Activity

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleVolunteers Serving in Times of Need see more

In 2021 Peace Corps Response marks a quarter century since its founding. Some moments that have defined it.

Photo: Community members in a village near Zomba, Malawi, learn to sew reusable sanitary pads for girls. Sheila Matsuda captured the moment as a Response Volunteer in Malawi 2018–19.

Crisis Corps was launched in 1996. At the outset, Volunteers were deployed to respond to natural disasters and assist with relief in the aftermath of violence. Over the years, the program expanded in scope, and Volunteers are now sent to meet a variety of targeted needs in communities around the world. In 2007, the name of the program changed to Peace Corps Response to reflect this shift.

Here’s a little history — including the program’s origins.

1992 | Beginnings

NAMIBIA: Peace Corps approves first short-term assignments. Ten Volunteers already serving elsewhere transfer to Namibia, responding to a prolonged, devastating drought.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

1994 | April

RWANDA: The president is assassinated, and a campaign of genocide unfolds. Returned Volunteers work with National Peace Corps Association to activate the NPCA Emergency Response Network and deploy RPCVs to support work with refugees. Peace Corps, in conjunction with the International Rescue Committee, also transfers five Volunteers to the Burigi refugee camp, where they serve for five months.

1995 | September

LESSER ANTILLES bears the brunt of Hurricane Luis. More than 3,000 people are left homeless. Eight RPCVS re-enroll with the Peace Corps, travel to Antigua, and help rebuild homes and provide training on hurricane-resistant construction.

Photo: NASA

1996 | June 19

CRISIS CORPS is officially launched at a Rose Garden ceremony with President Bill Clinton and Peace Corps Director Mark Gearan. The Peace Corps is “based on a simple yet powerful idea: That none of us alone will ever be as strong as we can all be if we’ll all work together,” Clinton says.

Photo: Peace Corps

1996 | December

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB: Peace Corps Director Gearan announces plans for a “reserve” of up to 100 Crisis Corps Volunteers; some to travel to Guinea and Ivory Coast to work with Liberian refugees.

1997 | July

CENTRAL EUROPE hit by devastating floods. RPCVs who served in the Czech Republic return with Crisis Corps to assist relief efforts.

Photo: Bohumil Blahuš

1998 | September

CARIBBEAN countries blasted by Hurricane Georges; more than 300 killed. Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Volunteers in Dominican Republic help with home reconstruction and emergency water and sanitation projects.

Photo: Debbie Larson / National Weather Service

1998 | October

CENTRAL AMERICA slammed by Hurricane Mitch. Hundreds of RPCVs who served in the region contact the agency to serve; Volunteers already in the region assist, too. Relief efforts in Honduras, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Crisis Corps Volunteers have also served in Chile, following an earthquake, and in Paraguay in the wake of flooding.

2000 | June

HIV/AIDS CRISIS: Peace Corps Director Mark Schneider calls on RPCVs to consider devoting their time, skills, and experience to serve in Crisis Corps as part of a new HIV/AIDS initiative. Five African countries have requested Volunteers in this capacity.

Photo Credit: Peace Corps

2001 | April

BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA: Crisis Corps Volunteers begin assignments in first country where Peace Corps had no prior presence. They assist local municipalities and NGOs, plus international aid organizations.

2002 | January

MAURITANIA hit by torrential rains, causing severe flooding. Red Crescent of Mauritania requests Crisis Corps assistance to help homeless families.

Image: Jon Harald Søby

2002 | February

AFGHANISTAN: After the swearing-in of new Peace Corps Director Gaddi H. Vasquez, President George W. Bush announces that a Peace Corps team will travel to Afghanistan to assess how the program could help with reconstruction. It is possible a Crisis Corps team could follow. But Volunteers do not return to Afghanistan.

Photo: Alejandro Chicheri / World Food Programme

2002 | July

MICRONESIA struck by Typhoon Chataan, most devastating natural disaster in the country’s history. On the island of Chuuk, Crisis Corps Volunteers assist with reforestation and soil stabilization, and begin work with communities on water sanitation facilities.

Photo: Federated States of Micronesia Department of Foreign Affairs

2002 | November

MALAWI hosts its first Crisis Corps Volunteers, requested by the government and UNICEF to address cholera outbreaks and assist with prevention.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2004 | March

GHANA: Crisis Corps Volunteers help launch HIV/AIDS education initiative.

2004 | November

ZAMBIA: Volunteers funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) work with neighborhood health committees and ministry of health.

2004 | December

INDIAN OCEAN: A 9.1 magnitude earthquake generates a tsunami, devastating communities in a number of nations. Scores of RPCVs serve with Crisis Corps in Thailand and Sri Lanka to assist with relief measures.

