Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleMapping and reinventing cultures. Radical responsibility. Counting tiles and waiting in line. see more

Mapping and reinventing cultures. Radical responsibility. Counting tiles and waiting in line. That long lunch may be your ticket. And other insights from a conversation with business thinker Erin Meyer.

In Erin Meyer’s first book, there’s a point where she assumes the persona of a Danish designer exasperated at how much time she’s having to spend socializing with would-be manufacturing partners in Nigeria: “Can’t we just get down to business and sign a contract?” The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business answers that by mapping cultural expectations around the world when it comes to leading or communicating, persuading or disagreeing, giving feedback or setting an agenda.

Meyer served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Botswana 1993–95 and is a professor at INSEAD in Paris, one of the world’s leading business schools. Published in 2014, her book quickly caught the attention of business thinkers and leaders around the world. One of them: fellow Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and Netflix founder Reed Hastings. That led to Meyer’s second book, co-authored with Hastings and published in 2020, No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention.

She spoke with WorldView editor Steven Boyd Saum. Excerpts.

BEGINNING: TEACHING AND LEARNING

I always wanted to be in the Peace Corps. My parents were psychologists, really interested in other parts of the world; we often traveled to kind of remote areas. I served in Botswana, and I taught English in a rural school. There was no electricity, no running water. When I look back, it’s clear my whole career started in Botswana. Teaching junior high school classes of 40 and 50 kids, I had to learn how to be engaging in front of a group. I’m often a keynote speaker; everything I learned started with trying to figure out how to get these kids’ attention.

I had a copy of What Color Is Your Parachute? and I would come home from teaching and spend hours working through the activities. I determined I was going to be a cross-cultural consultant and teacher. Then, back in Minnesota, for a couple years I ran the English Learning Center, a program for Hmong and Somali immigrants and refugees. Most were illiterate; they needed to learn how to read and write and speak in English. It was a natural step from what I had been doing in the Peace Corps, where I had learned so much about curriculum development.

BOOK 2: NO RULES RULES

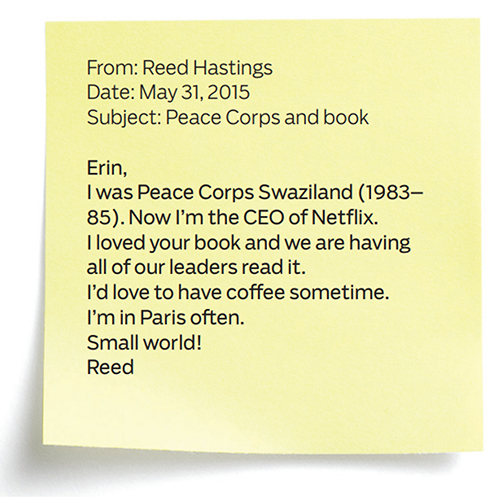

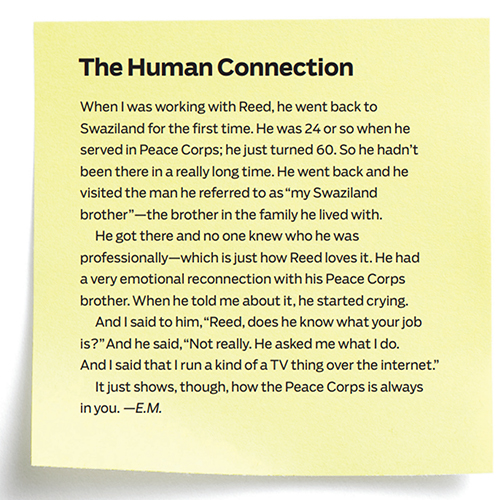

There is no way that I would have written that book with Reed if not for the Peace Corps. He seemed to trust me more because of the Peace Corps experience. He reached out to me as a Peace Corps Volunteer, not as the CEO from Netflix. That was the second point. The first point was, I was in the Peace Corps in Swaziland, just around the corner from where you were.

We spent dozens of hours together preparing the book. I always felt we had that grounding. Swaziland, now Eswatini, is the same tribe as Botswana; the languages are very similar. The words that he knew are really similar to words I knew in Setswana.

Photo by Brett Simison

TILES AND BUSES

Reed doesn’t generally think in stories, and I really needed a story from him to start the chapter on Netflix going global. I kept asking, and it was like peeling an onion. Finally he said, “Here’s a story you might like.”

When I moved to rural Swaziland in 1983 as a Peace Corps Volunteer, it was not my first international experience, but it was the one that taught me the most. It took only a few weeks for me to recognize that I understood and approached life very differently from the people around me.

