When President John F. Kennedy signed the Peace Corps Act into law, it permanently established the Peace Corps as an independent agency. But forging the legislation and getting it through Congress didn’t happen on their own. We take a look at those beginnings and share some stories few have heard. And we look ahead to what the Peace Corps must become.

A conversation with Bill Josephson, Bill Moyers, Joe Kennedy III, and Marieme Foote

The legislation that established the Peace Corps on a permanent basis, the Peace Corps Act, was signed by President John F. Kennedy in an Oval Office ceremony at 9:45 a.m. on September 22, 1961. On the day JFK signed the act, three groups of Volunteers were already in their countries of service: Colombia, Ghana, and St. Lucia.

To mark the 60th anniversary of the signing, National Peace Corps Association hosted a conversation with two key figures in the establishment of the Peace Corps — and one Volunteer who was evacuated in 2020, and whose commitment to the ideas and ideals of the organization points to the Peace Corps of the future. The conversation was moderated by Joe Kennedy III — JFK’s great-nephew and himself a returned Volunteer who, while he served in Congress, championed the creation of the Peace Corps Commemorative, which will establish a place in the heart of the nation’s capital to symbolize what the Peace Corps represents.

Here are edited excerpts. You can also listen to the conversation on Spotify.

Bill Josephson

Bill Josephson

Co-architect of the Peace Corps and Founding Counsel for the agency

Photo by Rowland Scherman

Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers

Journalist and first Associate Director of the Peace Corps

Photo by Yoichi Okamoto / LBJ Library

Joe Kennedy III

Joe Kennedy III

Former Congressman and Peace Corps Volunteer in Dominican Republic 2004–06

Photo courtesy Joe Kennedy III

Marieme Foote

Marieme Foote

Peace Corps Volunteer in Benin 2018–20; Donald Payne Fellow at Georgetown University

Photo courtesy Marieme Foote

“The Towering Task”

Joe Kennedy III: Walk us through those early days — taking an idea, translating that into legislation, getting members of Congress around it.

Bill Josephson: My colleague Warren W. Wiggins said that we needed to make an impact with this administration. The Peace Corps was what everyone asked us for our opinion about. The result was the writing over Christmas and New Year’s of 1960–61 the memo “The Towering Task,” and the distribution of it to as many people as we could find who would read it, including Harris Wofford. Harris describes walking into Sargent Shriver’s office, carrying “The Towering Task” and saying to Sarge this is something he ought to read — only to find Sarge was already reading it.

Joe Kennedy III: There’s a story I’ve heard about getting the bill signed into law that involves you and a number of senators in a cloakroom, some chicken scratch on a piece of paper, a clerk to type something up, a couple of taxicabs … And lo and behold, the Peace Corps was born.

Bill Josephson: Roger Kuhn was principal draftsperson of the Peace Corps Act. I was an important kibitzer and the upfront person in House and Senate hearings. The bill went to the Hill without a lot of changes from the White House or the budget division, and was introduced by Hubert Humphrey in the Senate and the chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee, Doc Morgan of Pennsylvania. This was a genuine bipartisan effort. We enjoyed strong support from Republicans. Two women on the Foreign Affairs Committee, Marguerite Stitt Church of Illinois and Elizabeth Bolton of Ohio — strong, traditional Republicans — were amazingly persuasive supporters of the Peace Corps.

This was a genuine bipartisan effort … Two women on the Foreign Affairs Committee, Marguerite Stitt Church of Illinois and Elizabeth Bolton of Ohio — strong, traditional Republicans — were amazingly persuasive supporters of the Peace Corps.

Joe Kennedy III: Tell us how you were able to get such a big idea through Congress. At the moment, ideas are difficult to get through, to put it mildly.

Bill Moyers: There remains to this day, 60 years later, a certain vibrancy among people who were involved in the Peace Corps. It has really been a marvelous moment in American history. Lord knows so many people had talked about something like this from the beginning!