Map: Wikimedia Commons

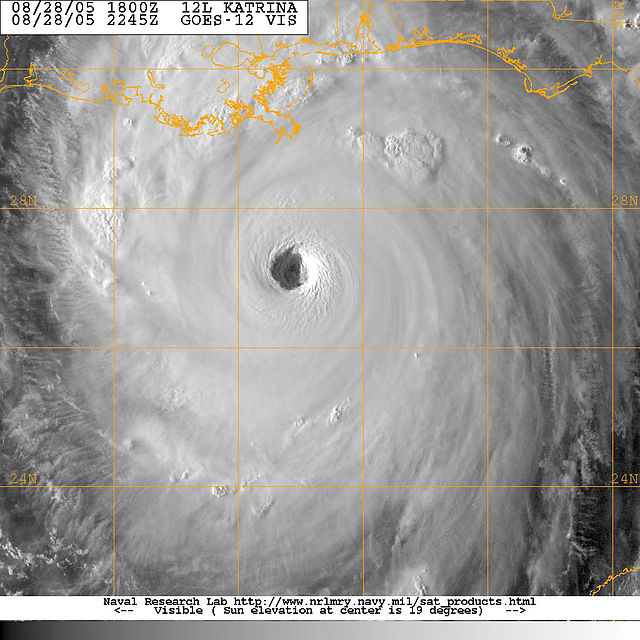

2005 | August

U.S. GULF COAST, particularly the New Orleans area, bears the brunt of Hurricane Katrina. For the first time, Crisis Corps Volunteers are asked to serve domestically; they partner with FEMA on relief work in hurricane-ravaged areas. While Peace Corps is an international organization, Director Gaddi Vasquez notes, “Today, as many of our fellow Americans are suffering tremendous hardship right here at home, we believe it is imperative to respond.” Volunteers take on 30-day assignments. Projects range from opening a disaster recovery center in the Lower 9th Ward to distributing food and water to displaced families. In total, 272 Volunteers serve 9,323 days and contribute 74,584 hours of service.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2005 | October

CENTRAL AMERICA hit by Hurricane Stan. In Guatemala, Crisis Corps Volunteers assist with reconstruction.

Photo: NASA

2007 | October

TULANE UNIVERSITY: Crisis Corps International Scholars Program launched; it pairs work on a master’s degree with a Crisis Corps assignment.

2007 | November

PEACE CORPS RESPONSE is the new name for Crisis Corps. Peace Corps Director Ron Tschetter says the new name better captures what Volunteers do, addressing critical needs in health, education, and technology — along with serving in disaster situations.

Photo: Peace Corps

2008 | October

LIBERIA: Response Volunteers lead the return of the Peace Corps, after an absence of nearly two decades. They work in education to revitalize training, schools, libraries, and more; and in health training. Their swearing-in ceremony is attended by Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, Peace Corps Director Ron Tschetter, and U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield.

Photo: Peace Corps

2010 | January

HAITI struck by 7.0 magnitude earthquake and scores of aftershocks. Some 250,000 people die;

1.5 million are left homeless, without access to clean water or food. Many hospitals are destroyed. Response Volunteers serve as part of global relief efforts.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

2012 | January

JAMAICA: Dorothy Burrill, 73, is first Response Volunteer who hasn’t already served in the Peace Corps. Eligibility now open to those with 10 years’ work experience and language skills.

2012 | March

GLOBAL HEALTH SERVICE PARTNERSHIP launched in collaboration with PEPFAR and Global Health Service Corps. The goal: address shortages of health professionals by investing in capacity building and support for existing medical and nursing education programs in African nations of Tanzania, Malawi, and Uganda.

2012 | October

SOUTH AFRICA: Response Volunteer Meisha Robinson and 12 Peace Corps South Africa Volunteers collaborate with Special Olympics staff and community members to organize the inaugural Special Olympics Africa Unity Cup. Fifteen nations’ soccer teams compete.

Photo: Special Olympics

2013 | November

THE PHILIPPINES pummeled by Super Typhoon Yolanda, killing thousands. Response Volunteers assist in affected areas.

2014 | September

COMOROS: Peace Corps announces it is returning, after a decade’s absence, with 10 Response Volunteers leading the way — to teach English and support environmental protection.

Photo: Peace Corps

2015 | March to April

MICRONESIA hammered by Typhoon Maysak. Response Volunteers assist with reconstruction.

2015 | December

PARTNERSHIPS: Peace Corps Response and IBM Corporate Service team up to engage highly skilled professionals to work collaboratively. Response also leverages partnerships with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Rotary International.

2019

ADVANCING HEALTH PROFESSIONALS program launched in five countries: Eswatini, Liberia, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. The program succeeds the Global Health Service Partnership and assigns Volunteers to nonclinical, specialized assignments that enhance the quality of healthcare in resource-limited areas, improving healthcare education and strengthening health systems at a societal level.

Photo: Peace Corps

2020 | March

GLOBAL: COVID-19 leads Peace Corps to evacuate all Volunteers and Response Volunteers from around the world.

