Author: Jeremiah Johnson

For months now, I have been centrally involved in advocacy related to the unnecessary medical separation of newly diagnosed, HIV positive volunteers. Unfortunately, this is not my first time fighting this battle: back in 2008 I myself opted to take an HIV test as part of my midservice medical exam and found out I had the virus. Much to my surprise, I was told that I could not finish my service in any Peace Corps country; that I would need to be medically separated and then reapply. According to the Peace Corps, I would need to be dismissed with no guarantee of return because healthcare infrastructure did not exist in any country to manage my condition, my situation would not “resolve” in the standard 45 days allotted to any volunteer who has been medically evacuated, and that my HIV would render me incapable of completing my duties as a volunteer.

Fortunately for me, the ACLU successfully challenged the Peace Corps on my behalf, getting the administration to publicly recommit to upholding the Rehabilitation Act which stipulates that reasonable accommodations must be made for volunteers with healthcare challenges. We interpreted this as a decision by Peace Corps administration to stop dismissing HIV positive volunteers and instead meet the modest healthcare management needs of newly infected individuals as they continue to serve in country. For ten years, the issue seemed to be resolved; no new cases of unnecessary service interruption emerged, and I even heard about a handful of volunteers who were able to return to service because of my advocacy.

Yet earlier this year, I was contacted by two volunteers within a span of two months who found themselves being sent home after testing positive for HIV. This time the argument seemed to exclusively center around the Peace Corps’ inability to care for these volunteers in country, that their conditions were simply too unstable. Once again, I have been engaged in very public advocacy pressing the Peace Corps to make reasonable accommodations for volunteers living with HIV. At present, both volunteers remain back in the US, and I am resolved to continue my advocacy until they are back in service.

Both in 2008 and now, I’ve found that RPCVs and current volunteers tend to, at first glance, support the decision to medically separate newly diagnosed volunteers. Given the lack of education that most Americans have around HIV, that’s not necessarily surprising. Their conception of what it means to have the virus is informed by old narratives from the 80s and 90s, long before we had the modern treatment available to us now, long before we knew that that same treatment not only allows us to live a completely normal life span, but also ensures that we will not pass along the virus sexually.

What many people don’t understand is that these volunteers are 100% healthy. Also, overly inflated fears of in-country management of the condition are unfounded; HIV is extremely simple to manage in 2018, all we require is access to pills and routine blood work. So long as they remain on treatment, these recently dismissed volunteers will also remain completely healthy, with no complications from their HIV whatsoever. Ten years since my diagnosis, I have never experienced any sort of physical ailment due to the virus, and I remain healthier than most HIV negative people I know. There is also no particular urgency or instability involved with these volunteers’ situations that requires them to have their service interrupted. Yes, it is advisable to get them on to treatment right away, and rarely that might require taking a few different regimens to find the right one, but they are not in immediate danger of developing complications. Because all volunteers are tested for HIV prior to service, we know that these are new infections, and that, even in cases of rapid disease progression it takes years for HIV to progress to AIDS. The fact is that, if a new HIV infection is your only health concern, you’re most likely completely healthy physically and completely able to resume your service. Certainly, the shock and psychological impact of an HIV diagnosis must also be considered and addressed, and manifestations of serious mental health concerns, like any comorbidity, may change the situation. But we cannot make HIV a special case here; volunteers experience extreme stress all the time and manage to return to service. A great many people diagnosed with HIV are more than able to work through our new diagnosis in country. I know that for me, being sent home prematurely was almost certainly worse for my psychological wellbeing.

We also know that volunteers living with HIV are not a transmission risk, particularly when they are successfully on treatment. Many people may struggle to get past thinking of us as viral vectors, carriers of an infectious disease. Yet we know that HIV is only transmitted through a small subset of human activities– sex, sharing needles, breast feeding– and that the majority of people newly diagnosed with HIV make adjustments to ensure they will not pass the virus on. And if that isn’t reassuring enough for you, since 2011 we have seen a growing body of evidence showing that people who are successfully treated and reach what we call an “undetectable viral load” will not sexually transmit the virus to others, even if a condom breaks or is not used. The concept is called Undetectable=Untransmittable or U=U and you can read more about it at www.preventionaccess.org.

Newly diagnosed volunteers are healthy, with treatment we remain completely healthy, and we pose no threat to the communities in which we live and serve. What’s more, we are an invaluable commodity that should be specifically recruited and retained for service. Peace Corps is one of a handful of government bodies that directly receives funds from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a massive program initiated by George W. Bush in 2003 to address HIV abroad. As such, the Peace Corps is charged with addressing misinformation and stigma surrounding the virus; and who better to do that than those of us living with it?

Undoubtedly, negotiating volunteer healthcare is not easy. Peace Corps administration has a specifically challenging responsibility to manage the health and wellness needs of around 7000 volunteers at any given time, across many different settings. It is understandable that throughout its history it has taken a somewhat paternalistic stance toward managing volunteer care. But in the case of HIV, they have been needlessly losing valuable, healthy volunteers without reason.

I am hopeful, however, that this will be resolved in the near future. In a recent face to face meeting with new Peace Corps Director Jody Olsen, the administration agreed that their approach to HIV needs to be reevaluated in light of the objections that I and many other HIV/AIDS advocates have raised. And while it’s too early for me to declare victory, and I will not stop my advocacy until the two recently dismissed volunteers are returned to service, I am hopeful that we have a pathway forward to ensure that people living with HIV are valued, recruited, and retained going forward.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the National Peace Corps Association or its members.

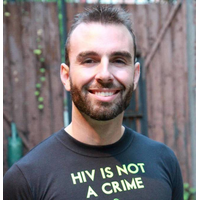

About the Author:

Jeremiah Johnson (Ukraine 2006-2008) is a fulltime HIV/AIDS activist living in Manhattan. Since 2013 he has worked at Treatment Action Group, first as their HIV Prevention Research and Policy Coordinator and currently as the Community Engagement Coordinator. He holds a master’s in public health from Columbia University and is a nationally recognized leader in advocacy for people living with and vulnerable to HIV.