In 1950, Walter Reuther, head of the United Auto Workers, proposed a kind of tech corps of young people who would go abroad. Maurice Albertson, who had done pioneering work in mechanics and hydraulics, wrote a draft of a Point Four youth program. Hubert Humphrey introduced the first bill in 1957. He said he got no enthusiasm. Reverend James Robinson of Crossroads Africa founded that program with an eye that could have well been on a future Peace Corps. This was an American idea that rose among the ranks of people who did not hesitate to call themselves idealists but knew how to pass bills in Congress; that made a big difference.

Sarge gave me the job of associate director for public affairs. I had three portfolios: one, Congressional relations; two, public affairs — news, press, and advertising; and three, recruiting. When Bill Josephson and Warren Wiggins and those who helped them drafted the legislation, they sent Sarge and me up to the Hill to sell it. We had to persuade a Congress that contained many advocates for the Peace Corps — but also some real opponents.

We first called on a handful of friends: Hubert Humphrey and Congressman Henry Reuss from Wisconsin, who had proposed a Peace Corps along with Humphrey. We wanted our friends to stand and fight for us. As Sarge and I prowled Capitol Hill, we decided to call on every member of Congress. I think we made it, with the exception of one.

He was literally known as “Otto the Terrible” because he was so opposed to any foreign aid, except that which took a brickbat and tried to hit a communist over the head. He called the Peace Corps a “kiddie corps.”

We went to known adversaries of the Peace Corps — those who had declared opposition before they knew what it was. One was a congressman born in 1916, Otto Passman. He was literally known as “Otto the Terrible” because he was so opposed to any foreign aid, except that which took a brickbat and tried to hit a communist over the head. He called the Peace Corps a “kiddie corps.” He got Congressman H.R. Gross, an influential conservative from Iowa, on his side, and he called it a utopian playground.

I went first to see Otto Passman, because I was from the South. He was from a deeply Southern and segregationist district in Louisiana, not far from my hometown across the Texas border. I got my congressman, populist Wright Patman of East Texas, to call Otto the Terrible and say he was sending this kid over to see him and say, “Just listen to him.” I went over and Passman said, “What do you want to talk to me about?” I said, “I just am here to arrange a meeting with the future director of the Peace Corps.” “I don’t want to see any future director of the Peace Corps. I just want to veto the thing when it comes to my desk.” I said, “Don’t you want to sit down with the president’s brother-in-law and talk about this?” There was silence. He said, “The president’s brother-in-law?” I said, “Yes, Sargent Shriver, who is John Kennedy’s brother-in-law, married to Eunice, is going to head the Peace Corps, and he would like to come see you.”

That was an appeal to Otto the Terrible. He saw Shriver, and Shriver knew instantly what to talk about, because we had done our homework. While he didn’t want to hear about the Peace Corps, we wanted to talk to him about what it meant to be an entrepreneur. Sarge walked in and started talking to the Congressman about how he had started a business during the Depression selling refrigerators and other hotel and business equipment. Passman said, “How did you know that?” Sarge said, “I used to run the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, and we saw a lot of refrigerators and other things like that pass through. I was just wondering how you managed to do that in the Depression.”

Otto melted a little. He gave us a long visit that day. We probably paid more visits to Otto Passman, chairman of the influential Foreign Relations Funding Committee in the House, than any other Congressman. We never brought him around. But word spread quickly that Sarge had been given the courtesy of extended and frequent visits to Passman, and that turned into a lot of goodwill. When the legislation passed, we got some 90 Republican votes in the House; very few who had stood up and condemned it before they knew anything about it, protested. They didn’t vote for us, but they didn’t fight us tooth and nail. The legislation sailed through the Senate.

There was never a better salesman, never a better idealist at explaining what an ideal is, than Sargent Shriver.

There was never a better salesman, never a better idealist at explaining what an ideal is, than Sargent Shriver. He could adjust very quickly to the mood, interest, and concerns of a member of Congress. We sat down with the member of Congress, and their staff asked questions. By the time it was over, I don’t think there was a program in Washington that had a better aura around it. And we had the young, dynamic president behind us.