2021 | May

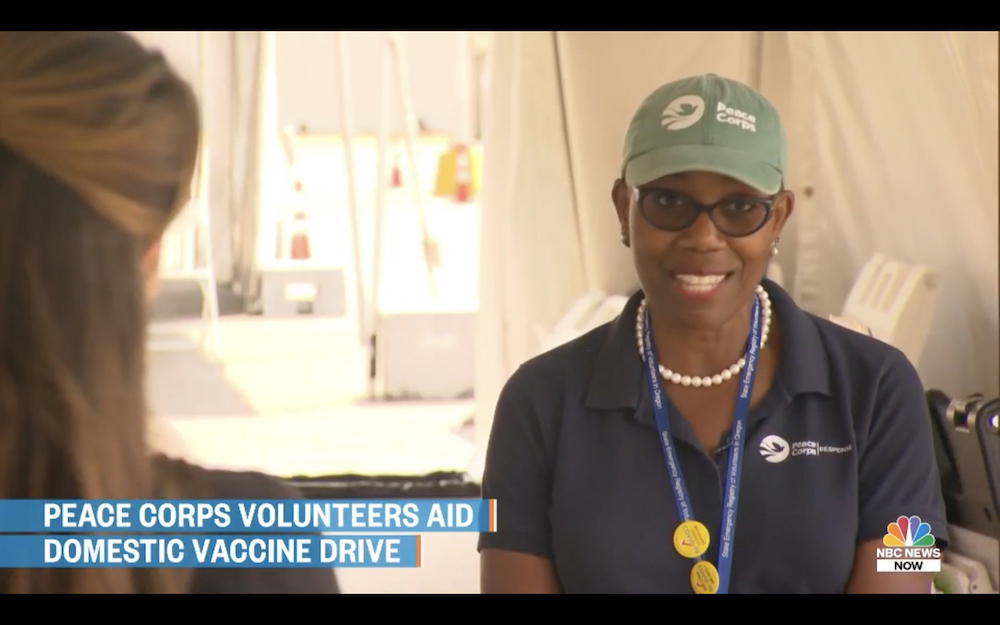

UNITED STATES: Response Volunteers begin serving with FEMA community vaccination centers to battle the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Photo: Peace Corps

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWithin 48 hours she was on a plane, headed to serve in Katrina relief efforts. see more

Priscilla Goldfarb

Peace Corps Volunteer in Uganda (1965–67) | Crisis Corps Volunteer in Alabama, United States (2005)

By Joshua Berman

From the Winter 2010 edition of WorldView

Photo: Priscilla Goldfarb serving as a Crisis Corps Volunteer with FEMA after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Courtesy Priscilla Goldfarb

Priscilla Goldfarb, a longtime nonprofit executive and former National Peace Corps Association board member, had a 40-year gap between her Peace Corps service in Uganda in the mid-1960s and her first Response assignment. Two weeks after Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc across the Gulf Coast — and not long after she retired — Goldfarb received an email looking for volunteers. For years she had wanted to serve with Crisis Corps, but she had never been able to get away from her job and family. She responded immediately.

Katrina at 6 p.m. on August 28, 2005. Satellite image provided by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey

“After a flurry of paperwork exchanges and telephone interviews,” she says, “I found myself in about 48 hours headed to Orlando, Florida, for training.”

This was an exceptional turnaround; at the time, acceptance, medical clearance, and placement typically took around three months.

Goldfarb received an intensive 72-hour training from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, then was handed a FEMA hat and T-shirt and sent into the field. She was assigned with a buddy to a small town about an hour north of Mobile, Alabama, close to the Mississippi border. They were part of USA-1, the first-ever domestic deployment of Crisis Corps. More than 270 fellow Volunteers joined in the Katrina relief effort, also making it the largest deployment of Crisis Corps Volunteers.

For the first part of her assignment, Goldfarb worked 12-hour days, seven days a week. “It was intense, stressful, and exhausting,” she says. She helped people apply for FEMA assistance, teaching them how to fill out documents and fulfill requirements, and advising people of their rights. Of the 100-plus people Goldfarb served, none had exactly the same issues.

“Some were so traumatized, they wanted simply to talk about their situation and be listened to — and would leave without even filing an application.”

“Some were so traumatized, they wanted simply to talk about their situation and be listened to — and would leave without even filing an application,” she says. “Some had specific and urgent housing and clothing needs. Others needed reimbursement for chainsaws or generators.”

Flexibility and adaptability were part of the assignment. That also jibed with an agency assessment that recommended Peace Corps Response function as “an ‘engine of innovation’ by serving as the Peace Corps’ tool for piloting new programs to expand the agency’s presence and technical depth and to increase overseas service opportunities for talented Americans.”

What about the relevance of her Peace Corps service? “Alabama was about as far away as Uganda had been to this Northern-born and -bred woman,” says Goldfarb. “But there were many similarities to my Peace Corps assignment — the rural lifestyle, agrarian economy, and hidden poverty.” People would greet outsiders with a “mix of reserve, even suspicion, and at the same time, hospitality far beyond one’s means on the part of the people we were there to serve … Familiar, too, was the incredible strength, grace, and dignity of people on a daily basis facing the most adverse of circumstances.”

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

Joshua Berman is a writer and educator based in Colorado. He served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nicaragua 1998–2000. Follow his work at joshuaberman.net.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleWorking with women in Bosnia in the aftermath of the civil war — and during 9/11/2001 see more

Teresa Bonner

Peace Corps Volunteer in Lithuania (1996–98) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2001)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Mostar, years after the war. Teresa Bonner arrived there to serve as a Crisis Corps Volunteer in September 2001.

When I became a Peace Corps Volunteer in Lithuania, I expected to go help people. I had a background in design and marketing, and the country was transforming after the breakup of the Soviet Union. But the strongest lessons I came back with were understanding another culture — and that people are the same everywhere in the world: They want to be happy, take care of their family, have fun.

I was assigned to Junior Achievement of Lithuania; I helped with marketing, strategy, and publication of their main textbook. I also had individual clients and advertising agencies. And I helped translate materials with the Missing Persons Family Support Center; women would answer job ads in Germany and never return, probably because they were brought into sex trafficking.

In August 2001, I was recruited into Peace Corps Response Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Bosnian War had been over for six years, but they were still struggling. The organization I was working with helped women adjust to the trauma and loss of war. They were tough women with amazing senses of humor and approaches to life. They had made it through one of the worst civil wars in modern history; all had lost family members, yet they were strong.

