A catastrophic humanitarian crisis in 1994 led to the death of millions of Rwandans. A few Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who tried to stem the tide of suffering proved a powerful catalyst for Crisis Corps, a global endeavor launched by the Peace Corps agency two years later.

DIGITAL EXCLUSIVE: An excerpt from a story in the Winter 2013 edition of WorldView magazine.

By David Arnold

Carol Pott and John Berry were married shortly before John started a U.S. Agency for International Development small enterprise development project in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, a small, poor, heavily populated but relatively peaceful Central African country that John’s boss told Carol was “Africa for beginners.”

Seven months later, in April 1994, when John left for a conference in a neighboring city, the plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down over Kigali.

The crash ignited events that gave Rwanda’s reputation new meaning for Carol, and the world. “I heard the plane crash while I was eating dinner with my neighbor,” Carol recalls. “It shook the ground. Soon after, mortars began flying over the house.”

“I heard the plane crash while I was eating dinner with my neighbor. It shook the ground. Soon after, mortars began flying over the house.”

A mortar shell struck the back of Carol’s house. She hid some neighbors in her ceiling. Later that night, militia broke into the neighbors’ house and hacked to death the guard and gardener. “The militias were killing children in the streets.”

When John heard about the violence he was directing a conference in a southern Rwanda convent. He quickly paid final wages to some staff, then death benefits to the widows of others who were early casualties. He asked two nuns at the convent, Sister Gertrude Mukangano and Sister Maria Kisito Mukabutera, to look out for the remaining staff and left.

Traumatized by their experience, Carol and John were evacuated from Rwanda and saw the full scope of what they had escaped as they watched on U.S. television some of the more than 10,000 Rwandan bodies floating down the Kagera River, washing ashore in Uganda or onto the islands of Lake Victoria. The total of Rwandan dead is still not known, and is believed to be 500,000 to a million.

Planning began in a San Rafael bar

“We were back in San Rafael, California, watching the genocide on TV, feeling depressed,” says John, when they also saw a local news reporter interview Steven Smith, a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer in Zaire, a neighboring Central African country where many of Rwanda’s refugees had fled. Smith was recruiting Returned Peace Corps Volunteers to help in Rwanda, so John — a Niger RPCV — called.

“We wanted to return to Rwanda and do something that was positive,” Carol says. Carol had not served in Peace Corps but she was deeply moved by her time in Rwanda conducting economic surveys and volunteering for a Kigali human rights group.

Smith called then-President of the National Peace Corps Association Chic Dambach and they set in motion grassroots initiatives that became known as the RPCV Rwanda Project, a project that almost 20 years later many experts in post-conflict peace-building believe had a profound impact on post-conflict Rwanda and continues to constructively influence other crises.

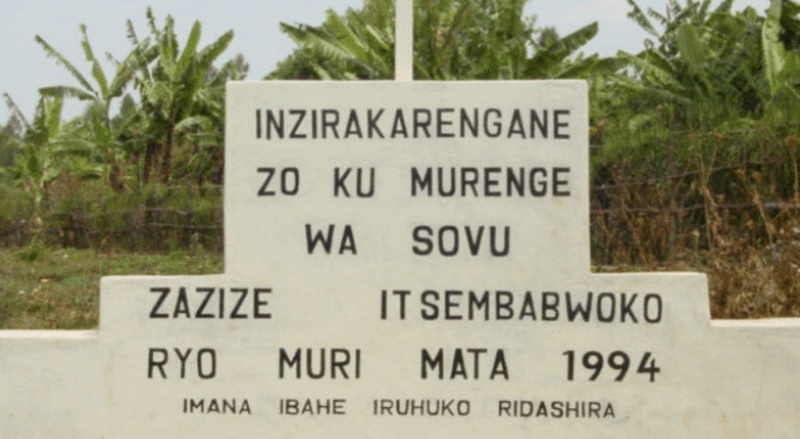

Photographed a decade after the genocide at the Sovu convent in Southern Rwanda, a mass grave memorial stands for the hundreds of genocide victims who were killed at the convent, including half of John Berry’s project staff. Berry raised funding for the memorial, and the sisters of the convent organized its construction. A rough translation: “To the victims from the village of Sovu who were killed in the genocide in April 1994. May God bless their eternal rest.“ Photo by John Berry

What they did in Rwanda

Chic Dambach found funding through USAID for Smith to build the NPCA’s Emergency Response Network (ERN), a pre-internet telephone tree that gathered the names, contacts, and resumes of hundreds of RPCVs willing to turn their cross-cultural experiences, language, and skill sets to the Rwanda crisis. The ERN became a popular recruiting source for NGOs and U.N. agencies for years to come.

Mark Gearan, who was then director of the Peace Corps, understood the long-term implications of ERN and asked permission to borrow the concept when he created the federal agency’s own Crisis Corps, later renamed Peace Corps Response.

Carol flew to Washington to work in the NPCA office on a training curriculum for the U.N. High Commission for Human Rights and U.N. human rights field monitors. Many were fresh law school graduates and most had no knowledge of the country, the issues, or Rwanda’s indigenous languages, yet they were supposed to find Rwandans needing protection and identify evidence such as mass graves to preserve for later prosecutions.

Carol sifted through Peace Corps training manuals and Where There Is No Doctor, and interviewed such experts as a forensic anthropologist, the head of Physicians for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch specialists on Somalia, and the director of the Congressional Hunger Center to write the curriculum she and John could provide for the first Geneva training. Later, Steve and Carol returned to Rwanda to evaluate the work of the monitors.

READ MORE: The rest of David Arnold’s story in the Winter 2013 edition, available on the WorldView app.

David Arnold was editor of WorldView magazine in 2013 and, for his decades at the helm of this magazine, now holds the title of editor emeritus.