The moment: September 22, 1961, President John F. Kennedy (laughing) signs HR 7500, the Peace Corps Bill, in the Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C. Looking on (from left): Senator Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island (in back); Director of the Peace Corps, R. Sargent Shriver; Senator Philip A. Hart of Michigan (in back); Representative Edna Kelly of New York; Representative Chester Merrow of New Hampshire; Representative Thomas F. Johnson of Maryland (in back); Representative Clement Zablocki of Wisconsin; Representative Wayne L. Hays of Ohio (partially hidden behind Representative Zablocki); Representative Leslie C. Arends of Illinois (in back, facing right); Representative Roman C. Pucinski of Illinois; Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota; Representative Silvio O. Conte of Massachusetts (in back); Representative Thomas E. Morgan of Pennsylvania; Representative Cornelius E. Gallagher of New Jersey; Representative Sidney R. Yates of Illinois. Photo by Abbie Rowe / White House, courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

An important factor: We asked President Kennedy to ask Vice President Lyndon Johnson — for whom I had worked — to be chairman of the Peace Corps Advisory Committee. Johnson had been director of Franklin Roosevelt’s National Youth Program in Texas 1935–37. He had done the best job in the country of all the state directors. Johnson gave us the time we needed when the State Department and the Agency for International Development tried to take over the Peace Corps and turn it into just another box on the bureaucratic chart. Johnson explained patiently to Sarge and me how the bureaucracy worked. He had seen it for 30-some years. “Here’s what you have to watch out for. Here’s how you have to turn the corner without running into somebody.” Two and a half hours later, we knew what to do. We went and talked about preserving the independence of the Peace Corps, which Josephson and Wiggins had said was so essential. Every time we needed help on the Hill, the vice president came through.

During the campaign of 1960, I had served as the liaison between the traveling teams. For Johnson, my job was to coordinate logistics, prepare speeches, answer questions to keep us on track. Every day I was in touch with some member of the traveling Kennedy campaign — most often Kenny O’Donnell, his closest political advisor. When it came time for me to want to go to the Peace Corps after the election, both Kennedy and Johnson said no, because then who would interpret Austin to Boston? I persuaded Ken O’Donnell to persuade President Kennedy to let me go. It’s the best move of my life, and to this day I am deeply indebted to JFK and LBJ.

Bill Josephson: A little known fact: Bill Moyers is the drafter of the first public speech favoring the founding of the Peace Corps, even before the Michigan speech of Kennedy. Johnson gave a speech advocating the creation of the Peace Corps in Lincoln, Nebraska, two weeks before the Michigan moment. The speech was drafted by Bill Moyers. My wife is Nebraskan; she knows about that event.

When Lyndon Johnson read the speech that had been drafted for him he said, “I can’t deliver this stuff. It’s crap.” He said, “Write something stirring.”

Bill Moyers: There was a speech we had received by wire from headquarters in Washington. We were on the plane and had just taken off from Hampton, New York, headed for Lincoln, Nebraska. Johnson said, “I can’t deliver this stuff. It’s crap.” He said, “Write something stirring.” The proposal he made, based on that speech, was called a Youth Corps. I wish I’d used the phrase “Peace Corps,” but that hadn’t occurred to me. But it was a great event — and promptly lost to history.

“You wanted to be independent, you’re independent.”

Joe Kennedy III: I’ve often said there wasn’t a single day when I was serving in Congress that I didn’t draw on my experience as a Volunteer. It wasn’t so much the language skills, speaking Spanish; it was understanding that if you want to bring people together to achieve a common goal, they need to be active participants in that process, and you need to help create the circumstances to allow people to buy in and hear them out. You mentioned trying to keep the agency independent. That issue came up when I was serving in Congress, an effort to try to subsume the Peace Corps within the State Department.

Bill Josephson: One of the arguments was that the State Department and the to-be-transformed International Cooperation Administration — which would become USAID — regarded the Peace Corps as a gem, as opposed to what they did, which did not enjoy anything like broad support, either in Congress or in the nation. Foreign aid was — and to some extent, still is — the stepchild. They coveted the Peace Corps. Sarge and Warren and Bill and I felt that the Peace Corps, to succeed, had not to be any part of the foreign affairs bureaucracy or Cold War programs of the United States. Legislation was the vehicle for independence.