“They were tough women with amazing senses of humor and approaches to life,” Teresa Bonner says of her coworkers in Bosnia. “They had made it through one of the worst civil wars in modern history; all had lost family members, yet they were strong.” Photo by Teresa Bonner

I arrived at my site on September 9, 2001. I remember going for a walk the morning of September 11, looking around the city that had been devastated by war. Most buildings were riddled with bullet holes. As I walked by a man fixing his door, I started crying. I truly realized how terrible war is.

When I got back to my apartment, my landlady yelled “Teresa!” She pointed to the TV — the twin towers were coming down.

“I would run in zigzag,” she said, “because you never knew if a sniper would want to shoot you.” She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t looking for sympathy. She was just telling me. So after 9/11, she said, “Now you know what it’s like to have a sniper. You never know.”

I had to skip work for a week. But I knew that I was surrounded by people who had gone through something even more traumatic. A woman I worked with would talk about how, when she was making her way to high school, “I would run in zigzag,” she said, “because you never knew if a sniper would want to shoot you.” She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t looking for sympathy. She was just telling me. So after 9/11, she said, “Now you know what it’s like to have a sniper. You never know.”

I was in a predominantly Muslim community. Part of me wondered, Do they hate me? But it wasn’t like that at all. There was also this, I learned from people in Bosnia: The United States is a superpower, but if this can happen to America, who’s safe? I had some powerful conversations with the women I worked with about that.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleOne of those moments I thought, We’re doing something right. see more

Lily Asrat

Peace Corps Volunteer in Namibia (1996–98) | Crisis Corps Volunteer in Guinea (2000) | Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Eastern Caribbean–St. Lucia (2006)

As told to Ellery Pollard

Photo: Reviewing HIV records in St. Lucia: Lily Asrat working at the National AIDS Program Secretariat. Courtesy Lily Asrat

I’m Ethiopian American, and my parents exposed me to a lot of travel early on; they essentially raised me to be a global citizen. I understood that there’s so much out there in the world, and that there isn’t just one way of being. I saw Peace Corps as a continuation of this trajectory that started from childhood.

For my first Peace Corps service, I went to Namibia, which had just achieved freedom from South African colonial rule and the apartheid system. It was like coming to the United States immediately following desegregation: a lot of post-conflict tensions, a society coming to terms with racial healing, and people trying to coexist in a new landscape. It was a difficult time because there were still vestiges of armed struggle. But it was also a hopeful time because the majority of the population — who had been brutalized and subjugated — were feeling and seeing hope, freedom, and access to information and education.

I was a teacher trainer on a collaboration with USAID. The country was moving away from an education system based on apartheid — separate and unequal. The new Ministry of Education charted a path to develop new curricula that would be accessible to the whole population of Namibia.

While I was training teachers, my community was faced with a growing HIV epidemic. There was no treatment or testing accessible. There was a lot of stigma; it was considered a disease of gay men in the Western world, so people didn’t speak about it. But there were people sick and dying — a lot of teachers whose funerals I attended. My host sister died from HIV. It was devastating. That was the impetus for me to go down the track of public health. I realized that the real threat to the education system — and to the majority of the young, viable, productive populations of the country — was HIV. I got involved in doing HIV prevention work and education, collecting teaching aids and materials that I could share within the community.

Over a decade later, I found myself once again in Namibia working for another organization and witnessed significant improvements in access to treatment. At one clinic there was an HIV-positive woman seeing her doctor; she gave me her baby to hold. The baby was HIV negative. They had the knowledge and treatment available to provide the mother with antiretroviral therapy so she could avoid transmitting HIV to the baby during birth and breastfeeding. It was one of those moments in my life when I thought, We’re doing something right.

They had the knowledge and treatment available to provide the mother with antiretroviral therapy so she could avoid transmitting HIV to the baby during birth and breastfeeding. It was one of those moments in my life when I thought, We’re doing something right.