One example came in my first month of teaching math to 16-year-old high school students. The kids in my class had been selected because of their strong mathematical abilities, and I was preparing them for upcoming public exams. On a weekly quiz I provided a problem that, from my understanding of their skill set, they should have been able to answer:

A room measures 2 meters by 3 meters. How many 50-centimeter tiles does it take to cover the floor?

Not one of my students gave the accurate response and most of them left the question blank.

The next day in class I put the question on the blackboard and asked for a volunteer to solve it. Students shuffled their feet and looked out the window. I felt my face becoming flushed with frustration. “No one? No one is able to answer?” I asked incredulously. Feeling deflated, I sat down at my desk and waited for a response. That’s when Thabo, a tall, earnest student, raised his hand from the back of the class. “Yes, Thabo, please tell us how to solve this problem,” I said, jumping up hopefully. But instead of answering the question, Thabo asked, “Mr. Hastings, sir, please, what is a tile?”

My students lived mostly in traditional round huts, and their floors were either made of mud or concrete. They couldn’t answer the question because they didn’t know what a tile was. They just couldn’t fathom what they were being asked to assess.

In Botswana we had combis, vans that run on prescribed routes. People would wait and the combi would come. The first time I went to get on one, the combi pulled up and I thought, Okay, I was here third, I’m going to get into the combi third. But everybody just muscled their way in. It didn’t take me long to realize, Erin, you better just muscle on like everybody else.

I have a chapter in The Culture Map about waiting in lines. That’s not the way I was taught in Minnesota — but you know, it works.

TRUST ME

In The Culture Map, my trusting scale looks at two different kinds of trust. There’s cognitive trust, from your brain: You’re on time, you do good work, you’re reliable, I trust you. Then there’s affective trust, from your heart: I feel this emotional bond, this personal connection with you. Because of that, I trust you.

In a country like the U.S., we have a strong emphasis on cognitive trust in a business environment and affective trust for home. In most every emerging market country in the world, affective trust plays a much larger role in a work environment. There’s a concrete reason: If institutions are not reliable yet, and legal systems are not reliable, it makes it very difficult to do business with strangers. In the U.S., we can easily do business with people we don’t know, because the legal system supports us. You can buy my product; we’ll sign a contract, and if you don’t pay, I’ll sue you. The legal system will allow that to work.

But if we’re in many countries where Peace Corps Volunteers serve, the legal systems may not be so reliable. We have to find ways to use our relationships to get things done.

When I think back, when I was teaching in Botswana, I had a very transactional relationship with the headmaster, whereas many of the local teachers had these father-child relationships. He was the paternal figure. I felt, I try to do a good job, get my students learning as much as possible, and that’s it. I never had a trusting relationship with him. As an older person, I’d go back and do it differently the next time.

Of course, in today’s world things have become more complicated with COVID. It’s hard to build emotional bonds when we can’t meet face to face. I’m always telling my clients that they have to invest in their Zoom calls — get to know each other personally.

LUNCH IS YOUR TICKET

For U.S. Americans, trust is all about: We sit down, figure out how we’re going to work together — how can I help you and how can you help me, and how can this project work out? We want a friendly relationship, but mostly we want to invest time in getting that project done well. If you’re trying to do business in Colombia and you take that route, you’re not going to get anything done. I worked with a U.S. team trying to do a merger in Colombia; they went to Colombia for a meeting, and in the morning they got down to business. Then it gets to be lunchtime and they go out to lunch. An hour, and the Americans are looking at their watches. An hour and a half, two and a half hours — that’s making the Americans really nervous. I know Peace Corps Volunteers have had that experience: How am I going to get anything done with all of this wasted time? When I was 23 years old or so, I felt, This is my first opportunity to really make a difference. I wanted to come in, get stuff done: set up the school newspaper and the art room, get my kids learning. I didn’t take the time to invest in relationships with the people that I was working with — that ultimately would have led to more success.

When you’re working in relationship-oriented societies, if you don’t take the time to really develop emotional bonds, you’re not going to get anything done. That’s the first part of the work: investing the time.

That said, I work a lot with Silicon Valley companies. All meetings are 30 minutes long. Here in France, we don’t have 30-minute meetings; their meetings here are 60 minutes — except for Netflix, Google, and Facebook.

FREEDOM, TALENT, AND RESPONSIBILITY

At INSEAD where I teach about cultural differences, my colleagues were always saying, “Why don’t you study corporate culture?” I thought it sounded so boring. Then I came across the Netflix culture deck, which has been downloaded over 20 million times. When I read it, I thought, That’s not boring. It was so honest. But there were things that I was just really taken aback by. First is: “Adequate performance gets a generous severance.” In business, a buzz phrase everywhere is “psychological safety.” But here’s the most innovative company of our time saying if you don’t perform at the super top level, you’ll get a generous severance. Then there’s: “Our vacation policy is take some”; “Our expense policy is act in Netflix’s best interest.” Those things didn’t bother me; I just couldn’t figure out how they could work in real life.