There was a climactic meeting in the White House. I was there. Also present was Ralph Dungan, an important member of the White House staff; and the director of the budget, David Bell. We waited to see the president but didn’t get in. Ralph purported to resolve the issue against the Peace Corps and in favor of the State Department and the foreign aid programs. Bill Moyers then went to the vice president. The vice president had a private meeting with President Kennedy later that day, and persuaded him — in the way that Lyndon Johnson uniquely could persuade people — to make the Peace Corps an independent agency. Ralph called me the next morning to tell me this decision. I said, “Well, I’d like to come over and smoke the pipe of peace with you. We’re going to be working together for a long time.” He said very clearly, “Uh uh. You wanted to be independent, you’re independent. Don’t come running to us when you’re in trouble!”

“Already more than 13,000 Americans have offered their services to the Peace Corps.” President John F. Kennedy delivers remarks after signing HR 7500, the Peace Corps Bill, in the Oval Office, White House, on September 22, 1961. Looking on (from left): Representative Edna Kelly of New York; Representative Clement Zablocki of Wisconsin; Senator Robert S. Kerr of Oklahoma (in back); Representative Roman C. Pucinski of Illinois; Representative Silvio O. Conte of Massachusetts (in back); Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota; Representative Thomas E. Morgan of Pennsylvania; Representative Cornelius E. Gallagher of New Jersey; Representative Sidney R. Yates of Illinois; Representative Harris B. McDowell of Delaware (in back, in shadow); Senator Clair Engle of California (partially hidden); Senator Albert Gore of Tennessee; unidentified man in back; Senator Jacob Javits of New York; Senator Thomas H. Kuchel of California; Representative John Brademas of Indiana; Senator John A. Carroll of Colorado; Senator John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky; Senator Paul H. Douglas of Illinois; Representative Carl Albert of Oklahoma. Photo by Abbie Rowe / White House, courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Bill Moyers: There is another point to be made — slightly less lofty: You can hardly channel the imagination up an organization chart, nor can the imagination flow downward through an organization chart. Along the way, there are other people charged with responsibilities and duties that cause them to hack away at that passion to reduce it to their grasp. To persuade Congress to support you, go up unencumbered by other people’s mistakes and less desirable thoughts. Make your case, and stand and fall on what you can say about what I, Sargent Shriver, am going to be responsible for — and if you don’t understand this, you can count on me to keep my word to Congress.

Those powerful barons in Congress who opposed the Peace Corps considered us naive, if not harebrained. You couldn’t have sent a 25-year veteran of the bureaucracy to give a tutorial. One morning I took Sarge to have coffee with the vice president. Johnson called me later and said: “The way to sell the Peace Corps is to sell Shriver. They won’t be able to resist him.” And they weren’t. Most were dazzled to be courted by the president’s charismatic brother-in-law, not some long-standing official from the bureaucracy.

I saw jaded politicians begin to pay attention as Sarge talked about America’s revolutionary ideas and our mission to carry them out in the world as down to earth, believable: card-carrying idealists who can show how freedom is served by a teacher in a classroom, clean water from a pump in the village square.

I’m not damning the bureaucracy. It is central to the running of our government. And what turned the tide was not Sarge’s glamour but his passion. I saw jaded politicians begin to pay attention as Sarge talked about America’s revolutionary ideas and our mission to carry them out in the world as down to earth, believable: card-carrying idealists who can show how freedom is served by a teacher in a classroom, clean water from a pump in the village square.

One old unreconstructed racist, whose chairmanship of a key subcommittee could have meant life or death for our appropriation, was aghast that young Americans living and working abroad under official auspices might not only practice miscegenation but bring it home with them. Only Shriver could answer that — not a schedule C appointee in the Agency for International Development. Because when that congressman made the case that if Volunteers went abroad, they’d come back and marry interracially, Sarge never blinked. He said, “Congressman, surely you can trust young Americans to do abroad exactly what they would do back in your district in Louisiana.” That left the man scratching his head. When I returned later, for a follow-up call, his secretary told me he had confessed, “I was had.”