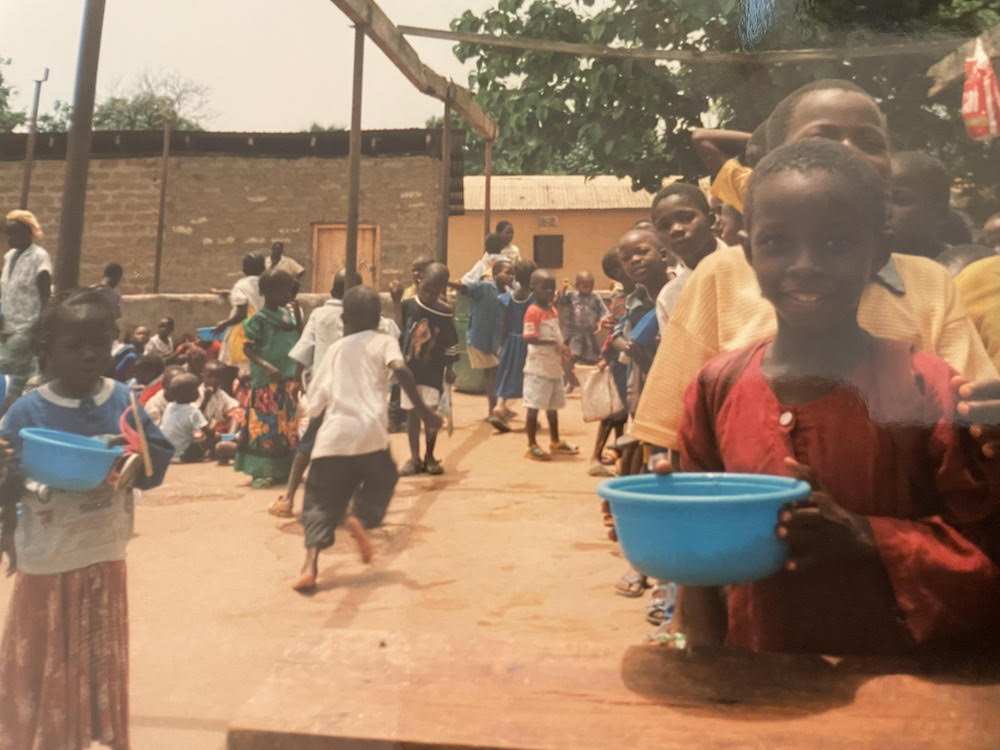

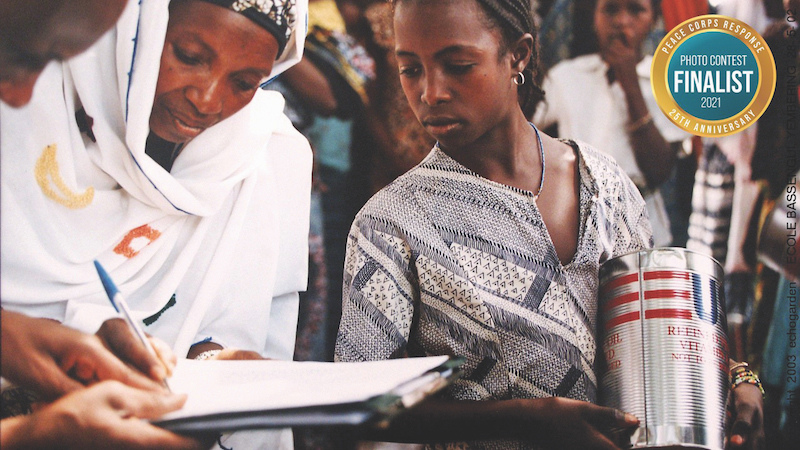

In 2000, I went to Guinea as a Crisis Corps Volunteer seconded to the International Rescue Committee, which was responsible for providing housing, nutrition, education, and psychosocial support for Liberian and Sierra Leonean refugees. Speaking French was one key criteria; the other was being a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer — able to hit the ground running. Being professional and flexible, able to develop relationships and trust in communities where you’re working — and do anything required with minimal support within hardship areas.

Child refugees in Guinea, where Lily Asrat worked as a Crisis Corps Volunteer seconded to the International Rescue Committee, responsible for providing housing, nutrition, education, and psychosocial support. Photo by Lily Asrat

We had an entire stock of food intended for refugee kids that was stolen overnight. It was clearly an inside job; the people responsible for guarding it had disappeared. Those moments are heartbreaking — but not so uncommon. I sought out immediate solutions, using our resources to help navigate that crisis. While the theft of food intended for refugee children was difficult, we also had many examples of wonderful community engagement such as the groups of women who volunteered on a daily basis to cook, distribute, and clean up. They put time, effort, and love into preparing meals for those kids. They made the hardships worth the effort.

By the time I served as a Response Volunteer in Eastern Caribbean (St. Lucia), I had worked at the CDC for three years, had two more master’s degrees, and I’d been in my doctoral program at U.C. Berkeley, studying public health; it was an opportunity to apply my training and experiences, and give back in a different way. I was placed at the National AIDS Program Secretariat to support strategy and guidance, monitoring and evaluation, and planning and grant writing. I have been very lucky in my career to have worked for three government agencies, several multilaterals, and prestigious academic institutions, but nothing has been as rewarding for me as my three stints as a Volunteer in Namibia, Guinea, and St. Lucia.

This is part of a series of stories from Crisis Corps and Peace Corps Response Volunteers and staff who have served in the past 25 years.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleShort-term, high-impact. Now marking 25 years since its founding. see more

Short-term, high-impact. Now marking 25 years since its founding.

By Steven Boyd Saum

Photo by Christian Farnsworth

A quarter century ago, at a midsummer White House Rose Garden ceremony attended by President Bill Clinton and Sargent Shriver, first director of the Peace Corps, a new type of Peace Corps service was announced to the world: Crisis Corps. Short-term, high-impact, it was, as then-Peace Corps Director Mark Gearan explained, “an effort to harness the enormous experience, skills, motivation, and talents that the Peace Corps, including its returned Volunteer ranks, possesses, and bring them to bear in an organized fashion during such crisis situations.”

At the outset, all Crisis Corps Volunteers were required to have already served in the Peace Corps. In fact, the program traces much of its origins to grassroots work by returned Volunteers. The National Peace Corps Association Emergency Response Network, activated to help in the aftermath of the Rwanda genocide in 1994, provided powerful inspiration.

IN ITS FIRST YEARS, Crisis Corps enlisted hundreds of Volunteers to serve in places from Bosnia to Guinea to El Salvador. Volunteers worked with communities recovering from conflicts, hurricanes, earthquakes, and more. Following the devastating tsunami that hit Thailand and Sri Lanka, among other countries, in 2004, the largest cohort ever of Crisis Corps Volunteers deployed there. Months later, hundreds more began serving Gulf Coast communities battered by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita — the first time Volunteers served in the United States.