But when I started doing interviews at Netflix, people never led with those things. What they always lead with is: “I have been given so much freedom to do bold things and make decisions.”

When I started doing interviews at Netflix, people never led with those things. What they always lead with is: “I have been given so much freedom to do bold things and make decisions.”

At Netflix, people are given an enormous amount of freedom to do these huge things that no other company would let them do at their level — like sign off on a multimillion-dollar deal that you believe in. That really resonated with me. How great, I thought: a corporation where you can freely do big things, even at pretty junior levels.

Then I started to understand the other stuff, like adequate performance gets a generous severance. That was the foundation.

I have never thought about it this way before, but this is what happens in the Peace Corps. I didn’t have much teacher training, but I was able to use my creativity and my brain to make an impact. If we want to make a further correlation, that system works if you do a really good job getting good Volunteers. But if you don’t, and you send them out and give them huge amounts of freedom — well, Volunteers don’t get lots of money — but perhaps it’s not going to be money well invested. Until now, I’ve never thought about it like that: Peace Corps is just like Netflix!

WE ALL COME FROM SOMEWHERE

In my work, it used to be that people were resistant to talking about cultural differences. People would say, “But we’re all just humans, right?” We are. But we also all come from somewhere.

If you started bringing up culture, people might have responded, “I don’t want to stereotype. Let’s just talk about individuals.” That sounds great, but it’s really flawed. If we don’t talk about differences and what we believe it means to give feedback constructively, or what it means to contribute effectively in a meeting, we’re always observing behaviors from our own cultural lens.

If you started bringing up culture, people might have responded, “I don’t want to stereotype. Let’s just talk about individuals.” That sounds great, but it’s really flawed.

I’ve found lately that the conversation has shifted. When I start talking about cultures, people say, “You’re talking about national cultures. What about the subcultures in the countries?” Now there’s more a focus on: “I come from a different type of family, a different kind of culture in the U.S. than you do. And I would appreciate it if you understood me, and what I have to bring to the table based on the fact that I have a diverse background, and not that I am like you.”

I have really enjoyed that shift to a greater awareness, thinking about all of the positives that can come from diversity, and starting to shake ourselves a bit more to say: We can all bring something to the table, and we can seek to put ourselves in one another’s shoes and understand the roots of behaviors, the way we view one another. And we can seek to have a better, more inclusive approach that leads us to adapt our behaviors to improve our effectiveness.

That’s my life goal. And I do think that’s foundational work the Peace Corps is doing, too.

Returned Peace Corps Volunteers and co-authors: Erin Meyer and Reed Hastings. Photo by Austin Hargrave

-

Communications Intern posted an articleBefore Milana Baish served as a Volunteer, she interviewed 15 who had served across the decades. see more

Before Milana Baish served as a Peace Corps Volunteer, she interviewed 15 who had served across the decades. Then came the global evacuation.

Interview by Jordana Comiter

Meeting multiple returned Volunteers while studying at University of Texas, Austin, led Milana Baish to interview 15 RPCVs and write an honors thesis on how they perceived their experiences’ impact — in their communities and on themselves. They served from the 1960s to 2015, from Ghana to Sri Lanka, Brazil to Ukraine.

Then it was Baish’s turn. Her service in Zambia was cut short by evacuation. A Coverdell Fellowship brought her to Clark University for a program in development economics and international development.

Why did you decide to serve?

A lot of it had to do with the people I talked to. I wanted to learn about another culture. My time teaching in the Peace Corps solidified the path that I want to follow, working on education and equity in the U.S. and abroad. Most meaningful were relationships with fellow teachers and my host sister, learning from other women in the community, and learning from my students.

Teaching was hard. My classes were really large, up to 80 students. We were meant to work with another teacher, but my school was short staffed. We held teacher meetings to choose difficult topics and create a lesson plan together. Then someone would put on this class, and we’d all observe. With my English teaching, it was just me. I started an English club also; students could do extra material or homework. If they were trying to learn a phrase, I would make sure I knew how to say it in Bemba.

Embrace: Silvia Mwape, left, with Volunteer Milana Baish. Seated: Abigail Shamz. They hosted Milana as mother and sister. Photo courtesy Milana Baish

Talk about the evacuation — and who and what you left behind.

My group had gone for literacy training in the capital. There staff told us, “We’re evacuating you guys. You don’t have time to go back to your village, say goodbye, or pack. We’re flying you out from the capital.”