You can’t get that from — bless their hearts — career people who’ve had so much drained from them by compromise over the years. It took this man making the case and saying, “Believe in me, because I believe in the Peace Corps.”

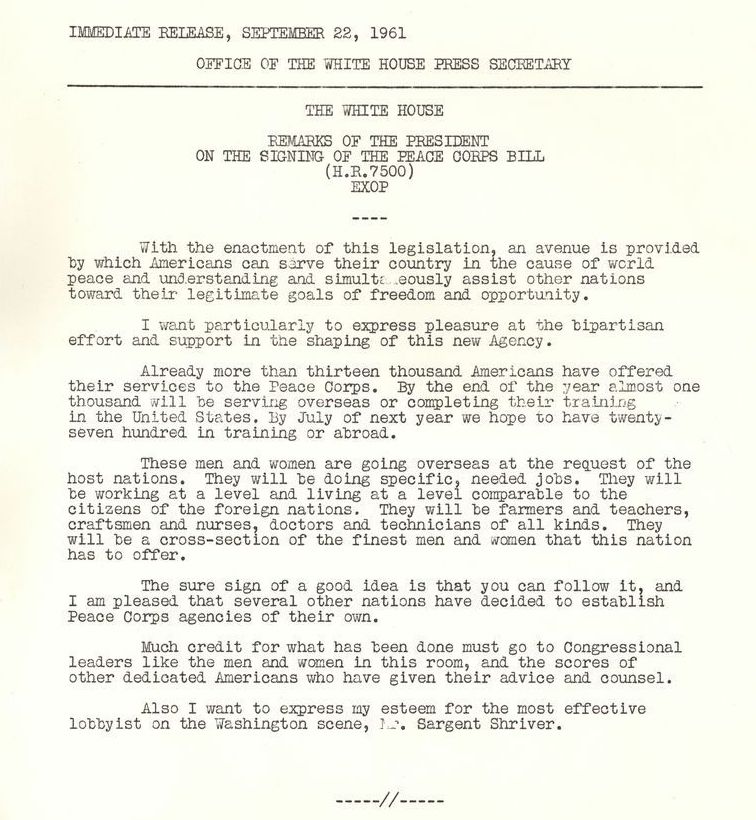

John F. Kennedy’s remarks on signing the Peace Corps Act. Courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

We carry two passports.

Joe Kennedy III: I’m struck not only by the power of the idea but the relentlessness and optimism its champions demonstrated. Given your experience in the Peace Corps’ conception, implementation, and development — and looking back over these 60 years — what does the Peace Corps mean to you?

Bill Josephson: The essence of the Peace Corps is service. That’s a concept we emphasized over and over. You could see it in the reaction of the University of Michigan students to President Kennedy’s off-the-cuff speech. You could see it in the flow of applications that followed the announcement of the Peace Corps. You can see it in what more than 250,000 Volunteers did in service, and continue to do in serving those ideals after their Peace Corps service.

Relieve misery, nurture minds, inspire others, crack open a little further the gates long shut by ignorance, bigotry, or just sheer misunderstanding.

Bill Moyers: What I take away is that America must always try to put its best foot forward. We will never know the prints it leaves — but we know that we still are trying as human beings to do our best in the world as patriots and as citizens of the world.

Sarge taught me that we carry two passports: one grounded in the soil of American democracy, which he served five years in the navy to defend; another as a global citizen. He believed that seeing a person could be as important as any institution — could relieve misery, could nurture minds, inspire others, and could crack open a little further the gates long shut by ignorance, bigotry, or just sheer misunderstanding. When I was his deputy, he gave me a copy of Chaim Potok’s The Promise and highlighted this paragraph: “Human beings don’t live forever, Reuven. We live less than the time it takes to blink an eye, if we measure our lives against eternity. So it may be asked what value there is to human life. There is so much pain in the world. What does it mean to suffer so much if our lives are nothing more than a blink of an eye? I learned a long time ago, Reuven, that a blink of an eye itself is nothing. The span of life is nothing; but the man or woman who lives that span, they are something. They can fill that tiny span with memory so that its quality is immeasurable.”