Flooding in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Photo courtesy Wikimedia

By 2007 the broadening nature of assignments led the agency to rename the program Peace Corps Response. Assignments last three months to one year, shorter than a standard 27-month term of Peace Corps service. That makes them more feasible for working professionals, who have to take a leave of absence. And, since 2012, Response Volunteers have included individuals who haven’t previously served in the Peace Corps.

Mothers and daughters pick up gifts of cooking oil as an incentive for school attendance, part of a World Food Programme effort in Guinea documented by Christian Farnsworth, who served as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer.

It’s interesting to note that in 2020 the Commission on Military, National, and Public Service issued a report that called for exploring virtual service assignments for Peace Corps Response, to further open up opportunities for people able and willing to serve but not, perhaps, able to travel to other countries. Indeed, after the evacuation of all Peace Corps Volunteers in March 2020, the Peace Corps agency launched the Virtual Service Pilot — which connected evacuated Volunteers and Response Volunteers with organizations and communities in countries where they had been serving.

In May 2021, more than 150 Peace Corps Response Volunteers deployed domestically, as part of a partnership with FEMA. “By sending specialized volunteers to targeted assignments, we are helping to advance Peace Corps’ mission of world peace and friendship,” Peace Corps Response Director Sarah Dietch noted. Response Volunteers began serving with community vaccination centers to reach underserved communities — an effort that seems more important with each passing day, as another wave of COVID-19 takes a terrible toll.

Grandmother in a Ukrainian village, photographed by Michael Andrews as part of the Baba Yelka project.

In the 25 years since Peace Corps Response began, more than 3,800 Volunteers have served in over 80 countries — and twice in the United States. As we go to press, Response is recruiting for 136 openings, with Volunteers departing “no earlier than late 2021” for Belize and Guyana, undertaking assignments that include literacy specialist, adolescent health specialist, and epidemiology specialist. They’re recruiting for positions departing “no earlier than early 2022” for more than 20 countries, from Mexico to Malawi, Uganda to Ukraine, Georgia to Guatemala, Jamaica to South Africa.

Kudu released into Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve in Malawi, where Betsy Holtz worked as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer

Response Volunteers were at the vanguard as Peace Corps returned to countries such as Liberia. Civil war forced the program there to close in 1990. In 2007, when Response Volunteers arrived to serve, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, president of Liberia, personally attended the swearing-in ceremony.

In the pages that follow, we bring you a brief history of the program. Along with milestones, take note of the stories of lives and communities that have been shaped by the experience. It’s no coincidence that there’s a recurring theme of building together, whether that’s infrastructure or shared knowledge, and undergirding it all, that commitment to nurturing peace and friendship.

Three girls in Comarca Emberá-Wounaan, eastern Panamá; Eli Wittum documented environmental work in the country, and when he visited this region these three were delighted to pose for a photo.

Steven Boyd Saum is the editor of WorldView.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleA few Returned Peace Corps Volunteers tried to stem the tide of suffering. see more

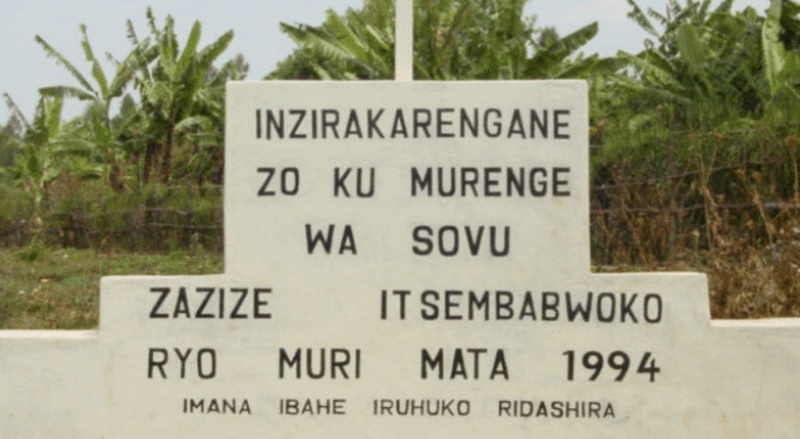

A catastrophic humanitarian crisis in 1994 led to the death of millions of Rwandans. A few Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who tried to stem the tide of suffering proved a powerful catalyst for Crisis Corps, a global endeavor launched by the Peace Corps agency two years later.

DIGITAL EXCLUSIVE: An excerpt from a story in the Winter 2013 edition of WorldView magazine.

By David Arnold

Carol Pott and John Berry were married shortly before John started a U.S. Agency for International Development small enterprise development project in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, a small, poor, heavily populated but relatively peaceful Central African country that John’s boss told Carol was “Africa for beginners.”

Seven months later, in April 1994, when John left for a conference in a neighboring city, the plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down over Kigali.

The crash ignited events that gave Rwanda’s reputation new meaning for Carol, and the world. “I heard the plane crash while I was eating dinner with my neighbor,” Carol recalls. “It shook the ground. Soon after, mortars began flying over the house.”

“I heard the plane crash while I was eating dinner with my neighbor. It shook the ground. Soon after, mortars began flying over the house.”