It was very sudden and still feels like an open chapter. I talk to people in my community, checking in. But I’m only able to keep in contact with people with smartphones. I can sometimes give messages to students through the teachers.

I was the first Volunteer at my site. Seven months is not a lot of time. There were a lot of things the community wanted to get done. We started a women’s group that did income-generating activities, as well as adult literacy classes. We were about to start our big project — beekeeping. I have heard from the local carpenter, who built structures for the nests; he is helping the women continue the project. We wanted to build a kitchen at the school as part of a meal program for students who go through 15-hour school days hungry. We talked about writing the grant but never got started.

What do you think it means to serve now versus then?

One thing we learn in Peace Corps training is, “You’re not going to be happy if you’re comparing yourself to the other Volunteers.” Everyone has different communities and schools they’re working in.

I went in knowing what other Volunteers had done but tried to have no expectations. The goals of the Peace Corps are the same. The world seems so large, but it’s really so small. It’s been an important part of the Peace Corps to just show us that we’re all in this together.

Teacher training: Students with Milana Baish. Photo courtesy Milana Baish

Talk about concern over neocolonialism and white saviorism.

That’s an important conversation being had now. I’m half Hispanic, but I’m very white passing. Going to Zambia, I’m just seen as a white woman. That was something I thought a lot about, because of the history of colonialism.

A couple times in my community someone would say, “You’re gonna bring all these great things to our community.” I would say, “We’re going to do this together. I want to know what you guys want to do.” I was there to help support, learn, and share.

A lot of Volunteers I spoke to for my research reflected on how their race might have affected things. Some were people of color who were treated differently by their communities. In Guatemala, one was the first Black person many had met.

It’s critical to have diversity in the Peace Corps, because that’s how the United States is.

Would you do it again?

Yes, 100 percent. Without a doubt.

International Women's Day, 2020: “We had a parade around the village and then celebrated with dancing and cooking at the school,” writes Milana Baish. Photo by Milana Baish

Jordana Comiter studies political science and communications at Tulane University. She serves as an intern with WorldView.

-

Megan Patrick posted an articleTravel with the Peace Corps community! see more

Blog post | Alan Ruiz Terol

There is little to say about the overwhelming and breathtaking beauty of India that hasn’t already been said. The Mexican writer and ambassador Octavio Paz wrote the following about his experience in the country: “Dizziness, horror, stupor, astonishment, joy, enthusiasm, nausea, inescapable attraction. What had attracted me? It was difficult to say: Humankind cannot bear much reality. Yes, the excess of reality had become an unreality, but that unreality had turned suddenly into a balcony from which I peered into—what? Into that which is beyond and still has no name…”

India will be the first Next Step Travel destination in 2017. The trip, February 16 to March 3, will explore the northern part of the country, such as Kolkata, New Delhi, Varanasi and Mumbai.

Next Step Travel is an initiative by the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA) to bring together the Peace Corps community for new experiences abroad. The program is unique in that it provides the opportunity to discover (or rediscover) a country with other supporters of the Peace Corps. Moreover, each itinerary incorporates Peace Corps values, such as unparalleled local access, cultural immersion, and time to explore remote areas off the beaten path.

People who have previously joined Next Step Travel trips strongly recommend the program to others. “What I like best about this experience is that it’s a safe way to travel that takes unfair advantage of no one,” says Carolyn C., an RPCV in Honduras who traveled to Guatemala. “It benefits everyone involved and the chosen adventures can be found nowhere else.”

The itinerary in India includes the must-sees of any trip to the country, such as the Taj Mahal — but don’t let the crowds of tourists scare you. The perfect beauty and outstanding monumentality of the building is worth the time. After all, the revered Indian artist and Nobel prize laureate Rabindranath Tagore described it as a “teardrop in the cheek of eternity”.

Travelers will see the sunrise illuminating the snow of Mt. Kanchenjunga from Tiger Hill, an ideal way to experience the immensity of the Himalayas. They will also observe cremation and bathing rituals in the Ganges at dawn, one of the most sacred sites for the Hindus.

The route will also offer original and unique ways to experience even the most mainstream spots. One excursion includes a tour of the back alleys of New Delhi by a young individual who was once living and surviving on the streets, providing insight into the daily lives of homeless children. Travelers will also attend a back-country trip in Rajasthan to experience rural life on the edge of the desert.

The India program is open to anyone, not only Returned Peace Corps Volunteers. In fact, Next Step Travel trips are the perfect opportunity for someone who couldn’t spend two years serving overseas to get a taste of the Peace Corps experience in just two weeks. To learn more about the trip to India and other Next Step Travel programs, click here. (The final registration deadline is November 18, 2016.)