I believe almost every Peace Corps Volunteer has discovered that about him or herself. And what they did was immeasurable, and unforgettable.

All those years later, he just wanted to pass along that gratitude. He never asked my name, where I was from, what I was doing. He just wanted to take a moment to credit that individual.

Joe Kennedy III: When somebody asks me what Peace Corps service is all about, I often share the story of being on an overcrowded bus on my way back into Santo Domingo, in the Dominican Republic, when I got a tap on my shoulder. An older gentleman asked if I was a Peace Corps Volunteer. I was surprised and asked how he knew. He looked at me like I was crazy. Why else would I possibly be in the back of a crowded bus in the Dominican Republic? And he said, Thank you. Because when he was a little boy, there was another Volunteer sent to his village who put in a pipe to provide clean water to his community. He never got a chance, as a child, to be able to say thank you. All those years later, he just wanted to pass along that gratitude. He never asked my name, where I was from, what I was doing. He just wanted to take a moment to credit that individual. That matters.

New and enduring

Joe Kennedy III: We talked about the past and the roots of the Peace Corps. One of my mentors, Senator Chris Dodd, talked about the early days of the Peace Corps and getting dropped down in the Dominican Republic himself and picked up two years later. The world has changed now that everybody has a smartphone.

Marieme Foote: The Peace Corps was created on the heels of the civil rights movement. So much has changed in the past 60 years. My father, Mel Foote, served in Ethiopia in the 1970s. He had to drive to the village next door, hours away, to place a phone call at a post office to speak with his parents — maybe five times in his service. I had 4G in my village. I could stream Netflix. Look at the world around us — and conversations around racial justice, equity, class — and how this should affect the Peace Corps. These things are all connected. We have more Volunteers coming from diverse backgrounds, who are first generation, whose parents were served by Peace Corps Volunteers. My mother was served by Peace Corps Volunteers in Senegal. You see also a need for the Peace Corps itself to change; it can’t remain the same as it was in the ’60s. That’s a good thing. It was created as a radical, beautiful concept. National Peace Corps Association put out the report “Peace Corps Connect to the Future” last year, which brought out important issues that Volunteers today are facing, and ways we can support Volunteers and better serve communities. Those are questions we need to ask.

Look at the world around us — and conversations around racial justice, equity, class — and how this should affect the Peace Corps. These things are all connected.

Joe Kennedy III: In the early 2000s, I had to get on a bus to go into town to check email and such — but I was still in more or less consistent contact with my family; they could call a cellphone that worked. That constant flow of communication creates challenges, obviously. It also creates enormous opportunities when looking at climate change and the need to make changes and investments at the hyperlocal level. There’s an opportunity to leapfrog technologies and help make a dramatic impact, whether it’s climate resiliency, access to water, electricity, connectedness. There’s a huge opportunity for the Peace Corps as an organization to start to think: How do we leverage those opportunities that come with technology? How do we think through opportunities for partnerships — when obviously with COVID, we’ve seen that impacts around global health are hugely consequential? How can we leverage people on the ground in these communities, with the backing of the people of the United States, to make a long-term, sustained impact?

Marieme Foote: In my village, a lot of people didn’t have access to electricity; solar panels and renewable energy changed that. Among Volunteers I know, everyone has WhatsApp; they’re able to continue conversations overseas from the U.S., and a lot are working on projects with their communities and raising funds — creating educational centers, building resources for communities — all through the internet.