A mortar shell struck the back of Carol’s house. She hid some neighbors in her ceiling. Later that night, militia broke into the neighbors’ house and hacked to death the guard and gardener. “The militias were killing children in the streets.”

When John heard about the violence he was directing a conference in a southern Rwanda convent. He quickly paid final wages to some staff, then death benefits to the widows of others who were early casualties. He asked two nuns at the convent, Sister Gertrude Mukangano and Sister Maria Kisito Mukabutera, to look out for the remaining staff and left.

Traumatized by their experience, Carol and John were evacuated from Rwanda and saw the full scope of what they had escaped as they watched on U.S. television some of the more than 10,000 Rwandan bodies floating down the Kagera River, washing ashore in Uganda or onto the islands of Lake Victoria. The total of Rwandan dead is still not known, and is believed to be 500,000 to a million.

Planning began in a San Rafael bar

“We were back in San Rafael, California, watching the genocide on TV, feeling depressed,” says John, when they also saw a local news reporter interview Steven Smith, a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer in Zaire, a neighboring Central African country where many of Rwanda’s refugees had fled. Smith was recruiting Returned Peace Corps Volunteers to help in Rwanda, so John — a Niger RPCV — called.

“We wanted to return to Rwanda and do something that was positive,” Carol says. Carol had not served in Peace Corps but she was deeply moved by her time in Rwanda conducting economic surveys and volunteering for a Kigali human rights group.

Smith called then-President of the National Peace Corps Association Chic Dambach and they set in motion grassroots initiatives that became known as the RPCV Rwanda Project, a project that almost 20 years later many experts in post-conflict peace-building believe had a profound impact on post-conflict Rwanda and continues to constructively influence other crises.

Photographed a decade after the genocide at the Sovu convent in Southern Rwanda, a mass grave memorial stands for the hundreds of genocide victims who were killed at the convent, including half of John Berry’s project staff. Berry raised funding for the memorial, and the sisters of the convent organized its construction. A rough translation: “To the victims from the village of Sovu who were killed in the genocide in April 1994. May God bless their eternal rest.“ Photo by John Berry

What they did in Rwanda

Chic Dambach found funding through USAID for Smith to build the NPCA’s Emergency Response Network (ERN), a pre-internet telephone tree that gathered the names, contacts, and resumes of hundreds of RPCVs willing to turn their cross-cultural experiences, language, and skill sets to the Rwanda crisis. The ERN became a popular recruiting source for NGOs and U.N. agencies for years to come.

Mark Gearan, who was then director of the Peace Corps, understood the long-term implications of ERN and asked permission to borrow the concept when he created the federal agency’s own Crisis Corps, later renamed Peace Corps Response.

Carol flew to Washington to work in the NPCA office on a training curriculum for the U.N. High Commission for Human Rights and U.N. human rights field monitors. Many were fresh law school graduates and most had no knowledge of the country, the issues, or Rwanda’s indigenous languages, yet they were supposed to find Rwandans needing protection and identify evidence such as mass graves to preserve for later prosecutions.

Carol sifted through Peace Corps training manuals and Where There Is No Doctor, and interviewed such experts as a forensic anthropologist, the head of Physicians for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch specialists on Somalia, and the director of the Congressional Hunger Center to write the curriculum she and John could provide for the first Geneva training. Later, Steve and Carol returned to Rwanda to evaluate the work of the monitors.

READ MORE: The rest of David Arnold’s story in the Winter 2013 edition, available on the WorldView app.

David Arnold was editor of WorldView magazine in 2013 and, for his decades at the helm of this magazine, now holds the title of editor emeritus.

-

Orrin Luc posted an articleThe second time in history that Peace Corps Volunteers have been deployed in the United States. see more

Beginnings. Good sense. And the second time in history that Peace Corps Volunteers have been deployed in the United States.

By Steven Boyd Saum

Photo from 1994: A Rwandan refugee camp in eastern Zaire. Photo courtesy CDC

Here’s an instructive but heart-wrenching place to start, if we want to tell the big story at the center of this edition of WorldView. It’s one of crisis and response: April 1994. A plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi is shot down over Kigali. The assassination ignites events that lead to horrific genocide in Rwanda. Over 100 days, 800,000 people are killed. More than 2 million flee to neighboring countries as refugees; another 1.5 million are internally displaced.

Returned Peace Corps Volunteer John Berry and his then-wife, Carol, were in Rwanda at the time. Carol was working with a human rights group; John was directing training efforts for micro-enterprise development. They were evacuated as the nightmare began to unfold.

Back in California, John and Carol were watching news reports on the genocide when they saw a local reporter interview another returned Volunteer, Steven Smith, who was in Zaire — where many Rwandan refugees had fled. Smith was recruiting returned Volunteers to help Rwanda. John called him. And Smith reached out to National Peace Corps Association President Chic Dambach. As WorldView editor emeritus David Arnold wrote in this magazine, “They set in motion grassroots initiatives that became known as the RPCV Rwanda Project.” They also found funding to build NPCA’s Emergency Response Network — “names, contacts, and résumés of hundreds of RPCVs willing to turn their cross-cultural experiences, language, and skill sets to the Rwanda crisis.”

And they brought together returned Volunteers to work with refugees on the ground.

