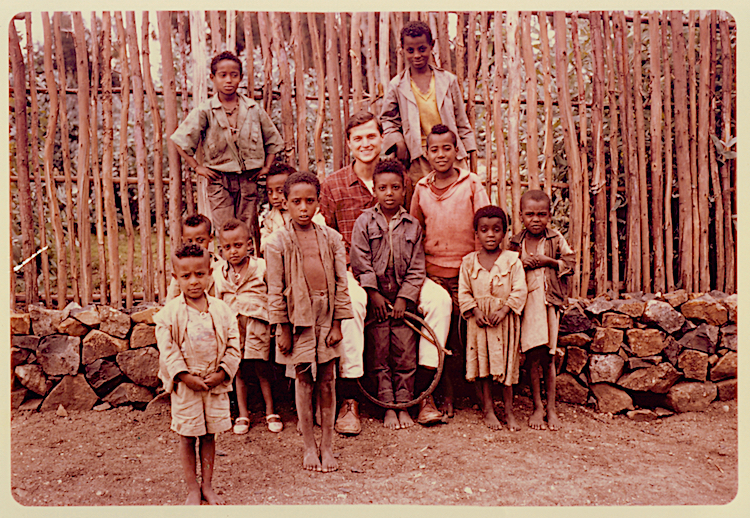

Fiche, 1965: Ethiopian students with teacher Michael McCaskey. Photo courtesy the Chicago Bears

“My students were astounding,” he said. “My days as a teacher in Ethiopia changed my perspective on the rest of the world, for which I am very grateful.”

He earned a Ph.D. in business from Case Western Reserve in 1972 and taught at UCLA and Harvard Business School. And yet, wrote fellow Ethiopia RPCV John Coyne, he “never really left Ethiopia. He never forgot the people, his students or the country’s ancient greatness.”

“My students were astounding,” he said. “My days as a teacher in Ethiopia changed my perspective on the rest of the world, for which I am very grateful.”

While head of the Bears, McCaskey began supporting and advising the Ethiopian Community Association of Chicago. “In 1999, during the long-running war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, Mike returned to Africa with four other former Peace Corps volunteers,” Coyne wrote for the Chicago Tribune. “Their mission was to promote peace by talking to the leaders of both countries.” U.S. Rep. John Garamendi, a fellow RPCV, was part of the delegation; he recounted the moment when the foreign minister of Ethiopia welcomed his old Peace Corps teacher—Mike McCaskey. The mission did not end conflict, but when peace was signed in 2000, the RPCVs were invited for the signing ceremony in Algiers.

Returning to Ethiopia: Michael McCaskey, left, meets with medical staff. Photo courtesy John Coyne

In 2005, McCaskey co-founded the Bears’ charitable organization, which has given over $21 million to some 100 organizations in Chicagoland to support education, youth athletics, medicine, and health awareness. After McCaskey retired, he devoted time to greater work with Ethiopia: supporting health care, leadership training, and education. Fiche, the village where he taught, is now home to a university; he worked with it to develop a program combining technology and student-directed learning. He died on May 16.

“Although Mike is gone,” Coyne writes, “his work, now named The Fiche Project, continues.”

-

Amanda Silva posted an articleEvery dollar matched to reach greater impact in Eritrean refugee camps. see more

In the Horn of Africa, a worsening refugee crisis is finding relief from Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (RPCVs).

By providing refugees with water, health and power, and resettlement services, and raising awareness of their plight through the power of film, the Peace Corps community is helping Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia and elsewhere.

In partnership with National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), Water Charity is providing refugees with access to water, basic health services, and solar panels. Water Charity’s Averill Strasser (Bolivia 1966-68) and Beverly Rouse are confident that more desperately needed help is on the way following the recent announcement of a pledged $25,000 match challenge from an anonymous donor. Join NPCA's fundraising campaign for these water and sanitation projects.

Linked forever to Eritreans following his service in the country from 1966 to 1968, John Stauffer is the co-founder and President of the America Team for Displaced Eritreans, providing resettlement services to many of the 400,000 Eritrean refugees who have fled their homeland.

Stauffer will speak about his experiences and how the Peace Corps community can help at Peace Corps Connect following the screening of Refugee: The Eritrean Exodus, director Chris Cotter’s raw, harrowing story of following the Eritrean exodus. The screening will kick off Peace Corps Connect on Wednesday, September 21—the International Day for Peace. Tickets are on sale through September 12.

Long considered the North Korea of Africa, Eritrea has caused one of the largest, yet lesser-known refugee crisis in the world through gross human rights violations. Refugees are largely confined to camps in Ethiopia, and many attempt a treacherous and often deadly trek to resettlement in Western Europe.

Following several successful projects in Ethiopia with currently-serving Peace Corps Volunteers and after viewing Refugee, Water Charity’s Strasser decided it was time to help in the camps. The NPCA-Water Charity partnership is well underway, and the $25,000 match challenge will add to progress already being made.

Ethiopian and Eritrean RPCVs have been actively involved in their host countries for many years, especially since war broke out between the two nations in the late 1990s. For their efforts to broker a peaceful resolution to a border dispute in 1999, the Ethiopian and Eritrean RPCV group was awarded NPCA’s Loret Miller Ruppe Award.

You can donate to NPCA-Water Charity projects in Ethiopia here, and join us at the screening of Refugee to become part of the conversation led by John Stauffer at Peace Corps Connect.