Joe Kennedy III: I’m struck by that, particularly when we talk about the Third Goal of the Peace Corps. Peace Corps can be leveraged to make an impact in communities overseas. But this also means a Volunteer coming home, engaging in teaching or an after-school program, being able to create a connection with a community the entire world away. We’ve all run into that challenge of somebody saying, “Oh, you just came out of the Peace Corps. How was it?” As if you could sum up the last two years of your life in 20 seconds. This enables us to actually be able to show those connections and tell that story in a much more powerful way. Given your time in Benin, your commitment to the ideals that Peace Corps hopes to help ignite in people, and your future with the U.S. Foreign Service: What does the Peace Corps mean to you?

Marieme Foote: Peace Corps, at its heart — as Bill Josephson said — is about wanting to serve and be with people. The people-to-people connection is the best part of Peace Corps. I still talk to my host family; I hope they’ll be my family forever. It has built some beautiful relationships in my life. Finding new ways to make this experience something all Americans can do, that everyone around the world can partake in and celebrate, is important in bridging connections. How we can make this experience accessible to this new generation — that’s my question going forward.

For All They’ve Done: Recognition and Thanks to Bill Josephson and Bill Moyers

As part of the Mark the Moment celebration, National Peace Corps Association presented Bill Josephson and Bill Moyers with special recognition for their work. In presenting the tokens of recognition, NPCA Board Chair Maricarmen Smith-Martinez noted, “Peace Corps wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for your efforts and the collaboration of others 60 years ago. And the greatest tribute, no doubt, is the impact of the 240,000 Volunteers who have served in every part of the world, an impact that is both immeasurable and unforgettable.”

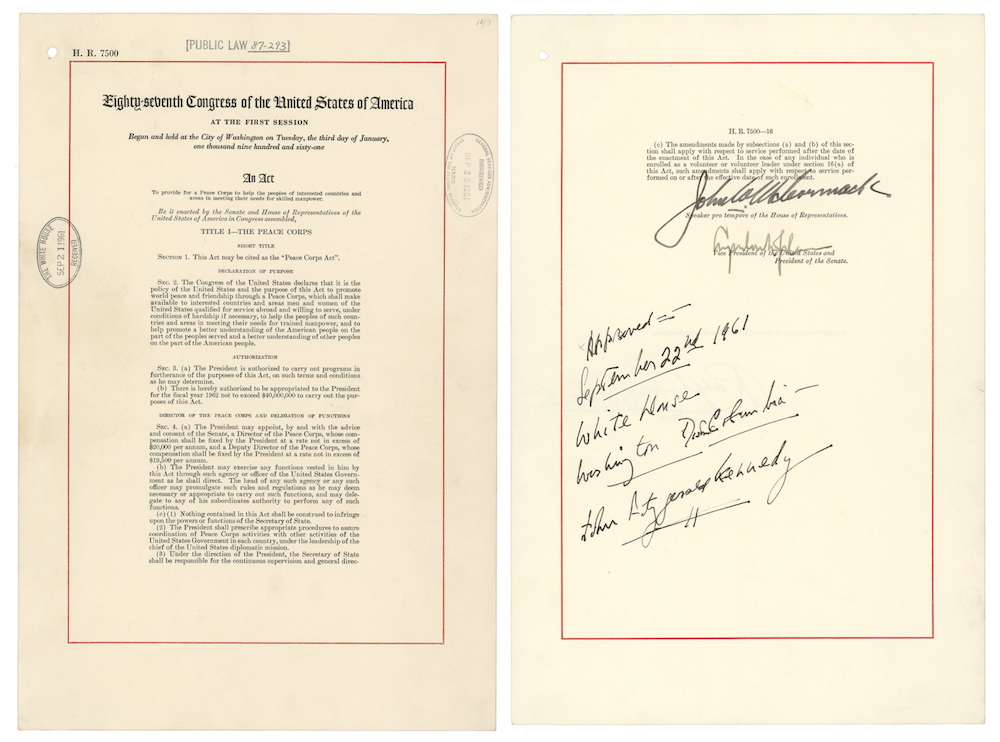

The Peace Corps Act: first page and last, with JFK’s signature. Document courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

NOW LISTEN to this conversation on Spotify.

Story updated December 22, 2021 at 3 PM.