NOT LONG AFTER, in 1995, Mark Gearan was sworn in as Peace Corps director. He took a page from the Emergency Response Network playbook and launched Crisis Corps, a new Peace Corps program to harness the skills and cross-cultural experience and care returned Volunteers might bring to crisis situations. The program was formally inaugurated in June 1996 at a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden. Among those present for the occasion: Sargent Shriver, the first director of the Peace Corps, and his wife, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, as well as longtime Peace Corps champion Senator Harris Wofford.

“The real gift of the Peace Corps is the gift of the human heart, pulsing with the spirit of civic responsibility that is the core of America’s character. It is forever an antidote to cynicism, a living challenge to intolerance, an enduring promise that the future can be better and that people can live richer lives if we have the faith and strength and compassion and good sense to work together.”

At that ceremony, President Bill Clinton observed a truth we know well. “The dedicated service of Peace Corps Volunteers does not end when their two-year tour is over,” he said. “So let us always remember that the truest measure of the Peace Corps’ greatness has been more than its impact on development. The real gift of the Peace Corps is the gift of the human heart, pulsing with the spirit of civic responsibility that is the core of America’s character. It is forever an antidote to cynicism, a living challenge to intolerance, an enduring promise that the future can be better and that people can live richer lives if we have the faith and strength and compassion and good sense to work together.”

AND WHAT OF THAT — compassion and good sense and working together? In 2021, for the second time in history, Peace Corps Response Volunteers have been deployed domestically. The first time was in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. When Response Volunteers were recruited this past spring, there were more people offering to serve than there were slots available. It seemed that the pandemic was winding down. Just a few months back — but a long time ago. More recently, when one group of Response Volunteers was working with vaccination outreach efforts in underserved communities in Oregon, the sense of this is about over couldn’t have been further from reality. As a reporter for NBC News who had spent time with the Volunteers observed, ICUs in the state were virtually at capacity.

Peace Corps Response Volunteer Judith Jones talks with NBC News reporter Maura Barrett. Jones was evacuated from Belize in March 2020 and in 2021 has been part of the second domestic deployment of Peace Corps Volunteers.

So, in service around the country amid this pandemic, we find one answer to another question we ask in this edition: What does it mean to serve now? A question that bears asking as Peace Corps Response marks its 25-year anniversary and the Peace Corps celebrates 60 years. And a question that, for this edition, we put to Mark Gearan in his recent capacity as one of the leaders for the congressionally mandated National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Over several years, that bipartisan commission endeavored, for the first time in the nation’s history, to gain a comprehensive view of what it means to serve — and what the needs and as of yet untapped opportunities are. They sought to answer, in concrete terms: How can we get to 1 million Americans serving every year?

Sixty years ago, the Peace Corps took wing fueled by JFK’s exhortation “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” In helping to define and inspire service for a new generation, and in reaching a scale this country has never seen, the ideas and the ideals that have shaped Peace Corps have something to bring to the table. Read on.

DIGITAL EXCLUSIVE: David Arnold’s 2013 story on Rwanda and the NPCA Emergency Response Network.

Steven Boyd Saum is editor of WorldView and director of strategic communications for National Peace Corps Association. He served as a Volunteer in Ukraine 1994–96.

-

Steven Saum posted an articleEvacuated Volunteers will put their skills and experience to work at home in a time of crisis see more

Evacuated Volunteers will put their skills and experience to work at home helping during the pandemic.

By Glenn Blumhorst

This week we received very welcome and timely news: Peace Corps Response Volunteers will be deployed to work with FEMA, to assist at vaccination centers across the United States. Not since the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina have Response Volunteers been deployed domestically.From the early days of the pandemic, we’ve seen members of the Peace Corps community step up to help communities across the United States — as contact tracers, working with food banks, making masks, as part of NPCA’s Emergency Response Network in Washington State, and so much more.

For the past year we’ve supported national legislation that has tried to jump-start formal involvement of returned Volunteers throughout communities here at home. Now it’s happening.

For the past year we’ve supported national legislation that has tried to jump-start formal involvement of returned Volunteers throughout communities here at home. We made the case that Volunteers who were evacuated from around the world in March 2020 can and should be given opportunities to bring their skills and experience to serve at home. That’s exactly what is happening now. As the end of the pandemic is within sight, it’s heartening that Response Volunteers can help at this critical time.

Those eligible to serve as part of the partnership with FEMA include returned Volunteers evacuated from their overseas posts in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. As the release from the Peace Corps agency notes:

Volunteers will work at federally supported Community Vaccination Centers (CVCs) across the country. The agency will soon begin recruiting for this special domestic deployment. Assignments will focus on urgent needs as identified by FEMA, and on communities that have been traditionally underserved. Volunteers will be assigned to language support, administrative, logistical, and other work that supports vaccination centers’ operations. It is anticipated that Peace Corps Volunteers will be deployed into the field by mid-May.

Peace Corps Response, which was originally established as Crisis Corps 25 years ago with a signing ceremony in the Rose Garden, is well positioned to help address the COVID crisis domestically. And in a very timely initiative undertaken two years ago, Peace Corps Response launched the Advancing Health Professionals program, to improve health care education and strengthen health systems on a societal level in resource-limited areas. This is the kind of program that can help lead the way as Volunteers begin to return to the field internationally — to work with communities to address their immediate needs.

Resilience, commitment, and a sense of working in solidarity with communities defines the Peace Corps experience. We need that more than ever.

Read the full release from Peace Corps here.

Glenn Blumhorst is President and CEO of National Peace Corps Association.